Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Johannes de Sacrobosco

View on Wikipedia

Johannes de Sacrobosco, also written Ioannes de Sacro Bosco, later called John of Holywood or John of Holybush (c. 1195 – c. 1256), was a scholar, Catholic monk, and astronomer who taught at the University of Paris.

He wrote a short introduction to the Hindu-Arabic numeral system. Judging from the number of manuscript copies that survive today, for the next 400 years it became the most widely read book on that subject.[1][2] He also wrote a short textbook which was widely read and influential in Europe during the later medieval centuries as an introduction to astronomy. In his longest book, on the computation of the date of Easter, Sacrobosco correctly described the defects of the then-used Julian calendar, and recommended a solution similar to the modern Gregorian calendar three centuries before its implementation.[1]

Very little is known about the education and biography of Sacrobosco. For one thing, his year of death has been guessed at 1236, 1244, and 1256, each of which is plausible and each lacking adequate evidence.[1]

Place of birth

[edit]The country in which he was born is uncertain. Robertus Anglicus wrote in 1271 that Sacrobosco was born in England.[3] That could be true, yet there is neither good supporting nor good contradicting evidence for it. Based on Anglicus writing so soon after Sacrobosco's death, a birthplace in England may deserve greater credence than later suggestions.

Among those other possibilities, several different tenuous efforts have been made to figure out his birthplace from his appellative name de Sacrobosco. Long after his death, Johannes de Sacrobosco was called and sometimes is still called by the name "John of Holywood" or "John of Holybush", a name which was constructed by post-hoc reverse translation of the Medieval Latin sacer boscus, "holy (sacred) wood". Sacer Boscus or Romance Sacro Bosco as such is an unknown town or region. One traditional report, that he was born in Halifax, West Yorkshire, is the speculation of a 16th-century antiquary, John Leland,[1]: 176–177 which was discredited by William Camden: Halifax[4] means "holy hair", not "holy wood".[1]: 177

Thomas Dempster identified Sacrobosco with an Augustinian canon from Holywood Abbey, Nithsdale,[a] which would be a reason for supposing him to have been born in Scotland.[1][5] The historian John Veitch claimed that he was born in Galloway and studied the classics among the monks of Whithorn and Dryburgh.[6]

Based on a suggestion by Stanihurst, Holywood, County Down also claims Sacrobosco. However, Pedersen attributes this assertion to Holywood being familiar to Stanihurst. A similar claim is made that he was born in Holywood, County Wicklow, but there is no known supporting historical document.

Pedersen mentioned that James Ware, writing in 1639, believed that the birthplace of Sacrobosco was near Dublin.[1] Stanihurst and even Pedersen were probably unaware that the seat of the Sacrobosco / Hollywood family in Ireland was in Artane, a suburb of Dublin.[7] Local historical records in Ireland seem to indicate that Johannes de Sacrobosco was a member of the Hollywood family, born in Artane Castle.[8][1]: 177–178

Life

[edit]The story that he was educated at the University of Oxford is no better documented than the stories on his place of birth.[1]: 177

According to a seventeenth-century account, he arrived at the University of Paris on 5 June 1221, but whether as a student or as a graduate (licentiate – one already having a Master of Arts degree from another university, and thus qualified to teach) is unclear.[1]: 175–182 In due course, he began to teach the mathematical disciplines at the University of Paris.

The year of his death is uncertain, with evidence supporting the years 1234, 1236, 1244, and 1256.[1]: 186–189, 192 The inscription marking his burial place in the monastery of Saint-Mathurin, Paris, described him as a "computist" – one who was an expert on calculating the date of Easter.[1]: 181

- De Sacrobosco qui computista Joannes

- tempora discrevit, iacet hic a tempore raptus.

- Tempora qui sequeris, memor esto quod morieris.

- Si miser es, plora: miserans pro me procor ora.

On 14 May 2021, asteroid 14541 Sacrobosco, discovered by Czech astronomers Jana Tichá and Miloš Tichý in 1997, was named in his memory.[9]

Tractatus de Sphaera

[edit]

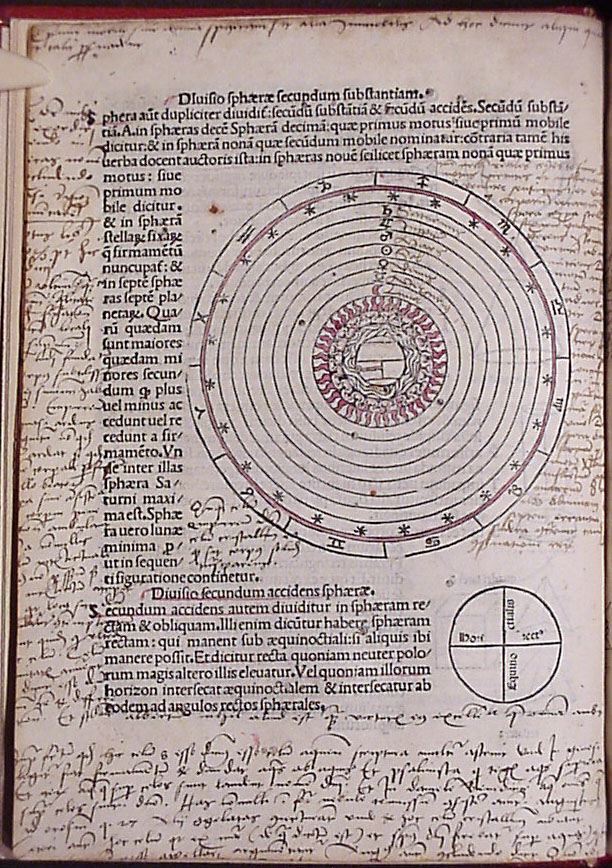

About 1230, his best-known work, Tractatus de Sphaera / De Sphaera Mundi (Treatise on the Sphere / On the Sphere of the World) was published. In this book, Sacrobosco gives a readable account of the Ptolemaic universe. Ptolemy's (updated) Almagest had been translated into Latin in 1175 by Gerard of Cremona from the Arabic translation held in Toledo and copies had quickly found their way to Paris. In addition Sacrobosco was able to draw on translations of the Arabic astronomers Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Biruni, al-Urdi, and al-Fargani.[10]

The "sphere" Sacrobosco was referring to is the celestial sphere – an imaginary backdrop of the stars in the sky – which was the meaning of the word mundi ("world") at that time, not the planet Earth. Though principally about astronomy, in its first chapter the book also contains a clear description of the Earth as a sphere. De Sphaera Mundi was required reading by students in all western European universities for the next four hundred years.

Algorismus

[edit]Sacrobosco's Algorismus a.k.a. De Arte Numerandi is thought to have been his first work, written c. 1225. The Hindu–Arabic methods of numerical calculation had arrived in Latin Europe during the previous fifty years but had not been disseminated on a wide scale. Sacrobosco's Algorismus was the first text to introduce Hindu–Arabic numerals and arithmetical procedures into the European university curriculum.[2][1]: 199–200

De Anni Ratione

[edit]Sacrobosco may now be most famous for his criticism of the Julian calendar. In his c. 1235 book on computation of Easter's date, De Anni Ratione [On Reckoning Years], he maintained that the calendar had accumulated an error of 10 days and that some correction was needed.

The Julian calendar was instituted in the 1st century BCE. The Julian calendar year contained 365.25 days, with the 0.25 day provided for by a Leap year once every fourth year. However, the more precise length of a solar year is about 365.2422 days. By the 13th century, the less accurate 365.25 days had resulted in an accumulated error of about 10 days in the date of the vernal equinox. Sacrobosco made no proposal on how to get rid of the accumulated error. But looking to the future, he proposed to leave one day out of the calendar every 288 years to prevent further error.[1]: 209–210 [b] His criticism would foreshadow the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1582, which corrected the error observed by Sacrobosco by skipping 10 days, and dropping three of the century leap years in every 400-year period.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Holywood Abbey, Nithsdale was a house of the Premonstratensian order.

- ^ The data Sacrobosco used were not quite as accurate as the Alfonsine tables based on the Arabic Tables of Toledo, which were published in Latin in the 1270s, a few decades after Sacrobosco. The astronomer Campanus of Novara did similar work in 1268, again using Arabic astronomical sources. Sacrobosco also was influenced by Arabic astronomy, but not the same sources, and there is no indication in his writings that he could read Arabic.

Bibliography

[edit]- de Sacrobosco, Johannes (1472) [c. 1230]. Tractatus de Sphæra [Treatise on the Sphere]. Ferrara. (translation) (see article under alt. title: De Sphaera Mundi)

- de Sacrobosco, Johannes (1523) [c. 1490, 1517, 1521–1522]. Algorismus or De Arte Numerandi [Algorithms or On the Art of Numbers] (in Latin). Vienna; Cracow; Venice: Hieronymus Vietor & var. – via wikisource.org. printed without date or place [1490?], and at Vienna, 1517, by Hieronymus Vietor; Cracow, 1521 or 1522; and Venice, 1523

- de Sacrobosco, Johannes (1572) [c. 1538; 1550]. De Anni Ratione or De Computo Ecclesiastico [On the Reckoning of Years or On Ecclesiastical Computation]. Paris. octavo.

- Sacrobosco, Ioannes : de (1518). Sphaera mundi (in Latin). Venezia: Lucantonio Giunta (1.).

- Sacrobosco, Ioannes : de (1531). Sphaera mundi (in Latin). Venezia: Lucantonio Giunta (1.).

- Sacrobosco, Ioannes : de (1531). De sphaera (in Latin). Venezia: Lucantonio Giunta (1.).

- Sacrobosco, Ioannes : de (1561). Sphaera mundi (in Latin). Paris: Guillaume Cavellat.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Pedersen, Olaf (1985). "In Quest of Sacrobosco". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 16 (3): 175–221. Bibcode:1985JHA....16..175P. doi:10.1177/002182868501600302. S2CID 118227787.

- ^ a b Smith, D.E.; Karpinski, L.C. (1911). "The spread of the [Hindu–Arabic] numerals in Europe". The Hindu–Arabic Numerals. pp. 58–59, 134–135 – via archive.org.

- ^ "Johannes de Sacrobosco" (biography). University of Cambridge.

- ^ Müller, Adolf (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8.

- ^ "Johannes de Sacrobosco" (biography). University of St. Andrews.

- ^ Veitch, John (1893), History and Poetry of the Scottish Border, Volume 1, William Blackwood and Sons, p. 341

- ^ D'Alton, John (1838). The History of the County of Dublin.

- ^ "Parish of Holywood". Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ^ "WGSBN Bulletin Archive". Working Group Small Body Nomenclature. 14 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021. (Bulletin #1)

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1991). Inventing the Flat Earth. Praeger. p. 19[note]. ISBN 978-0-275-93956-4 – via archive.org.

Sources

[edit]- . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

- High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Johannes de Sacrobosco. History of Science Collections (.jpg and .tiff images). Online Galleries. University of Oklahoma Libraries. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- de Sacro Bosco, Johannes (1841). Tractatus de Arte Numerandi [Treatise on the Art of Numbers] (in Latin) – via archive.org.

- de Sacro Bosco, Johannes. De Anni Ratione [On the Reckoning of Years] (in Dutch).