Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

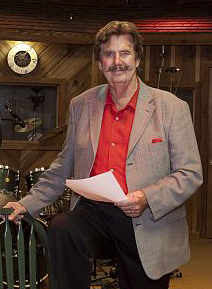

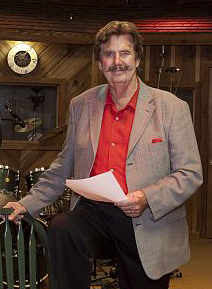

Rick Hall

View on Wikipedia

Roe Erister "Rick" Hall[1] (January 31, 1932 – January 2, 2018)[2] was an American record producer, songwriter, and musician who became known as the owner of FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. As the "Father of Muscle Shoals Music", he was influential in recording and promoting both country and soul music, and in helping develop the careers of such musicians as Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, Duane Allman and Etta James.

Key Information

Hall was inducted into the Alabama Music Hall of Fame in 1985 and also received the John Herbert Orr Pioneer Award.[3] In 2014, he won the Grammy Trustees Award in recognition of his lengthy career. Hall remained active in the music industry with FAME Studios, FAME Records, and FAME Publishing.[4]

Early life

[edit]Hall was born into a family of sharecroppers in Forest Grove, Tishomingo County, Mississippi to Herman Hall,[2] a sawmill worker and sharecropper[5] and his wife, Dollie Dimple Daily Hall; he had one sister.

After his mother left home when young Hall was aged 4,[2] he and his sister were raised in rural poverty[5] by his father and grandparents in Franklin County, Alabama.[2][6] According to The Guardian, and confirmed by Hall himself in the 2013 documentary Muscle Shoals, Dollie worked in a bordello after leaving the family. His father was a gospel music fan and his uncle gave Rick a mandolin at age 6. Later, he learned to play guitar.[7]

Hall moved to Rockford, Illinois as a teenager, working as an apprentice toolmaker, and began playing in local bar bands.[8] When he was drafted for the Korean War, he declared himself a conscientious objector, joined the honor guard of the Fourth United States Army, and played in a band that also included Faron Young and the fiddler Gordon Terry.[8]

Early career as musician and songwriter

[edit]When Hall returned to Alabama he resumed factory life, working for Reynolds Aluminum in Florence.[8] When both his new bride Faye and his father died within a two-week period in 1957, he suffered depression and began drinking regularly.[7] He later began moving around the area playing guitar, mandolin, and fiddle with a local group, Carmol Taylor and the Country Pals, and first met saxophonist Billy Sherrill.[8] The group appeared on a weekly regional radio show at WERH in Hamilton.[8] Subsequently, Hall formed a new R&B group, the Fairlanes, with Billy Sherrill, fronted by the singer Dan Penn, with Hall playing bass.[8] He also began writing songs at that time.[9][8]

Hall left the Fairlanes to concentrate on becoming a songwriter and record producer.[10] He had his first songwriting successes in the late 1950s, when George Jones recorded his song "Achin', Breakin' Heart", Brenda Lee recorded "She'll Never Know", and Roy Orbison recorded "Sweet and Innocent".[6] In 1960, he started a company based in Florence, Alabama, together with fellow ex-Fairlanes member Billy Sherrill, the future producer of Tammy Wynette's records. They named their company FAME (Florence Alabama Music Enterprises) and opened their first primitive studio above a drugstore.[7]

Producer Sam Phillips, originally from Florence, Alabama, was an early mentor. During a 2015 interview with The New York Times, Hall recalled those early days. "We would sit up and talk until 2 o'clock in the morning and Sam would tell me, 'Rick, don't go to Nashville, because they'll eat your soul alive.' I wanted to be like Sam — I wanted to be somebody special."[2]

Success with FAME Studios

[edit]In 1959, Hall and Sherrill accepted an offer from Tom Stafford, the owner of a recording studio, to help set up a new music publishing company in the town of Florence, to be known as Florence Alabama Music Enterprises, or FAME.[11] However, in 1960, Sherrill and Stafford dissolved the partnership, leaving Hall with rights to the studio name.

Hall's first success as a producer in a small studio was with one of his first recordings, Arthur Alexander's "You Better Move On" in 1961.[6] The commercial success of the record gave Hall the financial resources to establish a new, larger FAME recording studio[12] on Avalon Avenue in Muscle Shoals.[6][8][12][7] That song became the first gold record in the history of Muscle Shoals; at the time, Hall had licensed it to Dot Records. The song was recorded by others too, including the Rolling Stones in 1964.[13] In that era, his musicians included Norbert Putnam, David Briggs, Peanut Montgomery and Jerry Carrigan.[12]

Though Hall grew up in a culture dominated by country music, he had a love of R&B music and, in the highly segregated state of Alabama, regularly flouted local policies and recorded many black musicians.[2] Hall wrote: "Black music helped broaden my musical horizons and open my eyes and ears to the widespread appeal of the so-called 'race' music that later became known as 'rhythm and blues".[2] Hall's successes continued after the Atlanta-based agent Bill Lowery brought him acts to record, and the studio produced hits for Tommy Roe, Joe Tex, the Tams, and Jimmy Hughes.[8] However, in 1964, Hall's regular session group — David Briggs, Norbert Putnam, Jerry Carrigan, Earl "Peanut" Montgomery, and Donnie Fritts — became frustrated at being paid minimum union-scale wages by Hall, and left Muscle Shoals to set up a studio of their own in Nashville, Tennessee.[8] Hall then assembled a new studio band, including Spooner Oldham, Jimmy Johnson, David Hood, and Roger Hawkins, and continued to produce hit records.[8]

Hall's FAME studio prospered. "By the mid-'60s it had become a hotbed for pop musicians of various stripes, including the Rolling Stones, Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Clarence Carter, Solomon Burke and Percy Sledge," according to the Los Angeles Times. Singer Aretha Franklin credited Hall for the "turning point" in her career in the mid 1960s, taking her from a struggling artist to the "Queen of Soul".[14] According to Hall, one of the reasons for FAME's success at a time of stiff competition from studios in other cities was that he overlooked the issue of race, a perspective he called "colorblind".[2] "It was a dangerous time, but the studio was a safe haven where blacks and whites could work together in musical harmony," Hall wrote in his autobiography.[5] Decades later, a publication in Malaysia referred to Hall as a "white fiddler who became an unlikely force in soul music".[15]

In 1966, he helped license Percy Sledge's "When a Man Loves a Woman", produced by Quin Ivy, to Atlantic Records, which then led to a regular arrangement under which Atlantic would send musicians to Hall's Muscle Shoals studio to record.[16] The studio produced further hit records for Wilson Pickett, James & Bobby Purify, Aretha Franklin, Clarence Carter, Otis Redding, and Arthur Conley, enhancing Hall's reputation as a white Southern producer who could produce and engineer hits for black Southern soul singers.[6][8] He produced many sessions using guitarist Duane Allman.[10] He also produced recordings for other artists, including Etta James, whom he persuaded to record Clarence Carter's song "Tell Mama".[2] However, his fiery temperament led to the end of the relationship with Atlantic after he got into a fistfight with Aretha Franklin's husband, Ted White, in late 1967.[8]

In 1969, FAME Records, with artists including Candi Staton, Clarence Carter and Arthur Conley, established a distribution deal with Capitol Records.[12] Hall then turned his attention away from soul music towards mainstream pop, producing hits for the Osmonds, Paul Anka, Tom Jones, and the Osmond family.[6] Also in 1969, another FAME Studio house band, Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, affectionately called The Swampers, consisting of Barry Beckett (keyboards), Roger Hawkins (drums), Jimmy Johnson (guitar), and David Hood (bass), left the FAME studio to found the competing Muscle Shoals Sound Studio at 3614 Jackson Highway in Sheffield, with start-up funding from Jerry Wexler.[17][18][19] Subsequently, Hall hired the Fame Gang as the new studio band.[20]

FAME Records was independent in 1962–1963. Hall signed a distribution deal with Vee-Jay from October 1963-June 1965. He moved his label to Atlantic distribution November 1965–September 1967. In May 1969 to May 1971, the label was distributed by Capitol, and finally, to United Artists from May 1972 until approximately April 1974.

The studio continued to do well through the 1970s[20] and Hall was able to convince Capitol Records to distribute FAME recordings.[13] In 1971, he was named Producer of the Year by Billboard magazine,[8] a year after having been nominated for a Grammy Award in the same category.[21] In the same year, Mac Davis recorded the first of his 12 albums at the FAME studio; four of the songs later received gold and platinum records.[12]

Through the 1970s, Hall continued moving back towards country music, producing hits for Mac Davis, Bobbie Gentry, Jerry Reed, and the Gatlin Brothers, as well as returning to work for the Osmonds as they moved to country.[13][8] He also worked with the songwriter and producer Robert Byrne to help a local bar band, Shenandoah, top the national Hot Country Songs chart several times in the 1980s and 1990s.[6] Hall's publishing staff of in-house songwriters wrote some of the biggest country hits in those decades. His publishing catalog included "I Swear" written by Frank Myers and Gary Baker.[6][12] In 1985 he was inducted into the Alabama Music Hall of Fame, his citation referring to him as the "Father of Muscle Shoals Music."[6]

In 2007, Hall reactivated the FAME Records label through a distribution deal with EMI.[22]

Artists who recorded at FAME in subsequent years include Gregg Allman who recorded the Southern Blood LP, Drive-By Truckers, Jason Isbell, Tim McGraw with his hit "I Like It, I Love It", the Dixie Chicks, George Strait, Martina McBride, Kenny Chesney and others.[13]

Later life

[edit]Some years after the death of his first wife, he met and married Linda Cross of Leighton, Alabama. The couple had three sons, Rick Jr., Mark, and Rodney. Hall had five grandchildren, who affectionately called him Pepaw. Hall's life and career are profiled in the 2013 documentary film Muscle Shoals.[23] During an interview before the release of the movie, Hall told a journalist that in 2009, he and his wife had donated their home of 30 years to the Boys and Girls Ranches of Alabama, a charity for abused and neglected children. The house now serves as a home to up to seventeen teenage girls at a time that have been removed from their families through no fault of their own.

In 2014, Hall was awarded the Grammy Trustees Award for his significant contribution to the field of recording.[24][25]

Hall published his memoirs in a book titled The Man from Muscle Shoals: My Journey from Shame to Fame in 2015.[9][10] On December 17, 2016, Hall was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of North Alabama in Florence.[26]

He died on January 2, 2018, aged 85, at his home in Muscle Shoals, after a battle with prostate cancer.[23][27]

Legacy

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

In its obituary, The New Yorker concluded its coverage of Hall's career with this comment: "Muscle Shoals remains remarkable not just for the music made there but for its unlikeliness as an epicenter of anything; that a tiny town in a quiet corner of Alabama became a hotbed of progressive, integrated rhythm and blues still feels inexplicable. Whatever Hall conjured there—whatever he dreamt, and made real—is essential to any recounting of American ingenuity. It is a testament to a certain kind of hope."[28] An Alabama publication commented that Hall is survived by his family "and a Muscle Shoals music legacy like no other".[29] An editorial in the Anniston Star (Alabama) concludes with this epitaph, "If the world wants to know about Alabama — a state seldom publicized for anything but college football and embarrassing politics — the late Rick Hall and his legacy are worthy models to uphold".[30]

Aretha Franklin recorded her hit "I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)" at FAME in 1967, with the "Swampers" providing the accompaniment.[31] She later publicly acknowledged Rick Hall "for the 'turning point'" in her career, taking her from a struggling artist" to a major music star.[32]

In early 2018, Rolling Stone published a retrospective of Hall's career and included this evaluation. "Hall's Grammy-winning production touched nearly every genre of popular music from country to R&B, and his Fame Studio and publishing company were a breeding ground for future legends in the worlds of songwriting and session work, as well as a recording home to some of the greatest musicians and recording artists of all time."[13]

The UK newspaper The Guardian summarized Hall's career with these words: "What made Hall ... stand out was his position at the confluence of the three key strands of black and white American popular music – gospel, country and R&B – which merged to provide the foundation of so much of significance in that and succeeding decades."[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "Pink high heel shoes (and the blues) w & m Rick Hall (Roe Erister Hall), Dan Penn, pseud. of Dan Pennington, & Tom H. Stafford". Faqs.org. Archived from the original on March 28, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lewis, Randy (January 2, 2018). "Rick Hall, the father of the Muscle Shoals sound, dies at 85". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Rick Hall – Tishomingo, Alabama". Alabama Music Hall of Fame. 1985. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

Recognized as the 'Father of Muscle Shoals Music,' maverick producer, publisher, songwriter, musician and studio owner Rick Hall founded FAME Recording Studios and produced the Muscle Shoals music industry's first national hits.

- ^ "Publishing". FAME. 2017. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

Today the company has a catalog of over 3,000 songs with multiple top 10 singles, ASCAP awards and Song of the Year awards.

- ^ a b c Pareles, Jon (January 3, 2018). "Rick Hall, Music Producer Known for Muscle Shoals Sound, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Rick Hall – Tishomingo, Alabama". Alabama Music Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Richard (January 3, 2018). "Rick Hall obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Kurutz, Steve. Rick Hall at AllMusic

- ^ a b Herr, John (July 29, 2015). "Meet Rick Hall: Founder of Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals". Alabama NewsCenter. Alabama Power. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c Carrigan, Henry (May 2015). "Talking with Rick Hall: 'The Man from Muscle Shoals'". No Depression. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "Rick Hall – Tishomingo, Alabama". Alabama Music Hall of Fame. 1985. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

FAME Recording Studio's name is actually an acronym for 'Florence Alabama Music Enterprises.'

- ^ a b c d e f "Our History". FAME. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Producer Rick Hall, 'Father of Muscle Shoals Music,' Dead at 85". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "Rick Hall, the father of the Muscle Shoals sound, dies at 85". HeraldNet.com. January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Samad, Joe (January 4, 2018). "Unlikely producer of soul sound Rick Hall dies at 85". The Malaysian Insight. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "Quin Ivy - Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Westergaard, Sean (2017). "Artist Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

often affectionately called "the Swampers" are widely regarded as one of the most important American recording studio "house bands" emerging in the golden age of rock and soul.

- ^ Simons, Dave (January 30, 2009). "Tales From the Top: The Rolling Stones' Sticky Fingers". Broadcast Music, Inc. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "HISTORY - It's In The Water". MS Musicfoundation. 2017. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

In 1969 Rick Hall's house band, the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, left FAME and partnered with Jerry Wexler to found the Muscle Shoals Sound studio at 3614 Jackson Highway in Sheffield.

- ^ a b Brown, Mick (October 2013). "How Muscle Shoals became music's most unlikely hit factory". The Daily Telegraph. London, England. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "BMI Mourns the Loss of Muscle Shoals Legend Rick Hall". Broadcast Music, Inc. January 2, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "Rick Hall – Tishomingo, Alabama". Alabama Music Hall of Fame. 1985. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

deal with EMI ... combined new material by FAME artists with reissues of classic recordings from Muscle Shoals' Southern soul heyday..

- ^ a b Russ Corey (January 2, 2018). "Shoals music pioneer Rick Hall dies at 85". Timesdaily.com. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ "Trustees Award: Rick Hall". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. January 21, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (January 26, 2014). "Shoals sound legacy: Rick Hall earns Grammy Trustee Award from Recording Academy". Timesdaily.com. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ "University of North Alabama Announces Honorary Degree for Music Icon Rick Hall". University of North Alabama. July 25, 2016. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Jarrett, Amanda (January 2, 2018). ""Father of Muscle Shoals Music" dead at 85". WAFF. Retrieved January 2, 2018.

- ^ Petrusich, Amanda (January 3, 2018). "Remembering Rick Hall and the Musical Alchemy of FAME Studios". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "The musical secrets of FAME Studios legend Rick Hall". AL.com. January 4, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ "Editorial: The genius of a music legend". The Anniston Star. January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Taylor, David (August 19, 2018). "The day Aretha Franklin found her sound – and a bunch of men nearly killed it". The Guardian. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

Atlantic picked her up and in early 1967 sent her to FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals.

- ^ "Early History". Big River Broadcasting. Retrieved April 16, 2021.