Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Version space learning

View on Wikipedia

Version space learning is a logical approach to machine learning, specifically binary classification. Version space learning algorithms search a predefined space of hypotheses, viewed as a set of logical sentences. Formally, the hypothesis space is a disjunction[1]

(i.e., one or more of hypotheses 1 through n are true). A version space learning algorithm is presented with examples, which it will use to restrict its hypothesis space; for each example x, the hypotheses that are inconsistent with x are removed from the space.[2] This iterative refining of the hypothesis space is called the candidate elimination algorithm, the hypothesis space maintained inside the algorithm, its version space.[1]

The version space algorithm

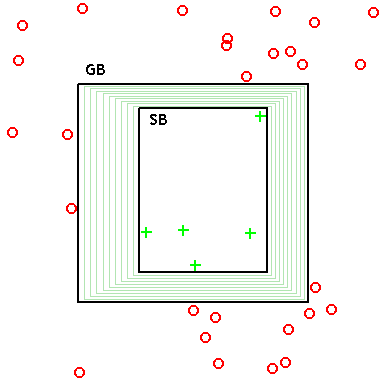

[edit]In settings where there is a generality-ordering on hypotheses, it is possible to represent the version space by two sets of hypotheses: (1) the most specific consistent hypotheses, and (2) the most general consistent hypotheses, where "consistent" indicates agreement with observed data.

The most specific hypotheses (i.e., the specific boundary SB) cover the observed positive training examples, and as little of the remaining feature space as possible. These hypotheses, if reduced any further, exclude a positive training example, and hence become inconsistent. These minimal hypotheses essentially constitute a (pessimistic) claim that the true concept is defined just by the positive data already observed: Thus, if a novel (never-before-seen) data point is observed, it should be assumed to be negative. (I.e., if data has not previously been ruled in, then it's ruled out.)

The most general hypotheses (i.e., the general boundary GB) cover the observed positive training examples, but also cover as much of the remaining feature space without including any negative training examples. These, if enlarged any further, include a negative training example, and hence become inconsistent. These maximal hypotheses essentially constitute a (optimistic) claim that the true concept is defined just by the negative data already observed: Thus, if a novel (never-before-seen) data point is observed, it should be assumed to be positive. (I.e., if data has not previously been ruled out, then it's ruled in.)

Thus, during learning, the version space (which itself is a set – possibly infinite – containing all consistent hypotheses) can be represented by just its lower and upper bounds (maximally general and maximally specific hypothesis sets), and learning operations can be performed just on these representative sets.

After learning, classification can be performed on unseen examples by testing the hypothesis learned by the algorithm. If the example is consistent with multiple hypotheses, a majority vote rule can be applied.[1]

Historical background

[edit]The notion of version spaces was introduced by Mitchell in the early 1980s[2] as a framework for understanding the basic problem of supervised learning within the context of solution search. Although the basic "candidate elimination" search method that accompanies the version space framework is not a popular learning algorithm, there are some practical implementations that have been developed (e.g., Sverdlik & Reynolds 1992, Hong & Tsang 1997, Dubois & Quafafou 2002).

A major drawback of version space learning is its inability to deal with noise: any pair of inconsistent examples can cause the version space to collapse, i.e., become empty, so that classification becomes impossible.[1] One solution of this problem is proposed by Dubois and Quafafou that proposed the Rough Version Space,[3] where rough sets based approximations are used to learn certain and possible hypothesis in the presence of inconsistent data.

See also

[edit]- Formal concept analysis

- Inductive logic programming

- Rough set. [The rough set framework focuses on the case where ambiguity is introduced by an impoverished feature set. That is, the target concept cannot be decisively described because the available feature set fails to disambiguate objects belonging to different categories. The version space framework focuses on the (classical induction) case where the ambiguity is introduced by an impoverished data set. That is, the target concept cannot be decisively described because the available data fails to uniquely pick out a hypothesis. Naturally, both types of ambiguity can occur in the same learning problem.]

- Inductive reasoning. [On the general problem of induction.]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Russell, Stuart; Norvig, Peter (2003) [1995]. Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 683–686. ISBN 978-0137903955.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Tom M. (1982). "Generalization as search". Artificial Intelligence. 18 (2): 203–226. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(82)90040-6.

- ^ Dubois, Vincent; Quafafou, Mohamed (2002). "Concept learning with approximation: Rough version spaces". Rough Sets and Current Trends in Computing: Proceedings of the Third International Conference, RSCTC 2002. Malvern, Pennsylvania. pp. 239–246. doi:10.1007/3-540-45813-1_31.

- Hong, Tzung-Pai; Shian-Shyong Tsang (1997). "A generalized version space learning algorithm for noisy and uncertain data". IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. 9 (2): 336–340. doi:10.1109/69.591457. S2CID 29926783.

- Mitchell, Tom M. (1997). Machine Learning. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

- Sverdlik, W.; Reynolds, R.G. (1992). "Dynamic version spaces in machine learning". Proceedings, Fourth International Conference on Tools with Artificial Intelligence (TAI '92). Arlington, VA. pp. 308–315.

Version space learning

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Principles

Version space learning is a logical, symbolic machine learning technique employed in binary classification tasks to iteratively refine the hypothesis space based on observed training examples. It maintains the set of all hypotheses that are consistent with the training data, thereby narrowing down potential models of the target concept without requiring exhaustive search through the entire hypothesis space. This approach is particularly suited for scenarios where the goal is to learn a target function , with representing the instance space of attribute-value pairs, and hypotheses serving as approximations of .[3] The core principle of version space learning involves representing the version space as the subset comprising all hypotheses in the predefined hypothesis space that correctly classify every training example. Positive examples (labeled 1) and negative examples (labeled 0) are used to eliminate hypotheses inconsistent with the observed data, progressively restricting while preserving all viable candidates. This elimination process ensures that the version space always contains the true target concept, assuming it is expressible within .[3] Version space learning operates under key assumptions of a noise-free environment, where training examples are accurately labeled, and a deterministic target concept that yields consistent classifications for any given instance. These principles enable exact representation of the version space, with the primary mechanism being the candidate elimination algorithm, which efficiently updates the set of consistent hypotheses as new examples arrive.[3]Role in Concept Learning

Version space learning occupies a foundational position within concept learning, a subfield of machine learning dedicated to inferring a target concept c—typically represented as a boolean-valued function—from a set of training examples consisting of positive instances (those belonging to c) and negative instances (those not belonging to c). This approach addresses the core challenge of inductive inference by systematically searching a predefined hypothesis space to identify all candidate concepts consistent with the observed data, thereby enabling the learner to generalize to unseen instances without prior domain-specific knowledge beyond the hypothesis representation.[3] A primary contribution of version space learning lies in its provision of an exact, complete representation of the set of all plausible hypotheses that align with the training examples, ensuring no potentially correct hypothesis is prematurely eliminated unless explicitly contradicted by new evidence. This conservative strategy prevents overgeneralization, a common pitfall in inductive methods, and supports reliable classification by unanimous agreement among the remaining hypotheses when applied to novel data. Furthermore, it facilitates practical advancements in learning systems, such as the ability to detect inconsistencies in the data or to select informative examples that maximally reduce hypothesis ambiguity.[1][3] The method's inductive bias is explicitly tied to the assumption that the target concept c is contained within the hypothesis space H, which serves as the searchable universe of possible concepts; this bias allows for deductive justification of predictions but contrasts with purely statistical approaches by guaranteeing exactness in noise-free environments where sufficient examples are provided. In the context of inductive learning as a whole—a process of deriving general rules from finite, specific observations—version space learning exemplifies a logically rigorous framework that leverages partial orderings over hypotheses to refine the solution space iteratively, laying groundwork for more scalable symbolic learning techniques.[4][3]Core Concepts

Hypothesis and Instance Spaces

In version space learning, the instance space refers to the complete set of all possible instances or examples that the learner might encounter, typically structured as attribute-value pairs describing observable properties of objects or events. For instance, in the EnjoySport domain, each instance is a conjunction of discrete attribute values, such as sky (sunny, cloudy, rainy), air temperature (warm, cold), humidity (normal, high), wind (strong, weak), water (warm, cool), and forecast (same, change), yielding a finite space of possible instances.[5][6] The hypothesis space encompasses all conceivable hypotheses that map instances from to classifications, usually {0,1} indicating negative or positive examples relative to an unknown target concept . Hypotheses in are commonly represented as conjunctions of constraints on the attributes, formalized as where each can be a specific value (e.g., sky = sunny), a wildcard "?" (indicating "don't care," matching any value), or (indicating impossibility, matching no value). This representation ensures is finite when is, and it must include the target concept . The space includes a maximally general hypothesis, often denoted as with all "?" wildcards, which classifies every instance as positive, and maximally specific hypotheses, such as those with in positions that make them inconsistent except for exact matches.[5][6] A key property of is its partial ordering by generality, where a hypothesis is more general than (denoted ) if, for every instance , whenever —meaning covers all positive instances covered by and possibly more. This ordering forms a lattice structure, with the maximally general hypothesis at the top and maximally specific ones at the bottom, enabling efficient search for consistent hypotheses during learning. The version space is the subset of consistent with observed training data, bounded by this partial order.[5][6] Hypotheses are often encoded as vectors mirroring the instance attributes, such as for a hypothesis that requires cold air temperature and high humidity but ignores other attributes. This vector form facilitates comparison under the generality ordering: if, for each attribute , the constraint in is at least as general as in (e.g., "?" is more general than a specific value, which is more general than ). Such properties ensure the hypothesis space supports monotonic generalization, where additional positive examples can only narrow the space without invalidating prior consistencies.[5][6]Version Space Boundaries

In version space learning, the version space represents the subset of hypotheses from the hypothesis space that are consistent with the observed training examples. Formally, , where is the set of training examples, each consisting of an instance and its classification (positive or negative). The hypotheses in are partially ordered by a generality relation, where a hypothesis is more general than (denoted ) if, for every instance , whenever —meaning covers all instances classified positively by and possibly more.[1] The specific boundary of the version space consists of the maximally specific hypotheses within , which minimally cover all positive training examples while excluding all negative ones. These hypotheses represent the most restrictive consistent rules, ensuring no unnecessary generalizations that might include negatives. Initially, is empty before any positive examples are observed, or set to the first positive example upon its arrival, forming a single maximally specific hypothesis that matches only that instance.[1] In contrast, the general boundary comprises the minimally general hypotheses in , which maximally cover positive examples without encompassing any negatives. These form the least restrictive consistent rules, often initialized as the set of all maximally general hypotheses in , such as the fully unconstrained hypothesis in conjunctive domains, which predicts positive for all instances until refined.[1] Under the assumption that the hypothesis space is closed under generalization and specialization—meaning for any two hypotheses, their least general generalization and most specific specialization also exist in —the boundaries and provide a complete and compact representation of the entire . Specifically, any hypothesis is more specific than or equal to at least one and more general than or equal to at least one , allowing efficient maintenance without enumerating all hypotheses in , which could be exponentially large. This boundary representation ensures that the version space can be queried or reduced scalably, supporting algorithms like candidate elimination for concept learning.[1]The Candidate Elimination Algorithm

Initialization and Example Processing

The Candidate Elimination algorithm begins with the initialization of two boundary sets that define the version space: the general boundary , which contains the maximally general hypotheses consistent with the training data, and the specific boundary , which contains the maximally specific hypotheses consistent with the data.[1] Initially, is set to the singleton set containing the single most general hypothesis in the hypothesis space , typically represented as for an attribute-value learning problem, where each "?" denotes an arbitrary value matcher that accepts any instance attribute.[3] The initial specific boundary is set to the empty set .[3] Upon encountering the first positive training example , the algorithm updates by setting it to the singleton set containing the description of itself, as this is the most specific hypothesis consistent with the positive classification.[1] Any hypotheses in inconsistent with this example—meaning they would incorrectly classify as negative—are removed.[3] This initialization ensures the version space starts bounded by the extremes of and immediately incorporates the first confirming evidence, setting the stage for incremental refinement.[1] The core of the algorithm is its incremental processing of subsequent training examples, which refines the version space without revisiting prior data. For each new example , where is the classification label (positive or negative), the algorithm first removes from and any hypotheses inconsistent with —that is, hypotheses that do not correctly classify according to .[3] If is positive, the boundary is then minimally generalized using minimal generalizations with respect to to restore consistency; similarly, if is negative, the boundary is minimally specialized using minimal specializations with respect to (with details of these operations covered in boundary update rules).[1] This process maintains the invariant that contains only maximally specific consistent hypotheses and contains only maximally general consistent ones, ensuring the version space captures all viable candidates, where denotes the subsumption partial order.[3] The overall procedure follows a straightforward loop over the training examples, as outlined in the high-level pseudocode below, assuming a noise-free dataset and that the target concept is representable in :Initialize G to {most general hypothesis in H}

Initialize S to ∅

Load training examples D

For each example d in D:

Remove from S any inconsistent with d

Remove from G any inconsistent with d

If d is positive:

If S is now empty (as for the first positive example):

Set S = {d}

Else:

Generalize S using minimal generalizations with respect to d, ensuring consistency with G

Else: // d is negative

Specialize G using minimal specializations with respect to d, ensuring consistency with S

If S is empty or G is empty:

Halt: Inconsistent training data (version space empty)

If the boundaries S and G have converged (e.g., |S| = |G| and S = G):

Halt: Version space converged to target concept

Output VS or report inconsistency

Initialize G to {most general hypothesis in H}

Initialize S to ∅

Load training examples D

For each example d in D:

Remove from S any inconsistent with d

Remove from G any inconsistent with d

If d is positive:

If S is now empty (as for the first positive example):

Set S = {d}

Else:

Generalize S using minimal generalizations with respect to d, ensuring consistency with G

Else: // d is negative

Specialize G using minimal specializations with respect to d, ensuring consistency with S

If S is empty or G is empty:

Halt: Inconsistent training data (version space empty)

If the boundaries S and G have converged (e.g., |S| = |G| and S = G):

Halt: Version space converged to target concept

Output VS or report inconsistency

Boundary Update Rules

In version space learning, the boundary update rules define how the specific boundary (maximally specific hypotheses) and general boundary (maximally general hypotheses) are adjusted to maintain consistency with new training examples, ensuring the version space contains only hypotheses that classify the examples correctly.[3][1] For a positive example (classified as belonging to the target concept), the update proceeds as follows: each hypothesis that does not classify as positive is replaced by its minimal generalization with respect to , denoted , which is the least general hypothesis subsuming both and ; hypotheses in that already classify as positive remain unchanged. Additionally, any that does not classify as positive is removed, as it is inconsistent with the example. If the new generalizations introduced to are not subsumed by existing members of , the boundary may be expanded with these minimal generalizations to preserve the maximally specific set.[3][1] The consistency of a hypothesis with an example is checked via the classification function: is positive if and only if , where attributes are indexed by and denotes a wildcard matching any value. The generalization operator computes the least general generalization (LGG) component-wise: if , otherwise .[3] For a negative example (not belonging to the target concept), the update removes from any that classifies as positive, as such hypotheses are inconsistent and cannot be specialized further without violating prior positive examples. For each that classifies as positive, it is replaced by a set of minimal specializations , which are the least specific hypotheses more specific than that exclude ; these are typically generated by varying one attribute differing from to a value that excludes it (e.g., using near-miss heuristics to restrict the attribute to not match ), while ensuring the specializations subsume at least one to avoid inconsistency.[3][1] Specialization can be formalized via set difference or attribute restriction: for instance, includes hypotheses where one attribute (where or ) is set to a value excluding , minimizing the increase in specificity. The overall version space maintenance follows the recursive formulation , where is the correct classification of the new example ; this is efficiently represented and updated using the and boundaries without enumerating all hypotheses in .[3]Illustrative Examples

Enjoy Sport Domain

The Enjoy Sport domain serves as a foundational example in concept learning, where the task is to determine whether a person enjoys their favorite water sport on a given day based on environmental conditions. The instance space consists of all possible days described by six discrete attributes: Sky (taking values sunny, cloudy, or rainy), AirTemp (warm or cold), Humidity (normal or high), Wind (strong or weak), Water (warm or cool), and Forecast (same or change). This results in a total of 96 possible instances, as the attributes have 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, and 2 values respectively.[3] Hypotheses in this domain are represented as conjunctions of constraints over these attributes, denoted as , where each is either a specific attribute value (e.g., sunny for Sky), "?" (matching any value for that attribute), or (matching no value, effectively excluding instances). Positive training examples are those days where the sport is enjoyed (labeled Yes), while negative examples are those where it is not (labeled No). For instance, the training instance sunny, warm, normal, strong, warm, same is positive, indicating enjoyment under these conditions, whereas rainy, cold, high, strong, warm, change is negative.[3] This domain illustrates the applicability of version space learning by providing a simple, relatable scenario for exploring conjunctive hypotheses and attribute-based constraints, where the goal is to identify conditions consistent with the observed training data without requiring complex computations.[3]Step-by-Step Boundary Evolution

The candidate elimination algorithm begins with the version space initialized by a single maximally general hypothesis in the general boundary set , represented as , where each "?" denotes any possible value for the corresponding attribute (Sky, AirTemp, Humidity, Wind, Water, Forecast).[3] The specific boundary set starts with a single maximally specific hypothesis, , indicating no constraints initially.[3] Processing the first positive training example—Sunny, Warm, Normal, Strong, Warm, Same—the algorithm replaces the initial specific hypothesis with this instance, yielding , as it is the only consistent specific hypothesis.[3] The general boundary remains unchanged, since the example is consistent with the maximally general hypothesis.[3] For the second positive example—Sunny, Warm, High, Strong, Warm, Same—the specific boundary generalizes by replacing the differing attribute (Humidity: Normal to High) with "?", resulting in .[3] Again, stays as , fully consistent with the example.[3] The third example, a negative instance—Rainy, Cold, High, Strong, Warm, Change—leaves unchanged, as it does not match the specific hypothesis and thus imposes no generalization.[3] However, specializes by eliminating the maximally general hypothesis and replacing it with minimally general ones that exclude this negative example, such as by restricting Sky to not Rainy, AirTemp to not Cold, and Forecast to not Change; this yields .[3] Finally, the fourth positive example—Sunny, Warm, High, Strong, Cool, Change—generalizes further by replacing Water (Warm to Cool) and Forecast (Same to Change) with "?", producing .[3] For , inconsistent hypotheses (e.g., the one restricting Forecast to Same) are removed, leaving .[3] These boundaries represent all hypotheses consistent with the full training dataset.[3] The evolution of the boundaries is illustrated in the following table, showing the state after each example and the key updates that eliminate inconsistent hypotheses:| After Example | Specific Boundary | General Boundary | Key Update |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initialization | N/A | ||

| 1 (Positive: Sunny, Warm, Normal, Strong, Warm, Same) | Replace initial with the example; no change to .[3] | ||

| 2 (Positive: Sunny, Warm, High, Strong, Warm, Same) | Generalize Humidity in to "?"; no change to .[3] | ||

| 3 (Negative: Rainy, Cold, High, Strong, Warm, Change) | No change to ; specialize by adding minimal restrictions to exclude the negative.[3] | ||

| 4 (Positive: Sunny, Warm, High, Strong, Cool, Change) | Generalize Water and Forecast in to "?"; remove inconsistent hypothesis from .[3] |