Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tokyo Express

View on Wikipedia| Tokyo Express | |

|---|---|

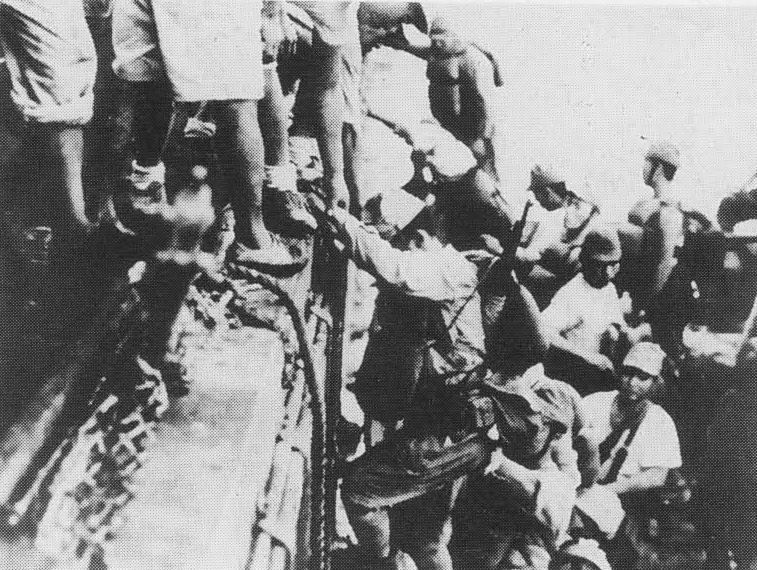

Japanese troops load onto a warship in preparation for a "Tokyo Express" run sometime in 1942. | |

| Active | August 1942 – November 1943 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Imperial Japanese Armed Forces |

| Branch | Imperial Japanese Navy |

| Type | Ad hoc military logistics organization |

| Role | Supply and reinforcement to Japanese Army and Navy units located in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea |

| Size | Varied |

| Garrison/HQ | Rabaul, New Britain Shortland Islands and Buin, Solomon Islands |

| Nicknames | Cactus Express "Rat" or "Ant" transportation (Japanese names) |

| Engagements | Battle of Cape Esperance Battle of Tassafaronga Operation Ke Battle of Blackett Strait Battle of Kula Gulf Battle of Kolombangara Battle of Vella Gulf Battle off Horaniu Naval Battle of Vella Lavella Battle of Cape St. George |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Gunichi Mikawa Raizo Tanaka Shintarō Hashimoto[1] Matsuji Ijuin |

The Tokyo Express was the name given by Allied forces to the use of Imperial Japanese Navy ships at night to deliver personnel, supplies, and equipment to Japanese forces operating in and around New Guinea and the Solomon Islands during the Pacific campaign of World War II. The operation involved loading personnel or supplies aboard fast warships (mainly destroyers), later submarines, and using the warships' speed to deliver the personnel or supplies to the desired location and return to the originating base all within one night so Allied aircraft could not intercept them by day.

Name

[edit]

The original name of the resupply missions was "The Cactus Express", coined by Allied forces on Guadalcanal, who used the code name "Cactus" for the island. After the U.S. press began referring to it as the "Tokyo Express", apparently in order to preserve operational security for the code word, Allied forces also began to use the phrase. The Japanese themselves called the night resupply missions "Rat Transportation" (鼠輸送, nezumi yusō), because they took place at night.

History

[edit]

Night transportation was necessary for Japanese forces due to Allied air superiority in the South Pacific, established soon after the Allied landings on Guadalcanal and the subsequent establishment of Henderson Field as a base for the "Cactus Air Force" in August 1942. Delivery of troops and material by slow transport ships to Japanese forces on Guadalcanal and New Guinea soon proved too vulnerable to daytime air attack. The Japanese Combined Fleet commander Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto therefore authorized the use of faster warships to make the deliveries at night when the threat of detection was much less and aerial attack minimal.[2]

The Tokyo Express began soon after the Battle of Savo Island in August 1942 and continued until late in the Solomon Islands campaign when one of the last large Express runs was intercepted and almost completely destroyed in the Battle of Cape St. George on November 26, 1943. Because the destroyers typically used were not configured for cargo handling, many supplies were sealed inside steel drums lashed together and simply pushed into the water without the ships stopping; ideally, the drums would float ashore or were picked up by barge. However, many drums were lost or damaged; a typical night in December 1942 resulted in 1500 drums being rolled into the sea, with only 300 recovered.[3]

Most of the warships used for Tokyo Express missions came from the Eighth Fleet, based at Rabaul and Bougainville, although ships from Combined Fleet units based at Truk were often temporarily attached for use in Express missions. The warship formations assigned to Express missions were often formally designated as the "Reinforcement Unit", but the size and composition of this unit varied from mission to mission.[4]

John F. Kennedy

[edit]John F. Kennedy's PT-109 was lost on a "poorly planned and uncoordinated" attack on a Tokyo Express run on the night of 1-2 August 1943.[5] Fifteen PT boats with sixty torpedoes fired over thirty and did not register a single hit, while PT-109 was rammed and sunk by the destroyer Amagiri, which was returning from her supply run, estimated to be traveling in excess of 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) with no running lights.

Strategic importance

[edit]The Tokyo Express ended up being a lose-lose gambit for the Japanese, because many destroyers were lost during the fifteen months of the Tokyo Express, for no gain. These ships could not be replaced by the stressed Japanese shipyards, and were already in short supply. In addition, they were desperately needed for convoy duty to protect Japanese shipping supplying the Home Islands from the depredations of American submarines.[6]

The Imperial Japanese Navy was caught in a Catch-22, since American airpower from Henderson Field denied the Japanese the use of slow cargo ships. Compared to destroyers, cargo ships were much more economical in fuel usage while having the capacity to carry full loads of troops plus sufficient equipment and supplies, and having efficient cargo loading and unloading equipment. However, they were slow and comparatively un-maneuverable, and thus easily sunk – not merely sending irreplaceable supplies and freighters to the bottom but leaving their increasingly desperate troops un-provisioned and ever less able to fight.

As a result, the Navy was in essence forced to "fight as uneconomical a campaign as could possibly be imagined", since in using destroyers they had to "expend much larger quantities of fuel than they wanted" considering Imperial Japan's disadvantage in oil supply, and this "fuel was used to place very valuable (and vulnerable) fleet destroyers in an exposed forward position while delivering an insufficient quantity of men and supplies to the American meatgrinder on the island".[7] Even at its best (with only one-fifth of the supplies dropped ever making it to shore) the destroyer strategy amounted to waging a losing war of attrition on land and an extremely expensive rolling naval defeat.

Thereafter, the Japanese increasingly relied on convoys of barges escorted by armored boats to replenish or evacuate their forces. A typical configuration allowing for the transport of 1,000 men, 300 miles, would consist of 2 Soukoutei-class armored boats as escort for 2 special large landing barges (Toku Daihatsu), 40 large landing barges (Daihatsu), and 15 small landing barges (Shohatsu).[8]

Demise

[edit]By early February of 1943 the Allies had triumphed on Guadalcanal and had effective control of the area of The Slot that had been used to man and provision it, preventing a highly stressed Japanese military from being able to wage an effort to retake it and its extremely valuable Henderson Airfield. To signify final victory over the Japanese on the island, General Alexander Patch, commander of the Allied land forces on the island, messaged his superior, Admiral William F. Halsey on February 9, 1943, "Tokyo Express no longer has terminus on Guadalcanal."[9]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- References

- ^ Evans 176

- ^ Coombe, Derailing the Tokyo Express, p. 33.

- ^ "HyperWar: History of USMC Operations in WWII, Vol. I: Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, Part VI [Chapter 9]". www.ibiblio.org. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ Frank, p. 559.

- ^ National Geographic Search for the PT-109 DVD

- ^ Parillo

- ^ "Oil and Japanese Strategy in the Solomons: A Postulate". www.combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ "Japanese Use of Military Barges, from Tactical and Technical Trends, No. 43". lonesentry.com. January 27, 1944. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ "The Guadalcanal Campaign (David Llewellyn James)". Angelfire. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- Bibliography

- Brown, David (1990). Warship Losses of World War Two. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-914-X.

- Coombe, Jack D. (1991). Derailing the Tokyo Express. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 0-8117-3030-1.

- Crenshaw, Russell Sydnor (1998). South Pacific Destroyer: The Battle for the Solomons from Savo Island to Vella Gulf. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-136-X.

- D'Albas, Andrieu (1965). Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Devin-Adair Pub. ISBN 0-8159-5302-X.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941-1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-097-1.

- Evans, David C. (1986). "The Struggle for Guadalcanal". The Japanese Navy in World War II: In the Words of Former Japanese Naval Officers (2nd ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-316-4.

- Frank, Richard (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-58875-4.

- Griffith, Brig. Gen. Samuel B (USMC) (1974). "Part 96: Battle For the Solomons". History of the Second World War. Hicksville, NY, USA: BPC Publishing.

- Parillo, Mark (2006). "Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II". In Higham, Robin; Harris, Stephen (eds.). Why Air Forces Fail: the Anatomy of Defeat. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2374-5.

- Hara, Tameichi (1961). Japanese Destroyer Captain. New York & Toronto: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-27894-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Kilpatrick, C. W. (1987). Naval Night Battles of the Solomons. Exposition Press. ISBN 0-682-40333-4.

- Lord, Walter (2006) [1977]. Lonely Vigil; Coastwatchers of the Solomons. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-466-3.

- Lundstrom, John B. (2005). The First Team And the Guadalcanal Campaign: Naval Fighter Combat from August to November 1942 (New ed.). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-472-8.

- McGee, William L. (2002). The Solomons Campaigns, 1942-1943: From Guadalcanal to Bougainville--Pacific War Turning Point, Volume 2 (Amphibious Operations in the South Pacific in WWII). BMC Publications. ISBN 0-9701678-7-3.

- Miller, Thomas G. (1969). Cactus Air Force. Admiral Nimitz Foundation. ISBN 0-934841-17-9.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943, vol. 5 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-58305-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) Online views of selections of the book:[1] - Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, vol. 6 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Castle Books. ISBN 0-7858-1307-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Potter, E. B. (2005). Admiral Arleigh Burke. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-692-5.

- Roscoe, Theodore (1953). United States Destroyer Operations in World War Two. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-726-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Duncan Anderson (ed.). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942-43. Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

External links

[edit]- Hough, Frank O.; Ludwig, Verle E.; Shaw, Henry I. Jr. "Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- Parshall, Jon; Bob Hackett; Sander Kingsepp; Allyn Nevitt. "Imperial Japanese Navy Page (Combinedfleet.com)". Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- Shaw, Henry I. (1992). "First Offensive: The Marine Campaign For Guadalcanal". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Shaw, Henry I.; Douglas T. Kane (1963). "Volume II: Isolation of Rabaul". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- Reports of General MacArthur: Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II - Part I. United States Army Center of Military History, www.history.army.mil. 1994. Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2006-12-08.- Translation of the official record by the Japanese Demobilization Bureaux detailing the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy's participation in the Southwest Pacific area of the Pacific War.

- Zimmerman, John L. (1949). "The Guadalcanal Campaign". Marines in World War II Historical Monograph. Retrieved 2006-07-04.