Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

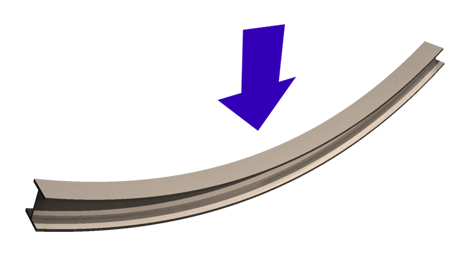

Bending

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Continuum mechanics |

|---|

In applied mechanics, bending (also known as flexure) characterizes the behavior of a slender structural element subjected to an external load applied perpendicularly to a longitudinal axis of the element.

The structural element is assumed to be such that at least one of its dimensions is a small fraction, typically 1/10 or less, of the other two.[1] When the length is considerably longer than the width and the thickness, the element is called a beam. For example, a closet rod sagging under the weight of clothes on clothes hangers is an example of a beam experiencing bending. On the other hand, a shell is a structure of any geometric form where the length and the width are of the same order of magnitude but the thickness of the structure (known as the 'wall') is considerably smaller. A large diameter, but thin-walled, short tube supported at its ends and loaded laterally is an example of a shell experiencing bending.

In the absence of a qualifier, the term bending is ambiguous because bending can occur locally in all objects. Therefore, to make the usage of the term more precise, engineers refer to a specific object such as; the bending of rods,[2] the bending of beams,[1] the bending of plates,[3] the bending of shells[2] and so on.

Quasi-static bending of beams

[edit]A beam deforms and stresses develop inside it when a transverse load is applied on it. In the quasi-static case, the amount of bending deflection and the stresses that develop are assumed not to change over time. In a horizontal beam supported at the ends and loaded downwards in the middle, the material at the over-side of the beam is compressed while the material at the underside is stretched. There are two forms of internal stresses caused by lateral loads:

- Shear stress parallel to the lateral loading plus complementary shear stress on planes perpendicular to the load direction;

- Direct compressive stress in the upper region of the beam, applicable mostly to cement concreted elements and,

- Direct tensile stress, applicable to steel elements, and is at the lower region of the beam.

These last two forces form a couple or moment as they are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. This bending moment resists the sagging deformation characteristic of a beam experiencing bending. The stress distribution in a beam can be predicted quite accurately when some simplifying assumptions are used.[1]

Euler–Bernoulli bending theory

[edit]

In the Euler–Bernoulli theory of slender beams, a major assumption is that 'plane sections remain plane'. In other words, any deformation due to shear across the section is not accounted for (no shear deformation). Also, this linear distribution is only applicable if the maximum stress is less than the yield stress of the material. For stresses that exceed yield, refer to article plastic bending. At yield, the maximum stress experienced in the section (at the furthest points from the neutral axis of the beam) is defined as the flexural strength.

Consider beams where the following are true:

- The beam is originally straight and slender, and any taper is slight

- The material is isotropic (or orthotropic), linear elastic, and homogeneous across any cross section (but not necessarily along its length)

- Only small deflections are considered

In this case, the equation describing beam deflection () can be approximated as:

where the second derivative of its deflected shape with respect to is interpreted as its curvature, is the Young's modulus, is the area moment of inertia of the cross-section, and is the internal bending moment in the beam.

If, in addition, the beam is homogeneous along its length as well, and not tapered (i.e. constant cross section), and deflects under an applied transverse load , it can be shown that:[1]

This is the Euler–Bernoulli equation for beam bending.

After a solution for the displacement of the beam has been obtained, the bending moment () and shear force () in the beam can be calculated using the relations

Simple beam bending is often analyzed with the Euler–Bernoulli beam equation. The conditions for using simple bending theory are:[4]

- The beam is subject to pure bending. This means that the shear force is zero, and that no torsional or axial loads are present.

- The material is isotropic (or orthotropic) and homogeneous.

- The material obeys Hooke's law (it is linearly elastic and will not deform plastically).

- The beam is initially straight with a cross section that is constant throughout the beam length.

- The beam has an axis of symmetry in the plane of bending.

- The proportions of the beam are such that it would fail by bending rather than by crushing, wrinkling or sideways buckling.

- Cross-sections of the beam remain plane during bending.

Compressive and tensile forces develop in the direction of the beam axis under bending loads. These forces induce stresses on the beam. The maximum compressive stress is found at the uppermost edge of the beam while the maximum tensile stress is located at the lower edge of the beam. Since the stresses between these two opposing maxima vary linearly, there therefore exists a point on the linear path between them where there is no bending stress. The locus of these points is the neutral axis. Because of this area with no stress and the adjacent areas with low stress, using uniform cross section beams in bending is not a particularly efficient means of supporting a load as it does not use the full capacity of the beam until it is on the brink of collapse. Wide-flange beams (Ɪ-beams) and truss girders effectively address this inefficiency as they minimize the amount of material in this under-stressed region.

The classic formula for determining the bending stress in a beam under simple bending is:[5]

where

- is the bending stress

- – the moment about the neutral axis

- – the perpendicular distance to the neutral axis

- – the second moment of area about the neutral axis z.

- - the Resistance Moment about the neutral axis z.

Extensions of Euler-Bernoulli beam bending theory

[edit]Plastic bending

[edit]The equation is valid only when the stress at the extreme fiber (i.e., the portion of the beam farthest from the neutral axis) is below the yield stress of the material from which it is constructed. At higher loadings the stress distribution becomes non-linear, and ductile materials will eventually enter a plastic hinge state where the magnitude of the stress is equal to the yield stress everywhere in the beam, with a discontinuity at the neutral axis where the stress changes from tensile to compressive. This plastic hinge state is typically used as a limit state in the design of steel structures.

Complex or asymmetrical bending

[edit]The equation above is only valid if the cross-section is symmetrical. For homogeneous beams with asymmetrical sections, the maximum bending stress in the beam is given by

where are the coordinates of a point on the cross section at which the stress is to be determined as shown to the right, and are the bending moments about the y and z centroid axes, and are the second moments of area (distinct from moments of inertia) about the y and z axes, and is the product of moments of area. Using this equation it is possible to calculate the bending stress at any point on the beam cross section regardless of moment orientation or cross-sectional shape. Note that do not change from one point to another on the cross section.

Large bending deformation

[edit]

For large deformations of the body, the stress in the cross-section is calculated using an extended version of this formula. First the following assumptions must be made:

- Assumption of flat sections – before and after deformation the considered section of body remains flat (i.e., is not swirled).

- Shear and normal stresses in this section that are perpendicular to the normal vector of cross section have no influence on normal stresses that are parallel to this section.

Large bending considerations should be implemented when the bending radius is smaller than ten section heights h:

With those assumptions the stress in large bending is calculated as:

where

- is the normal force

- is the section area

- is the bending moment

- is the local bending radius (the radius of bending at the current section)

- is the area moment of inertia along the x-axis, at the place (see Steiner's theorem)

- is the position along y-axis on the section area in which the stress is calculated.

When bending radius approaches infinity and , the original formula is back:

- .

Timoshenko bending theory

[edit]

In 1921, Timoshenko improved upon the Euler–Bernoulli theory of beams by adding the effect of shear into the beam equation. The kinematic assumptions of the Timoshenko theory are:

- normals to the axis of the beam remain straight after deformation

- there is no change in beam thickness after deformation

However, normals to the axis are not required to remain perpendicular to the axis after deformation.

The equation for the quasistatic bending of a linear elastic, isotropic, homogeneous beam of constant cross-section beam under these assumptions is[7]

where is the area moment of inertia of the cross-section, is the cross-sectional area, is the shear modulus, is a shear correction factor, and is an applied transverse load. For materials with Poisson's ratios () close to 0.3, the shear correction factor for a rectangular cross-section is approximately

The rotation () of the normal is described by the equation

The bending moment () and the shear force () are given by

Beams on elastic foundations

[edit]According to Euler–Bernoulli, Timoshenko or other bending theories, the beams on elastic foundations can be explained. In some applications such as rail tracks, foundation of buildings and machines, ships on water, roots of plants etc., the beam subjected to loads is supported on continuous elastic foundations (i.e. the continuous reactions due to external loading is distributed along the length of the beam)[8][9][10][11]

Dynamic bending of beams

[edit]The dynamic bending of beams,[12] also known as flexural vibrations of beams, was first investigated by Daniel Bernoulli in the late 18th century. Bernoulli's equation of motion of a vibrating beam tended to overestimate the natural frequencies of beams and was improved marginally by Rayleigh in 1877 by the addition of a mid-plane rotation. In 1921 Stephen Timoshenko improved the theory further by incorporating the effect of shear on the dynamic response of bending beams. This allowed the theory to be used for problems involving high frequencies of vibration where the dynamic Euler–Bernoulli theory is inadequate. The Euler-Bernoulli and Timoshenko theories for the dynamic bending of beams continue to be used widely by engineers.

Euler–Bernoulli theory

[edit]The Euler–Bernoulli equation for the dynamic bending of slender, isotropic, homogeneous beams of constant cross-section under an applied transverse load is[7]

where is the Young's modulus, is the area moment of inertia of the cross-section, is the deflection of the neutral axis of the beam, and is mass per unit length of the beam.

Free vibrations

[edit]For the situation where there is no transverse load on the beam, the bending equation takes the form

Free, harmonic vibrations of the beam can then be expressed as

and the bending equation can be written as

The general solution of the above equation is

where are constants and

| The mode shapes of a cantilevered Ɪ-beam | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Timoshenko–Rayleigh theory

[edit]In 1877, Rayleigh proposed an improvement to the dynamic Euler–Bernoulli beam theory by including the effect of rotational inertia of the cross-section of the beam. Timoshenko improved upon that theory in 1922 by adding the effect of shear into the beam equation. Shear deformations of the normal to the mid-surface of the beam are allowed in the Timoshenko–Rayleigh theory.

The equation for the bending of a linear elastic, isotropic, homogeneous beam of constant cross-section under these assumptions is[7][13]

where is the polar moment of inertia of the cross-section, is the mass per unit length of the beam, is the density of the beam, is the cross-sectional area, is the shear modulus, and is a shear correction factor. For materials with Poisson's ratios () close to 0.3, the shear correction factor are approximately

Free vibrations

[edit]For free, harmonic vibrations the Timoshenko–Rayleigh equations take the form

This equation can be solved by noting that all the derivatives of must have the same form to cancel out and hence as solution of the form may be expected. This observation leads to the characteristic equation

The solutions of this quartic equation are

where

The general solution of the Timoshenko-Rayleigh beam equation for free vibrations can then be written as

Quasistatic bending of plates

[edit]

The defining feature of beams is that one of the dimensions is much larger than the other two. A structure is called a plate when it is flat and one of its dimensions is much smaller than the other two. There are several theories that attempt to describe the deformation and stress in a plate under applied loads two of which have been used widely. These are

- the Kirchhoff–Love theory of plates (also called classical plate theory)

- the Mindlin–Reissner plate theory (also called the first-order shear theory of plates)

Kirchhoff–Love theory of plates

[edit]The assumptions of Kirchhoff–Love theory are

- straight lines normal to the mid-surface remain straight after deformation

- straight lines normal to the mid-surface remain normal to the mid-surface after deformation

- the thickness of the plate does not change during a deformation.

These assumptions imply that

where is the displacement of a point in the plate and is the displacement of the mid-surface.

The strain-displacement relations are

The equilibrium equations are

where is an applied load normal to the surface of the plate.

In terms of displacements, the equilibrium equations for an isotropic, linear elastic plate in the absence of external load can be written as

In direct tensor notation,

Mindlin–Reissner theory of plates

[edit]The special assumption of this theory is that normals to the mid-surface remain straight and inextensible but not necessarily normal to the mid-surface after deformation. The displacements of the plate are given by

where are the rotations of the normal.

The strain-displacement relations that result from these assumptions are

where is a shear correction factor.

The equilibrium equations are

where

Dynamic bending of plates

[edit]Dynamics of thin Kirchhoff plates

[edit]The dynamic theory of plates determines the propagation of waves in the plates, and the study of standing waves and vibration modes. The equations that govern the dynamic bending of Kirchhoff plates are

where, for a plate with density ,

and

The figures below show some vibrational modes of a circular plate.

-

mode k = 0, p = 1

-

mode k = 0, p = 2

-

mode k = 1, p = 2

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Boresi, A. P. and Schmidt, R. J. and Sidebottom, O. M., 1993, Advanced mechanics of materials, John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- ^ a b Libai, A. and Simmonds, J. G., 1998, The nonlinear theory of elastic shells, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Timoshenko, S. and Woinowsky-Krieger, S., 1959, Theory of plates and shells, McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Shigley J, "Mechanical Engineering Design", p44, International Edition, pub McGraw Hill, 1986, ISBN 0-07-100292-8

- ^ Gere, J. M. and Timoshenko, S.P., 1997, Mechanics of Materials, PWS Publishing Company.

- ^ Cook and Young, 1995, Advanced Mechanics of Materials, Macmillan Publishing Company: New York

- ^ a b c Thomson, W. T., 1981, Theory of Vibration with Applications

- ^ HETÉNYI, Miklos (1946). Beams on Elastic Foundation. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Studies, USA.

- ^ MELERSKI, E., S. (2006). Design Analysis of Beams, Circular Plates and Cylindrical Tanks on Elastic Foundations (2nd ed.). London, UK: Taylor & Francis Group. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-415-38350-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ TSUDIK, E. Analysis of Beams and Frames on Elastic Foundation. USA: Trafford Publishing. p. 248. ISBN 1-4120-7950-0.

- ^ FRYDRÝŠEK, Karel; Tvrdá, Katarína; Jančo, Roland; et al. (2013). Handbook of Structures on Elastic Foundation (1st ed.). Ostrava, Czech Republic: VSB - Technical University of Ostrava. pp. 1–1691. ISBN 978-80-248-3238-8.

- ^ Han, S. M, Benaroya, H. and Wei, T., 1999, "Dynamics of transversely vibrating beams using four engineering theories," Journal of Sound and Vibration, vol. 226, no. 5, pp. 935–988.

- ^ Rosinger, H. E. and Ritchie, I. G., 1977, On Timoshenko's correction for shear in vibrating isotropic beams, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., vol. 10, pp. 1461–1466.

![{\displaystyle w(x,t)={\text{Re}}[{\hat {w}}(x)~e^{-i\omega t}]\quad \implies \quad {\cfrac {\partial ^{2}w}{\partial t^{2}}}=-\omega ^{2}~w(x,t)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7b17ad3e37e2553884da6fcb9dffd7487039774e)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&EI~{\frac {\partial ^{4}w}{\partial x^{4}}}+m~{\frac {\partial ^{2}w}{\partial t^{2}}}-\left(J+{\frac {EIm}{kAG}}\right){\frac {\partial ^{4}w}{\partial x^{2}~\partial t^{2}}}+{\frac {Jm}{kAG}}~{\frac {\partial ^{4}w}{\partial t^{4}}}\\[6pt]={}&q(x,t)+{\frac {J}{kAG}}~{\frac {\partial ^{2}q}{\partial t^{2}}}-{\frac {EI}{kAG}}~{\frac {\partial ^{2}q}{\partial x^{2}}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5b65d649cab51d29f4b0bb8e69a8bbccb9364b44)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}k&={\frac {5+5\nu }{6+5\nu }}\quad {\text{rectangular cross-section}}\\[6pt]&={\frac {6+12\nu +6\nu ^{2}}{7+12\nu +4\nu ^{2}}}\quad {\text{circular cross-section}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a8c11a187caa54d9696a9077b73e9bcd49ea0962)