Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

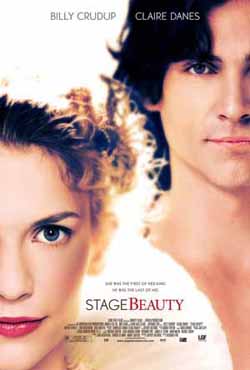

Stage Beauty

View on Wikipedia

| Stage Beauty | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Eyre |

| Screenplay by | Jeffrey Hatcher |

| Based on | "Compleat Female Stage Beauty" by Jeffrey Hatcher |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Andrew Dunn |

| Edited by | Tariq Anwar |

| Music by | George Fenton |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2.2 million |

Stage Beauty is a 2004 romantic period drama directed by Richard Eyre. The screenplay by Jeffrey Hatcher is based on his play Compleat Female Stage Beauty, which was inspired by references to 17th-century actor Edward Kynaston made in the detailed private diary kept by Samuel Pepys.

Plot

[edit]Ned Kynaston is one of the leading actors of his day, particularly famous for his portrayal of female characters, predominantly Desdemona in Othello. His dresser, Maria, aspires to perform in the legitimate theatre but is forbidden because of a law, at that time in effect, forbidding theatres to employ actresses. Instead, she appears in productions at a local tavern under the pseudonym Margaret Hughes. Her popularity is aided by the novelty of a woman acting in public, which attracts the attention of Sir Charles Sedley, who offers his patronage. Eventually, she is presented to Charles II.

Nell Gwynn, an aspiring actress and Charles II's mistress, comes upon Kynaston ranting about women on stage and seduces Charles II into banning men from playing female roles.[2] Kynaston, having gone through a long and strenuous training to play female roles, finds himself without a guise by which to keep the attention of his lover, George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, as the latter never had intentions to lead a homosexual life and Kynaston has lost the acceptance of London society which had started to circulate rumors about their association. He is reduced to performing bawdy songs in drag in music halls, while Maria's career thrives, although her ability to emulate Kynaston falls short because, as she says, Kynaston never fights as a woman would do.

Called upon for a royal performance, Maria panics and her friends implore Kynaston for coaching, during which she coaches him to develop his ability to regain a theatrical career in male roles. He agrees, with the proviso that he replace the company head Thomas Betterton in the role of Othello. Maria becomes a theatrical star.

Cast

[edit]- Billy Crudup as Ned Kynaston

- Claire Danes as Maria / Margaret Hughes

- Tom Wilkinson as Thomas Betterton

- Rupert Everett as King Charles II

- Zoë Tapper as Nell Gwynn

- Richard Griffiths as Sir Charles Sedley

- Hugh Bonneville as Samuel Pepys

- Ben Chaplin as George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

- Edward Fox as Sir Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon

- Alice Eve as Miss Frayne

- Stephen Marcus as Thomas Cockerell

- Tom Hollander as Sir Peter Lely

- Fenella Woolgar as Lady Aurelia Meresvale

Production

[edit]While the film is rooted in historical fact – the first English theatre actress, although her name is unknown, is believed to have performed the role of Desdemona[3] – some liberties with the truth were taken. Nell Gwynne is represented as a mistress of the King who subsequently becomes an actress, but in reality she already was a noted theatre personality and actress when Charles II met her. The sequence in which Maria and Kynaston discover naturalistic acting is anachronistic, as naturalism was not developed until the 19th century.

Interiors were filmed at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich and Shepperton Studios in Surrey. According to commentary by production designer Jim Clay on the DVD release of the film, because so little English Restoration architecture remains in London, and documentation of the period is minimal, he was required to use his imagination in creating buildings and back alleys on sound stages.

In the DVD commentary, several cast members recall the film was shot during the hottest UK summer on record (2003), and the temperature under the lights usually hovered at 46 °C (115 °F), making performing in the heavy, layered costumes a grueling experience.

The Costumes were designed by Tim Hatley. Twelve costume houses were involved in the production, including The Royal Shakespeare Company, The National Theater, and Angels & Bermans, as well as the Italian houses Sartoria Farani, Tirelli, Costumi d'Arte, E. Rancati, G.P. 11, and Pompei.

The film premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in May 2004 prior to its general release in the UK. It was shown at the Deauville Film Festival, the Toronto International Film Festival, and the Dinard Festival of British Cinema in France before opening in New York City.

Release

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 64% based on 128 reviews, with a weighted average of 6.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Uneven but enjoyable, Stage Beauty uses historical events as the springboard for a well-acted romance with a charming Shakespearean spin."[4] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 64 out of 100, based on 38 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[5]

In his review in The New York Times, A. O. Scott said, "At times, the movie feels like a fancy-dress version of A Star Is Born ... Mr. Crudup's fine features, which flicker between masculine and feminine as the lighting changes and the mood shifts, are well suited for the role, though his sinewy, birdlike frame suggests Hollywood anorexia more than Restoration curviness ... Stage Beauty is both timorous and ungainly, words that might also describe Ms. Danes's performance. Trapped in an English accent and in a character who must appear conniving and warmhearted in turn, she veers from teariness to brisk indignation like an Emma Thompson doll with a jammed switch. The British actors in smaller roles handle the material better ... George Fenton's Sunday-brunch score, on the other hand, is an indigestible dose of good taste ladled heavily over even the film's witty and delicate moments."[6]

David Rooney of Variety called the film "an intelligent and entertaining adaptation ... skillfully acted, handsomely crafted" and added, "Eyre's spry direction of the refreshingly literate, witty drama shows a pleasingly light touch and a genuine feel for the bustle, backbiting and rivalry of the theater milieu ... In a delicately measured performance that favors graceful subtlety over campy mannerism, Crudup conveys a nuanced sense of a man struggling to know himself ... Put in the unenviable position of playing second fiddle to her male co-star in terms of feminine allure, Danes is lovely nonetheless ... George Fenton's rich orchestral score enlivens the action with an occasional rousing Celtic flavor."[7]

In Rolling Stone, Peter Travers rated the film three out of a possible four stars and called it "bawdy fun ... the gender role-playing puts spine in this period piece that is vital to the here and now."[8]

Carla Meyer of the San Francisco Chronicle said, "The film rarely matches Crudup's performance, appearing confused itself about whether it's farce or drama. But its palette of burnished browns and reds pleases the eye, and at its best, Stage Beauty captures the tensions and electricity of backstage dramas."[9]

In The New Yorker, David Denby observed, "Second-rate bawdiness—that is, bawdiness without the wit of Boccaccio or Shakespeare or even Tom Stoppard—is more infantile than funny, and I'm not sure that the American playwright Jeffrey Hatcher, who concocted this piece for the stage and then adapted it into a movie, is even second-rate. Stage Beauty might be called the spawn of Shakespeare in Love, and, unfortunately, this is a Shakespeare that lacks the graceful spirit and breathless narrative drive of its progenitor."[10]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly rated the film C+ and described it as "an odd amalgam of high spirits, lively ambition, and botched execution."[11]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The film won the Cambridge Film Festival Audience Award for Best Film, was cited by the National Board of Review for Excellence in Filmmaking, and was named the Overlooked Film of the Year by the Phoenix Film Critics Society.

References

[edit]- ^ "Film #22074: Stage Beauty". Lumiere. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ In actuality, it was not that men were banned but that women were allowed on stage. "Women as actresses" (PDF). Notes and Queries. The New York Times. 18 October 1885. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-14. "There seems no doubt that actresses did not perform on the stage till the Restoration, in the earliest years of which Pepys says for the first time he saw an actress upon the stage. Charles II must have brought the usage from the Continent, where women had long been employed instead of boys or youths in the representation of female characters."

- ^ "English Renaissance and Restoration Theatre" by Peter Thomson, The Oxford Illustrated Guide to Theatre, edited by John Rusell Brown, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 206–207.

- ^ "Stage Beauty (2019)". Rotten Tomatoes. 8 October 2004. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "Stage Beauty Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 22 September 2024. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (8 October 2004). "Upstaged by the King, an Actor in Drag Straightens Out". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 September 2024. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Rooney, David (9 May 2004). "Stage Beauty". Variety. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Travers, Peter (6 October 2004). "Stage Beauty". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Meyer, Carla (15 October 2004). "Crudup outshines 'Beauty'". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Denby, David (11 October 2004). "Playing Parts". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (6 October 2004). "Stage Beauty (2004)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 23 January 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

External links

[edit]Stage Beauty

View on GrokipediaOverview

Plot Summary

Stage Beauty is set in 1660s London amid the Restoration theater scene, where male actors traditionally portrayed female characters. The protagonist, Edward "Ned" Kynaston, is a celebrated performer renowned for his interpretation of Desdemona in Shakespeare's Othello.[1] His dresser, Maria, harbors ambitions to act and covertly rehearses female roles, eventually performing Desdemona at a private gathering attended by King Charles II.[8] Struck by her portrayal, the King promulgates a decree prohibiting men from playing women on stage, thereby upending the conventions and catapulting Maria into the spotlight while devastating Ned's career.[8] Maria inherits the role of Desdemona but falters in her debut, eliciting audience mockery for her stiff delivery.[9] Reduced to destitution, Ned performs female impersonations in seedy taverns for meager earnings and becomes ensnared in intrigues with the Duke of Buckingham, who maneuvers for control over theatrical appointments.[10] To hone her skills, Maria approaches Ned for instruction in authentic feminine expression, forging an intricate bond marked by rivalry and mutual dependence.[6] Ned confronts his faltering identity, experimenting with male characters and revealing untapped prowess, such as in an audition for Othello.[9] The duo's collaboration evolves amid personal reckonings, leading to Ned's reclamation of the stage in a masculine guise and prompting the King to reassess rigid gender edicts in performance.[8]

Core Themes

Stage Beauty examines the performativity of gender through the lens of Restoration-era theatre, where male actors like Ned Kynaston specialized in female roles until King Charles II's 1660 decree permitted women to perform on stage.[2] This shift forces Kynaston to confront the distinction between his onstage persona as Desdemona and his offstage identity, highlighting how sustained role-playing can blur the boundaries between artifice and authenticity.[11] Central to the narrative is the theme of identity crisis precipitated by societal and legal changes in theatrical conventions. Kynaston's inability to adapt to male roles after the ban on boy actors playing women underscores the rigidity of gender expectations imposed by cultural norms, as his professional and personal life had revolved around embodying femininity.[12] The film portrays this not as inherent biological determinism but as a consequence of performative habits ingrained over years, leading to existential questions about selfhood when external validation of one's constructed identity is revoked.[13] The interplay between performance and reality extends to sexuality, depicted through Kynaston's relationships and experiments with gender switching in intimate settings. Interactions with his dresser Maria, who impersonates him and later becomes an actress, reveal tensions between homosexual inclinations and heterosexual attractions, framed as explorations rather than fixed orientations.[14] This fluidity challenges binary views of desire, tying it to the theatrical world's emphasis on role-playing over innate traits.[1] Ambition and rivalry in the arts form another layer, as characters navigate jealousy and innovation amid the king's patronage and the rise of authentic female performers. The decree's implementation, while historically advancing women's participation, disrupts established artists, illustrating how institutional reforms can prioritize novelty over merit in creative fields.[15]Historical Context

Restoration-Era Theatre Conventions

Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, English theatres reopened after an 18-year closure under Puritan rule, introducing conventions influenced by continental practices observed by Charles II during his exile.[16] King Charles II granted patents to two companies—the King's Company and the Duke's Company—establishing a duopoly that controlled professional performances and emphasized professionalization with fixed repertories of new and revived plays.[17] A pivotal shift occurred with the admission of women to the stage, ending the pre-Commonwealth tradition where adolescent boys portrayed female characters; the first documented professional female performance was Margaret Hughes as Desdemona in Othello on December 8, 1660.[18] In 1662, Charles II formalized this change via a royal warrant mandating that "all women's parts to be acted by women," drawing from French theatrical norms where females had long performed such roles, though some male actors like Edward Kynaston continued female impersonations briefly thereafter, with Kynaston's final such role in 1661.[19][20] This innovation spurred the popularity of breeches roles, where women played youthful male characters in trousers, accentuating their legs for audience titillation in comedies by playwrights like Aphra Behn and William Congreve, thus inverting prior gender conventions while commodifying female performers' physicality.[21] Staging evolved to proscenium-arch designs with painted perspective scenery on flats, movable wings, and borders, enabling scene changes via shutters and incorporating French-inspired machines for spectacle, though practical limitations often restricted elaborate effects to major houses like Drury Lane.[22] Acting emphasized rhetorical delivery, with frequent asides—direct addresses to the audience commenting on action—and soliloquies revealing inner thoughts, conventions that blurred the fourth wall to foster intimacy in the intimate auditorium seating up to 700 patrons across pit, boxes, and galleries.[23] Performances ran repertory-style, with actors juggling multiple roles weekly, prioritizing wit, sexual intrigue, and social satire over realism, supported by minimal props and costumes denoting status rather than historical fidelity.[24] These elements reflected a courtly, libertine ethos, contrasting Puritan austerity, though economic pressures from the duopoly led to adaptations like afterpieces to retain audiences.[16]Key Historical Figures and Events

The Restoration of Charles II to the English throne on May 29, 1660, ended the Puritan suppression of theater, leading to the reopening of playhouses and the establishment of two patent companies: the King's Company under Thomas Killigrew and the Duke's Company under William Davenant. These companies revived professional drama, initially continuing the pre-Commonwealth tradition of boy actors portraying female roles. On December 24, 1662, Charles II issued a royal warrant decreeing that "all the women's parts to be acted in either of the said two companies henceforth must be performed by women," formalizing the shift from male impersonators to actresses, a practice the king had observed in France during his exile. This change, aimed at aligning English theater with continental conventions, disrupted careers reliant on female impersonation while opening opportunities for women on stage.[19] Edward Kynaston (c. 1640–1712), a leading Restoration actor, exemplified the boy player tradition, renowned for his convincing portrayals of women such as Desdemona in Othello. Samuel Pepys recorded on January 26, 1661, that Kynaston, then about 20, appeared "beyond all imagination the handsomest woman I ever saw in my life" in a female role. Having apprenticed under Thomas Betterton in the 1650s at a bookseller's shop, Kynaston debuted professionally around 1660 with Rhodes's company before joining Davenant's Duke's Company; post-decree, he adapted to male roles like Henry IV but retired by 1699 due to failing memory.[25] Thomas Betterton (1635–1710), the preeminent male actor and manager of the Duke's Company from 1660, trained Kynaston and dominated the Restoration stage in tragic roles, contributing to the era's theatrical innovations amid the transition to mixed-gender casts.[26] Nell Gwyn (1650–1687), one of the first prominent actresses, began as an orange seller at the King's Theatre before debuting onstage around 1665 with Killigrew's company, excelling in comic breeches roles and gaining fame for her wit; by 1668, she became Charles II's mistress, retiring from acting in 1671.[27] Her success highlighted the rapid rise enabled by the 1662 warrant, though actresses often faced moral scrutiny and typecasting in risqué parts.[28]Production

Development and Adaptation

Compleat Female Stage Beauty, the stage play by Jeffrey Hatcher that served as the basis for the film, premiered in 1999.[29] Hatcher, a prolific American playwright, crafted the work as an exploration of gender performance in Restoration-era theater, drawing loosely from the historical actor Edward Kynaston while incorporating fictional elements.[30] Hatcher personally adapted his play for the screen, shortening the title to Stage Beauty to streamline the narrative for cinematic pacing and visual emphasis on theatrical intrigue.[10] In April 2002, director Richard Eyre, known for his theater background including stints at the National Theatre, was attached to direct the adaptation, with production handled by Artisan Pictures and Tribeca Productions.[31] This collaboration preserved the play's witty dialogue and psycho-sexual tensions but incorporated broader historical Restoration context to enhance dramatic scope on film.[32]Filming Process and Challenges

Principal photography for Stage Beauty spanned eight weeks, with filming conducted on locations throughout London and on constructed sets at Shepperton Studios.[33] Specific sites included the Baroque sections of Hampton Court Palace, such as King William III's orangery, to authentically recreate Restoration-era interiors and exteriors.[34] The production faced challenges inherent to period dramas, particularly in replicating 17th-century theatrical conventions and costumes. Lead actor Billy Crudup, portraying Edward "Ned" Kynaston, encountered physical restrictions from the elaborate wardrobe, including corsets that he described as "terribly disconcerting" due to their encumbering nature, which complicated movement and scene preparation.[35] Director Richard Eyre emphasized integrating stage-like elements into the cinematic frame, drawing from theatrical inspirations to depict acting styles of the era, while navigating the tension between overt theatricality and film realism.[36] These elements demanded rigorous rehearsal to balance historical fidelity with performative demands.Cast and Crew

Principal Actors and Roles

Billy Crudup portrayed Ned Kynaston, a celebrated Restoration-era actor renowned for his portrayals of female characters on the English stage before the 1660 ban on male actors in such roles was lifted.[1][6] Kynaston's character grapples with identity and career upheaval following King Charles II's decree allowing women to perform.[37] Claire Danes played Maria, Kynaston's devoted dresser who secretly masters his techniques and seizes the opportunity to perform as Desdemona in Othello, igniting changes in theatre conventions.[1][6] Her role highlights the transition from male to female performers and the personal ambitions driving it.[38] Tom Wilkinson embodied Thomas Betterton, the pragmatic theatre manager and actor who navigates the shifting professional landscape amid royal edicts and competitive pressures.[39][40] Rupert Everett depicted King Charles II, whose whimsical decree in 1660 permits women on stage, catalyzing the film's central conflicts.[39][1]Director and Key Technical Contributors

Richard Eyre directed Stage Beauty, a 2004 historical drama adapted from Jeffrey Hatcher's play Compleat Female Stage Beauty.[1] Eyre, known for his work in British theatre including stints as artistic director of the Royal National Theatre (1988–1997) and the Royal Lyceum Theatre (1981–1988), emphasized authentic period staging and performance dynamics in the film.[6] His direction drew on Restoration theatre conventions, focusing on the transition from male to female performers on English stages following Charles II's 1660 decree.[5] The cinematography was led by Andrew Dunn, who employed period-appropriate lighting and composition to evoke 17th-century London theatre houses and interiors.[41] Dunn's work, shot primarily on location in the UK, utilized natural and candlelit effects to enhance the film's intimate, stage-like visual texture.[5] Editing by Tariq Anwar maintained narrative momentum across the dual timelines of theatrical intrigue and personal downfall, with precise cuts mirroring the rhythm of Restoration comedies.[41] Anwar, a veteran of films like The King's Speech (2010), ensured seamless integration of dialogue-heavy scenes and dramatic reveals.[42] George Fenton composed the original score, blending baroque influences with subtle modern orchestration to underscore emotional arcs without overpowering the period authenticity.[41] Fenton's contributions, including harpsichord and string motifs, complemented the film's exploration of gender and performance, drawing from historical English music traditions.[5] Production design by Tim Hatley recreated opulent yet gritty 1660s environments, with detailed sets for playhouses like the Duke's Theatre.[41] Hatley, who also designed costumes, focused on historically accurate fabrics and silhouettes to distinguish courtly excess from backstage realism.[43]Release and Commercial Performance

Distribution and Premiere Details

The film Stage Beauty premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City on May 8, 2004.[44] In the United Kingdom, it received a theatrical release on September 3, 2004, distributed by Momentum Pictures.[10] The United States saw a limited theatrical rollout on October 8, 2004, handled by Lionsgate Films, initially across three theaters.[45][6] International distribution varied, with releases in countries such as France on September 5, 2004, and Australia via Dendy Films later that year.[44][46]Box Office Results

Stage Beauty premiered in the United Kingdom on September 3, 2004, before receiving a limited release in the United States on October 8, 2004, distributed by Lionsgate Films.[47] The film opened in three theaters, generating $38,654 in its debut weekend ending October 10, 2004.[47] Over its domestic run, it earned a total of $782,383 from North American theaters.[47] Worldwide box office receipts reached $2,307,092, with the majority derived from international markets following the U.S. release.[1]Critical and Public Reception

Contemporary Reviews and Analysis

Upon its release in 2004, Stage Beauty received mixed reviews from critics, earning a 64% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 126 reviews, with a weighted average score of 6.5/10; the site's consensus described it as "uneven but enjoyable," highlighting its use of historical events for a well-acted romance infused with Shakespearean elements.[6] Similarly, Metacritic aggregated a score of 64/100 from 38 critics, reflecting a divide between praise for its theatrical flair and criticism of its dramatic execution.[7] Roger Ebert awarded the film three out of four stars, lauding its exploration of gender-bending in Restoration-era theater as a "royal treat" that captures the era's shift from Puritan repression to monarchical indulgence, with Billy Crudup's portrayal of Ned Kynaston standing out for its emotional depth in scenes of vulnerability and reinvention.[2] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone echoed this, calling it "bawdy fun" expertly directed by Richard Eyre, particularly commending Crudup's audition sequence for piercing emotional resonance amid the film's period authenticity.[48] In contrast, A.O. Scott of The New York Times found the drama "timorous and ungainly," critiquing Claire Danes's performance as Maria as stiff and accent-bound, while arguing the narrative's resolution felt contrived in its handling of Kynaston's identity crisis.[49] Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian characterized it as "picturesque Restoration rompery" laden with visual excesses like merkins and tavern scenes, but faulted its superficial treatment of deeper theatrical and social upheavals.[50] Analyses often centered on the film's thematic ambitions versus its execution, with critics like Ed Gonzalez of Slant Magazine rating it 2.5/4 for fictionalizing Edward Kynaston's life in a way that prioritized gender identity struggles post-Charles II's decree allowing women on stage, yet stumbling into uneven tonal shifts between comedy and pathos.[51] Some reviewers, including those in Variety, noted its cinematic revelry in language and performance despite the stage-bound origins, positioning it as a respectful nod to Restoration drama without fully transcending costume-piece conventions.[10] Early discourse also touched on perceived narrative conservatism, with outlets observing the arc of Kynaston's attraction evolving from performative femininity to authentic masculinity as potentially reductive, though defended by others as reflective of historical opportunism rather than modern ideological imposition.[52] Overall, the film's strengths in casting and production design were frequently cited as salvaging its flaws, contributing to a reception that valued its intellectual provocation over unqualified acclaim.Long-Term Audience Perspectives

Over two decades after its 2004 release, Stage Beauty has maintained a solid audience approval rating of 7.1 out of 10 on IMDb, based on more than 11,000 user votes, reflecting consistent appreciation for its performances and thematic depth among viewers interested in historical dramas.[1] On Rotten Tomatoes, the audience score stands at 78% from over 10,000 ratings, surpassing the 64% critics' Tomatometer and indicating that general viewers value the film's entertainment value and character-driven narrative more than professional reviewers did initially.[6] User reviews frequently highlight Billy Crudup's portrayal of Edward "Ned" Kynaston as transformative, with comments describing it as "awe-inspiring" for capturing the actor's internal conflict over gender performance and identity, contributing to the film's replay value for theater aficionados.[53] The film has cultivated a niche cult following, particularly among fringe theater enthusiasts and fans of Restoration-era history, where it is praised for blending bawdy humor with insights into the evolution of stage acting and the ban on female performers. Retrospective audience discussions on platforms like Letterboxd note its appeal as a "slow-burn cult classic" for those drawn to early 2000s British costume dramas featuring ensemble casts of stage actors, emphasizing its quotable dialogue and visual opulence over plot predictability. This enduring draw stems from the film's exploration of performance as artifice, resonating with viewers who revisit it for educational value on 17th-century English theater practices, such as boy actors specializing in female roles, rather than modern ideological overlays.[54] In reassessments, audiences often contrast the film's sympathetic depiction of Kynaston's professional displacement with real historical shifts post-1660, when King Charles II's decree allowed women on stage, viewing it as an accessible entry point to debates on acting authenticity without overt didacticism.[55] While some long-term viewers critique its fictional liberties—such as amplified romantic subplots—most prioritize the ensemble's chemistry, including Claire Danes' evolution from novice to performer, as a highlight that sustains interest in streaming-era rewatches.[56] This perspective underscores a broader audience preference for the movie's wit and historical texture, evidenced by steady ratings stability since the mid-2000s, over contemporaneous critical quibbles about pacing or anachronisms.[1]Awards and Recognition

Major Award Nominations and Wins

Stage Beauty garnered modest recognition from select critics' organizations, lacking nominations from major ceremonies such as the Academy Awards or British Academy Film Awards. The National Board of Review awarded the film Special Recognition for Excellence in Filmmaking in 2004, a shared honor also given to Undertow and The Woodsman.[57] The Phoenix Film Critics Society named it Overlooked Film of the Year in 2004, highlighting its underappreciated qualities amid limited commercial success.[58]| Awarding Body | Year | Category | Nominee/Recipient | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Board of Review, USA | 2004 | Special Recognition for Excellence in Filmmaking | Stage Beauty | Win (shared) |

| Phoenix Film Critics Society | 2004 | Overlooked Film of the Year | Stage Beauty | Win |

| London Film Critics' Circle | 2005 | British Supporting Actor of the Year | Rupert Everett | Nomination |