Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Juggernaut

View on Wikipedia

A juggernaut (/ˈdʒʌɡənɔːt/ ⓘ),[1] in current English usage, is a literal or metaphorical force regarded as merciless, destructive, and unstoppable. The term frequently implies an out-of-control force or object.

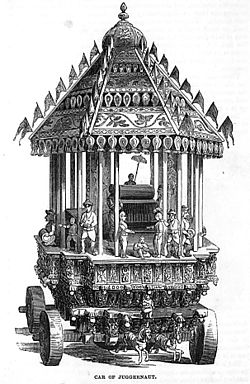

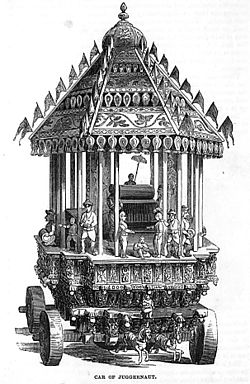

This English usage originates in the mid-nineteenth century. Juggernaut is the early rendering in English of Jagannath, an important deity in the Hindu traditions of eastern and north-eastern India. The meaning originates from the Hindu temple cars, which are chariots, often huge, used in processions or religious parades for Jagannath and other deities, the largest of which, once set into motion, are difficult to stop, steer or control by humans, on account of their massive weight.

Since the Middle Ages, Europeans had been fascinated by accounts of the Ratha Yatra (lit. 'temple car procession') at Puri, which claimed that pilgrims threw themselves under the temple cars. However, by 1825 it was said: "That excess of fanaticism which formerly prompted the pilgrims to court death by throwing themselves in crowds under the wheels of the car of Jaganath, has happily long ceased."[2] Despite this, a New York Times report from 1864 reported witnessing celebrants deliberately placing themselves under the wheels of the device against the will of the authorities. [3]

Overview

[edit]The figurative use of the word is analogous to figurative uses of steamroller or battering ram to mean something overwhelming. Its ground in social behavior is similar to that of bandwagon, but with overtones of devotional sacrifice. Its British English meaning of a large heavy truck[4] or articulated lorry dates from the second half of the twentieth century.[5]

The word is derived from the Sanskrit/Odia Jagannātha (Devanagari जगन्नाथ, Odia ଜଗନ୍ନାଥ) "world-lord", combining jagat ("world") and nātha ("lord"), which is one of the names of Krishna found in the Sanskrit epics.[6]

The English loanword juggernaut in the sense of "a huge wagon bearing an image of a Hindu god" is from the seventeenth century, inspired by the Jagannatha Temple in Puri, Odisha (Orissa), which has the Ratha Yatra ("Temple car procession"), an annual procession of chariots carrying the murtis (images) of Jagannātha, Subhadra, and Balabhadra.

The first European description of this festival is found in a thirteenth-century account by the Late Medieval Franciscan friar and missionary Odoric of Pordenone, who describes Hindus, as a religious sacrifice, casting themselves under the wheels of these huge chariots and being crushed to death. Odoric's description was later taken up and elaborated upon in the popular fourteenth-century Travels of John Mandeville.[7] Others have suggested more prosaically that the deaths, if any, were accidental and caused by the press of the crowd and the general commotion.[8] Contemporaneous reports from colonial Kolkata report witnessing intentional suicides at the processions which were either tacitly allowed or else ignored by clerics, despite the practice being prohibited by government policy. [9]

Many speakers and writers apply the term to a large machine, or collectively to a team or group of people working together (such as a highly successful sports team or corporation), or even a growing political movement led by a charismatic leader—and it often bears an association with being crushingly destructive towards all obstacles.

In popular culture

[edit]The figurative sense of the English word juggernaut, as a merciless, destructive, and unstoppable force, became common in the mid-nineteenth century. Mary Shelley used the term in her novel The Last Man, published in 1826, to describe the plague: "like Juggernaut, she proceeds crushing out the being of all who strew the high road of life". Charles Dickens used the term in The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, published in 1844, to describe the love-lorn sentiments of Mr. Augustus Moddle, the 'youngest gentleman' at Mrs. Todgers's: "He often informed Mrs. Todgers that the sun had set upon him; that the billows had rolled over him; that the Car of Juggernaut had crushed him; and also that the deadly Upass tree of Java had blighted him." Robert Louis Stevenson used the term in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, published in 1886, when describing the violent Edward Hyde as "like some damned Juggernaut" after he trampled a child.

Other notable writers to have used the word this way range from H. G. Wells and Longfellow[5] to Joe Klein. Bill Wilson in Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions of Alcoholics Anonymous describes "self-sufficiency" in society at large as being a "bone-crushing juggernaut whose final achievement is ruin". To the contrary, Mark Twain (autobiography, vol 2), describes Juggernaut as the kindest of gods. Any pretensions to rank or caste do not exist within its temple.

Juggernaut (Cain Marko) is a fictional character appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics.[10] Created by writer Stan Lee and artist/co-writer Jack Kirby, he first appeared in X-Men #12 (July 1965) as an adversary of the eponymous superhero team.[11] He possesses superhuman strength and durability, and is virtually immune to most physical attacks; his helmet also protects him from mental attacks.

In the future wars depicted in John Shirley's Eclipse Trilogy, the contending armies use "Jaegernauts" — large rolling war machines that can destroy entire city blocks, high rises and other large buildings.

The Odisha Juggernauts are a sports team in the Indian Ultimate Kho Kho league.[12]

Juggernaut is a multiplayer game mode in the video game series Halo, whereby players work together to defeat a common enemy (the Juggernaut). Once a player kills the current Juggernaut, they then become the next Juggernaut.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ OED, "Juggernaut":1

- ^

"AFFAIRS IN INDIA.; The Great Juggernaut Saturnalia. The Sacrifice of Human Victims". Archived from the original on 2024-12-29. Retrieved 2025-01-04.

The car had been in one place for a whole year, and had made a deep hole for itself by its great weight. Again and again the Brahmins-shouted and gesticulated, laughing among themselves. At last the mob happened to pull together instead of one after the other, and the huge mass moved forward a few yards, groaning as if it had been a living creature. It stopped, and for a few minutes the crowd stood in almost perfect silence. Then the Brahimns again gave the signal, and this time it crushed out a life with every revolution of its hideous wheels, covered as they were with human flesh and gore.

- ^ "Definition of Juggernaut". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Juggernaut". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "djuggernaut". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-13. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ Folker Reichert, Asien und Europa im Mittelalter Archived 2023-04-04 at the Wayback Machine, p. 353; OED, "Juggernaut":1

- ^ "Rath Yatra: The Chariot Festival of Puri, India". Archived from the original on 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ^ The mob cried out "Apse, apse" -- that they did it of their own accord; and, indeed, there was no appearance of an accident. Their bodies were far under the car, where they count scarcely have got unless they had laid themselves down in front. "AFFAIRS IN INDIA.; The Great Juggernaut Saturnalia. The Sacrifice of Human Victims". Archived from the original on 2024-12-29. Retrieved 2025-01-04.

- ^ Rovin, Jeff (1987). The Encyclopedia of Super-Villains. New York: Facts on File. p. 172. ISBN 0-8160-1356-X.

- ^ DeFalco, Tom; Sanderson, Peter; Brevoort, Tom; Teitelbaum, Michael; Wallace, Daniel; Darling, Andrew; Forbeck, Matt; Cowsill, Alan; Bray, Adam (2019). The Marvel Encyclopedia. DK Publishing. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4654-7890-0.

- ^ R, Gopalakrishnan (2022-08-29). ""Women's League in Pipeline": Ultimate Kho Kho CEO Tenzing Niyogi". www.sportskeeda.com. Retrieved 2023-12-16.