Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

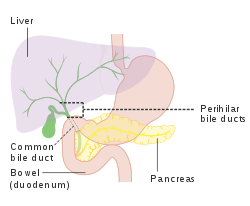

Biliary tract

View on Wikipedia

| Biliary tract | |

|---|---|

Ducts of the biliary tract | |

| Details | |

| Function | Facilitate movement of bile, which aids in fat absorption |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D001659 |

| FMA | 79646 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The biliary tract (also biliary tree or biliary system) refers to the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts, and how they work together to make, store and secrete bile.[1] Bile consists of water, electrolytes, bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids and conjugated bilirubin.[2] Some components are synthesized by hepatocytes (liver cells); the rest are extracted from the blood by the liver.[3]

Bile is secreted by the liver into small ducts that join to form the common hepatic duct.[4] Between meals, secreted bile is stored in the gallbladder.[5] During a meal, the bile is secreted into the duodenum (part of the small intestine) to rid the body of waste stored in the bile as well as aid in the absorption of dietary fats and oils.[5]

Structure

[edit]

2. Intrahepatic bile ducts

3. Left and right hepatic ducts

4. Common hepatic duct

5. Cystic duct

6. Common bile duct

7. Ampulla of Vater

8. Major duodenal papilla

9. Gallbladder

10–11. Right and left lobes of liver

12. Spleen

13. Esophagus

14. Stomach

15. Pancreas:

16. Accessory pancreatic duct

17. Pancreatic duct

18. Small intestine:

19. Duodenum

20. Jejunum

21–22. Right and left kidneys

The front border of the liver has been lifted up (brown arrow).[6]

The biliary tract refers to the path by which bile is secreted by the liver then transported to the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. A structure common to most members of the mammal family, the biliary tract is often referred to as a tree because it begins with many small branches that end in the common bile duct, sometimes referred to as the trunk of the biliary tree. The duct, the branches of the hepatic artery, and the portal vein form the central axis of the portal triad.[7] Bile flows in the direction opposite to that of the blood present in the other two channels.[8]

The system is usually referred to as the biliary tract or system,[9] and can include the use of the term "hepatobiliary" when used to refer just to the liver and bile ducts.[1] The name biliary tract is used to refer to all of the ducts, structures and organs involved in the production, storage and secretion of bile.[10]

The tract is as follows:

- Bile canaliculi >> Canals of Hering >> intrahepatic bile ductule (in portal tracts / triads) >> interlobular bile ducts >> left and right hepatic ducts[4]

- These merge to form the common hepatic duct[4]

- The common hepatic duct exits the liver and joins with the cystic duct from gall bladder[4]

- Together these form the common bile duct which joins the pancreatic duct[4]

- These pass through the ampulla of Vater and enter the duodenum[4]

Function

[edit]Bile is secreted by the liver into small ducts that join to form the common hepatic duct.[2] Between meals, secreted bile is stored in the gall bladder, where 80–90% of the water and electrolytes can be absorbed, leaving the bile acids and cholesterol.[5] During a meal, the smooth muscles in the gallbladder wall contract, causing bile to be secreted into the duodenum to rid the body of waste stored in the bile as well as aid in the absorption of dietary fats and oils by solubilizing them using bile acids.[5]

Clinical significance

[edit]

Gallstones can form within the gallbladder and get stuck within the biliary tract, leading to various diseases depending on the location of the stone.[11] Gallstone disease, or cholelithiasis, is very common in the United States, impacting over 20 million people.[11]

Gallstones frequently occur without causing symptoms– this is known as asymptomatic cholelithiasis.[11] Sometimes gallstones may get stuck in the cystic duct, which serves as a bridge between the gallbladder and the common bile duct, and can lead to inflammation in the wall of the gallbladder.[11] This inflammation of the gallbladder is known as cholecystitis and is a common indication for surgical removal of the gallbladder, or cholecystectomy.[12]

Occasionally gallstones may become lodged in the common bile duct and obstruct the flow of bile from the gallbladder to the small intestine– this condition is known as choledocholithiasis[11] and is another indication for cholecystectomy.[12] The common bile duct, commonly abbreviated CBD, is formed by the union of the cystic duct and common hepatic duct, and it later joins the pancreatic duct to terminate in the Ampulla of Vater at the small intestine. The function of the common bile duct is to allow bile to travel from the gallbladder to the small intestine, mixing with pancreatic digestive enzymes along the way.[4] One possible complication of choledocholithiasis is an infection of the bile ducts between the liver and the gallstone lodged in the common bile duct. This condition is known as acute cholangitis and is commonly associated with a triad of clinical symptoms known as Charcot's Triad, which includes fever, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and jaundice.[11] This constellation of symptoms has a 96% specificity for cholangitis,[11] and can be expanded upon with the addition of hypotension and altered mental status to form Reynold's Pentad.[11]

The biliary tract can also serve as a reservoir for intestinal tract infections. Since the biliary tract is an internal organ, it has no somatic nerve supply, and biliary colic due to infection and inflammation of the biliary tract is not a somatic pain. Rather, pain may be caused by luminal distension, which causes stretching of the wall. This is the same mechanism that causes pain in bowel obstructions.[13]

Chronic inflammatory conditions of the biliary tract, including Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) and Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (PBC), can lead to hardening of the ducts in the biliary tree.[14]

An obstruction of the biliary tract can result in jaundice, a yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dorland WA (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 846. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ a b Hundt, Melanie; Basit, Hajira; John, Savio (2022), "Physiology, Bile Secretion", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29262229, retrieved 2022-11-14

- ^ Townsend C (2022). Sabiston Textbook of Surgery (21st ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1489–1527. ISBN 978-0-275-97283-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vakili, Khashayar; Pomfret, Elizabeth A. (December 2008). "Biliary anatomy and embryology". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 88 (6): 1159–1174, vii. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2008.07.001. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 18992589.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Mark W.; Small, Kaitlynn; Kashyap, Sarang; Deppen, Jeffrey G. (2022), "Physiology, Gallbladder", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29494095, retrieved 2022-11-03

- ^ Standring S, Borley NR, eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice. Brown JL, Moore LA (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 1163, 1177, 1185–6. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- ^ Jurkovich, G. J.; Hoyt, D. B.; Moore, F. A.; Ney, A. L.; Morris, J. A.; Scalea, T. M.; Pachter, H. L.; Davis, J. W. (September 1995). "Portal triad injuries". The Journal of Trauma. 39 (3): 426–434. doi:10.1097/00005373-199509000-00005. ISSN 0022-5282. PMID 7473903.

- ^ Wolkoff, Allan W.; Cohen, David E. (February 2003). "Bile acid regulation of hepatic physiology: I. Hepatocyte transport of bile acids". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 284 (2): G175–179. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00409.2002. ISSN 0193-1857. PMID 12529265.

- ^ Biliary+tract at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Dorland WA (2012). Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (32nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 1946. ISBN 978-1-4160-6257-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lam, Robert; Zakko, Alan; Petrov, Jessica C.; Kumar, Priyanka; Duffy, Andrew J.; Muniraj, Thiruvengadam (July 2021). "Gallbladder Disorders: A Comprehensive Review". Disease-a-Month. 67 (7) 101130. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2021.101130. ISSN 1557-8194. PMID 33478678.

- ^ a b Hassler, Kenneth R.; Collins, Jason T.; Philip, Ken; Jones, Mark W. (2022), "Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28846328, retrieved 2022-11-03

- ^ Lin YM, Fu Y, Wu CC, Xu GY, Huang LY, Shi XZ (March 2015). "Colon distention induces persistent visceral hypersensitivity by mechanotranscription of pain mediators in colonic smooth muscle cells". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 308 (5): G434 – G441. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00328.2014. PMC 4346753. PMID 25540231.

- ^ Franco, J.; Saeian, K. (April 1999). "Biliary tract inflammatory disorders: primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 1 (2): 95–101. doi:10.1007/s11894-996-0006-8. ISSN 1522-8037. PMID 10980934.

- ^ "Definition: biliary tract". Online Medical Dictionary.