Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

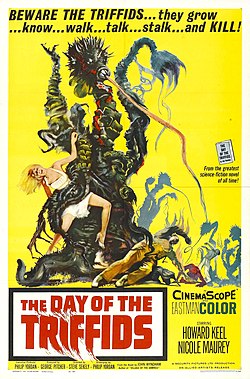

Triffid

View on Wikipedia| Triffid | |

|---|---|

A triffid drawn by its creator, John Wyndham | |

| First appearance | The Day of the Triffids (1951 novel) |

| Last appearance | The Day of the Triffids (2009 TV series) |

| Created by | John Wyndham |

| In-universe information | |

| Type | Carnivorous plant |

The triffid is a fictional tall, mobile, carnivorous plant species, created by John Wyndham in his 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids, which has since been adapted for film and television. The word "triffid" has become a common reference in British English to describe large, invasive or menacing-looking plants.[1]

Fictional history

[edit]Origins

[edit]In the novel, the origin of the triffid species is explained as being the creation of the Soviet Union (portrayed as being a mysterious country), although the exact way they came to be present around the world is unknown. The main character, Bill Masen speculates as follows:

It is my guess that over the Pacific Ocean ... cannon-shells from Russian fighters ... blew to pieces a certain twelve-inch cube of plywood ... in which, according to Ferdor, the seeds were packed. [...] Millions of gossamer-strung triffid seeds, free to drift wherever the winds of the world should take them ...[2]

The 1962 film adaptation portrays them as extraterrestrial lifeforms transported to Earth by comets, contradicting the novel.

In the 1981 TV series, the triffids were the creation of real-life Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko. The seeds were spread across the globe when a plane smuggling them out of Russia was shot down during the Cold War.

In the 2009 two-part TV series, the triffids are a naturally occurring species from Zaire, discovered by the West and selectively bred as an alternative to fossil fuels, to avert global warming.

Name

[edit]Triffid refers to the plant's three "legs".[3] In the novel a dozen names beginning with tri-, with a long i vowel (as in PRICE), had been bandied about before the term standardized on "triffid", with a short i (as in KIT).[3]

Initial appearance and cultivation

[edit]In the novel, it is stated that the first triffids appeared in equatorial regions. Though they develop faster in tropical zones, triffids soon established themselves worldwide, outside the polar and desert regions. When it was discovered that triffids are venomous, they were almost exterminated, until they were identified as the source of valuable oil. Farms were then built to cultivate them.

Upon the discovery that docking their stingers renders them harmless, docked triffids became fashionable in public and private gardens. These triffids are safe provided they are pruned annually, as they take two years to fully regrow their stingers. Farmed triffids are not docked because undocked triffids produce higher quality oil.

Characteristics

[edit]In the novel

[edit]

The plant can be divided into three components: base, trunk, and head (which contains a venomous sting). Adult triffids are typically 7 feet (2.1 m) in height. European triffids never exceed 8 feet (2.4 m); however, in tropical climates, they can reach 10 feet (3.0 m).

The base of a triffid is a large muscle-like root mass, comprising three blunt appendages. When dormant, these appendages draw nutrients, as on a normal plant. When active, triffids use these appendages to propel themselves. The character Masen describes the triffid's locomotion thus:

When it "walked" it moved rather like a man on crutches. Two of the blunt "legs" slid forward, then the whole thing lurched as the rear one drew almost level with them, then the two in front slid forward again. At each "step" the long stem whipped violently back and forth; it gave one a kind of seasick feeling to watch it. As a method of progress it looked both strenuous and clumsy—faintly reminiscent of young elephants at play. One felt that if it were to go on lurching for long in that fashion it would be bound to strip all its leaves if it did not actually break its stem. Nevertheless, ungainly though it looked, it was contriving to cover the ground at something like an average walking pace.[2]

Above the base are upturned leafless sticks which the triffid drums against its stem. The exact purpose of this is not explained; it is originally assumed that they are part of the reproductive system, but Bill Masen's colleague Walter Lucknor believes they are used for communication. Removal of the sticks causes the triffid to physically deteriorate.

The upper part of a triffid consists of a stem ending in a funnel-like formation containing a sticky substance which traps insects, much like a pitcher plant. Also housed within the funnel is a stinger which, when fully extended, can measure 10 feet (3.0 m) in length. When attacking, a triffid will lash the sting at its target, primarily aiming for its prey's face or head, with considerable speed and force. Contact with bare skin can kill a person instantly. Once its prey has been stung and killed, a triffid will root itself beside the body and feeds on it as it decomposes.

Triffids reproduce by inflating a dark green pod below the top of the funnel until it bursts, releasing white seeds (95% of which are infertile) into the air.[2]

It is not clear whether the triffids are intelligent or acting on instinct. The character Lucknor states that although triffids lack a central nervous system, they display what he considers intelligence:

And there's certainly intelligence there, of a kind. Have you noticed that when they attack they always go for the unprotected parts? Almost always the head—but sometimes the hands. And another thing: if you look at the statistics of casualties, just take notice of the proportion that has been stung across the eyes and blinded. It's remarkable—and significant.[2]

The triffids also show awareness by their habit of herding blind people into cramped spaces to kill more easily[4] and rooting themselves beside houses, waiting for the occupants.[5]

In other adaptations and sequels

[edit]The triffids portrayed on screen and in sequels often differ in appearance from Wyndham's original concept.

In Steve Sekely's 1962 film adaptation, the triffids (now given the binomial name Triffidus celestus) were designed with flaying tentacles below their stems, which they use as slashing weapons and to drag their dead prey. Also, their stinger is shown as a gas-propelled projectile, rather than a coiled tendril. Finally, the film triffids are vulnerable to sea water.

The 2009 TV adaptation shows the triffids dragging themselves with prehensile roots which can also constrict their prey. Their stalk is surrounded by large agave-like leaves and they secrete their oil (green rather than the novel's pink) from their surfaces. Their stingers, which in previous film adaptations could not penetrate glass, are powerful enough to shatter windows, like those of the original triffids of the novel. Instead of a cup they have a pink flower-like head, resembling a cross between a lily and a sweet pea, that enlarges before releasing the sting.

In the Simon Clark sequel novel The Night of the Triffids, a small number of North American triffids reach 60 feet (18 m) in height.[6] Aquatic triffids also appear but remain largely unseen, with the exceptions of their stingers: the latter described as prehensile.[7] One character in the novel, Gabriel Deeds, speculates that the vibrations made by the triffids' sticks serve as a form of echolocation.[8]

Other mentions of the triffids

[edit]Triffids, based on the 1981 TV design, and a triffid gun, make an appearance in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier, a 2007 graphic novel written by Alan Moore and drawn by Kevin O'Neill.

In the online videogame Kingdom of Loathing, triffids are monsters located within an area known as "the Spooky Forest".[9]

In the mobile game for "The Simpsons" named The Simpsons: Tapped Out, one of the options to plant in Cletus' Farm are triffids, which comically bring about the 'end of humanity'.

Reference is made to the original film in "Science Fiction/Double Feature", the opening song of The Rocky Horror Show. "And I really got hot when I saw Janette Scott/Fight a triffid that spits poison and kills".

In the computer and mobile rogue-like video game Cataclysm: Dark Days Ahead, Triffids are a faction composed of human-sized plant creatures that are aggressive to the player.[10] The more dangerous version of these creatures is the "Triffid Queen", described as being cow-sized and very competent fighters with high hit points.[11] If the player is able to defeat a "Triffid Heart", the creatures will not continue to spawn in that area of the map.[12]

Other uses of the name

[edit]Chromolaena odorata, a serious invasive weed, is sometimes known as "triffid weed".[13][14][15][16]

The Triffids were an alternative rock band from 1978-89, originating in Perth, Western Australia.[17]

Specialised time-lapse camera rigs used to film plant movements in the 2022 television series The Green Planet were nicknamed "Triffids" after the fictional plants.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ "Triffid definition and meaning". Collins Dictionary.

- ^ a b c d Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids, ch. 2.

- ^ a b John Wyndham, The Day Of The Triffids, chapter 2

- ^ Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids, ch.5.

- ^ Wyndham, The Day of the Triffids, ch. 11.

- ^ Clark, The Night of the Triffids, ch. 41.

- ^ Clark, The Night of the Triffids, ch. 31.

- ^ Clark, The Night of the Triffids, ch. 26.

- ^ "Triffid". Kol.coldfront.net. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Triffid - The Cataclysm: Dark Days Ahead Wiki". Cddawiki.chezzo.com. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Triffid queen - The Cataclysm: Dark Days Ahead Wiki". Cddawiki.chezzo.com. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Triffid heart (Creature) - the Cataclysm: Dark Days Ahead Wiki". Cddawiki.chezzo.com. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Triffid weed Chromolaena odorata (Asteraceae)". Invasives South Africa. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ "Chromolaena odorata (草本) 香澤蘭". Taiwan Invasive Species Database. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ Lalith Gunasekera, Invasive Plants: A guide to the identification of the most invasive plants of Sri Lanka, Colombo 2009, p. 116–117.

- ^ "Siam Weed, Chromolaena, Eupatorium, Bitter Bush, Christmas Bush, Devil Weed, Hagonoy, Jack in the Bush, Triffid Weed, Turpentine Weed, Armstrong's Weed, King Weed, Paraffin Weed, Paraffin Bush, Baby Tea, Agonoi, Siam-kraut. Chromolaena odorata (L.) R.M.King & H.Rob". Weeds Australia. Centre for Invasive Species Solutions (CISS). Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ "The Triffids - Save what you can". Thetriffids.com. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "BBC One - The Green Planet - The technology that captured The Green Planet". BBC. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

External links

[edit]- The BBC's Triffid Home page

- Triffid Alley - Hampstead at the Wayback Machine (archived November 3, 2016)