Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

City manager

View on Wikipedia| Part of the Politics series |

| Common forms of local government |

|---|

|

|

A city manager is an official appointed as the administrative manager of a city in the council–manager form of city government.[1] Local officials serving in this position are referred to as the chief executive officer (CEO) or chief administrative officer (CAO) in some municipalities.[2][3]

Responsibilities

[edit]In a technical sense, the term "city manager", in contrast to "chief administrative officer" (CAO), implies more discretion and independent authority that is set forth in a charter or some other body of codified law, as opposed to duties being assigned on a varying basis by a single superior, such as a mayor.[4]

As the top appointed official in the city, the city manager is typically responsible for most if not all of the day-to-day administrative operations of the municipality, in addition to other expectations.[5][6]

Some of the basic roles, responsibilities, and powers of a city manager include:

- Supervision of day-to-day operations of all city departments and staff through department heads;

- Oversight of all recruitment, dismissal, disciplining and suspensions;

- Preparation, monitoring, and execution of the city budget, which includes submitting each year to the council a proposed budget package with options and recommendations for its consideration and possible approval;

- Main technical advisor to the council on overall governmental operations;

- Public relations, such as meeting with citizens, citizen groups, businesses, and other stakeholders (the presence of a mayor may alter this function somewhat);

- Operating the city with a professional understanding of how all city functions operate together to their best effect;

- Attends all council meetings, but does not have any voting rights[7]

- Additional duties that may be assigned by the council[5][6]

The responsibilities may vary depending upon charter provisions and other local or state laws, rules, and regulations. In addition, many states, such as the states of New Hampshire and Missouri, have codified in law the minimum functions a local "manager" must perform.[8] The City Manager position focuses on efficiency and providing a certain level of service for the lowest possible cost.[9] The competence of a city manager can be assessed using composite indicators.[10]

Manager members of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) are bound by a rather rigid and strongly enforced code of ethics that was originally established in 1924. Since that time the code had been up-dated/revised on seven occasions, the latest taking place in 1998. The updates have taken into account the evolving duties, responsibilities, and expectations of the profession; however the core dictate of the body of the code--"to integrity; public service; seek no favor; exemplary conduct in both personal and professional matters; respect the role and contributions of elected officials; exercise the independence to do what is right; political neutrality; serve the public equitably and governing body members equally; keep the community informed about local government matters; and support and lead our employ-ees"—have not changed since the first edition.[11]

History

[edit]

Most sources trace the first city manager to Staunton, Virginia[12] in 1908. Some of the other cities that were among the first to employ a manager were Sumter, South Carolina (1912) and Dayton, Ohio (1914); Dayton was featured in the national media, and became a national standard. The first "City Manager's Association" meeting of eight city managers was in December 1914.[13] The city manager, operating under the council-manager government form, was created in part to remove city government from the power of the political parties, and place management of the city into the hands of an outside expert who was usually a business manager or engineer, with the expectation that the city manager would remain neutral to city politics. By 1930, two hundred American cities used a city manager form of government.[14]

In 1913, the city of Dayton, Ohio suffered a great flood, and responded with the innovation of a paid, non-political city manager, hired by the commissioners to run the bureaucracy; civil engineers were especially preferred. Other small or middle-sized American cities, especially in the west, adopted the idea.

In Europe, smaller cities in the Netherlands were specially attracted by the plan.[15]

By 1940, there were small American cities with city managers that would grow enormously by the end of the century: Austin, Texas; Charlotte, North Carolina; Dallas, Texas; Dayton, Ohio; Rochester, New York; and San Diego, California.[16]

Profile

[edit]In the early years of the profession, most managers came from the ranks of the engineering professions.[17] Today, the typical and preferred background and education for the beginning municipal manager is a master's degree in Public Administration (MPA), and at least several years' experience as a department head in local government, or as an assistant city manager. As of 2005, more than 60% of those in the profession had a MPA, MBA, or other related higher-level degree.[18]

The average tenure of a manager is now 7–8 years, and has risen gradually over the years. Tenures tend to be less in smaller communities and higher in larger ones, and they tend to vary as well, depending on the region of the country.[18][19]

Educational Level of Local Government Managers (MYB = Municipal Yearbook; SOP = State of the Profession survey):[7]

| 1935 | 1964 | 1974 | 1984 | 1995 | 2000 | 2006 | 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High school or less | 42% | 14% | 6% | 2% | 4% | 2% | 4% | 1% |

| Some college, no degree | 21% | 22% | 18% | 10% | — | 9% | 11% | 6% |

| Bachelor's degree | 35% | 41% | 38% | 30% | 24% | 26% | 27% | 23% |

| MPA degree | — | 18% | — | — | 44% | — | 37% | 43% |

| Other graduate degree | 2% | 5% | 38% | 58% | 28% | 63% | 21% | 27% |

| Source | 1940 MYB | 1965 MYB | 1990 MYB | 1996 MYB | 2001 MYB | 2006 SOP survey | 2012 SOP Survey | |

| Sample size | n = 449 | n = 1,582 | n not reported | n =2 65 | n = 3,175 | n = 2,752 | n = 1,816 | |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ City of Naperville

- ^ "City Manager's Office | Union City, CA". www.unioncity.org. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ "Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) | icma.org". icma.org. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ Svara, James H. and Kimberly L. Nelson. (2008, August). Taking Stock of the Council-Manager Form at 100. Public Management Magazine, pp 6-14, at: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-08-31. Retrieved 2009-12-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Council Manager Form of Government, ICMA publication" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ^ a b Sample Ordinance, ICMA.

- ^ a b Nelson, Kimberly L.; Svara, James H. (2015-01-01). "The Roles of Local Government Managers in Theory and Practice: A Centennial Perspective". Public Administration Review. 75 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1111/puar.12296. ISSN 1540-6210.

- ^ MRS Archived 2013-07-28 at the Wayback Machine NH RSA

- ^ MacDonald, Lynn. "The Impact Of Government Structure On Local Public Expenditures." Public Choice 136.3/4 (2008): 457-473. Political Science Complete. Web. 25 Sept. 2015.

- ^ Marozzi, Marco; Bolzan, Mario (2015). "Skills and training requirements of municipal directors: A statistical assessment". Quality and Quantity. 50 (3): 1093–1115. doi:10.1007/s11135-015-0192-2. S2CID 121952677.

- ^ "ICMA Code of Ethics page". Archived from the original on 2007-11-06. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ James, Herman G. (1914). "The City Manager Plan, the Latest in American City Government". American Political Science Review. 8 (4). Cambridge University Press: 602–613. doi:10.2307/1945258. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1945258. S2CID 145433051.

- ^ "City managing, a new profession". The Independent. Dec 14, 1914. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ Robert Bruce Fairbanks; Patricia Mooney-Melvin; Zane L. Miller (2001). Making Sense of the City: Local Government, Civic Culture, and Community Life in Urban America. Ohio State University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780814208816.

- ^ Stefan Couperus, "The managerial revolution in local government: municipal management and the city manager in the USA and the Netherlands 1900–1940." Management & Organizational History (2014) 9#4 pp: 336-352.

- ^ Harold A. Stone et al., City Manager Government in Nine Cities (1940); Frederick C. Mosher et al., City Manager Government in Seven Cities (1940)

- ^ Stillman, Richard J. (1974). The Rise of the City Manager: A Public Professional in Local Government. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ a b ICMA statistics[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ammons, David M and Matthew J. Bosse. (2005). "Tenure of City Managers: Examining the Dual Meanings of 'Average Tenure'." State & Local Government Review, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 61-71. at: [1]

Further reading

[edit]- Kemp, Roger L. Managing America's Cities: A Handbook for Local Government Productivity, McFarland and Co., Jefferson, NC, USA, and London, Eng., UK 1998(ISBN 0-7864-0408-6).

- _______, Model Government Charters: A City, County, Regional, State, and Federal Handbook, McFarland and Co., Jefferson, NC, USA, and London, Eng., UK, 2003 (ISBN 978-0-7864-3154-0)

- _______, Forms of Local Government: A Handbook on City, County and Regional Options, McFarland and Co., Jefferson, NC, USA, and London, Eng., UK, 2007 (ISBN 978-0-7864-3100-7).

- Stillman, Richard Joseph. The rise of the city manager: A public professional in local government. (University of New Mexico Press, 1974)

- Weinstein, James. "Organized business and the city commission and manager movements." Journal of Southern History (1962): 166–182. in JSTOR

- White, Leonard D. The city manager (1927)

- Woodruff, Clinton Rogers (1928). "The City-Manager Plan". American Journal of Sociology. 33 (4): 599–613.

External links

[edit]- International City/County Management Association, ICMA is the professional and educational organization for chief appointed managers, administrators, and assistants in cities, towns, counties, and regional entities throughout the world.

- Staunton, Virginia: Birthplace Of City Manager Form Of Government, a history on the city manager system of government.

City manager

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Origins in the Progressive Era

The council-manager form of government, featuring a professionally trained city manager appointed by an elected council to handle administrative duties, emerged during the Progressive Era (roughly 1890s–1920s) as a response to widespread municipal corruption, inefficiency, and political machine dominance in American cities. Rapid urbanization and industrialization had strained traditional mayor-council systems, where patronage, ward-based politics, and unqualified elected officials often prioritized cronyism over public service, leading to scandals like those in New York and Chicago. Progressives, drawing from business efficiency models, advocated separating policymaking from day-to-day operations to introduce expert management akin to corporate practices, thereby reducing partisan interference and enhancing accountability.[7][8][9] Precursors to the full council-manager system included the Galveston Plan of 1901, where Texas's Galveston adopted a commission government after a devastating hurricane exposed administrative failures; this model centralized power in a small elected commission with appointed experts, influencing later reforms by emphasizing at-large elections and professional administration over ward bosses. The idea crystallized further through advocacy by reform groups like the National Municipal League, which promoted nonpartisan, streamlined governance to combat "bossism." By 1908, Staunton, Virginia, implemented an early version by hiring a general manager under its council, though without formal charter changes, marking an experimental step toward professionalization.[10][11] The first formal charter adoption occurred in Sumter, South Carolina, in 1912, incorporating core principles of a small elected council appointing a manager responsible for operations. This gained national prominence when Dayton, Ohio—a city of about 116,000 residents—adopted the plan in 1913 following its own flood crisis, hiring engineer Henry M. Waite as its inaugural city manager in 1914; Dayton's success in rapid infrastructure improvements and cost savings demonstrated the model's viability, spurring over 500 municipalities to follow suit by 1930. The International City Managers' Association, formed in 1914, institutionalized the movement, standardizing qualifications and ethics for managers trained often in engineering or public administration.[5][12][10]Expansion and Institutionalization

Following the pioneering adoption in Staunton, Virginia, in 1908 and formalization in Sumter, South Carolina, in 1912, the council-manager form expanded rapidly after Dayton, Ohio, implemented it in 1914 as the first sizable city, drawing widespread national interest.[5] By 1918, 100 local governments had adopted the plan.[5] The number of council-manager communities grew to 400 by 1930, reflecting broader appeal amid Progressive Era demands for efficient, nonpartisan administration.[5] Post-World War II expansion accelerated, with an average of 50 annual adoptions from 1945 to 1985, culminating in 2,563 U.S. local governments operating under the form by December 1985.[5] Peak yearly gains included 159 new adoptions in 1973 and 133 in 1976.[5] By the early 21st century, the form had become dominant, governing over half of U.S. cities with populations exceeding 5,000—53 percent as of 2008—and serving more than 92 million residents.[13] As of recent counts, 3,003 ICMA-recognized U.S. local governments use the council-manager structure, underscoring its enduring prevalence in medium- and large-sized municipalities.[5] Institutionalization advanced through the City Managers' Association, founded in 1914 with 32 initial members to promote professional standards and knowledge sharing among managers.[5] In 1924, the group adopted its first code of ethics, emphasizing apolitical administration and accountability, and renamed itself the International City Managers’ Association to reflect cross-border adoptions.[5] Subsequent evolutions, including the 1969 shift to International City Management Association and 1991 expansion to International City/County Management Association, formalized training, credentialing, and recognition of general management practices, embedding the profession within structured norms.[5] These efforts, sustained by ongoing ICMA initiatives in ethics, leadership development, and policy guidance, solidified the city manager's role as a career-oriented, expertise-driven position insulated from partisan politics.[5]Government Structure

Council-Manager System Mechanics

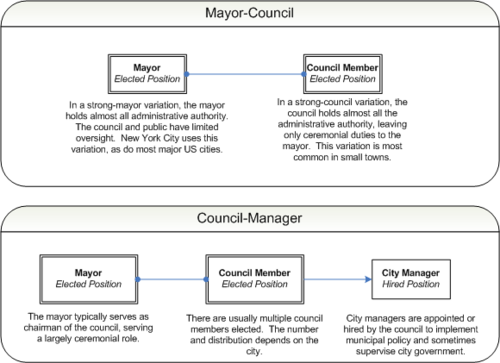

In the council-manager system, an elected council serves as the legislative and policymaking body, responsible for enacting ordinances, approving budgets, and setting the strategic direction for the municipality.[3] The council appoints a professional city manager to act as the chief executive officer, who is tasked with implementing council policies without direct involvement in legislative decisions.[14] This structure emphasizes a clear division between policy formulation by elected officials and administrative execution by appointed experts, aiming to insulate daily operations from partisan politics.[3] The city manager oversees all administrative functions, including directing department heads, managing personnel, preparing the annual budget for council review, and ensuring efficient service delivery.[15] Unlike elected executives, the manager is selected based on qualifications in public administration, often holding advanced degrees or certifications from bodies like the International City/County Management Association (ICMA), and serves at the council's discretion, removable by majority vote without cause.[3] This at-will employment fosters accountability to the council while allowing the manager to make impartial operational decisions, such as hiring, firing, and resource allocation, free from electoral pressures.[14] Council-manager interactions occur primarily through regular meetings where the manager provides reports, policy recommendations, and budget proposals, but the council refrains from directing specific administrative actions to maintain the separation of roles.[16] The council retains oversight by approving major contracts, land use decisions, and fiscal plans, while the manager executes these directives and advises on feasibility based on operational data.[15] In cases of policy disputes, the council's authority prevails, as the manager's role is advisory and implementational, not vetoing or initiating legislation independently.[17] This system's mechanics promote professional management by centralizing executive power in a non-partisan appointee, with empirical adoption in over 3,500 U.S. municipalities as of recent surveys, reflecting its prevalence in cities seeking administrative efficiency over strong executive personalities.[3] Variations exist, such as ceremonial mayors selected from the council, but the core principle remains the council's collective policy control and the manager's operational autonomy under that framework.[14]Comparison to Mayor-Council Form

The council-manager system, featuring an appointed city manager as chief executive, contrasts with the mayor-council system, where an elected mayor holds executive authority. In the council-manager form, the elected council retains legislative and policy-making powers, while the manager implements policies and manages daily operations, including hiring and firing staff.[18] In mayor-council governments, the council legislates, but the mayor exercises executive control, often with veto powers and direct appointment authority over department heads.[19] Key structural differences influence governance dynamics:| Characteristic | Council-Manager | Mayor-Council |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Selection | Appointed by council | Elected by voters |

| Executive Tenure | At-will, indefinite | Fixed term (typically 4 years) |

| Policy Role | Council sets policy; manager executes | Mayor proposes and executes; council legislates |

| Administrative Control | Manager hires/fires staff professionally | Mayor appoints, often politically |

| Accountability | Indirect via council | Direct to voters |

Core Responsibilities

Operational and Administrative Duties

The city manager serves as the chief administrative officer responsible for directing the day-to-day operations of municipal departments, ensuring efficient execution of services such as public works, police and fire protection, planning, economic development, parks and recreation, sanitation, utilities, and resource recovery.[1] This includes supervising department heads to maintain ethical, transparent, and effective service delivery, often through performance measurement systems that track outcomes in areas like road maintenance, recycling programs, and emergency response.[1] [25] In personnel management, the city manager appoints, supervises, disciplines, and removes administrative officers and employees, except where limited by law or charter provisions, delegating authority to department heads for subordinate roles.[26] This encompasses recruiting and hiring staff across functions like public safety and public works to foster organizational excellence and align workforce efforts with community objectives.[1] [25] Administrative duties involve enforcing municipal laws, ordinances, and council policies; preparing meeting agendas and reports on operations; and keeping the council informed of administrative activities and emerging needs.[1] [26] The manager directs all departments subject to oversight, conducts routine correspondence, and handles fiscal year-end summaries of administrative performance to promote accountability without encroaching on legislative policy-making.[26]Financial and Policy Implementation

The city manager holds primary responsibility for formulating and executing the municipal budget, a process that begins with compiling revenue forecasts from sources such as taxes, fees, and grants, alongside detailed expenditure projections for city operations. This budget proposal is presented to the city council for review and approval, typically annually, ensuring alignment with policy priorities while maintaining fiscal discipline.[27] Once enacted, the manager directs its implementation across departments, authorizing expenditures, tracking variances through regular financial reporting, and adjusting allocations as needed to prevent deficits or overspending.[28] Compliance with legal standards, including debt limits and auditing requirements under frameworks like the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), falls under the manager's oversight to safeguard public funds.[29] In policy implementation, the city manager serves as the executive arm of the council, operationalizing adopted ordinances and strategic plans by assigning tasks to department heads, procuring resources, and coordinating interdepartmental efforts. For instance, if the council enacts a policy for infrastructure upgrades, the manager develops timelines, vendor contracts, and performance metrics to execute it efficiently, often drawing on professional expertise to refine vague directives into actionable programs.[30] This role emphasizes apolitical administration, where the manager advises on feasibility based on data-driven assessments rather than electoral pressures, though execution remains accountable to council oversight. Empirical analyses of council-manager systems indicate enhanced fiscal outcomes, such as reduced per capita spending on administrative functions compared to mayor-council forms, attributed to professional management practices that prioritize cost controls and revenue optimization.[22][31]Professional Profile

Qualifications and Selection Process

City managers typically possess advanced educational credentials and substantial professional experience in public administration. A bachelor's degree in fields such as public administration, political science, or business administration serves as a foundational requirement for many positions, while a master's degree—often in public administration (MPA), public policy, or business administration—is held by approximately two-thirds of surveyed city managers.[25] The International City/County Management Association (ICMA), the primary professional body for local government managers, recommends a master's degree with a concentration in public administration as a minimum guideline for effective performance in the role.[26] Preferred qualifications frequently include the ICMA Credentialed Manager (ICMA-CM) designation, which requires demonstrated expertise through peer-reviewed experience and continuous professional development.[32] Beyond formal education, city managers must exhibit extensive practical experience, usually several years in progressively responsible roles within local government, encompassing areas like budgeting, personnel management, and policy implementation. Successful candidates demonstrate leadership skills, ethical integrity, and a commitment to enhancing community quality of life, as emphasized by ICMA standards.[33] Variations exist by jurisdiction and city size; smaller municipalities may accept equivalent combinations of education and experience in lieu of advanced degrees, whereas larger cities prioritize proven track records in economic development and intergovernmental relations.[29] The selection process for a city manager is initiated and controlled by the elected city council, which appoints the individual by majority vote without a fixed term, allowing for removal at the council's discretion.[34] Councils often engage executive search firms affiliated with ICMA or specialized recruiters to conduct nationwide or regional searches, defining desired qualities such as administrative expertise and strategic vision through a detailed profile.[35] Applications undergo initial screening for alignment with these criteria, followed by structured interviews, reference checks, and sometimes assessment centers involving simulated exercises to evaluate decision-making under pressure.[36] To attract high-caliber candidates, the process generally excludes direct public involvement, focusing instead on confidentiality to mitigate political influences that could deter applicants seeking apolitical roles.[35] Finalists negotiate employment contracts covering salary—often ranging from $150,000 to over $300,000 annually depending on city size—performance incentives, and severance provisions, with council approval required for appointment. Background investigations, including financial and criminal checks, are standard to ensure suitability.[37] This merit-based approach aligns with the council-manager system's emphasis on professional expertise over electoral politics, though council dynamics can influence outcomes if ideological alignments are prioritized over qualifications.[38]Challenges and Tenure Dynamics

City managers frequently encounter political conflicts with city councils, which arise from disagreements over policy implementation, administrative style, or resource allocation, often serving as a primary driver of turnover.[39][40] Such tensions stem from the inherent friction between the manager's nonpartisan, professional expertise and the elected officials' responsiveness to constituent pressures, exacerbating instability in environments with frequent council turnover or ideological divides.[41] Additional challenges include managing crises that threaten organizational credibility, such as public scandals or service disruptions, requiring managers to communicate effectively while preserving operational continuity.[42] Human resource dilemmas, including unresolved employee disputes or staffing shortages, further strain decision-making, demanding impartial resolutions amid limited authority over elected bodies.[43] Tenure dynamics reflect these pressures, with average lengths varying by municipal stability and manager competence. Empirical data indicate that city managers in the United States typically serve 5 to 7 years per position, though medians have trended upward from approximately 3.5 years in the 1960s to around 7 years by the early 2000s in surveyed council-manager cities.[44][41] For managers completing terms between 1980 and 2002, the mean tenure was 6.9 years, influenced by factors like prior government experience and budgeting proficiency, which correlate with extended service.[45][46] Shorter tenures often result from "push" factors, including council distrust or electoral shifts, while "pull" factors like promotional opportunities encourage voluntary departures.[40] Longer tenures are associated with stable political environments and effective relationship-building with councils, mitigating burnout and cynicism that plague frequent movers.[47][48] In contrast, high-turnover municipalities exhibit patterns of rapid succession, where incoming managers inherit unresolved conflicts, perpetuating cycles of instability; for instance, policy-style clashes account for a significant portion of forced exits over mere administrative disputes.[39][49] These dynamics underscore the vulnerability of appointed roles to electoral volatility, with professional longevity hinging on navigating adaptive challenges like evolving community demands without partisan entanglement.[9]Empirical Evidence on Performance

Efficiency and Service Delivery Outcomes

Empirical research comparing council-manager and mayor-council forms of government reveals mixed evidence regarding efficiency gains, with no consistent demonstration of systematic cost advantages for council-manager systems. Studies examining fiscal performance, such as those analyzing per capita expenditures and resource allocation, often find no significant differences in cost minimization between the two structures. For instance, Deno and Mehay (1987) reported no substantial variations in productive efficiency, attributing outcomes more to local economic factors than governmental form. Similarly, Hayes and Chang (1990) observed comparable resource use efficiencies, suggesting that professional management alone does not yield measurable budgetary savings absent other reforms.[31][50] On service delivery, findings are similarly inconclusive, though some evidence points to modestly higher operational outputs in council-manager cities for specific functions. Folz and Abdelrazek (2009) analyzed solid waste management and found council-manager municipalities achieving higher collection frequencies and recycling rates, potentially linked to centralized administrative expertise. However, broader surveys of resident perceptions, such as those by Wood and Fan (2008), indicate no uniform superiority, with service satisfaction varying by city size and demographics rather than form. A comprehensive review by Carr (2015) synthesizes these results, concluding weak support for propositions that council-manager governments deliver higher-quality services or overall effectiveness, as self-reported advantages in innovation and reduced internal conflict do not reliably translate to tangible outcomes like faster response times or lower error rates.[50][21]| Key Study | Finding on Efficiency/Service Delivery | Government Forms Compared |

|---|---|---|

| Deno & Mehay (1987) | No systematic efficiency differences in costs or outputs | Council-manager vs. mayor-council |

| Folz & Abdelrazek (2009) | Higher service levels (e.g., waste management) in council-manager | Council-manager vs. mayor-council |

| Carr (2015) review | Mixed/weak evidence for superior service quality or fiscal efficiency | Council-manager vs. mayor-council |