Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Steering column

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

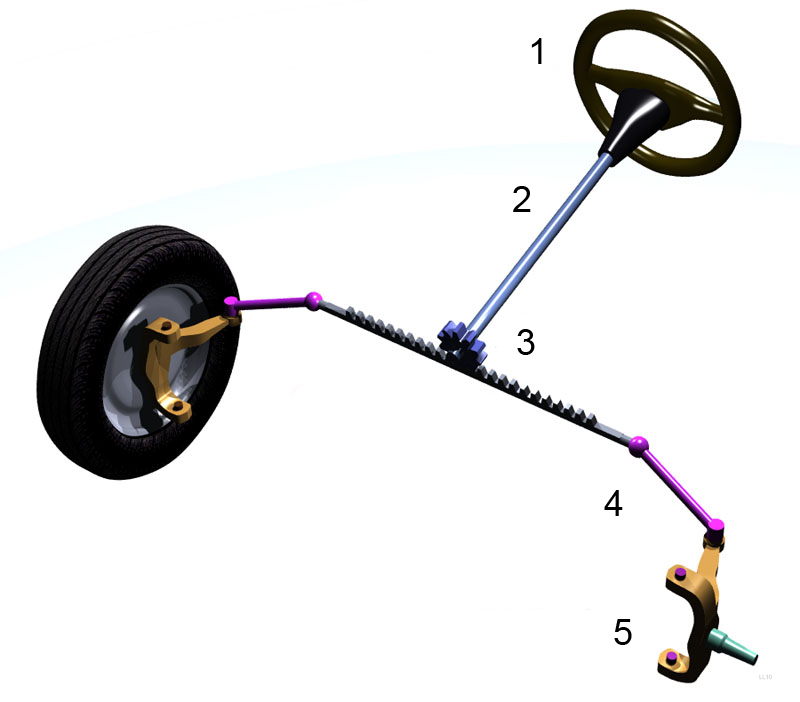

- Steering wheel

- Steering column

- Rack and pinion

- Steering arm

- Steering knuckle

2 case

3 Steering column (hidden by the case - blue dashed line)

4 Universal joint

The automotive steering column is a device intended primarily for connecting the steering wheel to the steering mechanism.

Secondary functions

[edit]A steering column may also perform the following secondary functions:

- energy dissipation management in the event of a frontal collision;

- provide mounting for: the multi-function switch, column lock, column wiring, column shroud(s), transmission gear selector, gauges or other instruments as well as the electro motor and gear units found in EPAS and SbW systems;

- offer (height and/or length) adjustment to suit driver preference

Steering lock

[edit]Modern vehicles are fitted with a steering lock which is an anti-theft device. It is fitted to the steering column usually below the steering wheel. The lock is combined with the ignition switch and engaged and disengaged either by a mechanical ignition key or electronically from the vehicles electronic control unit. These locks were introduced on many General Motors products in 1969 drastically reducing thefts of these GM models,[1] and on Ford, Chrysler, and AMC products in 1970.

Collapsible column

[edit]A common device to enhance car safety is the collapsible steering column. This is designed to collapse in the event of a collision to protect the driver from harm. The column can collapse after impact with a tolerance ring inserted between the inner shaft of the steering column and the external housing. The wavelike protrusions on the circumference of the tolerance ring act as a spring to hold the two parts in place in normal driving conditions. At a specific level of force, for example in the event of a collision, the tolerance ring allows the inner shaft to slip inside the housing, so the column can collapse, absorbing energy from the impact.[2] In 1967, General Motors introduced its 'energy absorbing' steering column which consisted of a lattice-mesh outer tube section which was designed to crush on impact whilst the inner shaft telescoped. This column design first appeared on Chevrolet vehicles, and was rolled out to all of GM's divisions worldwide in the following years.

In virtually all modern vehicles, the lower section of the inner shaft is articulated with universal joints which helps control movement of the column in a frontal impact, and also gives engineers freedom in mounting the steering gear itself.

Regulatory requirements

[edit]In the United States, steering columns are governed by several federal regulatory requirements, notably FMVSS 108, 114 and 208. The Chinese directive GB15740- 2006 obligates Chinese car manufacturers to incorporate anti-theft mechanisms in their vehicles.[3] European Union Commission Directive 95/56/EC (1995) mandates all cars exported to European markets must be fitted with anti-theft security devices. This regulation also requires that a steering lock must be able to withstand forces of 100Nm applied to the steering wheel without failing.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Popular Science Anti-Car-Theft Device Competition" Popular Science, July 1969, p.70.

- ^ "Collapsible Steering Column Relies on Tolerance Rings". Machine Design. 7 April 2009. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ "GB 15740-2006 English version, GB 15740-2006 Protective devices against unauthorized use of motor vehicles (English) - Code of China". Code of China. Chinese Government. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ Commission Directive 95/56/EC, Euratom of 8 November 1995 adapting to technical progress Council Directive 74/61/EEC relating to devices to prevent the unauthorized use of motor vehicles