Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

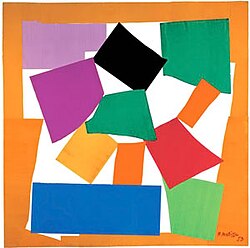

The Snail

View on Wikipedia| The Snail | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Henri Matisse |

| Year | 1953 |

| Type | Gouache on paper |

| Dimensions | 287 cm × 288 cm (112+3⁄4° in × 108 in) |

| Location | Tate Modern, London |

The Snail (L'escargot) is a collage by Henri Matisse. The work was created from summer 1952 to early 1953. It is pigmented with gouache on paper, cut with shears and pasted onto a base layer of white paper measuring 9'43⁄4" × 9' 5" (287 × 288 cm). The piece is in the Tate Modern collection in London.[1]

Description and background

[edit]It consists of a number of colored shapes arranged in a spiral pattern, as suggested by the title. Matisse first drew the snail, then used the colored paper to interpret it. The composition pairs complementary colors: Matisse gave the work the alternative title La Composition Chromatique.[1] From the early-to-mid-1940s Matisse was in increasingly poor health, and was suffering from arthritis. Eventually by 1950 he stopped painting in favor of gouaches découpées, paper cutouts.[2] The Snail is a major example of this final body of works.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Henri Matisse, The Snail 1953, Tate Gallery, retrieved August 5, 2012]

- ^ "Henri Matisse" Archived 2008-08-04 at the Wayback Machine, Pompidou Centre. Retrieved 25 December 2007.