Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polymer

View on Wikipedia

| Polymer science |

|---|

|

A polymer is a substance composed of macromolecules.[2] A macromolecule is a molecule of high relative molecular mass, the structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass.[3]

A polymer (/ˈpɒlɪmər/[4][5]) is a substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers.[6] Due to their broad spectrum of properties,[7] both synthetic and natural polymers play essential and ubiquitous roles in everyday life.[8] Polymers range from familiar synthetic plastics such as polystyrene to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are fundamental to biological structure and function. Polymers, both natural and synthetic, are created via polymerization of many small molecules, known as monomers. Their consequently large molecular mass, relative to small molecule compounds, produces unique physical properties including toughness, high elasticity, viscoelasticity, and a tendency to form amorphous and semicrystalline structures rather than crystals.

Polymers are studied in the fields of polymer science (which includes polymer chemistry and polymer physics), biophysics and materials science and engineering. Historically, products arising from the linkage of repeating units by covalent chemical bonds have been the primary focus of polymer science. An emerging important area now focuses on supramolecular polymers formed by non-covalent links. Polyisoprene of latex rubber is an example of a natural polymer, and the polystyrene of styrofoam is an example of a synthetic polymer. In biological contexts, essentially all biological macromolecules—i.e., proteins (polyamides), nucleic acids (polynucleotides), and polysaccharides—are purely polymeric, or are composed in large part of polymeric components.

Etymology

[edit]The term "polymer" derives from Greek πολύς (polus) 'many, much' and μέρος (meros) 'part'. The term was coined in 1833 by Jöns Jacob Berzelius, though with a definition distinct from the modern IUPAC definition.[9][10] The modern concept of polymers as covalently bonded macromolecular structures was proposed in 1920 by Hermann Staudinger,[11] who spent the next decade finding experimental evidence for this hypothesis.[12]

Common examples

[edit]

Polymers are of two types: naturally occurring and synthetic or man made.

Natural

[edit]Natural polymeric materials such as hemp, shellac, amber, wool, silk, and natural rubber have been used for centuries. A variety of other natural polymers exist, such as cellulose, which is the main constituent of wood and paper.

Space polymer

[edit]Hemoglycin (previously termed hemolithin) is a space polymer that is the first polymer of amino acids found in meteorites.[13][14][15]

Synthetic

[edit]The list of synthetic polymers, roughly in order of worldwide demand, includes polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride, synthetic rubber, phenol formaldehyde resin (or Bakelite), neoprene, nylon, polyacrylonitrile, PVB, silicone, and many more. More than 330 million tons of these polymers are made every year (2015).[16]

Most commonly, the continuously linked backbone of a polymer used for the preparation of plastics consists mainly of carbon atoms. A simple example is polyethylene ('polythene' in British English), whose repeat unit or monomer is ethylene. Many other structures do exist; for example, elements such as silicon form familiar materials such as silicones, examples being Silly Putty and waterproof plumbing sealant. Oxygen is also commonly present in polymer backbones, such as those of polyethylene glycol, polysaccharides (in glycosidic bonds), and DNA (in phosphodiester bonds).

Synthesis

[edit]

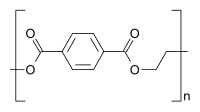

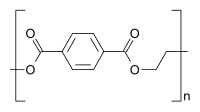

Polymerization is the process of combining many small molecules known as monomers into a covalently bonded chain or network. During the polymerization process, some chemical groups may be lost from each monomer. This happens in the polymerization of PET polyester. The monomers are terephthalic acid (HOOC—C6H4—COOH) and ethylene glycol (HO—CH2—CH2—OH) but the repeating unit is —OC—C6H4—COO—CH2—CH2—O—, which corresponds to the combination of the two monomers with the loss of two water molecules. The distinct piece of each monomer that is incorporated into the polymer is known as a repeat unit or monomer residue.

Synthetic methods are generally divided into two categories, step-growth polymerization and chain polymerization.[17] The essential difference between the two is that in chain polymerization, monomers are added to the chain one at a time only,[18] such as in polystyrene, whereas in step-growth polymerization chains of monomers may combine with one another directly,[19] such as in polyester. Step-growth polymerization can be divided into polycondensation, in which low-molar-mass by-product is formed in every reaction step, and polyaddition.

Newer methods, such as plasma polymerization do not fit neatly into either category. Synthetic polymerization reactions may be carried out with or without a catalyst. Laboratory synthesis of biopolymers, especially of proteins, is an area of intensive research.

Biological synthesis

[edit]

There are three main classes of biopolymers: polysaccharides, polypeptides, and polynucleotides. In living cells, they may be synthesized by enzyme-mediated processes, such as the formation of DNA catalyzed by DNA polymerase. The synthesis of proteins involves multiple enzyme-mediated processes to transcribe genetic information from the DNA to RNA and subsequently translate that information to synthesize the specified protein from amino acids. The protein may be modified further following translation in order to provide appropriate structure and functioning. There are other biopolymers such as rubber, suberin, melanin, and lignin.

Modification of natural polymers

[edit]Naturally occurring polymers such as cotton, starch, and rubber were familiar materials for years before synthetic polymers such as polyethene and perspex appeared on the market. Many commercially important polymers are synthesized by chemical modification of naturally occurring polymers. Prominent examples include the reaction of nitric acid and cellulose to form nitrocellulose and the formation of vulcanized rubber by heating natural rubber in the presence of sulfur. Ways in which polymers can be modified include oxidation, cross-linking, and end-capping.

Structure

[edit]The structure of a polymeric material can be described at different length scales, from the sub-nm length scale up to the macroscopic one. There is in fact a hierarchy of structures, in which each stage provides the foundations for the next one.[20] The starting point for the description of the structure of a polymer is the identity of its constituent monomers. Next, the microstructure essentially describes the arrangement of these monomers within the polymer at the scale of a single chain. The microstructure determines the possibility for the polymer to form phases with different arrangements, for example through crystallization, the glass transition or microphase separation.[21] These features play a major role in determining the physical and chemical properties of a polymer.

Monomers and repeat units

[edit]The identity of the repeat units (monomer residues, also known as "mers") comprising a polymer is its first and most important attribute. Polymer nomenclature is generally based upon the type of monomer residues comprising the polymer. A polymer which contains only a single type of repeat unit is known as a homopolymer, while a polymer containing two or more types of repeat units is known as a copolymer.[22] A terpolymer is a copolymer which contains three types of repeat units.[23]

Polystyrene is composed only of styrene-based repeat units, and is classified as a homopolymer. Polyethylene terephthalate, even though produced from two different monomers (ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid), is usually regarded as a homopolymer because only one type of repeat unit is formed. Ethylene-vinyl acetate contains more than one variety of repeat unit and is a copolymer. Some biological polymers are composed of a variety of different but structurally related monomer residues; for example, polynucleotides such as DNA are composed of four types of nucleotide subunits.

Homopolymers and copolymers (examples)

Homopolymer polystyrene Homopolymer polydimethylsiloxane, a silicone. The main chain is formed of silicon and oxygen atoms. The homopolymer polyethylene terephthalate has only one repeat unit. Copolymer styrene-butadiene rubber: The repeat units based on styrene and 1,3-butadiene form two repeating units, which can alternate in any order in the macromolecule, making the polymer thus a random copolymer.

A polymer containing ionizable subunits (e.g., pendant carboxylic groups) is known as a polyelectrolyte or ionomer, when the fraction of ionizable units is large or small respectively.

Microstructure

[edit]The microstructure of a polymer (sometimes called configuration) relates to the physical arrangement of monomer residues along the backbone of the chain.[24] These are the elements of polymer structure that require the breaking of a covalent bond in order to change. Various polymer structures can be produced depending on the monomers and reaction conditions: A polymer may consist of linear macromolecules containing each only one unbranched chain. In the case of unbranched polyethylene, this chain is a long-chain n-alkane. There are also branched macromolecules with a main chain and side chains, in the case of polyethylene the side chains would be alkyl groups. In particular unbranched macromolecules can be in the solid state semi-crystalline, crystalline chain sections highlighted red in the figure below.

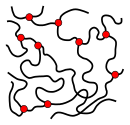

While branched and unbranched polymers are usually thermoplastics, many elastomers have a wide-meshed cross-linking between the "main chains". Close-meshed crosslinking, on the other hand, leads to thermosets. Cross-links and branches are shown as red dots in the figures. Highly branched polymers are amorphous and the molecules in the solid interact randomly.

Linear, unbranched macromolecule

Branched macromolecule

Semi-crystalline structure of an unbranched polymer

Slightly cross-linked polymer (elastomer)

Highly cross-linked polymer (thermoset)

Polymer architecture

[edit]

An important microstructural feature of a polymer is its architecture and shape, which relates to the way branch points lead to a deviation from a simple linear chain.[25] A branched polymer molecule is composed of a main chain with one or more substituent side chains or branches. Types of branched polymers include star polymers, comb polymers, polymer brushes, dendronized polymers, ladder polymers, and dendrimers.[25] There exist also two-dimensional polymers (2DP) which are composed of topologically planar repeat units. A polymer's architecture affects many of its physical properties including solution viscosity, melt viscosity, solubility in various solvents, glass-transition temperature and the size of individual polymer coils in solution. A variety of techniques may be employed for the synthesis of a polymeric material with a range of architectures, for example living polymerization.

Chain length

[edit]A common means of expressing the length of a chain is the degree of polymerization, which quantifies the number of monomers incorporated into the chain.[26][27] As with other molecules, a polymer's size may also be expressed in terms of molecular weight. Since synthetic polymerization techniques typically yield a statistical distribution of chain lengths, the molecular weight is expressed in terms of weighted averages. The number-average molecular weight (Mn) and weight-average molecular weight (Mw) are most commonly reported.[28][29] The ratio of these two values (Mw / Mn) is the dispersity (Đ), which is commonly used to express the width of the molecular weight distribution.[30]

The physical properties[31] of polymer strongly depend on the length (or equivalently, the molecular weight) of the polymer chain.[32] One important example of the physical consequences of the molecular weight is the scaling of the viscosity (resistance to flow) in the melt.[33] The influence of the weight-average molecular weight () on the melt viscosity () depends on whether the polymer is above or below the onset of entanglements. Below the entanglement molecular weight[clarification needed], , whereas above the entanglement molecular weight, . In the latter case, increasing the polymer chain length 10-fold would increase the viscosity over 1000 times.[34][page needed] Increasing chain length furthermore tends to decrease chain mobility, increase strength and toughness, and increase the glass-transition temperature (Tg).[35] This is a result of the increase in chain interactions such as van der Waals attractions and entanglements that come with increased chain length.[36][37] These interactions tend to fix the individual chains more strongly in position and resist deformations and matrix breakup, both at higher stresses and higher temperatures.

Monomer arrangement in copolymers

[edit]Copolymers are classified either as statistical copolymers, alternating copolymers, block copolymers, graft copolymers or gradient copolymers. In the schematic figure below, Ⓐ and Ⓑ symbolize the two repeat units.

Random copolymer

Gradient copolymer

Graft copolymer

Alternating copolymer

Block copolymer

- Alternating copolymers possess two regularly alternating monomer residues:[38] (AB)

n. An example is the equimolar copolymer of styrene and maleic anhydride formed by free-radical chain-growth polymerization.[39] A step-growth copolymer such as Nylon 66 can also be considered a strictly alternating copolymer of diamine and diacid residues, but is often described as a homopolymer with the dimeric residue of one amine and one acid as a repeat unit.[40] - Periodic copolymers have more than two species of monomer units in a regular sequence.[41]

- Statistical copolymers have monomer residues arranged according to a statistical rule. A statistical copolymer in which the probability of finding a particular type of monomer residue at a particular point in the chain is independent of the types of surrounding monomer residue may be referred to as a truly random copolymer.[42][43] For example, the chain-growth copolymer of vinyl chloride and vinyl acetate is random.[39]

- Block copolymers have long sequences of different monomer units.[39][40] Polymers with two or three blocks of two distinct chemical species (e.g., A and B) are called diblock copolymers and triblock copolymers, respectively. Polymers with three blocks, each of a different chemical species (e.g., A, B, and C) are termed triblock terpolymers.

- Graft or grafted copolymers contain side chains or branches whose repeat units have a different composition or configuration than the main chain.[40] The branches are added on to a preformed main chain macromolecule.[39]

Monomers within a copolymer may be organized along the backbone in a variety of ways. A copolymer containing a controlled arrangement of monomers is called a sequence-controlled polymer.[44] Alternating, periodic and block copolymers are simple examples of sequence-controlled polymers.

Tacticity

[edit]Tacticity describes the relative stereochemistry of chiral centers in neighboring structural units within a macromolecule. There are three types of tacticity: isotactic (all substituents on the same side), atactic (random placement of substituents), and syndiotactic (alternating placement of substituents).

Morphology

[edit]Polymer morphology generally describes the arrangement and microscale ordering of polymer chains in space. The macroscopic physical properties of a polymer are related to the interactions between the polymer chains.

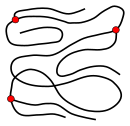

Randomly oriented polymer |

Interlocking of several polymers |

- Disordered polymers: In the solid state, atactic polymers, polymers with a high degree of branching and random copolymers form amorphous (i.e. glassy structures).[45] In melt and solution, polymers tend to form a constantly changing "statistical cluster", see freely-jointed-chain model. In the solid state, the respective conformations of the molecules are frozen. Hooking and entanglement of chain molecules lead to a "mechanical bond" between the chains. Intermolecular and intramolecular attractive forces only occur at sites where molecule segments are close enough to each other. The irregular structures of the molecules prevent a narrower arrangement.

Polyethylene: zigzag conformation of molecules in close packed chains |

Lamella with tie molecules |

Spherulite |

polypropylene helix |

p-Aramid, red dotted: hydrogen bonds |

- Linear polymers with periodic structure, low branching and stereoregularity (e. g. not atactic) have a semi-crystalline structure in the solid state.[45] In simple polymers (such as polyethylene), the chains are present in the crystal in zigzag conformation. Several zigzag conformations form dense chain packs, called crystallites or lamellae. The lamellae are much thinner than the polymers are long (often about 10 nm).[46] They are formed by more or less regular folding of one or more molecular chains. Amorphous structures exist between the lamellae. Individual molecules can lead to entanglements between the lamellae and can also be involved in the formation of two (or more) lamellae (chains than called tie molecules). Several lamellae form a superstructure, a spherulite, often with a diameter in the range of 0.05 to 1 mm.[46]

- The type and arrangement of (functional) residues of the repeat units effects or determines the crystallinity and strength of the secondary valence bonds. In isotactic polypropylene, the molecules form a helix. Like the zigzag conformation, such helices allow a dense chain packing. Particularly strong intermolecular interactions occur when the residues of the repeating units allow the formation of hydrogen bonds, as in the case of p-aramid. The formation of strong intramolecular associations may produce diverse folded states of single linear chains with distinct circuit topology. Crystallinity and superstructure are always dependent on the conditions of their formation, see also: crystallization of polymers. Compared to amorphous structures, semi-crystalline structures lead to a higher stiffness, density, melting temperature and higher resistance of a polymer.

- Cross-linked polymers: Wide-meshed cross-linked polymers are elastomers and cannot be molten (unlike thermoplastics); heating cross-linked polymers only leads to decomposition. Thermoplastic elastomers, on the other hand, are reversibly "physically crosslinked" and can be molten. Block copolymers in which a hard segment of the polymer has a tendency to crystallize and a soft segment has an amorphous structure are one type of thermoplastic elastomers: the hard segments ensure wide-meshed, physical crosslinking.

Wide-meshed cross-linked polymer (elastomer) |

Wide-meshed cross-linked polymer (elastomer) under tensile stress |

Crystallites as "crosslinking sites": one type of thermoplastic elastomer |

Semi-crystalline thermoplastic elastomer under tensile stress |

Crystallinity

[edit]When applied to polymers, the term crystalline has a somewhat ambiguous usage. In some cases, the term crystalline finds identical usage to that used in conventional crystallography. For example, the structure of a crystalline protein or polynucleotide, such as a sample prepared for x-ray crystallography, may be defined in terms of a conventional unit cell composed of one or more polymer molecules with cell dimensions of hundreds of angstroms or more. A synthetic polymer may be loosely described as crystalline if it contains regions of three-dimensional ordering on atomic (rather than macromolecular) length scales, usually arising from intramolecular folding or stacking of adjacent chains. Synthetic polymers may consist of both crystalline and amorphous regions; the degree of crystallinity may be expressed in terms of a weight fraction or volume fraction of crystalline material. Few synthetic polymers are entirely crystalline. The crystallinity of polymers is characterized by their degree of crystallinity, ranging from zero for a completely non-crystalline polymer to one for a theoretical completely crystalline polymer. Polymers with microcrystalline regions are generally tougher (can be bent more without breaking) and more impact-resistant than totally amorphous polymers.[47] Polymers with a degree of crystallinity approaching zero or one will tend to be transparent, while polymers with intermediate degrees of crystallinity will tend to be opaque due to light scattering by crystalline or glassy regions. For many polymers, crystallinity may also be associated with decreased transparency.

Chain conformation

[edit]The space occupied by a polymer molecule is generally expressed in terms of radius of gyration, which is an average distance from the center of mass of the chain to the chain itself. Alternatively, it may be expressed in terms of pervaded volume, which is the volume spanned by the polymer chain and scales with the cube of the radius of gyration.[48] The simplest theoretical models for polymers in the molten, amorphous state are ideal chains.

Properties

[edit]Polymer properties depend of their structure and they are divided into classes according to their physical bases. Many physical and chemical properties describe how a polymer behaves as a continuous macroscopic material. They are classified as bulk properties, or intensive properties according to thermodynamics.

Mechanical properties

[edit]

The bulk properties of a polymer are those most often of end-use interest. These are the properties that dictate how the polymer actually behaves on a macroscopic scale.

Tensile strength

[edit]The tensile strength of a material quantifies how much elongating stress the material will endure before failure.[49][50] This is very important in applications that rely upon a polymer's physical strength or durability. For example, a rubber band with a higher tensile strength will hold a greater weight before snapping. In general, tensile strength increases with polymer chain length and crosslinking of polymer chains.

Young's modulus of elasticity

[edit]Young's modulus quantifies the elasticity of the polymer. It is defined, for small strains, as the ratio of rate of change of stress to strain. Like tensile strength, this is highly relevant in polymer applications involving the physical properties of polymers, such as rubber bands. The modulus is strongly dependent on temperature. Viscoelasticity describes a complex time-dependent elastic response, which will exhibit hysteresis in the stress-strain curve when the load is removed. Dynamic mechanical analysis or DMA measures this complex modulus by oscillating the load and measuring the resulting strain as a function of time.

Transport properties

[edit]Transport properties such as diffusivity describe how rapidly molecules move through the polymer matrix. These are very important in many applications of polymers for films and membranes.

The movement of individual macromolecules occurs by a process called reptation in which each chain molecule is constrained by entanglements with neighboring chains to move within a virtual tube. The theory of reptation can explain polymer molecule dynamics and viscoelasticity.[51]

Phase behavior

[edit]Crystallization and melting

[edit]

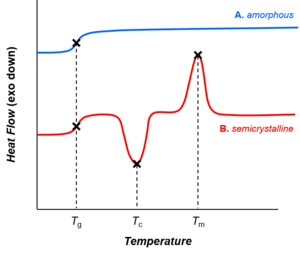

Depending on their chemical structures, polymers may be either semi-crystalline or amorphous. Semi-crystalline polymers can undergo crystallization and melting transitions, whereas amorphous polymers do not. In polymers, crystallization and melting do not suggest solid-liquid phase transitions, as in the case of water or other molecular fluids. Instead, crystallization and melting refer to the phase transitions between two solid states (i.e., semi-crystalline and amorphous). Crystallization occurs above the glass-transition temperature (Tg) and below the melting temperature (Tm).

Glass transition

[edit]All polymers (amorphous or semi-crystalline) go through glass transitions. The glass-transition temperature (Tg) is a crucial physical parameter for polymer manufacturing, processing, and use. Below Tg, molecular motions are frozen and polymers are brittle and glassy. Above Tg, molecular motions are activated and polymers are rubbery and viscous. The glass-transition temperature may be engineered by altering the degree of branching or crosslinking in the polymer or by the addition of plasticizers.[52]

Whereas crystallization and melting are first-order phase transitions, the glass transition is not.[53] The glass transition shares features of second-order phase transitions (such as discontinuity in the heat capacity, as shown in the figure), but it is generally not considered a thermodynamic transition between equilibrium states.

Mixing behavior

[edit]

In general, polymeric mixtures are far less miscible than mixtures of small molecule materials. This effect results from the fact that the driving force for mixing is usually entropy, not interaction energy. In other words, miscible materials usually form a solution not because their interaction with each other is more favorable than their self-interaction, but because of an increase in entropy and hence free energy associated with increasing the amount of volume available to each component. This increase in entropy scales with the number of particles (or moles) being mixed. Since polymeric molecules are much larger and hence generally have much higher specific volumes than small molecules, the number of molecules involved in a polymeric mixture is far smaller than the number in a small molecule mixture of equal volume. The energetics of mixing, on the other hand, is comparable on a per volume basis for polymeric and small molecule mixtures. This tends to increase the free energy of mixing for polymer solutions and thereby making solvation less favorable, and thereby making the availability of concentrated solutions of polymers far rarer than those of small molecules.

Furthermore, the phase behavior of polymer solutions and mixtures is more complex than that of small molecule mixtures. Whereas most small molecule solutions exhibit only an upper critical solution temperature phase transition (UCST), at which phase separation occurs with cooling, polymer mixtures commonly exhibit a lower critical solution temperature phase transition (LCST), at which phase separation occurs with heating.

In dilute solutions, the properties of the polymer are characterized by the interaction between the solvent and the polymer. In a good solvent, the polymer appears swollen and occupies a large volume. In this scenario, intermolecular forces between the solvent and monomer subunits dominate over intramolecular interactions. In a bad solvent or poor solvent, intramolecular forces dominate and the chain contracts. In the theta solvent, or the state of the polymer solution where the value of the second virial coefficient becomes 0, the intermolecular polymer-solvent repulsion balances exactly the intramolecular monomer-monomer attraction. Under the theta condition (also called the Flory condition), the polymer behaves like an ideal random coil. The transition between the states is known as a coil–globule transition.

Inclusion of plasticizers

[edit]Inclusion of plasticizers tends to lower Tg and increase polymer flexibility. Addition of the plasticizer will also modify dependence of the glass-transition temperature Tg on the cooling rate.[54] The mobility of the chain can further change if the molecules of plasticizer give rise to hydrogen bonding formation. Plasticizers are generally small molecules that are chemically similar to the polymer and create gaps between polymer chains for greater mobility and fewer interchain interactions. A good example of the action of plasticizers is related to polyvinylchlorides or PVCs. A uPVC, or unplasticized polyvinylchloride, is used for things such as pipes. A pipe has no plasticizers in it, because it needs to remain strong and heat-resistant. Plasticized PVC is used in clothing for a flexible quality. Plasticizers are also put in some types of cling film to make the polymer more flexible.

Chemical properties

[edit]The attractive forces between polymer chains play a large part in determining the polymer's properties. Because polymer chains are so long, they have many such interchain interactions per molecule, amplifying the effect of these interactions on the polymer properties in comparison to attractions between conventional molecules. Different side groups on the polymer can lend the polymer to ionic bonding or hydrogen bonding between its own chains. These stronger forces typically result in higher tensile strength and higher crystalline melting points.

The intermolecular forces in polymers can be affected by dipoles in the monomer units. Polymers containing amide or carbonyl groups can form hydrogen bonds between adjacent chains; the partially positively charged hydrogen atoms in N-H groups of one chain are strongly attracted to the partially negatively charged oxygen atoms in C=O groups on another. These strong hydrogen bonds, for example, result in the high tensile strength and melting point of polymers containing urethane or urea linkages. Polyesters have dipole-dipole bonding between the oxygen atoms in C=O groups and the hydrogen atoms in H-C groups. Dipole bonding is not as strong as hydrogen bonding, so a polyester's melting point and strength are lower than Kevlar's (Twaron), but polyesters have greater flexibility. Polymers with non-polar units such as polyethylene interact only through weak Van der Waals forces. As a result, they typically have lower melting temperatures than other polymers.

When a polymer is dispersed or dissolved in a liquid, such as in commercial products like paints and glues, the chemical properties and molecular interactions influence how the solution flows and can even lead to self-assembly of the polymer into complex structures. When a polymer is applied as a coating, the chemical properties will influence the adhesion of the coating and how it interacts with external materials, such as superhydrophobic polymer coatings leading to water resistance. Overall the chemical properties of a polymer are important elements for designing new polymeric material products.

Optical properties

[edit]Polymers such as PMMA and HEMA:MMA are used as matrices in the gain medium of solid-state dye lasers, also known as solid-state dye-doped polymer lasers. These polymers have a high surface quality and are also highly transparent so that the laser properties are dominated by the laser dye used to dope the polymer matrix. These types of lasers, that also belong to the class of organic lasers, are known to yield very narrow linewidths which is useful for spectroscopy and analytical applications.[55] An important optical parameter in the polymer used in laser applications is the change in refractive index with temperature also known as dn/dT. For the polymers mentioned here the (dn/dT) ~ −1.4 × 10−4 in units of K−1 in the 297 ≤ T ≤ 337 K range.[56]

Electrical properties

[edit]Most conventional polymers such as polyethylene are electrical insulators, but the development of polymers containing π-conjugated bonds has led to a wealth of polymer-based semiconductors, such as polythiophenes. This has led to many applications in the field of organic electronics.

Applications

[edit]Nowadays, synthetic polymers are used in almost all walks of life. Modern society would look very different without them. The spreading of polymer use is connected to their unique properties: low density, low cost, good thermal/electrical insulation properties, high resistance to corrosion, low-energy demanding polymer manufacture and facile processing into final products. For a given application, the properties of a polymer can be tuned or enhanced by combination with other materials, as in composites. Their application allows to save energy (lighter cars and planes, thermally insulated buildings), protect food and drinking water (packaging), save land and lower use of fertilizers (synthetic fibres), preserve other materials (coatings), protect and save lives (hygiene, medical applications). A representative, non-exhaustive list of applications is given below.

- Clothing, sportswear and accessories: polyester and PVC clothing, spandex, sport shoes, wetsuits, footballs and billiard balls, skis and snowboards, rackets, parachutes, sails, tents and shelters.

- Electronic and photonic technologies: organic field effect transistors (OFET), light emitting diodes (OLED) and solar cells, television components, compact discs (CD), photoresists, holography.

- Packaging and containers: films, bottles, food packaging, barrels.

- Insulation: electrical and thermal insulation, spray foams.

- Construction and structural applications: garden furniture, PVC windows, flooring, sealing, pipes.

- Paints, glues and lubricants: varnish, adhesives, dispersants, anti-graffiti coatings, antifouling coatings, non-stick surfaces, lubricants.

- Car parts: tires, bumpers, windshields, windscreen wipers, fuel tanks, car seats.

- Household items: buckets, kitchenware, toys (e.g., construction sets and Rubik's Cube).

- Medical applications: blood bag, syringes, rubber gloves, surgical suture, contact lenses, prosthesis, controlled drug delivery and release, matrices for cell growth.

- Personal hygiene and healthcare: diapers using superabsorbent polymers, toothbrushes, cosmetics, shampoo, condoms.

- Security: personal protective equipment, bulletproof vests, space suits, ropes.

- Separation technologies: synthetic membranes, fuel cell membranes, filtration, ion-exchange resins.

- Money: polymer banknotes and payment cards.

- 3D printing.

Standardized nomenclature

[edit]There are multiple conventions for naming polymer substances. Many commonly used polymers, such as those found in consumer products, are referred to by a common or trivial name. The trivial name is assigned based on historical precedent or popular usage rather than a standardized naming convention. Both the American Chemical Society (ACS)[57] and IUPAC[58] have proposed standardized naming conventions; the ACS and IUPAC conventions are similar but not identical.[59] Examples of the differences between the various naming conventions are given in the table below:

| Common name | ACS name | IUPAC name |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene oxide) or PEO | Poly(oxyethylene) | Poly(oxyethylene) |

| Poly(ethylene terephthalate) or PET | Poly(oxy-1,2-ethanediyloxycarbonyl-1,4-phenylenecarbonyl) | Poly(oxyethyleneoxyterephthaloyl) |

| Nylon 6 or Polyamide 6 | Poly[imino(1-oxo-1,6-hexanediyl)] | Poly[azanediyl(1-oxohexane-1,6-diyl)] |

In both standardized conventions, the polymers' names are intended to reflect the monomer(s) from which they are synthesized (source based nomenclature) rather than the precise nature of the repeating subunit. For example, the polymer synthesized from the simple alkene ethene is called polyethene, retaining the -ene suffix even though the double bond is removed during the polymerization process:

However, IUPAC structure based nomenclature is based on naming of the preferred constitutional repeating unit.[60]

IUPAC has also issued guidelines for abbreviating new polymer names.[61] 138 common polymer abbreviations are also standardized in the standard ISO 1043–1.[62]

Characterization

[edit]Polymer characterization spans many techniques for determining the chemical composition, molecular weight distribution, and physical properties. Select common techniques include the following:

- Size-exclusion chromatography (also called gel permeation chromatography), sometimes coupled with static light scattering, can used to determine the number-average molecular weight, weight-average molecular weight, and dispersity.

- Scattering techniques, such as static light scattering and small-angle neutron scattering, are used to determine the dimensions (radius of gyration) of macromolecules in solution or in the melt. These techniques are also used to characterize the three-dimensional structure of microphase-separated block polymers, polymeric micelles, and other materials.

- Wide-angle X-ray scattering (also called wide-angle X-ray diffraction) is used to determine the crystalline structure of polymers (or lack thereof).

- Spectroscopy techniques, including Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, can be used to determine the chemical composition.

- Differential scanning calorimetry is used to characterize the thermal properties of polymers, such as the glass-transition temperature, crystallization temperature, and melting temperature. The glass-transition temperature can also be determined by dynamic mechanical analysis.

- Thermogravimetry is a useful technique to evaluate the thermal stability of the polymer.

- Rheology is used to characterize the flow and deformation behavior. It can be used to determine the viscosity, modulus, and other rheological properties. Rheology is also often used to determine the molecular architecture (molecular weight, molecular weight distribution, branching) and to understand how the polymer can be processed.

Degradation

[edit]

Polymer degradation is a change in the properties—tensile strength, color, shape, or molecular weight—of a polymer or polymer-based product under the influence of one or more environmental factors, such as heat, light, and the presence of certain chemicals, oxygen, and enzymes. This change in properties is often the result of bond breaking in the polymer backbone (chain scission) which may occur at the chain ends or at random positions in the chain.

Although such changes are frequently undesirable, in some cases, such as biodegradation and recycling, they may be intended to prevent environmental pollution. Degradation can also be useful in biomedical settings. For example, a copolymer of polylactic acid and polyglycolic acid is employed in hydrolysable stitches that slowly degrade after they are applied to a wound.

The susceptibility of a polymer to degradation depends on its structure. Epoxies and chains containing aromatic functionalities are especially susceptible to UV degradation while polyesters are susceptible to degradation by hydrolysis. Polymers containing an unsaturated backbone degrade via ozone cracking. Carbon based polymers are more susceptible to thermal degradation than inorganic polymers such as polydimethylsiloxane and are therefore not ideal for most high-temperature applications.[citation needed]

The degradation of polyethylene occurs by random scission—a random breakage of the bonds that hold the atoms of the polymer together. When heated above 450 °C, polyethylene degrades to form a mixture of hydrocarbons. In the case of chain-end scission, monomers are released and this process is referred to as unzipping or depolymerization. Which mechanism dominates will depend on the type of polymer and temperature; in general, polymers with no or a single small substituent in the repeat unit will decompose via random-chain scission.

The sorting of polymer waste for recycling purposes may be facilitated by the use of the resin identification codes developed by the Society of the Plastics Industry to identify the type of plastic.

Product failure

[edit]

Failure of safety-critical polymer components can cause serious accidents, such as fire in the case of cracked and degraded polymer fuel lines. Chlorine-induced cracking of acetal resin plumbing joints and polybutylene pipes has caused many serious floods in domestic properties, especially in the US in the 1990s. Traces of chlorine in the water supply attacked polymers present in the plumbing, a problem which occurs faster if any of the parts have been poorly extruded or injection molded. Attack of the acetal joint occurred because of faulty molding, leading to cracking along the threads of the fitting where there is stress concentration.

Polymer oxidation has caused accidents involving medical devices. One of the oldest known failure modes is ozone cracking caused by chain scission when ozone gas attacks susceptible elastomers, such as natural rubber and nitrile rubber. They possess double bonds in their repeat units which are cleaved during ozonolysis. Cracks in fuel lines can penetrate the bore of the tube and cause fuel leakage. If cracking occurs in the engine compartment, electric sparks can ignite the gasoline and can cause a serious fire. In medical use degradation of polymers can lead to changes of physical and chemical characteristics of implantable devices.[63]

Nylon 66 is susceptible to acid hydrolysis, and in one accident, a fractured fuel line led to a spillage of diesel into the road. If diesel fuel leaks onto the road, accidents to following cars can be caused by the slippery nature of the deposit, which is like black ice. Furthermore, the asphalt concrete road surface will suffer damage as a result of the diesel fuel dissolving the asphaltenes from the composite material, this resulting in the degradation of the asphalt surface and structural integrity of the road.

History

[edit]Polymers have been essential components of commodities since the early days of humankind. The use of wool (keratin), cotton and linen fibres (cellulose) for garments, paper reed (cellulose) for paper are just a few examples of how ancient societies exploited polymer-containing raw materials to obtain artefacts. The latex sap of "caoutchouc" trees (natural rubber) reached Europe in the 16th century from South America long after the Olmec, Maya and Aztec had started using it as a material to make balls, waterproof textiles and containers.[64]

The chemical manipulation of polymers dates back to the 19th century, although at the time the nature of these species was not understood. The behaviour of polymers was initially rationalised according to the theory proposed by Thomas Graham which considered them as colloidal aggregates of small molecules held together by unknown forces.

Notwithstanding the lack of theoretical knowledge, the potential of polymers to provide innovative, accessible and cheap materials was immediately grasped. The work carried out by Braconnot, Parkes, Ludersdorf, Hayward and many others on the modification of natural polymers determined many significant advances in the field.[65] Their contributions led to the discovery of materials such as celluloid, galalith, parkesine, rayon, vulcanised rubber and, later, Bakelite: all materials that quickly entered industrial manufacturing processes and reached households as garments components (e.g., fabrics, buttons), crockery and decorative items.

In 1920, Hermann Staudinger published his seminal work "Über Polymerisation",[66] in which he proposed that polymers were in fact long chains of atoms linked by covalent bonds. His work was debated at length, but eventually it was accepted by the scientific community. Because of this work, Staudinger was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1953.[67]

After the 1930s polymers entered a golden age during which new types were discovered and quickly given commercial applications, replacing naturally-sourced materials. This development was fuelled by an industrial sector with a strong economic drive and it was supported by a broad academic community that contributed innovative syntheses of monomers from cheaper raw material, more efficient polymerisation processes, improved techniques for polymer characterisation and advanced, theoretical understanding of polymers.[65]

Since 1953, six Nobel prizes have been awarded in the area of polymer science, excluding those for research on biological macromolecules. This further testifies to its impact on modern science and technology. As Lord Todd summarised in 1980, "I am inclined to think that the development of polymerization is perhaps the biggest thing that chemistry has done, where it has had the biggest effect on everyday life".[69]

See also

[edit]- Ideal chain

- Catenation

- Inorganic polymer

- Important publications in polymer chemistry

- Oligomer

- Polymer adsorption

- Polymer classes

- Polymer engineering

- Polymery (botany)

- Reactive compatibilization

- Sequence-controlled polymer

- Shape-memory polymer

- Sol–gel process

- Supramolecular polymer

- Thermoplastic

- Thermosetting polymer

References

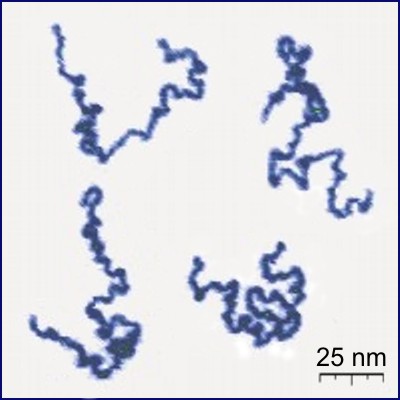

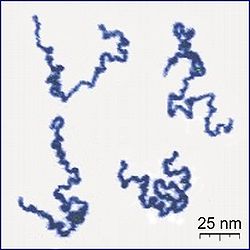

[edit]- ^ Roiter, Y.; Minko, S. (2005). "AFM Single Molecule Experiments at the Solid-Liquid Interface: In Situ Conformation of Adsorbed Flexible Polyelectrolyte Chains". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (45): 15688–15689. doi:10.1021/ja0558239. PMID 16277495.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "polymer". doi:10.1351/goldbook.P04735

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "macromolecule (polymer molecule)". doi:10.1351/goldbook.M03667

- ^ "Polymer – Definition of polymer". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ "Define polymer". Dictionary Reference. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ "Polymer on Britannica". 25 December 2023.

- ^ Painter, Paul C.; Coleman, Michael M. (1997). Fundamentals of polymer science: an introductory text. Lancaster, Pa.: Technomic Pub. Co. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-56676-559-6.

- ^ McCrum, N. G.; Buckley, C. P.; Bucknall, C. B. (1997). Principles of polymer engineering. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-856526-0.

- ^ If two substances had molecular formulae such that one was an integer multiple of the other – e.g., acetylene (C2H2) and benzene (C6H6) – Berzelius called the multiple formula "polymeric". See: Jöns Jakob Berzelius (1833) "Isomerie, Unterscheidung von damit analogen Verhältnissen" (Isomeric, distinction from relations analogous to it), Jahres-Bericht über die Fortschitte der physischen Wissenschaften …, 12: 63–67. From page 64: "Um diese Art von Gleichheit in der Zusammensetzung, bei Ungleichheit in den Eigenschaften, bezeichnen zu können, möchte ich für diese Körper die Benennung polymerische (von πολυς mehrere) vorschlagen." (In order to be able to denote this type of similarity in composition [which is accompanied] by differences in properties, I would like to propose the designation "polymeric" (from πολυς, several) for these substances.)

Originally published in 1832 in Swedish as: Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1832) "Isomeri, dess distinktion från dermed analoga förhållanden," Årsberättelse om Framstegen i Fysik och Kemi, pages 65–70; the word "polymeriska" appears on page 66. - ^ Jensen, William B. (2008). "Ask the Historian: The origin of the polymer concept" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 85 (5): 624–625. Bibcode:2008JChEd..85..624J. doi:10.1021/ed085p624. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Staudinger, H (1920). "Über Polymerisation" [On polymerization]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 53 (6): 1073–1085. doi:10.1002/cber.19200530627.

- ^ Allcock, Harry R.; Lampe, Frederick W.; Mark, James E. (2003). Contemporary Polymer Chemistry (3 ed.). Pearson Education. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-13-065056-6.

- ^ McGeoch, J.E.M.; McGeoch, M.W. (2015). "Polymer amide in the Allende and Murchison meteorites". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 50 (12): 1971–1983. Bibcode:2015M&PS...50.1971M. doi:10.1111/maps.12558. S2CID 97089690.

- ^ McGeogh, Julie E. M.; McGeogh, Malcolm W. (28 September 2022). "Chiral 480nm absorption in the hemoglycin space polymer: a possible link to replication". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 16198. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-21043-4. PMC 9519966. PMID 36171277.

- ^ Staff (29 June 2021). "Polymers in meteorites provide clues to early solar system". Science Digest. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "World Plastics Production" (PDF).

- ^ Sperling, L. H. (Leslie Howard) (2006). Introduction to physical polymer science. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-471-70606-9.

- ^ Sperling, p. 11

- ^ Sperling, p. 15

- ^ Sperling, p. 29

- ^ Bower, David I. (2002). An introduction to polymer physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-80128-0.

- ^ Rudin, p. 17

- ^ Cowie, p. 4

- ^ Sperling, p. 30

- ^ a b Rubinstein, Michael; Colby, Ralph H. (2003). Polymer physics. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-852059-7.

- ^ McCrum, p. 30

- ^ Rubinstein, p. 3

- ^ McCrum, p. 33

- ^ Rubinstein, pp. 23–24

- ^ Painter, p. 22

- ^ De Gennes, Pierre Gilles (1979). Scaling concepts in polymer physics. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1203-5.

- ^ Rubinstein, p. 5

- ^ McCrum, p. 37

- ^ Introduction to Polymer Science and Chemistry: A Problem-Solving Approach By Manas Chanda

- ^ O'Driscoll, K.; Amin Sanayei, R. (July 1991). "Chain-length dependence of the glass transition temperature". Macromolecules. 24 (15): 4479–4480. Bibcode:1991MaMol..24.4479O. doi:10.1021/ma00015a038.

- ^ Pokrovskii, V. N. (2010). The Mesoscopic Theory of Polymer Dynamics. Springer Series in Chemical Physics. Vol. 95. Bibcode:2010mtpd.book.....P. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2231-8. ISBN 978-90-481-2230-1.

- ^ Edwards, S. F. (1967). "The statistical mechanics of polymerized material". Proceedings of the Physical Society. 92 (1): 9–16. Bibcode:1967PPS....92....9E. doi:10.1088/0370-1328/92/1/303.

- ^ Painter, p. 14

- ^ a b c d Rudin, p. 18–20

- ^ a b c Cowie, p. 104

- ^ "Periodic copolymer". IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book"). International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 2014. doi:10.1351/goldbook.P04494. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Painter, p. 15

- ^ Sperling, p. 47

- ^ Lutz, Jean-François; Ouchi, Makoto; Liu, David R.; Sawamoto, Mitsuo (9 August 2013). "Sequence-Controlled Polymers". Science. 341 (6146) 1238149. doi:10.1126/science.1238149. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23929982. S2CID 206549042.

- ^ a b Bernd Tieke: Makromolekulare Chemie. 3. Auflage, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim 2014, S. 295f (in German).

- ^ a b Wolfgang Kaiser: Kunststoffchemie für Ingenieure. 3. Auflage, Carl Hanser, München 2011, S. 84.

- ^ Allcock, Harry R.; Lampe, Frederick W.; Mark, James E. (2003). Contemporary Polymer Chemistry (3 ed.). Pearson Education. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-13-065056-6.

- ^ Rubinstein, p. 13

- ^ Ashby, Michael; Jones, David (1996). Engineering Materials (2 ed.). Butterworth-Heinermann. pp. 191–195. ISBN 978-0-7506-2766-5.

- ^ Meyers, M. A.; Chawla, K. K. (1999). Mechanical Behavior of Materials. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-521-86675-0. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ Fried, Joel R. (2003). Polymer Science & Technology (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 155–6. ISBN 0-13-018168-4.

- ^ Brandrup, J.; Immergut, E.H.; Grulke, E.A. (1999). Polymer Handbook (4 ed.). Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-47936-9.

- ^ Meille, S.; Allegra, G.; Geil, P.; et al. (2011). "Definitions of terms relating to crystalline polymers (IUPAC Recommendations 2011)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 83 (10): 1831–1871. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-11-13. S2CID 98823962. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ Capponi, S.; Alvarez, F.; Racko, D. (2020), "Free Volume in a PVME Polymer–Water Solution", Macromolecules, XXX (XXX): XXX–XXX, Bibcode:2020MaMol..53.4770C, doi:10.1021/acs.macromol.0c00472, hdl:10261/218380, S2CID 219911779

- ^ Duarte, F. J. (1999). "Multiple-prism grating solid-state dye laser oscillator: optimized architecture". Applied Optics. 38 (30): 6347–6349. Bibcode:1999ApOpt..38.6347D. doi:10.1364/AO.38.006347. PMID 18324163.

- ^ Duarte, F. J. (2003). Tunable Laser Optics. New York: Elsevier Academic. ISBN 978-0-12-222696-0.

- ^ CAS: Index Guide, Appendix IV ((c) 1998)

- ^ IUPAC (1976). "Nomenclature of Regular Single-Strand Organic Polymers". Pure Appl. Chem. 48 (3): 373–385. doi:10.1351/pac197648030373.

- ^ Wilks, E.S. "Macromolecular Nomenclature Note No. 18". Archived from the original on 25 September 2003.

- ^ Hiorns, R. C.; Boucher, R. J.; Duhlev, R.; Hellwich, Karl-Heinz; Hodge, Philip; Jenkins, Aubrey D.; Jones, Richard G.; Kahovec, Jaroslav; Moad, Graeme; Ober, C. K.; Smith, D. W. (3 October 2012). "A brief guide to polymer nomenclature (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 84 (10): 2167–2169. doi:10.1351/PAC-REP-12-03-05. ISSN 0033-4545. S2CID 95629051.

- ^ He, Jiasong; Chen, Jiazhong; Hellwich, Karl-Heinz; Hess, Michael; Horie, Kazuyuki; Jones, Richard G.; Kahovec, Jaroslav; Kitayama, Tatsuki; Kratochvíl, Pavel; Meille, Stefano V.; Mita, Itaru; Santos, Claudio dos; Vert, Michel; Vohlídal, Jiří (18 June 2014). "Abbreviations of polymer names and guidelines for abbreviating polymer names (IUPAC Recommendations 2014)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 86 (6): 1003–1015. doi:10.1515/pac-2012-1203. hdl:11311/1022322. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ "ISO 1043-1:2011". ISO. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Iakovlev, V.; Guelcher, S.; Bendavid, R. (28 August 2015). "Degradation of polypropylene in vivo: A microscopic analysis of meshes explanted from patients". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 105 (2): 237–248. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.33502. PMID 26315946.

- ^ Hurley, Paul E. (May 1981). "History of Natural Rubber". Journal of Macromolecular Science: Part A - Chemistry. 15 (7): 1279–1287. doi:10.1080/00222338108056785. ISSN 0022-233X.

- ^ a b Feldman, Dorel (January 2008). "Polymer History". Designed Monomers and Polymers. 11 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1163/156855508X292383. ISSN 1568-5551. S2CID 219539020.

- ^ Staudinger, H. (12 June 1920). "Über Polymerisation". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series). 53 (6): 1073–1085. doi:10.1002/cber.19200530627. ISSN 0365-9488.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1953". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Feldman, Dorel (1 January 2008). "Polymer History". Designed Monomers and Polymers. 11 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1163/156855508X292383. S2CID 219539020.

- ^ "Lord Todd: the state of chemistry". Chemical & Engineering News Archive. 58 (40): 28–33. 6 October 1980. doi:10.1021/cen-v058n040.p028. ISSN 0009-2347.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cowie, J. M. G. (John McKenzie Grant) (1991). Polymers: chemistry and physics of modern materials. Glasgow: Blackie. ISBN 978-0-412-03121-2.

- Hall, Christopher (1989). Polymer materials (PDF) (2nd ed.). London; New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-46379-6.

- Rudin, Alfred (1982). The elements of polymer science and engineering. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-601680-2.

- Wright, David C. (2001). Environmental Stress Cracking of Plastics. RAPRA. ISBN 978-1-85957-064-7.

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2021) |

Polymer

View on GrokipediaEtymology and History

Etymology

The term "polymer" originates from the Greek words poly (πολύς), meaning "many," and meros (μέρος), meaning "parts," and was coined in 1833 by the Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius to describe compounds sharing the same empirical composition but differing in molecular weight by integral multiples, such as ethylene and butylene.[6] Berzelius introduced this terminology in the context of organic chemistry to denote a specific type of isomerism, without implying the long-chain structures understood today.[6] In 1861, British chemist Thomas Graham extended the term "polymer" to describe colloidal substances, proposing that materials like starch and gelatin were aggregates or "polymeric" associations of smaller molecules held together by weak forces, as part of his association theory contrasting colloids with crystalloids.[7] This usage marked an early application to high-molecular-weight substances exhibiting low diffusivity, laying groundwork for later interpretations in macromolecular chemistry.[7] The concept evolved significantly in the early 20th century through the work of Hermann Staudinger, who in the 1920s advocated for the macromolecular hypothesis, redefining polymers as long-chain molecules formed by covalent linkages of monomeric units rather than mere aggregates.[6] Staudinger coined the term "macromolecule" (Makromolekül) in 1922 to emphasize the enormous size of these structures, distinguishing them from Berzelius's original compositional sense and Graham's colloidal view.[7] These developments solidified "polymer" in its modern sense, focusing on chain-like macromolecules central to both natural and synthetic materials.[6]Historical Development

The utilization of natural polymers dates back to ancient civilizations. In China, around 2700 BCE, the production of silk—a protein-based polymer derived from silkworm cocoons—emerged as a key technological achievement, enabling the weaving of fine fabrics that became central to trade and culture.[8] Similarly, in Mesoamerica, by 1600 BCE, indigenous peoples such as the Olmec and Maya processed latex from the Castilla elastica tree, mixing it with morning glory vine juice to create solid rubber for balls, seals, and other tools, demonstrating early mastery of natural polymer manipulation.[9] The 19th century marked the transition toward synthetic polymers through industrial innovations. In 1839, American inventor Charles Goodyear discovered vulcanization, a process that heated natural rubber with sulfur to enhance its elasticity and durability, revolutionizing its commercial viability for tires and footwear.[10] Two decades later, in 1862, British chemist Alexander Parkes patented Parkesine, the first man-made plastic derived from cellulose nitrate, which could be molded into durable items like combs and buttons, laying the groundwork for the plastics industry.[11] In 1907, Belgian-American chemist Leo Baekeland invented Bakelite, the first fully synthetic plastic, through the condensation of phenol and formaldehyde, initiating the era of commercial thermosetting plastics.[12] The 20th century saw foundational scientific breakthroughs that established polymer science as a distinct field. In 1920, German chemist Hermann Staudinger proposed the macromolecular hypothesis, arguing that polymers consist of long chains of covalently bonded monomers rather than aggregates of small molecules, a concept validated over decades and earning him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953.[13] Building on this, in 1935, American chemist Wallace Carothers at DuPont synthesized nylon, the first fully synthetic fiber, by polycondensing adipic acid and hexamethylenediamine, enabling mass production of strong, versatile materials for textiles and more.[14] In the 1950s, Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta developed Ziegler-Natta catalysts, enabling stereospecific polymerization of olefins like ethylene and propylene into high-density polyethylene and isotactic polypropylene, innovations recognized with the 1963 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[15] Entering the 21st century, polymer research shifted toward functional and sustainable materials. In 2000, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Alan J. Heeger, Alan G. MacDiarmid, and Hideki Shirakawa for discovering conductive polymers, such as doped polyacetylene, which conduct electricity like metals while retaining polymer flexibility, opening applications in electronics and sensors.[16] In the 2020s, attention has intensified on biodegradable polymers like polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), microbial polyesters that fully degrade in natural environments, addressing plastic waste through sustainable alternatives in packaging and agriculture.[17] By 2025, advancements in bio-based polymers from renewable feedstocks, such as sugarcane-derived polyethylene and CO2-captured materials, have accelerated, with companies like Braskem introducing innovations for reusable packaging and construction, driven by circular economy demands.[18]Classification and Examples

Natural Polymers

Natural polymers, also known as biopolymers, are large molecules synthesized by living organisms through enzymatic processes, consisting of repeating monomeric units covalently linked to form chains or networks.[19] These include three primary classes: proteins, formed from amino acid monomers; nucleic acids, composed of nucleotide units such as in DNA and RNA; and polysaccharides, built from sugar monomers.[20] Unlike synthetic polymers, biopolymers are produced in biological systems and play essential roles in cellular structure, function, and metabolism.[21] Prominent examples derive from diverse biological sources, with plants serving as the primary origin for many abundant polysaccharides. Cellulose, a linear polysaccharide of glucose units linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, is the most prevalent organic polymer on Earth, accounting for approximately 33% of all plant biomass and forming the structural framework of plant cell walls.[22][23] Starch, another plant-derived polysaccharide composed of α-glucose units, functions mainly in energy storage in seeds, roots, and tubers.[24] In animals, proteins such as collagen predominate; collagen is a fibrous protein assembled from glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline-rich sequences, forming a triple helix that provides tensile strength in connective tissues like skin, tendons, and bones.[25] Nucleic acids originate from all living cells, with DNA serving as the genetic blueprint in nuclei and RNA facilitating protein synthesis.[26] Chitin, a polysaccharide of N-acetylglucosamine, forms the exoskeletons of arthropods and fungal cell walls.[20] Natural rubber, a polyisoprene elastomer, is extracted from the latex of the Hevea brasiliensis tree, where it exists as colloidal particles in the sap.[27] Lignin, a complex aromatic heteropolymer derived from phenylpropanoid units, impregnates plant cell walls, particularly in wood, contributing up to one-third of its dry weight.[28] In nature, these polymers fulfill critical structural, storage, and informational roles. Cellulose and lignin provide mechanical support and rigidity to plant tissues, enabling upright growth and resistance to environmental stresses.[29] Starch and glycogen (an animal analog) act as energy reserves, broken down into glucose during metabolic needs.[30] Proteins like collagen maintain tissue integrity and elasticity in animal extracellular matrices, while enzymes (also proteins) catalyze biochemical reactions.[31] Nucleic acids store and transmit hereditary information, with DNA's double-helix structure ensuring stable replication and RNA enabling gene expression.[21] Chitin offers protective barriers in invertebrates and fungi, and natural rubber in plants may deter herbivores or seal wounds.[32] These functions underscore the evolutionary adaptation of biopolymers to sustain life processes across kingdoms.Synthetic Polymers

Synthetic polymers are human-made materials produced through chemical synthesis in laboratories, typically derived from petroleum-based or bio-based monomers such as ethylene or lactic acid.[33][34] Unlike natural polymers like cellulose or proteins, which occur in biological systems, synthetic polymers offer greater versatility in structure and properties due to controlled manufacturing processes.[35] These polymers are broadly classified into major categories based on their thermal and mechanical behaviors: thermoplastics, thermosets, and elastomers. Thermoplastics, which soften upon heating and can be reshaped repeatedly, include polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride (PVC); for instance, high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) are widely used in packaging due to their durability and flexibility.[36] Thermosets, such as epoxy resins, form irreversible cross-linked networks during curing, resulting in rigid structures with high thermal stability suitable for adhesives and composites.[37] Elastomers, characterized by high elasticity and resilience, encompass synthetic rubbers like styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR), which mimics the properties of natural rubber but offers improved resistance to abrasion and aging.[38] Prominent examples highlight the diversity of synthetic polymers. Polystyrene serves as a lightweight foam material for insulation and packaging, valued for its low cost and ease of molding.[39] Polyurethanes, formed from diisocyanates and polyols, are employed in flexible foams for cushions and durable coatings for surfaces, providing a balance of toughness and elasticity.[40] A notable bio-derived addition is polylactic acid (PLA), an aliphatic polyester produced from renewable sources like corn starch, which was commercialized in the early 1990s and is prized for its biodegradability and use in packaging and medical applications.[41][42] The design of synthetic polymers emphasizes tailoring molecular architecture to achieve targeted properties, such as enhanced durability through cross-linking or flexibility via linear chain structures. By selecting specific monomers, adjusting molecular weight, and controlling polymerization conditions, engineers customize these materials for applications requiring precise mechanical, thermal, or chemical performance.[43] This intentional engineering distinguishes synthetic polymers, enabling innovations beyond the limitations of natural counterparts.Molecular Structure

Monomers and Repeat Units

Polymers are formed from small organic molecules known as monomers, which are capable of linking together through chemical reactions to create long chains or networks.[44] A monomer typically contains functional groups that enable polymerization, such as double bonds in vinyl monomers or reactive end groups in bifunctional molecules. For instance, ethylene (C₂H₄), a simple alkene, serves as the monomer for polyethylene, one of the most common synthetic polymers.[44] In biological systems, amino acids act as monomers, linking to form proteins; each amino acid has an amino group and a carboxyl group that participate in bond formation.[45] Upon polymerization, monomers are incorporated into the polymer chain, resulting in a repeating structural segment called the constitutional repeating unit (CRU), which is the smallest identifiable repeating portion of the polymer backbone.[44] The CRU is determined by examining the polymer's connectivity and selecting the subunit that, when repeated, reconstructs the chain with the lowest possible locants for substituents. For polyethylene, the CRU is , derived directly from the ethylene monomer after opening its double bond.[44] In proteins, the CRU consists of the amide-linked backbone from amino acids, excluding the variable side chains.[45] The linkages between monomers occur via covalent bonds formed in two primary mechanisms: polyaddition and polycondensation. In polyaddition, monomers react without eliminating small molecules, directly incorporating the entire monomer structure into the repeat unit; this is common for monomers with carbon-carbon double bonds, as in the formation of polyethylene from ethylene.[46] In polycondensation, monomers link with the release of a small byproduct, such as water, resulting in a repeat unit that may differ slightly from the original monomer; for example, amino acids form peptide bonds in proteins by eliminating H₂O from the carboxyl and amino groups.[46][45] The general representation of polymerization is , where denotes the monomer and is the degree of polymerization, indicating the number of repeat units in the chain.[46] Polymers are classified as homopolymers or copolymers based on the number of distinct monomer types. Homopolymers consist of a single repeating monomer type, such as polyethylene derived solely from ethylene, leading to a uniform CRU throughout the chain.[44] Copolymers, in contrast, incorporate two or more different monomers, resulting in sequences of varied repeat units; nomenclature often uses connectives like "co-" to denote this, as in poly(styrene-co-butadiene).[44] This distinction allows for tailored properties in materials design.Microstructure

The microstructure of polymers refers to the arrangement and configuration of monomer units within the polymer chains, which significantly influences their physical and chemical behavior. Polymer architecture encompasses various structural motifs, including linear, branched, cross-linked, star, and dendrimer forms. In linear polymers, monomer units connect in a straight chain without side branches, as seen in high-density polyethylene. Branched architectures feature side chains attached to the main backbone, such as in low-density polyethylene produced via free-radical polymerization, where short-chain branches arise from intramolecular hydrogen abstraction during synthesis. Cross-linked polymers involve covalent bonds between different chains, forming networks that enhance rigidity, while star polymers consist of multiple linear arms radiating from a central core, and dendrimers exhibit highly ordered, tree-like branching with precise generational layers. These architectures are tailored through synthesis methods to achieve desired properties, with branching generally increasing chain entanglement and altering flow characteristics.[47][48][49] Chain length in polymers is quantified by molecular weight metrics, reflecting the degree of polymerization. The number-average molecular weight () is the arithmetic mean of the molecular weights of all chains, calculated as the total mass divided by the number of molecules, while the weight-average molecular weight () weights each chain by its mass, emphasizing longer chains and typically yielding higher values than . The polydispersity index (PDI), defined as: measures the breadth of the molecular weight distribution; a PDI of 1 indicates monodispersity (uniform chain lengths), but most synthetic polymers have PDI > 1, signifying a distribution of lengths that broadens with less controlled polymerization, thereby increasing melt viscosity and processing challenges. These parameters are determined experimentally via techniques like gel permeation chromatography.[50][51] Copolymers, formed from two or more distinct monomers, exhibit varied microstructures based on monomer sequencing. Random copolymers have monomers distributed irregularly along the chain, leading to averaged properties; alternating copolymers feature strict ABAB patterns, often due to charge-transfer interactions in copolymerization; block copolymers consist of long sequences of one monomer type followed by another (e.g., AAAAABBBB), enabling phase separation into domains; and graft copolymers attach branches of one monomer type onto a backbone of another. For instance, block copolymers can self-assemble into ordered structures like micelles in selective solvents due to incompatible blocks. These configurations are controlled by polymerization techniques such as living anionic polymerization for blocks.[52][53] Tacticity describes the stereochemical arrangement of substituents along the polymer backbone in vinyl polymers, arising from the chirality at each repeat unit. Isotactic polymers have all substituents on the same side of the chain (regular configuration), syndiotactic polymers alternate sides, and atactic polymers show random placement, resulting in amorphous structures. Stereoregular isotactic and syndiotactic polymers, which enable higher order, are synthesized using Ziegler-Natta catalysts—heterogeneous systems of transition metal compounds (e.g., TiCl₄) and organoaluminum cocatalysts—that coordinate monomers in a specific orientation during propagation, as pioneered in the 1950s for polypropene production. This stereocontrol revolutionized polyolefin synthesis, allowing crystalline materials with enhanced strength.[54][55]Morphology

Polymer morphology refers to the physical arrangement and organization of polymer chains in bulk materials, which determines many macroscopic properties such as mechanical strength and optical clarity. In amorphous regions, polymer chains typically adopt random coil conformations, characterized by disordered, entangled structures that maximize entropy, as described in Flory's statistical model of real polymer chains.[56] In contrast, within crystalline domains, chains assume more ordered conformations, such as extended planar zigzags in polyethylene or helical arrangements in isotactic polymers like polypropylene, enabling close packing and higher density.[57] Crystallinity represents the degree of structural order in these crystalline domains, often quantified as the percentage of crystalline material relative to the total mass, with typical values ranging from 50% to 90% in high-density polyethylene (HDPE).[58] This degree is commonly measured using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), where the heat of fusion is compared to that of a fully crystalline reference.[59] Spherulites serve as the primary growth units in semicrystalline polymers, forming radially branching aggregates of lamellar crystals from a central nucleus, as explained by the phenomenological theory of Keith and Padden, which attributes their development to the diffusion of noncrystallizing material ahead of the crystallization front.[60] Semicrystalline polymers consist of alternating crystalline and amorphous regions, while fully amorphous polymers lack long-range order. In the amorphous components of both types, the material exists in a glassy state below the glass transition temperature (Tg), where chains are rigid and immobile due to restricted segmental motion, transitioning to a rubbery state above Tg with increased chain flexibility and elasticity.[61] The degree of crystallinity is also influenced by the tacticity of the polymer chains, as detailed in the microstructure section. Morphology is significantly affected by processing conditions, such as cooling rate during solidification. For instance, rapid quenching of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) at rates of 1 K/s or higher yields a fully amorphous structure by preventing chain reorganization into crystals, whereas slower cooling promotes partial or full crystallization.[62]Synthesis

Polymerization Mechanisms