Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

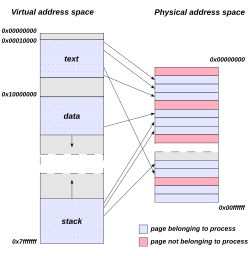

Virtual address space

View on WikipediaThis article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2012) |

In computing, a virtual address space (VAS) or address space is the set of ranges of virtual addresses that an operating system makes available to a process.[1] The range of virtual addresses usually starts at a low address and can extend to the highest address allowed by the computer's instruction set architecture and supported by the operating system's pointer size implementation, which can be 4 bytes for 32-bit or 8 bytes for 64-bit OS versions. This provides several benefits, one of which is security through process isolation assuming each process is given a separate address space.

Example

[edit]- In the following description, the terminology used will be particular to the Windows NT operating system, but the concepts are applicable to other virtual memory operating systems.

When a new application on a 32-bit OS is executed, the process has a 4 GiB VAS: each one of the memory addresses (from 0 to 232 − 1) in that space can have a single byte as a value. Initially, none of them have values ('-' represents no value). Using or setting values in such a VAS would cause a memory exception.

0 4 GiB VAS |----------------------------------------------|

Then the application's executable file is mapped into the VAS. Addresses in the process VAS are mapped to bytes in the exe file. The OS manages the mapping:

0 4 GiB VAS |---vvv----------------------------------------| mapping ||| file bytes app

The v's are values from bytes in the mapped file. Then, required DLL files are mapped (this includes custom libraries as well as system ones such as kernel32.dll and user32.dll):

0 4 GiB VAS |---vvv--------vvvvvv---vvvv-------------------| mapping ||| |||||| |||| file bytes app kernel user

The process then starts executing bytes in the EXE file. However, the only way the process can use or set '-' values in its VAS is to ask the OS to map them to bytes from a file. A common way to use VAS memory in this way is to map it to the page file. The page file is a single file, but multiple distinct sets of contiguous bytes can be mapped into a VAS:

0 4 GiB VAS |---vvv--------vvvvvv---vvvv----vv---v----vvv--| mapping ||| |||||| |||| || | ||| file bytes app kernel user system_page_file

And different parts of the page file can map into the VAS of different processes:

0 4 GiB VAS 1 |---vvvv-------vvvvvv---vvvv----vv---v----vvv--| mapping |||| |||||| |||| || | ||| file bytes app1 app2 kernel user system_page_file mapping |||| |||||| |||| || | VAS 2 |--------vvvv--vvvvvv---vvvv-------vv---v------|

On Microsoft Windows 32-bit, by default, only 2 GiB are made available to processes for their own use.[2] The other 2 GiB are used by the operating system. On later 32-bit editions of Microsoft Windows, it is possible to extend the user-mode virtual address space to 3 GiB while only 1 GiB is left for kernel-mode virtual address space by marking the programs as IMAGE_FILE_LARGE_ADDRESS_AWARE and enabling the /3GB switch in the boot.ini file.[3][4]

On Microsoft Windows 64-bit, in a process running an executable that was linked with /LARGEADDRESSAWARE:NO, the operating system artificially limits the user mode portion of the process's virtual address space to 2 GiB. This applies to both 32- and 64-bit executables.[5][6] Processes running executables that were linked with the /LARGEADDRESSAWARE:YES option, which is the default for 64-bit Visual Studio 2010 and later,[7] have access to more than 2 GiB of virtual address space: up to 4 GiB for 32-bit executables, up to 8 TiB for 64-bit executables in Windows through Windows 8, and up to 128 TiB for 64-bit executables in Windows 8.1 and later.[4][8]

Allocating memory via C's malloc establishes the page file as the backing store for any new virtual address space. However, a process can also explicitly map file bytes.

Linux

[edit]For x86 CPUs, Linux 32-bit allows splitting the user and kernel address ranges in different ways: 3G/1G user/kernel (default), 1G/3G user/kernel or 2G/2G user/kernel.[9]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "What is an address space?". IBM. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ "Virtual Address Space". MSDN. Microsoft.

- ^ "LOADED_IMAGE structure". MSDN. Microsoft.

- ^ a b "4-Gigabyte Tuning: BCDEdit and Boot.ini". MSDN. Microsoft.

- ^ "/LARGEADDRESSAWARE (Handle Large Addresses)". MSDN. Microsoft.

- ^ "Virtual Address Space". MSDN. Microsoft.

- ^ "/LARGEADDRESSAWARE (Handle Large Addresses)". MSDN. Microsoft.

- ^ "/LARGEADDRESSAWARE (Handle Large Addresses)". MSDN. Microsoft.

- ^ "Linux kernel - x86: Memory split".

References

[edit]- "Advanced Windows" by Jeffrey Richter, Microsoft Press

Virtual address space

View on Grokipedia- Text (code) segment: Contains the executable machine instructions of the program.

- Rodata (read-only data) segment: Holds read-only constants and string literals.

- Data segment: Stores initialized global and static variables.

- BSS segment: Reserves space for uninitialized global and static variables, initialized to zero by the system.

- Heap: Provides dynamic memory allocation, growing upwards from the end of the BSS segment.

- Stack: Manages local variables, function calls, and parameters, growing downwards from the high end of the address space; it often includes the argc (argument count), argv (argument vector) array, and environment variables at its top.[4]

Fundamentals

Definition and Purpose

The virtual address space is the set of memory addresses that a process uses to reference locations in memory, providing an isolated and abstract view of the system's memory for each running program.[5] It consists of a range of virtual addresses generated by the process, which are distinct from physical addresses in the actual hardware memory, and are mapped to physical memory locations by the operating system in conjunction with hardware mechanisms.[5] This abstraction ensures that each process operates within its own private memory environment, preventing direct access to the memory of other processes.[5] The primary purpose of the virtual address space is to enable concurrent execution of multiple processes on the same system without interference, facilitating multiprogramming and time-sharing environments.[5] It supports memory protection by isolating processes, thereby enhancing system security and stability, as one process cannot inadvertently or maliciously overwrite another's memory.[5] Additionally, it allows programs to utilize more memory than is physically available by incorporating swapping or paging techniques, where inactive portions of a process's memory are temporarily moved to secondary storage.[5] Key characteristics of a virtual address space include its provision of a contiguous logical view of memory to the process, despite the potentially fragmented nature of physical memory allocation.[5] The size is determined by the addressing architecture, typically 32 bits (yielding 4 GB) in older systems or 64 bits (up to 16 exabytes, though often limited in practice) in modern ones, allowing for vast addressable ranges.[6] It is commonly divided into distinct regions such as the text segment for executable code, data segment for initialized variables, heap for dynamic allocation, and stack for function calls and local variables.[5] Historically, the concept originated in the late 1950s to address memory fragmentation and protection challenges in early multiprogramming systems, with the first implementation in the Atlas computer at the University of Manchester in 1959.[7]Virtual Addresses vs. Physical Addresses

Virtual addresses are generated by the CPU during program execution and represent offsets within a process's virtual address space, providing an abstraction that does not directly correspond to specific hardware memory locations.[8] In contrast, physical addresses refer to the actual locations in physical memory, such as RAM, where data is stored and accessed by the hardware.[9] This distinction allows each process to operate under the illusion of having its own dedicated, contiguous memory space, independent of the underlying physical memory configuration.[10] The mapping from virtual to physical addresses occurs at runtime through hardware and software mechanisms, primarily handled by the memory management unit (MMU) in the CPU, which consults data structures maintained by the operating system to perform the translation.[11] For instance, the operating system decides which physical addresses correspond to each virtual address in a process, enabling dynamic allocation and protection without requiring programs to be aware of the physical layout.[12] As a result, a virtual address like 0x1000 accessed by a process might be translated to a physical address such as 0x5000, with no fixed binding between them, allowing the same program binary to run in different memory locations across executions or systems.[6] A typical virtual address space is divided into regions to enforce security and functionality, such as user space for application code and data (often in the lower addresses) and kernel space for operating system components (typically in the higher addresses, such as the upper 128 TB in x86-64 Linux systems).[13] These regions include attributes like read-only for code segments and writable for data areas, ensuring isolation where user-mode processes cannot access kernel areas directly, even though both may reside in the same virtual address space.[14] This layout supports relocation transparency, as virtual addresses remain consistent regardless of physical memory assignments, facilitating process loading at arbitrary locations without code modifications.[5]Address Translation Mechanisms

Paging

Paging divides the virtual address space of a process into fixed-size units known as pages, typically 4 KB in size, allowing the operating system to map these to corresponding fixed-size blocks in physical memory called page frames. This fixed-size allocation simplifies memory management by eliminating fragmentation issues associated with variable-sized blocks, enabling non-contiguous allocation of physical memory to virtual pages.[15][16] A virtual address in paging is composed of two parts: the virtual page number (VPN), which identifies the page within the virtual address space, and the offset, which specifies the byte position within that page. The number of bits allocated to the VPN and offset depends on the page size; for a 4 KB page (2^{12} bytes), the offset uses 12 bits, leaving the remaining bits for the VPN in systems with larger address spaces. The memory management unit (MMU) uses the VPN to index into a page table, a data structure that maps each VPN to a physical frame number (PFN) or indicates if the page is not present in memory.[16][15] In modern systems supporting 64-bit architectures like x86-64, which typically use 48-bit virtual addresses (sign-extended to 64 bits), single-level page tables become impractical due to their size—potentially requiring gigabytes of memory for sparse address spaces. Instead, hierarchical or multi-level page tables are employed, where the VPN is split across multiple levels (e.g., two or four levels, with 5-level paging introduced by Intel in 2017 and supported in hardware since 2019 for up to 57-bit virtual addresses), with each level indexing a smaller table that points to the next, ultimately leading to the leaf page table entry (PTE) containing the PFN. Each PTE also includes metadata such as presence bits, protection flags, and reference/modified bits for efficient management. The translation process involves walking these levels: the MMU shifts and masks the virtual address to extract indices for each level, fetching PTEs from physical memory or a translation lookaside buffer (TLB) cache if available.[17][18][19] If a page is not present in physical memory, accessing it triggers a page fault, an interrupt handled by the operating system kernel. The OS fault handler checks if the page is valid (e.g., mapped to disk) and, if so, allocates a free physical frame, loads the page from secondary storage (like disk or swap space), updates the PTE, and resumes the process; invalid accesses may result in segmentation faults or termination. This mechanism supports demand paging, where pages are loaded into memory only upon first access, reducing initial memory footprint and enabling larger virtual address spaces than physical memory availability.[20][21] The physical address is computed as the PFN from the PTE multiplied by the page size, plus the offset from the virtual address: \text{[Physical address](/page/Physical_address)} = (\text{PFN} \times \text{page size}) + \text{offset} This formula ensures byte-level alignment within the frame.[16] Paging variants enhance efficiency in specific scenarios. Demand paging, as noted, defers loading until needed, often combined with page replacement algorithms like least recently used (LRU) to evict frames when physical memory is full. Copy-on-write (COW) allows multiple processes to share the same physical pages initially (e.g., after a fork operation), marking them read-only in PTEs; upon a write attempt to a shared page, a page fault triggers the OS to copy the page into a new frame for the writing process, preserving isolation while minimizing initial duplication overhead.[22][23]Segmentation

Segmentation divides the virtual address space into variable-sized segments that correspond to logical units of a program, such as code, data, and stack sections. Unlike fixed-size paging, each segment can have a different length tailored to the needs of the program module, promoting modularity and easier sharing of code or data between processes. A virtual address in a segmented system consists of a segment selector, which identifies the segment, and an offset, which specifies the location within that segment. In modern 64-bit x86 systems, segmentation is simplified to a flat memory model, where most segment bases are zero and limits are ignored except for compatibility and specific uses like thread-local storage (FS/GS segments).[24] The operating system maintains a segment table, also known as a descriptor table, which stores entries for each segment. Each segment descriptor includes the base physical address where the segment resides in memory, the limit defining the segment's size, and access rights such as read-only for code segments or read-write for data segments. In architectures like the Intel x86, these descriptors are held in the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) or Local Descriptor Table (LDT), with the segment selector serving as an index into the appropriate table.[24] During address translation, the hardware uses the segment selector to retrieve the corresponding descriptor from the segment table. It then verifies that the offset does not exceed the segment's limit; if it does, a segmentation fault occurs. Upon successful validation, the base address from the descriptor is added to the offset to compute the physical address. This process enables direct mapping in pure segmentation or serves as an initial step before further translation in combined systems.[24] Pure segmentation maps segments directly to contiguous physical memory regions, which supports logical program structure but can suffer from external fragmentation as free memory holes form between allocated segments. To mitigate this, segmentation is frequently combined with paging, where each segment is subdivided into fixed-size pages that are mapped non-contiguously; this hybrid approach, as implemented in x86 segmented paging, eliminates external fragmentation while retaining the benefits of logical division.[25][26] Historically, segmentation gained prominence in the Multics operating system, developed in the 1960s, where it allowed for dynamic linking and sharing of procedures and data across processes in a time-sharing environment. This design influenced subsequent systems, including early Intel architectures like the 8086, which introduced segmentation to expand the addressable memory beyond the limitations of flat addressing.[27][24] In combined segmentation and paging schemes, internal fragmentation arises when a segment's size is not an exact multiple of the page size, leaving unused space in the final page of the segment. This inefficiency is typically limited to one page per segment but can accumulate in systems with many small segments.[26]Benefits and Limitations

Advantages

Virtual address spaces provide memory protection by isolating each process in its own independent address space, preventing unauthorized access to other processes' memory through hardware-enforced mechanisms such as access bits in page or segment tables that specify permissions like read, write, or execute.[16] This isolation enhances system security by ensuring that faults or malicious actions in one process do not corrupt others.[28] Efficient multitasking is enabled by virtual address spaces, which allow the operating system to overcommit physical memory by allocating more virtual memory to processes than is physically available, swapping infrequently used pages to disk as needed.[29] This approach supports running more processes simultaneously than the available RAM would otherwise permit, improving overall resource utilization without requiring all memory to be resident at once.[30] Virtual address spaces offer abstraction from physical memory constraints, presenting programs with a large, contiguous address space that hides the underlying hardware details and fragmentation issues.[6] This portability allows applications written for a standard virtual model to execute unchanged across diverse hardware platforms, as the operating system handles the mapping to physical resources.[31] Programming is simplified by virtual address spaces, as developers can allocate and use large, contiguous memory regions without managing physical layout, relocation, or fragmentation manually.[6] Linking and loading become straightforward since each program operates within a consistent virtual environment, reducing the complexity of memory management in application code.[32] Resource sharing is facilitated through mechanisms like shared memory mappings, where multiple processes can access the same physical pages via their virtual spaces, and copy-on-write techniques that initially share pages during process forking and duplicate them only upon modification.[30] This enables efficient inter-process communication and reduces memory duplication for common resources like libraries or data structures.[6]Challenges and Overhead

One significant challenge in virtual address space management is the translation overhead incurred during memory access. Each virtual address reference typically requires traversing the page table hierarchy via the memory management unit (MMU), which can involve multiple memory accesses and add substantial latency to every load or store operation.[15] In multi-level page tables, this process may demand up to four or more memory references per translation on a TLB miss, potentially leading to performance losses of up to 50% in data-intensive workloads.[33] Page tables themselves impose considerable memory overhead, consuming physical RAM to store mappings for the entire virtual address space. In 64-bit systems, multi-level page tables with four or five levels can require gigabytes of memory if fully populated, even though only a fraction of the address space is used, exacerbating resource contention in memory-constrained environments.[34] For instance, forward-mapped page tables for large virtual address spaces become impractical due to this exponential growth in storage needs.[15] Page fault handling introduces further performance degradation, as unmapped virtual addresses trigger interrupts that necessitate context switches and potentially disk I/O to load missing pages. This overhead can escalate dramatically under thrashing conditions, where excessive paging activity occurs due to overcommitted memory, leading to high page fault rates, prolonged wait times, and reduced CPU utilization as the system spends more time swapping pages than executing useful work.[35] Fragmentation remains an issue despite the contiguity provided in virtual address spaces. Paging eliminates external fragmentation in physical memory by allowing non-contiguous allocation of pages, but it introduces internal fragmentation, where allocated pages contain unused space because processes are rounded up to fixed page sizes, wasting memory within each frame.[36] Security vulnerabilities can arise from improper management of virtual address mappings, enabling exploits such as buffer overflows that corrupt adjacent memory regions within the process, potentially altering control flow or enabling arbitrary code execution.[37] Scalability challenges intensify with larger address spaces in 64-bit systems, where the complexity of managing multi-level page tables grows, increasing both translation latency and administrative overhead for operating systems handling terabyte-scale virtual memory.[33]Implementations in Operating Systems

Unix-like Systems

In Unix-like systems, each process operates within its own isolated, flat virtual address space, providing abstraction from physical memory constraints and enabling multitasking through kernel-managed paging. The kernel maintains per-process page tables to translate virtual addresses to physical ones, supporting demand paging where pages are allocated and loaded only upon access to optimize resource use. Mappings of files, devices, or anonymous regions into this space are handled via the POSIX-standard mmap() system call, which integrates seamlessly with the paging system for efficient I/O and sharing.[38] The typical layout of a process's virtual address space follows a conventional structure to facilitate binary loading and runtime growth. For executables in the ELF format, common on Unix-like systems, the loader maps the following segments into the virtual address space starting at low addresses, with the heap and stack positioned higher up:[39]- Text segment: Contains the executable code.

- Rodata segment: Contains read-only data, such as string constants.

- Data segment: Contains initialized data variables.

- BSS segment: Contains uninitialized data, which is allocated and zero-initialized at runtime.

- Heap: Used for dynamic allocations, begins after the BSS segment and expands upward via the brk() or sbrk() system calls, which adjust the break point—the end of the data segment.[40]

- Stack: For function calls and local variables, starts near the top of the user address space and grows downward, ensuring separation from the heap to prevent unintended overlaps. The initial stack layout includes argc at the base, followed by pointers to argv (the argument strings), environment pointers (envp), and an auxiliary vector.[41]