Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

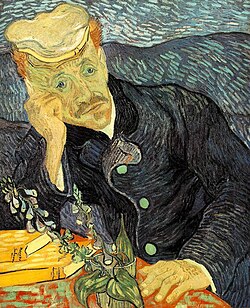

Oil painting

View on Wikipedia

Oil painting is a painting method involving the procedure of painting with pigments combined with a drying oil as the binder. It has been the most common technique for artistic painting on canvas, wood panel, or copper for several centuries. The advantages of oil for painting images include "greater flexibility, richer and denser color, the use of layers, and a wider range from light to dark".[1]

The oldest known oil paintings were created by Buddhist artists in Afghanistan, and date back to the 7th century AD.[2] Oil paint was later developed by Europeans for painting statues and woodwork from at least the 12th century, but its common use for painted images began with Early Netherlandish painting in Northern Europe, and by the height of the Renaissance, oil painting techniques had almost completely replaced the use of egg tempera paints for panel paintings in most of Europe, though not for Orthodox icons or wall paintings, where tempera and fresco, respectively, remained the usual choice.

Commonly used drying oils include linseed oil, poppy seed oil, walnut oil, and safflower oil. The choice of oil imparts a range of properties to the paint, such as the amount of yellowing or drying time. The paint could be thinned with turpentine. Certain differences, depending on the oil, are also visible in the sheen of the paints. An artist might use several different oils in the same painting depending on specific pigments and effects desired. The paints themselves also develop a particular consistency depending on the medium. The oil may be boiled with a resin, such as pine resin or frankincense, to create a varnish to provide protection and texture. The paint itself can be molded into different textures depending on its plasticity.

Techniques

[edit]

Traditional oil painting techniques often begin with the artist sketching the subject onto the canvas with charcoal or thinned paint. Oil paint is usually mixed with linseed oil, artist grade mineral spirits, or other solvents to make the paint thinner, faster or slower drying. (Because the solvents thin the oil in the paint, they can also be used to clean paint brushes.) A basic rule of oil paint application is 'fat over lean', meaning that each additional layer of paint should contain more oil than the layer below to allow proper drying. If each additional layer contains less oil, the final painting will crack and peel. The consistency on the canvas depends on the layering of the oil paint. This rule does not ensure permanence; it is the quality and type of oil that leads to a strong and stable paint film.

Other media can be used with the oil, including cold wax, resins, and varnishes. These additional media can aid the painter in adjusting the translucency of the paint, the sheen of the paint, the density or 'body' of the paint, and the ability of the paint to hold or conceal the brushstroke. These aspects of the paint are closely related to the expressive capacity of oil paint.

Traditionally, paint was most often transferred to the painting surface using paintbrushes, but there are other methods, including using palette knives and rags. Palette knives can scrape off any paint from a canvas and can also be used for application. Oil paint remains wet longer than many other types of artists' materials, enabling the artist to change the color, texture, or form of the figure. At times, the painter might even remove an entire layer of paint and begin anew. This can be done with a rag and some turpentine for a time while the paint is wet, but after a while the hardened layer must be scraped off. Oil paint dries by oxidation, not evaporation, and is usually dry to the touch within two weeks (some colors dry within days).

History

[edit]

The earliest known surviving oil paintings are Buddhist murals created c. 650 AD in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Bamiyan is a historic settlement along the Silk Road and is famous for the Bamiyan Buddhas, a series of giant statues, behind which rooms and tunnels are carved from the rock. The murals are located in these rooms. The artworks display a wide range of pigments and ingredients and even include the use of a final varnish layer. The application technique and refined level of the paint media used in the murals and their survival into the present day suggest that oil paints had been used in Asia for some time before the 7th century. The technique used, of binding pigments in oil, was unknown in Europe for another 900 years or so.[3][4][5]

In a treatise written about 1125, monk Theophilus Presbyter (a pseudonymous author who is sometimes identified as Roger of Helmarshausen[6]) gives instructions for oil-based painting in his treatise, De diversis artibus ('on various arts'), written about 1125.[7] At this period, it was probably used for painting sculptures, carvings, and wood fittings, perhaps especially for outdoor use. Surfaces exposed to the weather or of items like shields—both those used in tournaments and those hung as decorations—were more durable when painted in oil-based media than when painted in traditional tempera paints. Cennino Cennini, in his Book of Art, also mentions and describes the oil technique. Most European Renaissance sources, in particular Vasari, falsely credit northern European painters of the 15th century, and Jan van Eyck in particular, with the invention of oil paints.[8]

However, early Netherlandish paintings with artists like Van Eyck and Robert Campin in the early and mid-15th century were the first to make oil the usual painting medium and explore the use of layers and glazes, followed by the rest of Northern Europe, and then Italy.

Such works were painted on wooden panels, but towards the end of the 15th century canvas began to be used as a support, as it was cheaper, easier to transport, allowed larger works, and did not require complicated preliminary layers of gesso (a fine type of plaster). Venice, where sail-canvas was easily available, was a leader in the move to canvas. Small cabinet paintings were also made on metal, especially copper plates. These supports were more expensive but very firm, allowing intricately fine detail. Often printing plates from printmaking were reused for this purpose. The increasing use of oil spread through Italy from Northern Europe, starting in Venice in the late 15th century. By 1540, the previous method for painting on panel (tempera) had become all but extinct, although Italians continued to use chalk-based fresco for wall paintings, which was less successful and durable in damper northern climates.

Renaissance techniques used several thin almost transparent layers or glazes, usually each allowed to dry before the next was added, greatly increasing the time a painting took. The underpainting or ground beneath these was usually white (typically gesso coated with a primer), allowing light to reflect through the layers. But van Eyck, and Robert Campin a little later, used a wet-on-wet technique in places, painting a second layer soon after the first. Initially, the aim was, as with the established techniques of tempera and fresco, to produce a smooth surface when no attention was drawn to the brushstrokes or texture of the painted surface. Among the earliest impasto effects, using a raised or rough texture in the surface of the paint, are those from the later works of the Venetian painter Giovanni Bellini, around 1500.[9]

This became much more common in the 16th century, as many painters began to draw attention to the process of their painting, by leaving individual brushstrokes obvious, and a rough painted surface. Another Venetian, Titian, was a leader in this. In the 17th century some artists, including Rembrandt, began to use dark grounds. Until the mid-19th century, there was a division between artists who exploited "effects of handling" in their paintwork, and those who continued to aim at "an even, glassy surface from which all evidences of manipulation had been banished".[10]

Before the 19th century, artists or their apprentices ground pigments and mixed their paints for the range of painting media. This made portability difficult and kept most painting activities confined to the studio. This changed when tubes of oil paint became widely available following the American portrait painter John Goffe Rand's invention of the squeezable or collapsible metal tube in 1841. Artists could mix colors quickly and easily, which enabled, for the first time, relatively convenient plein air painting (a common approach in French Impressionism)

Ingredients

[edit]

The linseed oil itself comes from the flax seed, a common fiber crop. Linen, a "support" for oil painting (see relevant section), also comes from the flax plant. Safflower oil or the walnut or poppyseed oil or Castor Oil are sometimes used in formulating lighter colors like white because they "yellow" less on drying than linseed oil, but they have the slight drawback of drying more slowly and may not provide the strongest paint film. Linseed oil tends to dry yellow and can change the hue of the color. In some regions, this technique is referred to as the drying oil technique.

Recent advances in chemistry have produced modern water miscible oil paints that can be used and cleaned up with water. Small alterations in the molecular structure of the oil create this water miscible property.

Supports for oil painting

[edit]

The earliest oil paintings were almost all panel paintings on wood, which had been seasoned and prepared in a complicated and rather expensive process with the panel constructed from several pieces of wood, although such support tends to warp. Panels continued to be used well into the 17th century, including by Rubens, who painted several large works on wood. The artists of the Italian regions moved towards canvas in the early 16th century, led partly by a wish to paint larger images, which would have been too heavy as panels. Canvas for sails was made in Venice and so easily available and cheaper than wood.

Smaller paintings, with very fine detail, were easier to paint on a very firm surface, and wood panels or copper plates, often reused from printmaking, were often chosen for small cabinet paintings even in the 19th century. Portrait miniatures normally used very firm supports, including ivory, or stiff paper card.

Traditional artists' canvas is made from linen, but less expensive cotton fabric has been used. The artist first prepares a wooden frame called a "stretcher" or "strainer". The difference between the two names is that stretchers are slightly adjustable, while strainers are rigid and lack adjustable corner notches. The canvas is then pulled across the wooden frame and tacked or stapled tightly to the back edge. Then the artist applies a "size" to isolate the canvas from the acidic qualities of the paint. Traditionally, the canvas was coated with a layer of animal glue (modern painters use rabbit skin glue) as the size and primed with lead white paint, sometimes with added chalk. Panels were prepared with a gesso, a mixture of glue and chalk.

Modern acrylic "gesso" is made of titanium dioxide with an acrylic binder. It is frequently used on canvas, whereas real gesso is not suitable for canvas. The artist might apply several layers of gesso, sanding each smooth after it has dried. Acrylic gesso is very difficult to sand. One manufacturer makes a "sandable" acrylic gesso, but it is intended for panels only and not canvas. It is possible to make the gesso a particular color, but most store-bought gesso is white. The gesso layer, depending on its thickness, will tend to draw the oil paint into the porous surface. Excessive or uneven gesso layers are sometimes visible on the surface of finished paintings as a change that's not from the paint.

Standard sizes for oil paintings were set in France in the 19th century. The standards were used by most artists, not only the French, as it was—and still is—supported by the main suppliers of artists' materials. Size 0 (toile de 0) to size 120 (toile de 120) is divided into separate "runs" for figures (figure), landscapes (paysage), and marines (marine) that more or less preserve the diagonal. Thus a 0 figure corresponds in height with a paysage 1 and a marine 2.[11]

Although surfaces like linoleum, wooden panel, paper, slate, pressed wood, Masonite, and cardboard have been used, the most popular surface since the 16th century has been canvas, although many artists used panel through the 17th century and beyond. The panel is more expensive, heavier, harder to transport, and prone to warp or split in poor conditions. For fine detail, however, the absolute solidity of a wooden panel has an advantage.

Some artists are now painting directly onto prepared Aluminium Composite Material (ACM) panels. Others combine the perceived benefits of canvas and panel by gluing canvas onto panels made from ACM, Masonite or other material.

Process

[edit]

Oil paint is made by mixing pigments of colors with an oil medium. Since the 19th century the different main colors are purchased in paint tubes pre-prepared before painting begins, further shades of color are usually obtained by mixing small quantities as the painting process is underway. An artist's palette, traditionally a thin wood board held in the hand, is used for holding and mixing paints. Pigments may be any number of natural or synthetic substances with color, such as sulfides for yellow or cobalt salts for blue. Traditional pigments were based on minerals or plants, but many have proven unstable over long periods. Modern pigments often use synthetic chemicals. The pigment is mixed with oil, usually linseed, but other oils may be used. The various oils dry differently, which creates assorted effects.

A brush is most commonly employed by the artist to apply the paint, often over a sketched outline of their subject (which could be in another medium). Brushes are made from a variety of fibers to create different effects. For example, brushes made with hog bristles might be used for bolder strokes and impasto textures. Fitch hair and mongoose hair brushes are fine and smooth, and thus answer well for portraits and detail work. Even more expensive are red sable brushes (weasel hair). The finest quality brushes are called "kolinsky sable"; these brush fibers are taken from the tail of the Siberian weasel. This hair keeps a superfine point, has smooth handling, and good memory (it returns to its original point when lifted off the canvas), known to artists as a brush's "snap". Floppy fibers with no snap, such as squirrel hair, are generally not used by oil painters.

In the past few decades, many synthetic brushes have been marketed. These are very durable and can be quite good, as well as cost efficient.

Brushes come in multiple sizes and are used for different purposes. The type of brush also makes a difference. For example, a "round" is a pointed brush used for detail work. "Flat" brushes are used to apply broad swaths of color. "Bright" is a flat brush with shorter brush hairs, used for "scrubbing in". "Filbert" is a flat brush with rounded corners. "Egbert" is a very long, and rare, filbert brush. The artist might also apply paint with a palette knife, which is a flat metal blade. A palette knife may also be used to remove paint from the canvas when necessary. A variety of unconventional tools, such as rags, sponges, and cotton swabs, may be used to apply or remove paint. Some artists even paint with their fingers.

Old masters usually applied paint in thin layers known as "glazes" that allow light to penetrate completely through the layer, a method also simply called "indirect painting". This technique is what gives oil paintings their luminous characteristics. This method was first perfected through an adaptation of the egg tempera painting technique (egg yolks used as a binder, mixed with pigment), and was applied by the Early Netherlandish painters in Northern Europe with pigments usually ground in linseed oil. This approach has been called the "mixed technique" or "mixed method" in modern times. The first coat (the underpainting) is laid down, often painted with egg tempera or turpentine-thinned paint. This layer helps to "tone" the canvas and to cover the white of the gesso. Many artists use this layer to sketch out the composition. This first layer can be adjusted before proceeding further, an advantage over the "cartooning" method used in fresco technique. After this layer dries, the artist might then proceed by painting a "mosaic" of color swatches, working from darkest to lightest. The borders of the colors are blended when the "mosaic" is completed and then left to dry before applying details.

Artists in later periods, such as the Impressionist era (late 19th century), often expanded on this wet-on-wet method, blending the wet paint on the canvas without following the Renaissance-era approach of layering and glazing. This method is also called "alla prima". This method was created due to the advent of painting outdoors, instead of inside a studio, because while outside, an artist did not have the time to let each layer of paint dry before adding a new layer. Several contemporary artists use a combination of both techniques to add bold color (wet-on-wet) and obtain the depth of layers through glazing.

When the image is finished and has dried for up to a year, an artist often seals the work with a layer of varnish that is typically made from dammar gum crystals dissolved in turpentine. Such varnishes can be removed without disturbing the oil painting itself, to enable cleaning and conservation. Some contemporary artists decide not to varnish their work, preferring the surface unvarnished to avoid a glossy look.

Examples of famous works

[edit]-

Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck, 1434 (on panel)

-

La donna velata, Raphael, 1516

-

The Rape of Europa, Titian, 1562

-

The Raising of the Cross, Peter Paul Rubens, 1610–11

-

The Milkmaid, Johannes Vermeer, 1658–1660

-

The Toilet of Venus, François Boucher, 1751

-

The Blue Boy, Thomas Gainsborough, 1770

-

Charge in the Somosierra Gorge, Piotr Michałowski, 1837

-

The Card Players, Paul Cézanne, 1892

-

Le Grand Canal, Venice, Henri Le Sidaner, 1906

-

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Pablo Picasso, 1907

-

The Kiss (Der Kuß), Gustav Klimt, 1907/8

-

Composition VII, Wassily Kandinsky, 1913

-

Motive from Tartu, Villem Ormisson, 1937

-

Nighthawks, Edward Hopper, 1942

Citations

[edit]- ^ Osborne (1970), p. 787

- ^ "World's oldest use of oil paint found in Afghanistan". World Archaeology. 6 July 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Synchrotron light unveils oil in ancient Buddhist paintings from Bamiyan". European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. 21 April 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Afghan caves hold world's first oil paintings: expert". ABC News. 25 January 2008.

- ^ "Earliest Oil Paintings Discovered". Live Science. 22 April 2008.

- ^ "Theophilus: German writer and painter". Encyclopedia Britannica. 11 April 2024 [First published 20 July 1998].

- ^ Osborne (1970), pp. 787, 1132

- ^ Borchert (2008), pp. 92–94

- ^ Osborne (1970), p. 787

- ^ Osborne (1970), pp. 787–788

- ^ Haaf, Beatrix (1987). "Industriell vorgrundierte Malleinen. Beiträge zur Entwicklungs-, Handels- und Materialgeschichte". Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung. 1: 7–71.

General and cited references

[edit]- Borchert, Till-Holger (2008). Van Eyck. London: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-5687-8.

- Osborne, Harold, ed. (1970). The Oxford Companion to Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019866107X.

Further reading

[edit]- Chieffo, Clifford T. (1976). Contemporary Oil Painter's Handbook. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-131-70167-0.

- Mayer, Ralph (1940). The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques. Comprehensive reference book.

External links

[edit] Introduction to Art at Wikibooks

Introduction to Art at Wikibooks Media related to Oil paintings at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oil paintings at Wikimedia Commons