Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

CRISPR

View on Wikipedia

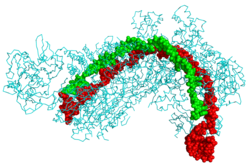

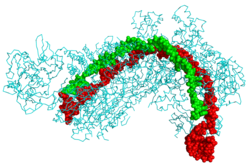

| Cascade (CRISPR-associated complex for antiviral defense) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

CRISPR Cascade protein (cyan) bound to CRISPR RNA (green) and phage DNA (red)[1] | |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | CRISPR | ||||||

| Entrez | 947229 | ||||||

| PDB | 4QYZ | ||||||

| RefSeq (Prot) | NP_417241.1 | ||||||

| UniProt | P38036 | ||||||

| |||||||

CRISPR (/ˈkrɪspər/; acronym of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea.[3] Each sequence within an individual prokaryotic CRISPR is derived from a DNA fragment of a bacteriophage that had previously infected the prokaryote or one of its ancestors.[4][5] These sequences are used to detect and destroy DNA from similar bacteriophages during subsequent infections. Hence these sequences play a key role in the antiviral (i.e. anti-phage) defense system of prokaryotes and provide a form of heritable,[4] acquired immunity.[3][6][7][8] CRISPR is found in approximately 50% of sequenced bacterial genomes and nearly 90% of sequenced archaea.[4]

Cas9 (or "CRISPR-associated protein 9") is an enzyme that uses CRISPR sequences as a guide to recognize and open up specific strands of DNA that are complementary to the CRISPR sequence. Cas9 enzymes together with CRISPR sequences form the basis of a technology known as CRISPR-Cas9 that can be used to edit genes within living organisms.[9][10] This editing process has a wide variety of applications including basic biological research, development of biotechnological products, and treatment of diseases.[11][12] The development of the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technique was recognized by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 awarded to Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna.[13][14]

History

[edit]The CRISPR/Cas system evolved in nature as a means for bacteria to protect themselves from invading viruses and bacteriophages by inserting pieces of their DNA into the host genome. This allowed the adaptive immune system to respond accordingly on a subsequent infection. It was discovered in Streptococcus pyogenes and later found across many other species.

Repeated sequences

[edit]The discovery of clustered DNA repeats took place independently in three parts of the world. The first description of what would later be called CRISPR is fIshino, et al. in 1987. They accidentally cloned part of a CRISPR sequence together with the iap gene (isozyme conversion of alkaline phosphatase) from Escherichia coli.[15][16] The organization of the repeats surpsied them, as clustered repeated sequences are more typically arranged consecutively, without interspersing sequences.[12][16]

In 1993, van Solingen et al., published two articles about a cluster of interrupted direct repeats (DR) in that bacterium. The team recognized the diversity of the sequences that intervened in the direct repeats among different strains of M. tuberculosis[17] and used this property to design a typing method called spoligotyping, which remains in use.[18][19]

Mojica studied the function of repeats in the archaeal genera Haloferax and Haloarcula. Mojica's supervisor surmised that the clustered repeats had a role in segregating replicated DNA into daughter cells during cell division, because plasmids and chromosomes with identical repeat arrays could not coexist in Haloferax volcanii. They noted the transcription of the interrupted repeats for the first time; CRISPR's first full characterization.[19][20] By 2000, Mojica and his students, after an automated search of published genomes, identified interrupted repeats in 20 species of microbes as belonging to the same family.[21] Because those sequences were interspaced, Mojica initially called these sequences "short regularly spaced repeats" (SRSR).[22] In 2001, Mojica and Jansen, who were searching for additional interrupted repeats, proposed the acronym CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) to encompass the numerous acronyms then in use.[20][23] In 2002, Tang, et al. showed evidence that CRISPR repeat regions in Archaeoglobus fulgidus were transcribed into long RNA molecules subsequently processed into unit-length small RNAs, plus some longer forms of 2, 3, or more spacer-repeat units.[24][25]

In 2005, Barrangou discovered that S thermophilus, after iterative phage infection challenges, develops increased phage resistance due to the incorporation of additional CRISPR spacer sequences.[26][27]

CRISPR-associated systems

[edit]A major advance came with Jansen's observation that the prokaryote repeat cluster was accompanied by four homologous genes, CRISPR-associated systems, Cas 1–4. The Cas proteins showed helicase and nuclease motifs, suggesting a role in the dynamic structure of the CRISPR loci.[28] However, CRISPR's function remained enigmatic.

In 2005, three independent research groups showed that some CRISPR spacers are derived from phage DNA and extrachromosomal DNA such as plasmids.[32][33][34] In effect, the spacers are fragments of DNA gathered from viruses that previously attacked the cell. The source of the spacers was a sign that the CRISPR-cas system could have a role in adaptive immunity in bacteria.[29][35] All three studies proposing this idea were initially rejected by high-profile journals, but eventually appeared elsewhere.[36]

The first publication[33] proposing a role of CRISPR-Cas in microbial immunity, by Mojica, et al., predicted a role for the RNA transcript of spacers on target recognition in a mechanism that could be analogous to the RNA interference system used by eukaryotic cells. Koonin and colleagues extended this RNA interference hypothesis by proposing mechanisms of action for the different CRISPR-Cas subtypes according to the predicted function of their proteins.[37]

Experimental work by several groups revealed the basic mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas immunity. In 2007, the first experimental evidence that CRISPR was part of the adaptive immune system was published.[7][12] A CRISPR region in Streptococcus thermophilus acquired spacers from the DNA of an infecting bacteriophage. The researchers manipulated the resistance of S. thermophilus to different types of phages by adding and deleting spacers whose sequence matched those found in the phages.[38][39] In 2008, Brouns and Van der Oost identified a complex of Cas proteins called Cascade, that in E. coli cut the CRISPR RNA precursor within the repeats into mature spacer-containing RNA molecules called CRISPR RNA (crRNA), which remained bound to the protein complex.[40] Cascade, crRNA and a helicase/nuclease (Cas3) were required to provide a bacterial host with immunity against infection by a DNA virus. By designing an anti-virus CRISPR, they demonstrated that two orientations of the crRNA (sense/antisense) provided immunity, indicating that the crRNA guides were targeting dsDNA. That year Marraffini and Sontheimer confirmed that a CRISPR sequence of S. epidermidis targeted DNA and not RNA to prevent conjugation. This finding was at odds with the proposed RNA-interference-like mechanism of CRISPR-Cas immunity, although a CRISPR-Cas system that targets foreign RNA was later found in Pyrococcus furiosus.[12][39] A 2010 study reported that CRISPR-Cas cuts strands of both phage and plasmid DNA in S. thermophilus.[41]

In 2012, Jinek et al., fused crRNA and tracrRNA into a single-guide RNA, simplifying Cas9 targeting.[42] Šikšnys, et al., reported that Cas9 from S. thermophilus can target specific DNA by altering crRNA.[43] In 2013, Cong, et al., as well as Mali, et al., applied CRISPR-Cas9 to edit human cell cultures.[44][45] In 2015, Liang, et al., edited human tripronuclear zygotes, achieving successful cleavage in 28 of 54 embryos.[46]

Cas9

[edit]

A simpler CRISPR system from S pyogenes uses Cas9, an endonuclease functioning with two small RNAs—crRNA and tracrRNA—to form a four-component complex.[47][48] In 2012, Doudna and Charpentier simplified this into a two-component system by fusing the RNAs into a single-guide RNA, enabling Cas9 to target and cut specific DNA sequences—a breakthrough that earned them the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[49] Parallel work showed the S. thermophilus Cas9 could be similarly reprogrammed by altering the crRNA sequence.[19] These developments spurred genome editing efforts, including demonstrations by groups led by Zhang and Church showing genome editing in human cells using CRISPR-Cas9.[12][50][51]

Cas12a

[edit]Cas12a, a Class II Type V CRISPR-associated nuclease, was characterized in 2015 and was formerly known as Cpf1.[5] This nuclease is found in the CRISPR-Cpf1 system of bacteria such as Francisella novicida.[6][2] The initial designation, derived from a TIGRFAMs protein family definition established in 2012, reflected the prevalence of this CRISPR-Cas subtype in the Prevotella and Francisella lineages. Cas12a exhibits several key distinctions from Cas9: it generates staggered cuts in double-stranded DNA, in contrast to the blunt ends produced by Cas9;[11] it relies on a 'T-rich' protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (typically 5'-TTTV-3', where V is A, C, or G), offering alternative targeting sites compared to the 'G-rich' PAMs (typically 5'-NGG-3') favored by Cas9;[13] and it requires only a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) for effective targeting, whereas Cas9 necessitates both a crRNA and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA).[5]

Cas13a

[edit]In 2016, the nuclease (formerly known as C2c2) from the bacterium Leptotrichia shahii was characterized by researchers in Zhang's group. Cas13 is an RNA-guided RNA endonuclease, which means that it cleaves single-stranded RNA, but not DNA. Cas13 is guided by its crRNA to a ssRNA target and binds and cleaves the target. Similar to Cas12a, Cas13 remains bound to the target and then cleaves other ssRNA molecules non-discriminately.[52] This collateral cleavage property is exploited in the development of various diagnostic technologies.[53][54][55]

Locus structure

[edit]Repeats and spacers

[edit]The CRISPR array is made up of an AT-rich leader sequence followed by short repeats that are separated by unique spacers.[56] CRISPR repeats typically range in size from 28 to 37 base pairs (bps), though there can be as few as 23 bp and as many as 55 bp.[57] Some show dyad symmetry, implying the formation of a secondary structure such as a stem-loop ('hairpin') in the RNA, while others are designed to be unstructured. The size of spacers in different CRISPR arrays is typically 32 to 38 bp (range 21 to 72 bp).[57] New spacers can appear rapidly as part of the immune response to phage infection.[58] There are usually fewer than 50 units of the repeat-spacer sequence in a CRISPR array.[57]

CRISPR RNA structures

[edit]Cas genes and CRISPR subtypes

[edit]Small clusters of cas genes are often located next to CRISPR repeat-spacer arrays. Collectively the 93 cas genes are grouped into 35 families based on sequence similarity of the encoded proteins. 11 of the 35 families form the cas core, which includes the protein families Cas1 through Cas9. A complete CRISPR-Cas locus has at least one gene belonging to the cas core.[59]

CRISPR-Cas systems fall into two classes. Class 1 systems use a complex of multiple Cas proteins to degrade foreign nucleic acids. Class 2 systems use a single large Cas protein for the same purpose. Class 1 is divided into types I, III, and IV; class 2 is divided into types II, V, and VI.[60] The 6 system types are divided into 33 subtypes.[61] Each type and most subtypes are characterized by a "signature gene" found almost exclusively in the category. Classification is also based on the complement of cas genes that are present. Most CRISPR-Cas systems have a Cas1 protein. The phylogeny of Cas1 proteins generally agrees with the classification system,[62] but exceptions exist due to module shuffling.[59] Many organisms contain multiple CRISPR-Cas systems suggesting that they are compatible and may share components.[63][64] The sporadic distribution of the CRISPR-Cas subtypes suggests that the CRISPR-Cas system is subject to horizontal gene transfer during microbial evolution.

This table is missing information about UniProt and InterPro cross-reference. (October 2020) |

| Class | Cas type | Cas subtype | Signature protein | Function | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I | — | Cas3 | Single-stranded DNA nuclease (HD domain) and ATP-dependent helicase | [65][66] |

| I-A | Cas8a, Cas5 | Cas8 is a Subunit of the interference module that is important in targeting of invading DNA by recognizing the PAM sequence. Cas5 is required for processing and stability of crRNAs. | [62][67] | ||

| I-B | Cas8b | ||||

| I-C | Cas8c | ||||

| I-D | Cas10d | contains a domain homologous to the palm domain of nucleic acid polymerases and nucleotide cyclases | [68][69] | ||

| I-E | Cse1, Cse2 | ||||

| I-F | Csy1, Csy2, Csy3 | Type IF-3 have been implicated in CRISPR-associated transposons | [62] | ||

| I-G[Note 1] | GSU0054 | [70] | |||

| III | — | Cas10 | Homolog of Cas10d and Cse1. Binds CRISPR target RNA and promotes stability of the interference complex | [69][71] | |

| III-A | Csm2 | Not determined | [62] | ||

| III-B | Cmr5 | Not determined | [62] | ||

| III-C | Cas10 or Csx11 | [62][71] | |||

| III-D | Csx10 | [62] | |||

| III-E | [70] | ||||

| III-F | [70] | ||||

| IV | — | Csf1 | [70] | ||

| IV-A | [70] | ||||

| IV-B | [70] | ||||

| IV-C | [70] | ||||

| 2 | II | — | Cas9 | Nucleases RuvC and HNH together produce DSBs, and separately can produce single-strand breaks. Ensures the acquisition of functional spacers during adaptation. | [72][73] |

| II-A | Csn2 | Ring-shaped DNA-binding protein. Involved in primed adaptation in Type II CRISPR system. | [74] | ||

| II-B | Cas4 | Endonuclease that works with cas1 and cas2 to generate spacer sequences | [75] | ||

| II-C | Characterized by the absence of either Csn2 or Cas4 | [76] | |||

| V | — | Cas12 | Nuclease RuvC. Lacks HNH. | [60][77] | |

| V-A | Cas12a (Cpf1) | Auto-processing pre-crRNA activity for multiplex gene regulation | [70][78] | ||

| V-B | Cas12b (C2c1) | [70] | |||

| V-C | Cas12c (C2c3) | [70] | |||

| V-D | Cas12d (CasY) | [70] | |||

| V-E | Cas12e (CasX) | [70] | |||

| V-F | Cas12f (Cas14, C2c10) | [70] | |||

| V-G | Cas12g | [70] | |||

| V-H | Cas12h | [70] | |||

| V-I | Cas12i | [70] | |||

| V-K[Note 2] | Cas12k (C2c5) | Type V-K have been implicated in CRISPR-associated transposons. | [70] | ||

| V-U | C2c4, C2c8, C2c9 | [70] | |||

| VI | — | Cas13 | RNA-guided RNase | [60][79] | |

| VI-A | Cas13a (C2c2) | [70] | |||

| VI-B | Cas13b | [70] | |||

| VI-C | Cas13c | [70] | |||

| VI-D | Cas13d | [70] | |||

| VI-X | Cas13x.1 | RNA dependent RNA polymerase, Prophylactic RNA-virus inhibition | [80] | ||

| VI-Y | [80] |

Mechanism

[edit]

(1) Acquisition begins by recognition of invading DNA by Cas1 and Cas2 and cleavage of a protospacer.

(2) The protospacer is ligated to the direct repeat adjacent to the leader sequence and

(3) single strand extension repairs the CRISPR and duplicates the direct repeat. The crRNA processing and interference stages occur differently in each of the three major CRISPR systems.

(4) The primary CRISPR transcript is cleaved by cas genes to produce crRNAs.

(5) In type I systems Cas6e/Cas6f cleave at the junction of ssRNA and dsRNA formed by hairpin loops in the direct repeat. Type II systems use a trans-activating (tracr) RNA to form dsRNA, which is cleaved by Cas9 and RNaseIII. Type III systems use a Cas6 homolog that does not require hairpin loops in the direct repeat for cleavage.

(6) In type II and type III systems secondary trimming is performed at either the 5' or 3' end to produce mature crRNAs.

(7) Mature crRNAs associate with Cas proteins to form interference complexes.

(8) In type I and type II systems, interactions between the protein and PAM sequence are required for degradation of invading DNA. Type III systems do not require a PAM for successful degradation and in type III-A systems basepairing occurs between the crRNA and mRNA rather than the DNA, targeted by type III-B systems.

CRISPR-Cas immunity is a natural process of bacteria and archaea.[81] CRISPR-Cas prevents bacteriophage infection, conjugation and natural transformation by degrading foreign nucleic acids that enter the cell.[39]

Spacer acquisition

[edit]When a microbe is invaded by a bacteriophage, the first stage of the immune response is to capture phage DNA and insert it into a CRISPR locus in the form of a spacer. Cas1 and Cas2 are found in both types of CRISPR-Cas immune systems, which indicates that they are involved in spacer acquisition. Mutation studies confirmed this hypothesis, showing that removal of Cas1 or Cas2 stopped spacer acquisition, without affecting CRISPR immune response.[82][83][84][85][86]

Multiple Cas1 proteins have been characterised and their structures resolved.[87][88][89] Cas1 proteins have diverse amino acid sequences. However, their crystal structures are similar and all purified Cas1 proteins are metal-dependent nucleases/integrases that bind to DNA in a sequence-independent manner.[63] Representative Cas2 proteins have been characterised and possess either (single strand) ssRNA-[90] or (double strand) dsDNA-[91][92] specific endoribonuclease activity.

In the I-E system of E. coli, Cas1 and Cas2 form a complex where a Cas2 dimer bridges two Cas1 dimers.[93] In this complex, Cas2 performs a non-enzymatic scaffolding role,[93] binding double-stranded fragments of invading DNA, while Cas1 binds the single-stranded flanks of the DNA and catalyses their integration into CRISPR arrays.[94][95][96] New spacers are usually added at the beginning of the CRISPR next to the leader sequence creating a chronological record of viral infections.[97] In E. coli a histone like protein called integration host factor (IHF), which binds to the leader sequence, is responsible for the accuracy of this integration.[98] IHF also enhances integration efficiency in the type I-F system of Pectobacterium atrosepticum,[99] but in other systems, different host factors may be required[100]

Protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM)

[edit]Bioinformatic analysis of regions of phage genomes that were excised as spacers (termed protospacers) revealed that they were not randomly selected but instead were found adjacent to short (3–5 bp) DNA sequences termed protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM). Analysis of CRISPR-Cas systems showed PAMs to be important for type I and type II, but not type III systems during acquisition.[34][101][102][103][104][105] In type I and type II systems, protospacers are excised at positions adjacent to a PAM sequence, with the other end of the spacer cut using a ruler mechanism, thus maintaining the regularity of the spacer size in the CRISPR array.[106][107] The conservation of the PAM sequence differs between CRISPR-Cas systems and appears to be evolutionarily linked to Cas1 and the leader sequence.[105][108]

New spacers are added to a CRISPR array in a directional manner,[32] occurring preferentially,[58][101][102][109][110] but not exclusively, adjacent[104][107] to the leader sequence. Analysis of the type I-E system from E. coli demonstrated that the first direct repeat adjacent to the leader sequence is copied, with the newly acquired spacer inserted between the first and second direct repeats.[85][106]

The PAM sequence appears to be important during spacer insertion in type I-E systems. That sequence contains a strongly conserved final nucleotide (nt) adjacent to the first nt of the protospacer. This nt becomes the final base in the first direct repeat.[86][111][112] This suggests that the spacer acquisition machinery generates single-stranded overhangs in the second-to-last position of the direct repeat and in the PAM during spacer insertion. However, not all CRISPR-Cas systems appear to share this mechanism as PAMs in other organisms do not show the same level of conservation in the final position.[108] It is likely that in those systems, a blunt end is generated at the very end of the direct repeat and the protospacer during acquisition.

Insertion variants

[edit]Analysis of Sulfolobus solfataricus CRISPRs revealed further complexities to the canonical model of spacer insertion, as one of its six CRISPR loci inserted new spacers randomly throughout its CRISPR array, as opposed to inserting closest to the leader sequence.[107]

Multiple CRISPRs contain many spacers to the same phage. The mechanism that causes this phenomenon was discovered in the type I-E system of E. coli. A significant enhancement in spacer acquisition was detected where spacers already target the phage, even mismatches to the protospacer. This 'priming' requires the Cas proteins involved in both acquisition and interference to interact with each other. Newly acquired spacers that result from the priming mechanism are always found on the same strand as the priming spacer.[86][111][112] This observation led to the hypothesis that the acquisition machinery slides along the foreign DNA after priming to find a new protospacer.[112]

Biogenesis

[edit]CRISPR-RNA (crRNA), which later guides the Cas nuclease to the target during the interference step, must be generated from the CRISPR sequence. The crRNA is initially transcribed as part of a single long transcript encompassing much of the CRISPR array.[30] This transcript is then cleaved by Cas proteins to form crRNAs. The mechanism to produce crRNAs differs among CRISPR-Cas systems. In type I-E and type I-F systems, the proteins Cas6e and Cas6f respectively, recognise stem-loops[113][114][115] created by the pairing of identical repeats that flank the crRNA.[116] These Cas proteins cleave the longer transcript at the edge of the paired region, leaving a single crRNA along with a small remnant of the paired repeat region.

Type III systems also use Cas6, however, their repeats do not produce stem-loops. Cleavage instead occurs by the longer transcript wrapping around the Cas6 to allow cleavage just upstream of the repeat sequence.[117][118][119]

Type II systems lack the Cas6 gene and instead utilize RNaseIII for cleavage. Functional type II systems encode an extra small RNA that is complementary to the repeat sequence, known as a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA).[47] Transcription of the tracrRNA and the primary CRISPR transcript results in base pairing and the formation of dsRNA at the repeat sequence, which is subsequently targeted by RNaseIII to produce crRNAs. Unlike the other two systems, the crRNA does not contain the full spacer, which is instead truncated at one end.[72]

CrRNAs associate with Cas proteins to form ribonucleotide complexes that recognize foreign nucleic acids. CrRNAs show no preference between the coding and non-coding strands, which is indicative of an RNA-guided DNA-targeting system.[8][41][82][86][120][121][122] The type I-E complex (commonly referred to as Cascade) requires five Cas proteins bound to a single crRNA.[123][124]

Interference

[edit]During the interference stage in type I systems, the PAM sequence is recognized on the crRNA-complementary strand and is required along with crRNA annealing. In type I systems correct base pairing between the crRNA and the protospacer signals a conformational change in Cascade that recruits Cas3 for DNA degradation.

Type II systems rely on a single multifunctional protein, Cas9, for the interference step.[72] Cas9 requires both the crRNA and the tracrRNA to function and cleave DNA using its dual HNH and RuvC/RNaseH-like endonuclease domains. Basepairing between the PAM and the phage genome is required in type II systems. However, the PAM is recognized on the same strand as the crRNA (the opposite strand to type I systems).

Type III systems, like type I require six or seven Cas proteins binding to crRNAs.[125][126] The type III systems analysed from S. solfataricus and P. furiosus both target the mRNA of phages rather than phage DNA genome,[64][126] which may make these systems uniquely capable of targeting RNA-based phage genomes.[63] Type III systems were also found to target DNA in addition to RNA using a different Cas protein in the complex, Cas10.[127] The DNA cleavage was shown to be transcription dependent.[128]

The mechanism for distinguishing self from foreign DNA during interference is built into the crRNAs and is therefore likely common to all three systems. Throughout the distinctive maturation process of each major type, all crRNAs contain a spacer sequence and some portion of the repeat at one or both ends. It is the partial repeat sequence that prevents the CRISPR-Cas system from targeting the chromosome as base pairing beyond the spacer sequence signals self and prevents DNA cleavage.[129] RNA-guided CRISPR enzymes are classified as type V restriction enzymes.

Evolution

[edit]| CRISPR associated protein Cas2 (adaptation RNase) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crystal structure of a hypothetical protein tt1823 from Thermus thermophilus | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | CRISPR_Cas2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09827 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR019199 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09638 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| CRISPR-associated protein CasA/Cse1 (Type I effector DNase) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | CRISPR_Cse1 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09481 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013381 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09729 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| CRISPR associated protein CasC/Cse3/Cas6 (Type I effector RNase) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crystal structure of a crispr-associated protein from Thermus thermophilus | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | CRISPR_assoc | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08798 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0362 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR010179 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09727 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The cas genes in the adaptor and effector modules of the CRISPR-Cas system are believed to have evolved from two different ancestral modules. A transposon-like element called casposon encoding the Cas1-like integrase and potentially other components of the adaptation module was inserted next to the ancestral effector module, which likely functioned as an independent innate immune system.[130] The highly conserved cas1 and cas2 genes of the adaptor module evolved from the ancestral module while a variety of class 1 effector cas genes evolved from the ancestral effector module.[131] The evolution of these various class 1 effector module cas genes was guided by various mechanisms, such as duplication events.[132] On the other hand, each type of class 2 effector module arose from subsequent independent insertions of mobile genetic elements.[133] These mobile genetic elements took the place of the multiple gene effector modules to create single gene effector modules that produce large proteins which perform all the necessary tasks of the effector module.[133] The spacer regions of CRISPR-Cas systems are taken directly from foreign mobile genetic elements and thus their long-term evolution is hard to trace.[134] The non-random evolution of these spacer regions has been found to be highly dependent on the environment and the particular foreign mobile genetic elements it contains.[135]

CRISPR-Cas can immunize bacteria against certain phages and thus halt transmission. For this reason, Koonin described CRISPR-Cas as a Lamarckian inheritance mechanism.[136] However, this was disputed by a critic who noted, "We should remember [Lamarck] for the good he contributed to science, not for things that resemble his theory only superficially. Indeed, thinking of CRISPR and other phenomena as Lamarckian only obscures the simple and elegant way evolution really works".[137] But as more recent studies have been conducted, it has become apparent that the acquired spacer regions of CRISPR-Cas systems are indeed a form of Lamarckian evolution because they are genetic mutations that are acquired and then passed on.[138] On the other hand, the evolution of the Cas gene machinery that facilitates the system evolves through classic Darwinian evolution.[138]

Coevolution

[edit]Analysis of CRISPR sequences revealed coevolution of host and viral genomes.[139]

The basic model of CRISPR evolution is newly incorporated spacers driving phages to mutate their genomes to avoid the bacterial immune response, creating diversity in both the phage and host populations. To resist a phage infection, the sequence of the CRISPR spacer must correspond perfectly to the sequence of the target phage gene. Phages can continue to infect their hosts' given point mutations in the spacer.[129] Similar stringency is required in PAM or the bacterial strain remains phage sensitive.[102][129]

Rates

[edit]A study of 124 S. thermophilus strains showed that 26% of all spacers were unique and that different CRISPR loci showed different rates of spacer acquisition.[101] Some CRISPR loci evolve more rapidly than others, which allowed the strains' phylogenetic relationships to be determined. A comparative genomic analysis showed that E. coli and S. enterica evolve much more slowly than S. thermophilus. The latter's strains that diverged 250,000 years ago still contained the same spacer complement.[140]

Metagenomic analysis of two acid-mine-drainage biofilms showed that one of the analyzed CRISPRs contained extensive deletions and spacer additions versus the other biofilm, suggesting a higher phage activity/prevalence in one community than the other.[58] In the oral cavity, a temporal study determined that 7–22% of spacers were shared over 17 months within an individual while less than 2% were shared across individuals.[110]

From the same environment, a single strain was tracked using PCR primers specific to its CRISPR system. Broad-level results of spacer presence/absence showed significant diversity. However, this CRISPR added three spacers over 17 months,[110] suggesting that even in an environment with significant CRISPR diversity some loci evolve slowly.

CRISPRs were analysed from the metagenomes produced for the Human Microbiome Project.[141] Although most were body-site specific, some within a body site are widely shared among individuals. One of these loci originated from streptococcal species and contained ≈15,000 spacers, 50% of which were unique. Similar to the targeted studies of the oral cavity, some showed little evolution over time.[141]

CRISPR evolution was studied in chemostats using S. thermophilus to directly examine spacer acquisition rates. In one week, S. thermophilus strains acquired up to three spacers when challenged with a single phage.[142] During the same interval, the phage developed single-nucleotide polymorphisms that became fixed in the population, suggesting that targeting had prevented phage replication absent these mutations.[142]

Another S. thermophilus experiment showed that phages can infect and replicate in hosts that have only one targeting spacer. Yet another showed that sensitive hosts can exist in environments with high-phage titres.[143] The chemostat and observational studies suggest many nuances to CRISPR and phage (co)evolution.

Identification

[edit]CRISPRs are widely distributed among bacteria and archaea[68] and show some sequence similarities.[116] Their most notable characteristic is their repeating spacers and direct repeats. This characteristic makes CRISPRs easily identifiable in long sequences of DNA, since the number of repeats decreases the likelihood of a false positive match.[144]

Analysis of CRISPRs in metagenomic data is more challenging, as CRISPR loci do not typically assemble, due to their repetitive nature or through strain variation, which confuses assembly algorithms. Where many reference genomes are available, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to amplify CRISPR arrays and analyse spacer content.[101][110][145][146][147][148] However, this approach yields information only for specifically targeted CRISPRs and for organisms with sufficient representation in public databases to design reliable polymerase PCR primers. Degenerate repeat-specific primers can be used to amplify CRISPR spacers directly from environmental samples; amplicons containing two or three spacers can be then computationally assembled to reconstruct long CRISPR arrays.[148]

The alternative is to extract and reconstruct CRISPR arrays from shotgun metagenomic data. This is computationally more difficult, particularly with second generation sequencing technologies (e.g. 454, Illumina), as the short read lengths prevent more than two or three repeat units appearing in a single read. CRISPR identification in raw reads has been achieved using purely de novo identification[149] or by using direct repeat sequences in partially assembled CRISPR arrays from contigs (overlapping DNA segments that together represent a consensus region of DNA)[141] and direct repeat sequences from published genomes[150] as a hook for identifying direct repeats in individual reads.

Use by phages

[edit]Another way for bacteria to defend against phage infection is by having chromosomal islands. A subtype of chromosomal islands called phage-inducible chromosomal island (PICI) is excised from a bacterial chromosome upon phage infection and can inhibit phage replication.[151] PICIs are induced, excised, replicated, and finally packaged into small capsids by certain staphylococcal temperate phages. PICIs use several mechanisms to block phage reproduction. In the first mechanism, PICI-encoded Ppi differentially blocks phage maturation by binding or interacting specifically with phage TerS, hence blocking phage TerS/TerL complex formation responsible for phage DNA packaging. In the second mechanism PICI CpmAB redirects the phage capsid morphogenetic protein to make 95% of SaPI-sized capsid and phage DNA can package only 1/3rd of their genome in these small capsids and hence become nonviable phage.[152] The third mechanism involves two proteins, PtiA and PtiB, that target the LtrC, which is responsible for the production of virion and lysis proteins. This interference mechanism is modulated by a modulatory protein, PtiM, binds to one of the interference-mediating proteins, PtiA, and hence achieves the required level of interference.[153]

One study showed that lytic ICP1 phage, which specifically targets Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1, has acquired a CRISPR-Cas system that targets a V. cholera PICI-like element. The system has 2 CRISPR loci and 9 Cas genes. It seems to be homologous to the I-F system found in Yersinia pestis. Moreover, like the bacterial CRISPR-Cas system, ICP1 CRISPR-Cas can acquire new sequences, which allows phage and host to co-evolve.[154][155]

Certain archaeal viruses were shown to carry mini-CRISPR arrays containing one or two spacers. It has been shown that spacers within the virus-borne CRISPR arrays target other viruses and plasmids, suggesting that mini-CRISPR arrays represent a mechanism of heterotypic superinfection exclusion and participate in interviral conflicts.[148]

Applications

[edit]CRISPR gene editing is a revolutionary technology that allows for precise, targeted modifications to the DNA of living organisms. Developed from a natural defense mechanism found in bacteria, CRISPR-Cas9 is the most commonly used system. Gene editing with CRISPR-Cas9 involves a Cas9 nuclease and an engineered guide RNA, which come together to allow for the precise "cutting" of one or both strands of DNA at specific locations within the genome.[156] It makes use of the cell's natural DNA repair systems, including non-homologous end joining, homology-directed repair, or mismatch repair, to modify, insert, or delete genetic material at these specific cut sites.[156][157] This technology has transformed fields such as genetics, medicine,[158][159][160] and agriculture,[161] offering potential treatments for genetic disorders, advancements in crop engineering, and research into the fundamental workings of life. However, its ethical implications and potential unintended consequences have sparked significant debate.[162][163]

See also

[edit]- CRISPR activation

- Anti-CRISPR

- CRISPR/Cas Tools

- CRISPR gene editing

- The CRISPR Journal

- "Designer baby"

- DRACO

- Gene knockout

- Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens

- Glossary of genetics

- Human germline engineering

- Human Nature (2019 documentary film)

- MAGESTIC

- New eugenics

- Prime editing

- RNAi

- SiRNA

- Surveyor nuclease assay

- Synthetic biology

- Zinc finger

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ PDB: 4QYZ: Mulepati S, Héroux A, Bailey S (2014). "Crystal structure of a CRISPR RNA–guided surveillance complex bound to a ssDNA target". Science. 345 (6203): 1479–1484. Bibcode:2014Sci...345.1479M. doi:10.1126/science.1256996. PMC 4427192. PMID 25123481.

- ^ a b Horvath P, Barrangou R (January 2010). "CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea". Science. 327 (5962): 167–170. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..167H. doi:10.1126/science.1179555. PMID 20056882.

- ^ a b Barrangou R (2015). "The roles of CRISPR-Cas systems in adaptive immunity and beyond". Current Opinion in Immunology. 32: 36–41. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2014.12.008. PMID 25574773.

- ^ a b c Hille F, Richter H, Wong SP, Bratovič M, Ressel S, Charpentier E (March 2018). "The Biology of CRISPR-Cas: Backward and Forward". Cell. 172 (6): 1239–1259. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.032. hdl:21.11116/0000-0003-FC0D-4. PMID 29522745.

- ^ a b c Rath D, Amlinger L, Rath A, Lundgren M (October 2015). "The CRISPR-Cas immune system: biology, mechanisms and applications". Biochimie. 117: 119–128. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2015.03.025. PMID 25868999.

- ^ a b Redman M, King A, Watson C, King D (August 2016). "What is CRISPR/Cas9?". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Education and Practice Edition. 101 (4): 213–215. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2016-310459. PMC 4975809. PMID 27059283.

- ^ a b Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H, Richards M, Boyaval P, Moineau S, et al. (March 2007). "CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes". Science. 315 (5819): 1709–1712. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1709B. doi:10.1126/science.1138140. hdl:20.500.11794/38902. PMID 17379808. (registration required)

- ^ a b Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ (December 2008). "CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA". Science. 322 (5909): 1843–1845. Bibcode:2008Sci...322.1843M. doi:10.1126/science.1165771. PMC 2695655. PMID 19095942.

- ^ Bak RO, Gomez-Ospina N, Porteus MH (August 2018). "Gene Editing on Center Stage". Trends in Genetics. 34 (8): 600–611. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2018.05.004. PMID 29908711.

- ^ Zhang F, Wen Y, Guo X (2014). "CRISPR/Cas9 for genome editing: progress, implications and challenges". Human Molecular Genetics. 23 (R1): R40–6. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu125. PMID 24651067.

- ^ a b CRISPR-CAS9, TALENS and ZFNS – the battle in gene editing https://www.ptglab.com/news/blog/crispr-cas9-talens-and-zfns-the-battle-in-gene-editing/ Archived 2021-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Hsu PD, Lander ES, Zhang F (June 2014). "Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering". Cell. 157 (6): 1262–1278. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. PMC 4343198. PMID 24906146.

- ^ a b "Press release: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Wu KJ, Peltier E (7 October 2020). "Nobel Prize in Chemistry Awarded to 2 Scientists for Work on Genome Editing – Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer A. Doudna developed the Crispr tool, which can alter the DNA of animals, plants and microorganisms with high precision". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Rawat A, Roy M, Jyoti A, Kaushik S, Verma K, Srivastava VK (August 2021). "Cysteine proteases: Battling pathogenic parasitic protozoans with omnipresent enzymes". Microbiological Research. 249 126784. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2021.126784. PMID 33989978.

- ^ a b Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A (December 1987). "Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product". Journal of Bacteriology. 169 (12): 5429–5433. doi:10.1128/jb.169.12.5429-5433.1987. PMC 213968. PMID 3316184.

- ^ van Soolingen D, de Haas PE, Hermans PW, Groenen PM, van Embden JD (August 1993). "Comparison of various repetitive DNA elements as genetic markers for strain differentiation and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 31 (8): 1987–1995. doi:10.1128/JCM.31.8.1987-1995.1993. PMC 265684. PMID 7690367.

- ^ Groenen PM, Bunschoten AE, van Soolingen D, van Embden JD (December 1993). "Nature of DNA polymorphism in the direct repeat cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; application for strain differentiation by a novel typing method". Molecular Microbiology. 10 (5): 1057–1065. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00976.x. PMID 7934856.

- ^ a b c Mojica FJ, Montoliu L (2016). "On the Origin of CRISPR-Cas Technology: From Prokaryotes to Mammals". Trends in Microbiology. 24 (10): 811–820. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.06.005. PMID 27401123.

- ^ a b Mojica FJ, Rodriguez-Valera F (2016). "The discovery of CRISPR in archaea and bacteria". The FEBS Journal. 283 (17): 3162–3169. doi:10.1111/febs.13766. hdl:10045/57676. PMID 27234458.

- ^ Mojica FJ, Díez-Villaseñor C, Soria E, Juez G (April 2000). "Biological significance of a family of regularly spaced repeats in the genomes of Archaea, Bacteria and mitochondria". Molecular Microbiology. 36 (1): 244–246. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01838.x. PMID 10760181.

- ^ Isaacson W (2021). The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-9821-1585-2. OCLC 1239982737. Archived from the original on 2023-01-14. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Barrangou R, van der Oost J (2013). CRISPR-Cas Systems: RNA-mediated Adaptive Immunity in Bacteria and Archaea. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-642-34656-9.

- ^ Tang TH, Bachellerie JP, Rozhdestvensky T, Bortolin ML, Huber H, Drungowski M, et al. (May 2002). "Identification of 86 candidates for small non-messenger RNAs from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (11): 7536–7541. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.7536T. doi:10.1073/pnas.112047299. PMC 124276. PMID 12032318.

- ^ Charpentier E, Richter H, van der Oost J, White MF (May 2015). "Biogenesis pathways of RNA guides in archaeal and bacterial CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 39 (3): 428–441. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuv023. PMC 5965381. PMID 25994611.

- ^ Romero DA, Magill D, Millen A, Horvath P, Fremaux C (November 2020). "Dairy lactococcal and streptococcal phage-host interactions: an industrial perspective in an evolving phage landscape". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 44 (6): 909–932. doi:10.1093/femsre/fuaa048. PMID 33016324.

- ^ Molteni M, Huckins G (1 August 2020). "The WIRED Guide to Crispr". Condé Nast. Wired Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Jansen R, Embden JD, Gaastra W, Schouls LM (March 2002). "Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes". Molecular Microbiology. 43 (6): 1565–1575. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. PMID 11952905.

- ^ a b Horvath P, Barrangou R (January 2010). "CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea". Science. 327 (5962): 167–170. Bibcode:2010Sci...327..167H. doi:10.1126/Science.1179555. PMID 20056882.

- ^ a b Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ (March 2010). "CRISPR interference: RNA-directed adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea". Nature Reviews Genetics. 11 (3): 181–190. doi:10.1038/nrg2749. PMC 2928866. PMID 20125085.

- ^ Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C (May 2007). "The CRISPRdb database and tools to display CRISPRs and to generate dictionaries of spacers and repeats". BMC Bioinformatics. 8 172. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-172. PMC 1892036. PMID 17521438.

- ^ a b Pourcel C, Salvignol G, Vergnaud G (March 2005). "CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies". Microbiology. 151 (Pt 3): 653–663. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27437-0. PMID 15758212.

- ^ a b Mojica FJ, Díez-Villaseñor C, García-Martínez J, Soria E (February 2005). "Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 60 (2): 174–182. Bibcode:2005JMolE..60..174M. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. PMID 15791728.

- ^ a b Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD (August 2005). "Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin". Microbiology. 151 (Pt 8): 2551–2561. doi:10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. PMID 16079334.

- ^ Morange M (June 2015). "What history tells us XXXVII. CRISPR-Cas: The discovery of an immune system in prokaryotes". Journal of Biosciences. 40 (2): 221–223. doi:10.1007/s12038-015-9532-6. PMID 25963251.

- ^ Lander ES (January 2016). "The Heroes of CRISPR". Cell. 164 (1–2): 18–28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.041. PMID 26771483.

- ^ Makarova KS, Grishin NV, Shabalina SA, Wolf YI, Koonin EV (March 2006). "A putative RNA-interference-based immune system in prokaryotes: computational analysis of the predicted enzymatic machinery, functional analogies with eukaryotic RNAi, and hypothetical mechanisms of action". Biology Direct. 1 7. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-7. PMC 1462988. PMID 16545108.

- ^ Pennisi E (August 2013). "The CRISPR craze". News Focus. Science. 341 (6148): 833–836. Bibcode:2013Sci...341..833P. doi:10.1126/science.341.6148.833. PMID 23970676.

- ^ a b c Marraffini LA (October 2015). "CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes". Nature. 526 (7571): 55–61. Bibcode:2015Natur.526...55M. doi:10.1038/nature15386. PMID 26432244.

- ^ Brouns SJ, Jore MM, Lundgren M, Westra ER, Slijkhuis RJ, Snijders AP, et al. (August 2008). "Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes". Science. 321 (5891): 960–964. Bibcode:2008Sci...321..960B. doi:10.1126/science.1159689. PMC 5898235. PMID 18703739.

- ^ a b Garneau JE, Dupuis MÈ, Villion M, Romero DA, Barrangou R, Boyaval P, et al. (November 2010). "The CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system cleaves bacteriophage and plasmid DNA". Nature. 468 (7320): 67–71. Bibcode:2010Natur.468...67G. doi:10.1038/nature09523. PMID 21048762.

- ^ Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E (August 2012). "A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity". Science. 337 (6096): 816–821. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..816J. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. PMC 6286148. PMID 22745249.

- ^ Mojica FJ, Montoliu L (2016). "On the Origin of CRISPR-Cas Technology: From Prokaryotes to Mammals". Trends in Microbiology. 24 (10): 811–820. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.06.005. PMID 27401123.

- ^ Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, et al. (February 2013). "Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems". Science. 339 (6121): 819–823. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..819C. doi:10.1126/science.1231143. PMC 3795411. PMID 23287718.

- ^ Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, et al. (February 2013). "RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9". Science. 339 (6121): 823–826. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..823M. doi:10.1126/science.1232033. PMC 3712628. PMID 23287722.

- ^ Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, et al. (May 2015). "CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes". Protein & Cell. 6 (5): 363–372. doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. PMC 4417674. PMID 25894090.

- ^ a b Deltcheva E, Chylinski K, Sharma CM, Gonzales K, Chao Y, Pirzada ZA, et al. (March 2011). "CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III". Nature. 471 (7340): 602–607. Bibcode:2011Natur.471..602D. doi:10.1038/nature09886. PMC 3070239. PMID 21455174.

- ^ Barrangou R (November 2015). "Diversity of CRISPR-Cas immune systems and molecular machines". Genome Biology. 16 247. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0816-9. PMC 4638107. PMID 26549499.

- ^ Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E (August 2012). "A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity". Science. 337 (6096): 816–821. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..816J. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. PMC 6286148. PMID 22745249.

- ^ Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, et al. (February 2013). "Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems". Science. 339 (6121): 819–823. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..819C. doi:10.1126/science.1231143. PMC 3795411. PMID 23287718.

- ^ Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, et al. (February 2013). "RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9". Science. 339 (6121): 823–826. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..823M. doi:10.1126/science.1232033. PMC 3712628. PMID 23287722.

- ^ Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Konermann S, Joung J, Slaymaker IM, Cox DB, et al. (August 2016). "C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector". Science. 353 (6299) aaf5573. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5573. PMC 5127784. PMID 27256883.

- ^ Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Lee JW, Essletzbichler P, Dy AJ, Joung J, et al. (April 2017). "Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2". Science. 356 (6336): 438–442. Bibcode:2017Sci...356..438G. doi:10.1126/science.aam9321. PMC 5526198. PMID 28408723.

- ^ Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Kellner MJ, Joung J, Collins JJ, Zhang F (April 2018). "Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6". Science. 360 (6387): 439–444. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..439G. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0179. PMC 5961727. PMID 29449508.

- ^ Iwasaki RS, Batey RT (September 2020). "SPRINT: a Cas13a-based platform for detection of small molecules". Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (17): e101. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa673. PMC 7515716. PMID 32797156.

- ^ Hille F, Charpentier E (November 2016). "CRISPR-Cas: biology, mechanisms and relevance". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1707) 20150496. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0496. PMC 5052741. PMID 27672148.

- ^ a b c Barrangou R, Marraffini LA (April 2014). "CRISPR-Cas systems: Prokaryotes upgrade to adaptive immunity". Molecular Cell. 54 (2): 234–244. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.011. PMC 4025954. PMID 24766887.

- ^ a b c Tyson GW, Banfield JF (January 2008). "Rapidly evolving CRISPRs implicated in acquired resistance of microorganisms to viruses". Environmental Microbiology. 10 (1): 200–207. Bibcode:2008EnvMi..10..200T. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01444.x. PMID 17894817.

- ^ a b Koonin EV, Makarova KS (May 2019). "Origins and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 374 (1772) 20180087. doi:10.1098/rstb.2018.0087. PMC 6452270. PMID 30905284.

- ^ a b c Wright AV, Nuñez JK, Doudna JA (January 2016). "Biology and Applications of CRISPR Systems: Harnessing Nature's Toolbox for Genome Engineering". Cell. 164 (1–2): 29–44. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.035. PMID 26771484.

- ^ Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Iranzo J, Shmakov SA, Alkhnbashi OS, Brouns SJ, et al. (December 2019). "Evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 18 (1): 67–83. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x. hdl:10045/102627. PMC 8905525. PMID 31857715.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Alkhnbashi OS, Costa F, Shah SA, Saunders SJ, et al. (November 2015). "An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 13 (11): 722–736. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3569. PMC 5426118. PMID 26411297.

- ^ a b c Wiedenheft B, Sternberg SH, Doudna JA (February 2012). "RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea". Nature. 482 (7385): 331–338. Bibcode:2012Natur.482..331W. doi:10.1038/nature10886. PMID 22337052.

- ^ a b Deng L, Garrett RA, Shah SA, Peng X, She Q (March 2013). "A novel interference mechanism by a type IIIB CRISPR-Cmr module in Sulfolobus". Molecular Microbiology. 87 (5): 1088–1099. doi:10.1111/mmi.12152. PMID 23320564.

- ^ Sinkunas T, Gasiunas G, Fremaux C, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V (April 2011). "Cas3 is a single-stranded DNA nuclease and ATP-dependent helicase in the CRISPR/Cas immune system". The EMBO Journal. 30 (7): 1335–1342. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.41. PMC 3094125. PMID 21343909.

- ^ Huo Y, Nam KH, Ding F, Lee H, Wu L, Xiao Y, et al. (September 2014). "Structures of CRISPR Cas3 offer mechanistic insights into Cascade-activated DNA unwinding and degradation". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 21 (9): 771–777. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2875. PMC 4156918. PMID 25132177.

- ^ Brendel J, Stoll B, Lange SJ, Sharma K, Lenz C, Stachler AE, et al. (March 2014). "A complex of Cas proteins 5, 6, and 7 is required for the biogenesis and stability of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (crispr)-derived rnas (crrnas) in Haloferax volcanii". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 289 (10): 7164–77. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.508184. PMC 3945376. PMID 24459147.

- ^ a b Chylinski K, Makarova KS, Charpentier E, Koonin EV (June 2014). "Classification and evolution of type II CRISPR-Cas systems". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (10): 6091–6105. doi:10.1093/nar/gku241. PMC 4041416. PMID 24728998.

- ^ a b Makarova KS, Aravind L, Wolf YI, Koonin EV (July 2011). "Unification of Cas protein families and a simple scenario for the origin and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems". Biology Direct. 6 38. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-38. PMC 3150331. PMID 21756346.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Iranzo J, Shmakov SA, Alkhnbashi OS, Brouns SJ, et al. (February 2020). "Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 18 (2): 67–83. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x. hdl:10045/102627. PMC 8905525. PMID 31857715.

- ^ a b Mogila I, Kazlauskiene M, Valinskyte S, Tamulaitiene G, Tamulaitis G, Siksnys V (March 2019). "Genetic Dissection of the Type III-A CRISPR-Cas System Csm Complex Reveals Roles of Individual Subunits". Cell Reports. 26 (10): 2753–2765.e4. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.029. PMID 30840895.

- ^ a b c Gasiunas G, Barrangou R, Horvath P, Siksnys V (September 2012). "Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (39): E2579–2586. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E2579G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208507109. PMC 3465414. PMID 22949671.

- ^ Heler R, Samai P, Modell JW, Weiner C, Goldberg GW, Bikard D, et al. (March 2015). "Cas9 specifies functional viral targets during CRISPR-Cas adaptation". Nature. 519 (7542): 199–202. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..199H. doi:10.1038/nature14245. PMC 4385744. PMID 25707807.

- ^ Nam KH, Kurinov I, Ke A (September 2011). "Crystal structure of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated Csn2 protein revealed Ca2+-dependent double-stranded DNA binding activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286 (35): 30759–30768. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.256263. PMC 3162437. PMID 21697083.

- ^ Lee H, Dhingra Y, Sashital DG (April 2019). "The Cas4-Cas1-Cas2 complex mediates precise prespacer processing during CRISPR adaptation". eLife. 8 e44248. doi:10.7554/eLife.44248. PMC 6519985. PMID 31021314.

- ^ Chylinski K, Le Rhun A, Charpentier E (May 2013). "The tracrRNA and Cas9 families of type II CRISPR-Cas immunity systems". RNA Biology. 10 (5): 726–737. doi:10.4161/rna.24321. PMC 3737331. PMID 23563642.

- ^ Makarova KS, Zhang F, Koonin EV (January 2017). "SnapShot: Class 2 CRISPR-Cas Systems". Cell. 168 (1–2): 328–328.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.038. PMID 28086097.

- ^ Paul B, Montoya G (February 2020). "CRISPR-Cas12a: Functional overview and applications". Biomedical Journal. 43 (1): 8–17. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2019.10.005. PMC 7090318. PMID 32200959.

- ^ Cox DB, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Franklin B, Kellner MJ, Joung J, et al. (November 2017). "RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13". Science. 358 (6366): 1019–1027. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1019C. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0180. PMC 5793859. PMID 29070703.

- ^ a b Xu C, Zhou Y, Xiao Q, He B, Geng G, Wang Z, et al. (May 2021). "Programmable RNA editing with compact CRISPR-Cas13 systems from uncultivated microbes". Nature Methods. 18 (5): 499–506. doi:10.1038/s41592-021-01124-4. PMID 33941935.

- ^ Azangou-Khyavy M, Ghasemi M, Khanali J, Boroomand-Saboor M, Jamalkhah M, Soleimani M, et al. (2020). "CRISPR/Cas: From Tumor Gene Editing to T Cell-Based Immunotherapy of Cancer". Frontiers in Immunology. 11 2062. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.02062. PMC 7553049. PMID 33117331.

- ^ a b Aliyari R, Ding SW (January 2009). "RNA-based viral immunity initiated by the Dicer family of host immune receptors". Immunological Reviews. 227 (1): 176–188. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00722.x. PMC 2676720. PMID 19120484.

- ^ Dugar G, Herbig A, Förstner KU, Heidrich N, Reinhardt R, Nieselt K, et al. (May 2013). "High-resolution transcriptome maps reveal strain-specific regulatory features of multiple Campylobacter jejuni isolates". PLOS Genetics. 9 (5) e1003495. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003495. PMC 3656092. PMID 23696746.

- ^ Hatoum-Aslan A, Maniv I, Marraffini LA (December 2011). "Mature clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats RNA (crRNA) length is measured by a ruler mechanism anchored at the precursor processing site". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (52): 21218–21222. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10821218H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112832108. PMC 3248500. PMID 22160698.

- ^ a b Yosef I, Goren MG, Qimron U (July 2012). "Proteins and DNA elements essential for the CRISPR adaptation process in Escherichia coli". Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (12): 5569–5576. doi:10.1093/nar/gks216. PMC 3384332. PMID 22402487.

- ^ a b c d Swarts DC, Mosterd C, van Passel MW, Brouns SJ (2012). "CRISPR interference directs strand specific spacer acquisition". PLOS ONE. 7 (4) e35888. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735888S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035888. PMC 3338789. PMID 22558257.

- ^ Babu M, Beloglazova N, Flick R, Graham C, Skarina T, Nocek B, et al. (January 2011). "A dual function of the CRISPR-Cas system in bacterial antivirus immunity and DNA repair". Molecular Microbiology. 79 (2): 484–502. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07465.x. PMC 3071548. PMID 21219465.

- ^ Han D, Lehmann K, Krauss G (June 2009). "SSO1450—a CAS1 protein from Sulfolobus solfataricus P2 with high affinity for RNA and DNA". FEBS Letters. 583 (12): 1928–1932. Bibcode:2009FEBSL.583.1928H. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.047. PMID 19427858.

- ^ Wiedenheft B, Zhou K, Jinek M, Coyle SM, Ma W, Doudna JA (June 2009). "Structural basis for DNase activity of a conserved protein implicated in CRISPR-mediated genome defense". Structure. 17 (6): 904–912. doi:10.1016/j.str.2009.03.019. PMID 19523907.

- ^ Beloglazova N, Brown G, Zimmerman MD, Proudfoot M, Makarova KS, Kudritska M, et al. (July 2008). "A novel family of sequence-specific endoribonucleases associated with the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (29): 20361–20371. doi:10.1074/jbc.M803225200. PMC 2459268. PMID 18482976.

- ^ Samai P, Smith P, Shuman S (December 2010). "Structure of a CRISPR-associated protein Cas2 from Desulfovibrio vulgaris". Acta Crystallographica Section F. 66 (Pt 12): 1552–1556. doi:10.1107/S1744309110039801. PMC 2998353. PMID 21139194.

- ^ Nam KH, Ding F, Haitjema C, Huang Q, DeLisa MP, Ke A (October 2012). "Double-stranded endonuclease activity in Bacillus halodurans clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated Cas2 protein". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (43): 35943–35952. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.382598. PMC 3476262. PMID 22942283.

- ^ a b Nuñez JK, Kranzusch PJ, Noeske J, Wright AV, Davies CW, Doudna JA (June 2014). "Cas1-Cas2 complex formation mediates spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 21 (6): 528–534. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2820. PMC 4075942. PMID 24793649.

- ^ Nuñez JK, Lee AS, Engelman A, Doudna JA (March 2015). "Integrase-mediated spacer acquisition during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity". Nature. 519 (7542): 193–198. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..193N. doi:10.1038/nature14237. PMC 4359072. PMID 25707795.

- ^ Wang J, Li J, Zhao H, Sheng G, Wang M, Yin M, et al. (November 2015). "Structural and Mechanistic Basis of PAM-Dependent Spacer Acquisition in CRISPR-Cas Systems". Cell. 163 (4): 840–853. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.008. PMID 26478180.

- ^ Nuñez JK, Harrington LB, Kranzusch PJ, Engelman AN, Doudna JA (November 2015). "Foreign DNA capture during CRISPR-Cas adaptive immunity". Nature. 527 (7579): 535–538. Bibcode:2015Natur.527..535N. doi:10.1038/nature15760. PMC 4662619. PMID 26503043.

- ^ Sorek R, Lawrence CM, Wiedenheft B (2013). "CRISPR-mediated adaptive immune systems in bacteria and archaea". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 82 (1): 237–266. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-072911-172315. PMID 23495939.

- ^ Nuñez JK, Bai L, Harrington LB, Hinder TL, Doudna JA (June 2016). "CRISPR Immunological Memory Requires a Host Factor for Specificity". Molecular Cell. 62 (6): 824–833. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.027. PMID 27211867.

- ^ Fagerlund RD, Wilkinson ME, Klykov O, Barendregt A, Pearce FG, Kieper SN, et al. (June 2017). "Spacer capture and integration by a type I-F Cas1-Cas2–3 CRISPR adaptation complex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (26): E5122 – E5128. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114E5122F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1618421114. PMC 5495228. PMID 28611213.

- ^ Rollie C, Graham S, Rouillon C, White MF (February 2018). "Prespacer processing and specific integration in a Type I-A CRISPR system". Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (3): 1007–1020. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx1232. PMC 5815122. PMID 29228332.

- ^ a b c d Horvath P, Romero DA, Coûté-Monvoisin AC, Richards M, Deveau H, Moineau S, et al. (February 2008). "Diversity, activity, and evolution of CRISPR loci in Streptococcus thermophilus". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (4): 1401–1412. doi:10.1128/JB.01415-07. PMC 2238196. PMID 18065539.

- ^ a b c Deveau H, Barrangou R, Garneau JE, Labonté J, Fremaux C, Boyaval P, et al. (February 2008). "Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (4): 1390–1400. doi:10.1128/JB.01412-07. PMC 2238228. PMID 18065545.

- ^ Mojica FJ, Díez-Villaseñor C, García-Martínez J, Almendros C (March 2009). "Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system". Microbiology. 155 (Pt 3): 733–740. doi:10.1099/mic.0.023960-0. PMID 19246744.

- ^ a b Lillestøl RK, Shah SA, Brügger K, Redder P, Phan H, Christiansen J, et al. (April 2009). "CRISPR families of the crenarchaeal genus Sulfolobus: bidirectional transcription and dynamic properties". Molecular Microbiology. 72 (1): 259–272. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06641.x. PMID 19239620.

- ^ a b Shah SA, Hansen NR, Garrett RA (February 2009). "Distribution of CRISPR spacer matches in viruses and plasmids of crenarchaeal acidothermophiles and implications for their inhibitory mechanism". Biochemical Society Transactions. 37 (Pt 1): 23–28. doi:10.1042/BST0370023. PMID 19143596.

- ^ a b Díez-Villaseñor C, Guzmán NM, Almendros C, García-Martínez J, Mojica FJ (May 2013). "CRISPR-spacer integration reporter plasmids reveal distinct genuine acquisition specificities among CRISPR-Cas I-E variants of Escherichia coli". RNA Biology. 10 (5): 792–802. doi:10.4161/rna.24023. PMC 3737337. PMID 23445770.

- ^ a b c Erdmann S, Garrett RA (September 2012). "Selective and hyperactive uptake of foreign DNA by adaptive immune systems of an archaeon via two distinct mechanisms". Molecular Microbiology. 85 (6): 1044–1056. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08171.x. PMC 3468723. PMID 22834906.

- ^ a b Shah SA, Erdmann S, Mojica FJ, Garrett RA (May 2013). "Protospacer recognition motifs: mixed identities and functional diversity". RNA Biology. 10 (5): 891–899. doi:10.4161/rna.23764. PMC 3737346. PMID 23403393.

- ^ Andersson AF, Banfield JF (May 2008). "Virus population dynamics and acquired virus resistance in natural microbial communities". Science. 320 (5879): 1047–1050. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1047A. doi:10.1126/science.1157358. PMID 18497291.

- ^ a b c d Pride DT, Sun CL, Salzman J, Rao N, Loomer P, Armitage GC, et al. (January 2011). "Analysis of streptococcal CRISPRs from human saliva reveals substantial sequence diversity within and between subjects over time". Genome Research. 21 (1): 126–136. doi:10.1101/gr.111732.110. PMC 3012920. PMID 21149389.

- ^ a b Goren MG, Yosef I, Auster O, Qimron U (October 2012). "Experimental definition of a clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic duplicon in Escherichia coli". Journal of Molecular Biology. 423 (1): 14–16. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.037. PMID 22771574.

- ^ a b c Datsenko KA, Pougach K, Tikhonov A, Wanner BL, Severinov K, Semenova E (July 2012). "Molecular memory of prior infections activates the CRISPR/Cas adaptive bacterial immunity system". Nature Communications. 3 945. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..945D. doi:10.1038/ncomms1937. PMID 22781758.

- ^ Gesner EM, Schellenberg MJ, Garside EL, George MM, Macmillan AM (June 2011). "Recognition and maturation of effector RNAs in a CRISPR interference pathway". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 18 (6): 688–692. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2042. PMID 21572444.

- ^ Sashital DG, Jinek M, Doudna JA (June 2011). "An RNA-induced conformational change required for CRISPR RNA cleavage by the endoribonuclease Cse3". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 18 (6): 680–687. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2043. PMID 21572442.

- ^ Haurwitz RE, Jinek M, Wiedenheft B, Zhou K, Doudna JA (September 2010). "Sequence- and structure-specific RNA processing by a CRISPR endonuclease". Science. 329 (5997): 1355–1358. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1355H. doi:10.1126/science.1192272. PMC 3133607. PMID 20829488.

- ^ a b Kunin V, Sorek R, Hugenholtz P (2007). "Evolutionary conservation of sequence and secondary structures in CRISPR repeats". Genome Biology. 8 (4) R61. doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r61. PMC 1896005. PMID 17442114.

- ^ Carte J, Wang R, Li H, Terns RM, Terns MP (December 2008). "Cas6 is an endoribonuclease that generates guide RNAs for invader defense in prokaryotes". Genes & Development. 22 (24): 3489–3496. doi:10.1101/gad.1742908. PMC 2607076. PMID 19141480.

- ^ Wang R, Preamplume G, Terns MP, Terns RM, Li H (February 2011). "Interaction of the Cas6 riboendonuclease with CRISPR RNAs: recognition and cleavage". Structure. 19 (2): 257–264. doi:10.1016/j.str.2010.11.014. PMC 3154685. PMID 21300293.

- ^ Niewoehner O, Jinek M, Doudna JA (January 2014). "Evolution of CRISPR RNA recognition and processing by Cas6 endonucleases". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (2): 1341–1353. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt922. PMC 3902920. PMID 24150936.

- ^ Semenova E, Jore MM, Datsenko KA, Semenova A, Westra ER, Wanner B, et al. (June 2011). "Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (25): 10098–10103. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810098S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104144108. PMC 3121866. PMID 21646539.

- ^ Gudbergsdottir S, Deng L, Chen Z, Jensen JV, Jensen LR, She Q, et al. (January 2011). "Dynamic properties of the Sulfolobus CRISPR/Cas and CRISPR/Cmr systems when challenged with vector-borne viral and plasmid genes and protospacers". Molecular Microbiology. 79 (1): 35–49. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07452.x. PMC 3025118. PMID 21166892.

- ^ Manica A, Zebec Z, Teichmann D, Schleper C (April 2011). "In vivo activity of CRISPR-mediated virus defence in a hyperthermophilic archaeon". Molecular Microbiology. 80 (2): 481–491. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07586.x. PMID 21385233.

- ^ Jore MM, Lundgren M, van Duijn E, Bultema JB, Westra ER, Waghmare SP, et al. (May 2011). "Structural basis for CRISPR RNA-guided DNA recognition by Cascade" (PDF). Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 18 (5): 529–536. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2019. PMID 21460843.

- ^ Wiedenheft B, Lander GC, Zhou K, Jore MM, Brouns SJ, van der Oost J, et al. (September 2011). "Structures of the RNA-guided surveillance complex from a bacterial immune system". Nature. 477 (7365): 486–489. Bibcode:2011Natur.477..486W. doi:10.1038/nature10402. PMC 4165517. PMID 21938068.

- ^ Zhang J, Rouillon C, Kerou M, Reeks J, Brugger K, Graham S, et al. (February 2012). "Structure and mechanism of the CMR complex for CRISPR-mediated antiviral immunity". Molecular Cell. 45 (3): 303–313. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.013. PMC 3381847. PMID 22227115.

- ^ a b Hale CR, Zhao P, Olson S, Duff MO, Graveley BR, Wells L, et al. (November 2009). "RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA-Cas protein complex". Cell. 139 (5): 945–956. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.040. PMC 2951265. PMID 19945378.

- ^ Estrella MA, Kuo FT, Bailey S (2016). "RNA-activated DNA cleavage by the Type III-B CRISPR–Cas effector complex". Genes & Development. 30 (4): 460–470. doi:10.1101/gad.273722.115. PMC 4762430. PMID 26848046.

- ^ Samai P, Pyenson N, Jiang W, Goldberg GW, Hatoum-Aslan A, Marraffini LA (2015). "Co-transcriptional DNA and RNA Cleavage during Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity". Cell. 161 (5): 1164–1174. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.027. PMC 4594840. PMID 25959775.

- ^ a b c Marraffini LA, Sontheimer EJ (January 2010). "Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity". Nature. 463 (7280): 568–571. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..568M. doi:10.1038/nature08703. PMC 2813891. PMID 20072129.

- ^ Krupovic M, Béguin P, Koonin EV (August 2017). "Casposons: mobile genetic elements that gave rise to the CRISPR-Cas adaptation machinery". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 38: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2017.04.004. PMC 5665730. PMID 28472712.

- ^ Koonin EV, Makarova KS (May 2013). "CRISPR-Cas: evolution of an RNA-based adaptive immunity system in prokaryotes". RNA Biology. 10 (5): 679–686. doi:10.4161/rna.24022. PMC 3737325. PMID 23439366.

- ^ Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Zhang F (June 2017). "Diversity, classification and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 37: 67–78. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2017.05.008. PMC 5776717. PMID 28605718.

- ^ a b Shmakov S, Smargon A, Scott D, Cox D, Pyzocha N, Yan W, et al. (March 2017). "Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 15 (3): 169–182. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.184. PMC 5851899. PMID 28111461.

- ^ Kupczok A, Bollback JP (February 2013). "Probabilistic models for CRISPR spacer content evolution". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (1) 54. Bibcode:2013BMCEE..13...54K. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-54. PMC 3704272. PMID 23442002.

- ^ Sternberg SH, Richter H, Charpentier E, Qimron U (March 2016). "Adaptation in CRISPR-Cas Systems". Molecular Cell. 61 (6): 797–808. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.030. hdl:21.11116/0000-0003-E74E-2. PMID 26949040.

- ^ Koonin EV, Wolf YI (November 2009). "Is evolution Darwinian or/and Lamarckian?". Biology Direct. 4: 42. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-4-42. PMC 2781790. PMID 19906303.

- ^ Weiss A (October 2015). "Lamarckian Illusions". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 30 (10): 566–568. Bibcode:2015TEcoE..30..566W. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2015.08.003. PMID 26411613.

- ^ a b Koonin EV, Wolf YI (February 2016). "Just how Lamarckian is CRISPR-Cas immunity: the continuum of evolvability mechanisms". Biology Direct. 11 (1) 9. doi:10.1186/s13062-016-0111-z. PMC 4765028. PMID 26912144.

- ^ Heidelberg JF, Nelson WC, Schoenfeld T, Bhaya D (2009). Ahmed N (ed.). "Germ warfare in a microbial mat community: CRISPRs provide insights into the co-evolution of host and viral genomes". PLOS ONE. 4 (1) e4169. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4169H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004169. PMC 2612747. PMID 19132092.

- ^ Touchon M, Rocha EP (June 2010). Randau L (ed.). "The small, slow and specialized CRISPR and anti-CRISPR of Escherichia and Salmonella". PLOS ONE. 5 (6) e11126. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511126T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011126. PMC 2886076. PMID 20559554.

- ^ a b c Rho M, Wu YW, Tang H, Doak TG, Ye Y (2012). "Diverse CRISPRs evolving in human microbiomes". PLOS Genetics. 8 (6) e1002441. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002441. PMC 3374615. PMID 22719260.

- ^ a b Sun CL, Barrangou R, Thomas BC, Horvath P, Fremaux C, Banfield JF (February 2013). "Phage mutations in response to CRISPR diversification in a bacterial population". Environmental Microbiology. 15 (2): 463–470. Bibcode:2013EnvMi..15..463S. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02879.x. PMID 23057534.

- ^ Kuno S, Sako Y, Yoshida T (May 2014). "Diversification of CRISPR within coexisting genotypes in a natural population of the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa". Microbiology. 160 (Pt 5): 903–916. doi:10.1099/mic.0.073494-0. PMID 24586036.

- ^ Sorek R, Kunin V, Hugenholtz P (March 2008). "CRISPR—a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 6 (3): 181–186. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1793. OSTI 926489. PMID 18157154.

Table 1: Web resources for CRISPR analysis

- ^ Pride DT, Salzman J, Relman DA (September 2012). "Comparisons of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and viromes in human saliva reveal bacterial adaptations to salivary viruses". Environmental Microbiology. 14 (9): 2564–2576. Bibcode:2012EnvMi..14.2564P. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02775.x. PMC 3424356. PMID 22583485.

- ^ Held NL, Herrera A, Whitaker RJ (November 2013). "Reassortment of CRISPR repeat-spacer loci in Sulfolobus islandicus". Environmental Microbiology. 15 (11): 3065–3076. Bibcode:2013EnvMi..15.3065H. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.12146. PMID 23701169.

- ^ Held NL, Herrera A, Cadillo-Quiroz H, Whitaker RJ (September 2010). "CRISPR associated diversity within a population of Sulfolobus islandicus". PLOS ONE. 5 (9) e12988. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512988H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012988. PMC 2946923. PMID 20927396.

- ^ a b c Medvedeva S, Liu Y, Koonin EV, Severinov K, Prangishvili D, Krupovic M (November 2019). "Virus-borne mini-CRISPR arrays are involved in interviral conflicts". Nature Communications. 10 (1) 5204. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.5204M. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13205-2. PMC 6858448. PMID 31729390.

- ^ Skennerton CT, Imelfort M, Tyson GW (May 2013). "Crass: identification and reconstruction of CRISPR from unassembled metagenomic data". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (10): e105. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt183. PMC 3664793. PMID 23511966.

- ^ Stern A, Mick E, Tirosh I, Sagy O, Sorek R (October 2012). "CRISPR targeting reveals a reservoir of common phages associated with the human gut microbiome". Genome Research. 22 (10): 1985–1994. doi:10.1101/gr.138297.112. PMC 3460193. PMID 22732228.

- ^ Novick RP, Christie GE, Penadés JR (August 2010). "The phage-related chromosomal islands of Gram-positive bacteria". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 8 (8): 541–551. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2393. PMC 3522866. PMID 20634809.

- ^ Ram G, Chen J, Kumar K, Ross HF, Ubeda C, Damle PK, et al. (October 2012). "Staphylococcal pathogenicity island interference with helper phage reproduction is a paradigm of molecular parasitism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (40): 16300–16305. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10916300R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204615109. PMC 3479557. PMID 22991467.

- ^ Ram G, Chen J, Ross HF, Novick RP (October 2014). "Precisely modulated pathogenicity island interference with late phage gene transcription". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (40): 14536–14541. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11114536R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1406749111. PMC 4209980. PMID 25246539.

- ^ Seed KD, Lazinski DW, Calderwood SB, Camilli A (February 2013). "A bacteriophage encodes its own CRISPR/Cas adaptive response to evade host innate immunity". Nature. 494 (7438): 489–491. Bibcode:2013Natur.494..489S. doi:10.1038/nature11927. PMC 3587790. PMID 23446421.

- ^ Boyd CM, Angermeyer A, Hays SG, Barth ZK, Patel KM, Seed KD (September 2021). "Bacteriophage ICP1: A Persistent Predator of Vibrio cholerae". Annual Review of Virology. 8 (1): 285–304. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-091919-072020. ISSN 2327-056X. PMC 9040626. PMID 34314595.

- ^ a b Koblan LW, Liu DR, Anzalone AV (July 2020). "Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors". Nature Biotechnology. 38 (7): 824–844. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0561-9. ISSN 1546-1696. PMID 32572269.

- ^ Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, et al. (December 2019). "Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA". Nature. 576 (7785): 149–157. Bibcode:2019Natur.576..149A. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 6907074. PMID 31634902.

- ^ Feng Q, Li Q, Zhou H, Wang Z, Lin C, Jiang Z, et al. (August 2024). "CRISPR technology in human diseases". MedComm. 5 (8) e672. doi:10.1002/mco2.672. PMC 11286548. PMID 39081515.

- ^ Li T, Li S, Kang Y, Zhou J, Yi M (August 2024). "Harnessing the evolving CRISPR/Cas9 for precision oncology". Journal of Translational Medicine. 22 (1) 749. doi:10.1186/s12967-024-05570-4. PMC 11312220. PMID 39118151.