Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Turkey shoot

View on Wikipedia

A turkey shoot is a sport shooting event featuring marksmanship competitions, with turkeys as prizes. Originally, the turkeys were themselves restrained and put in place to serve as the targets, while modern versions employ standard paper targets. "Turkey shoot" is also in common use as an idiomatic term for an extremely one-sided battle or contest.[1]

Sport usage

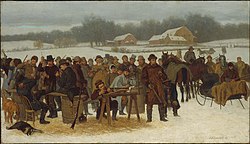

[edit]Turkey shoots in America date back at least to the early 19th century. James Fenimore Cooper's The Pioneers (1823) prominently depicts one, describing it as an "ancient amusement" associated with Christmas.[2] Shoots were common throughout the holiday season, providing birds to adorn dinner tables for Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's Day.[3][4]

In the original format, a live turkey was caged or bound in a stationary position behind a stump or other barrier, with only its head and neck protruding. Contestants, paying a set fee per attempt, vied to land a shot on the bird's exposed parts. The first to do so would immediately claim the prize.[5] Rifles were typically used, at varying ranges depending on the expected skill and number of shooters, but generally between 100 and 200 yards.[6][7]

Over time, concerns arose about the ethics of killing live, restrained animals for sport. This "cruel amusement" was condemned by some Christian speakers as a vice on the same level as "horse-racing, cock-fighting, gouging of eyes, beastly intemperance, profanity, etc."[8] At the urging of Henry Bergh, founder of the ASPCA, some organizers attempted to reduce the birds' suffering by having them humanely slaughtered beforehand, then using their severed heads as the targets.[9] Others moved entirely to a paper target format, where shooters earned their pick from a pool of prize birds in order of their accuracy scores.[4] However, as shoots were locally organized according to custom, and not subject to any central regulation, all three models (live, "dead head", and target) were widely practiced in parallel.[10] Live-turkey shoots persisted into the 20th century, as depicted in the 1941 Gary Cooper film Sergeant York.[11]

Turkey shoots are still popular in the rural United States today.[12] A modern derivation, sometimes more generically known as a meat shoot, is held using shotguns aimed at paper targets about 25–35 yards away. The winner is chosen according to the pellet hole closest to the target's center. The inherent randomness of a shotgun's pellet spray pattern makes this format more approachable for inexperienced shooters.[13]

Military usage

[edit]In military situations, a turkey shoot occurs when a one side outguns the other to the point of the battle being extremely lopsided, as in the following famous examples:

- Battle of New Orleans – War of 1812

- Battle of San Jacinto – Texas Revolution

- Charge of the Light Brigade – Crimean War

- Battle of the Crater – American Civil War

- The Battle of the Philippine Sea during World War II was nicknamed "The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot" due to the disproportionate loss of Japanese planes compared to U.S. ones.[14][15]

- Battle of Longewala – Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

- Operation Mole Cricket 19 during the 1982 Lebanon War was known as the "Bekaa Valley Turkey Shoot" due to the air dominance of the Israeli Air Force during the engagement.[16]

- The Highway of Death during the Gulf War was discussed as a "turkey shoot" due to the extreme destruction wreaked on the fleeing Iraqi convoy.[17]

- Battle of Fallujah (2016) – Iraqi Civil War (2014–2017)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Turkey shoot". Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ Cooper, James Fenimoore (1823). . – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Thanksgiving Universal". Forest and Stream. Vol. 11, no. 17. The Forest and Stream Publishing Company. 1878-11-28.

- ^ a b "For a New Year's Gobbler and the Gold Badge". The New Orleans Daily Democrat. 1877-12-31. p. 1.

- ^ Smith, Andrew F. (2006). The Turkey. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-252-03163-2.

- ^ "The Turkey Shooting Match". Helena Weekly Herald. 1873-10-30. p. 7.

- ^ "Turkey Shooting". Daily Press and Dakotaian. 1875-11-26. p. 4.

- ^ "The Shooting Match". The Boston Recorder. 1821-12-22.

- ^ "Mr. Bergh and Turkey Shooting". Forest and Stream. Vol. 5, no. 15. The Forest and Stream Publishing Company. 1875-12-02.

- ^ "Local Layout". The Livingston Enterprise. 1888-01-07. p. 3.

- ^ Perry, John (2021). Sgt. York His Life, Legend, and Legacy: The Remarkable Story of Sergeant Alvin C. York. Fidelis Publishing. ISBN 9781735856339.

- ^ Braswell, Tommy (2023-10-29). "Turkey shoots are a holiday tradition. Turkeys aren't real, but the fun is". Post and Courier. Archived from the original on 2024-05-07. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Splaine, John (2022-09-17). "What is a "Turkey Shoot?"". Boothbay Register. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Tillman, Barrett (2006-11-07). Clash of the Carriers: The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot of World War II. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 196. ISBN 9781440623998.

- ^ Chambers, John Whiteclay, ed. (1999). The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Oxford University Press. p. 549. ISBN 9780195340921.

- ^ McNabb, James Brian (2017-03-09). A Military History of the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 220. ISBN 9781440829642.

- ^ Atkinson, Rick (1993-10-05). "'A Merciful Clemency': Scenes of Enemy Slaughtered in Retreat Persuaded Powell to Put Brakes On War". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2022-04-17. Retrieved 2024-05-08.