Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

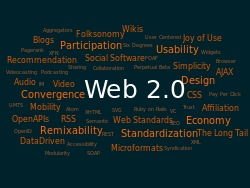

Tag cloud

View on Wikipedia

A tag cloud (also known as a word cloud or weighted list in visual design) is a visual representation of text data which is often used to depict keyword metadata on websites, or to visualize free form text. Tags are usually single words, and the importance of each tag is shown with font size or color.[2][3] When used as website navigation aids, the terms are hyperlinked to items associated with the tag.

History

[edit]

In the language of visual design, a tag cloud (or word cloud) is one kind of "weighted list", as commonly used on geographic maps to represent the relative size of cities in terms of relative typeface size. An early printed example of a weighted list of English keywords was the "subconscious files" in Douglas Coupland's Microserfs (1995). A German appearance occurred in 1992.[4]

The specific visual form and common use of the term "tag cloud" rose to prominence in the first decade of the 21st century as a widespread feature of early Web 2.0 websites and blogs, used primarily to visualize the frequency distribution of keyword metadata that describe website content, and as a navigation aid.

The first tag clouds on a high-profile website were on the photo sharing site Flickr, created by Flickr co-founder and interaction designer Stewart Butterfield in 2004. That implementation was based on Jim Flanagan's Search Referral Zeitgeist,[5] a visualization of Web site referrers. Tag clouds were also popularized around the same time by Del.icio.us and Technorati, among others.

Oversaturation of the tag cloud method and ambivalence about its utility as a web-navigation tool led to a decline of usage among these early adopters.[6] Flickr gave a five-word acceptance speech for the 2006 "Best Practices" Webby Award, which simply stated "sorry about the tag clouds."[7]

A second generation of software development discovered a wider diversity of uses for tag clouds as a basic visualization method for text data. Several extensions of tag clouds have been proposed in this context.

Types

[edit]

There are three main types of tag cloud applications in social software, distinguished by their meaning rather than appearance. In the first type, there is a tag for the frequency of each item, whereas in the second type, there are global tag clouds where the frequencies are aggregated over all items and users. In the third type, the cloud contains categories, with size indicating number of subcategories.

Frequency

[edit]In the first type, size represents the number of times that tag has been applied to a single item.[8] This is useful as a means of displaying metadata about an item that has been democratically "voted" on and where precise results are not desired.

In the second, more commonly used type,[citation needed] size represents the number of items to which a tag has been applied, as a presentation of each tag's popularity.

Significance

[edit]Instead of frequency, the size can be used to represent the significance of words and word co-occurrences, compared to a background corpus (for example, compared to all the text in Wikipedia).[9] This approach cannot be used standalone, but it relies on comparing the document frequencies to expected distributions.

Categorization

[edit]In the third type, tags are used as a categorization method for content items. Tags are represented in a cloud where larger tags represent the quantity of content items in that category.

There are some approaches to construct tag clusters instead of tag clouds, e.g., by applying tag co-occurrences in documents.[10]

More generally, the same visual technique can be used to display non-tag data,[11] as in a word cloud or a data cloud.

The term keyword cloud is sometimes used as a search engine marketing (SEM) term that refers to a group of keywords that are relevant to a specific website. In recent years tag clouds have gained popularity because of their role in search engine optimization of Web pages as well as supporting the user in navigating the content in an information system efficiently.[12] Tag clouds as a navigational tool make the resources of a website more connected,[13] when crawled by a search engine spider, which may improve the site's search engine rank. From a user interface perspective they are often used to summarize search results to support the user in finding content in a particular information system more quickly.[14]

Visual appearance

[edit]Tag clouds are typically represented using inline HTML elements. The tags can appear in alphabetical order, in a random order, they can be sorted by weight, and so on. Sometimes, further visual properties are manipulated in addition to font size, such as the font color, intensity, or weight.[15] Most popular is a rectangular tag arrangement with alphabetical sorting in a sequential line-by-line layout. The decision for an optimal layout should be driven by the expected user goals.[15] Some prefer to cluster the tags semantically so that similar tags will appear near each other[16][17][18] or use embedding techniques such as tSNE to position words.[9] Edges can be added to emphasize the co-occurrences of tags and visualize interactions.[9] Heuristics can be used to reduce the size of the tag cloud whether or not the purpose is to cluster the tags.[17]

Tag cloud visual taxonomy is determined by a number of attributes: tag ordering rule (e.g. alphabetically, by importance, by context, randomly, ordered for visual quality), shape of the entire cloud (e.g. rectangular, circle, given map borders), shape of tag bounds (rectangle, or character body), tag rotation (none, free, limited), vertical tag alignment (sticking to typographical baselines, free). A tag cloud on the web must address problems of modeling and controlling aesthetics, constructing a two-dimensional layout of tags, and all these must be done in short time on volatile browser platform. Tags clouds to be used on the web must be in HTML, not graphics, to make them robot-readable, they must be constructed on the client side using the fonts available in the browser, and they must fit in a rectangular box.[19]

Data clouds

[edit]

A data cloud or cloud data is a data display which uses font size and/or color to indicate numerical values.[20] It is similar to a tag cloud[21] but instead of word count, displays data such as population or stock market prices.

Text clouds

[edit]

A text cloud or word cloud is a visualization of word frequency in a given text as a weighted list.[23] The technique has recently[when?] been popularly used to visualize the topical content of political speeches.[22][24]

Collocate clouds

[edit]Extending the principles of a text cloud, a collocate cloud provides a more focused view of a document or corpus. Instead of summarising an entire document, the collocate cloud examines the usage of a particular word. The resulting cloud contains the words which are often used in conjunction with the search word. These collocates are formatted to show frequency (as size) as well as collocational strength (as brightness). This provides interactive ways to browse and explore language.[25]

Perception

[edit]Tag clouds have been the subjects of investigation in several usability studies. The following summary is based on an overview of research results given by Lohmann et al.:[15]

- Tag size: Large tags attract more user attention than small tags (effect influenced by further properties, e.g., number of characters, position, neighboring tags).

- Scanning: Users scan rather than read tag clouds.

- Centering: Tags in the middle of the cloud attract more user attention than tags near the borders (effect influenced by layout).

- Position: The upper left quadrant receives more user attention than the others (Western reading habits).

- Exploration: Tag clouds provide suboptimal support when searching for specific tags (if these do not have a very large font size).

Felix et al.[26] compared how human reading performance differs from traditional tag clouds that map numeric values to the size of the font and alternative designs that uses for example color or additional shapes like circle and bars. They also compared how different arrangement of the words affects performance.

- Use of an additional bar or circle instead of the font size increases accuracy when reading the numeric value

- However, users could find specific word quicker when no additional mark is used

- The performance depends on the task, simple tasks like finding a word are highly affected by the design choice, however the effect on tasks like identifying the topic of a tag cloud is much smaller.

Creation

[edit]

In principle, the font size of a tag in a tag cloud is determined by its incidence. For a word cloud of categories like weblogs, frequency, for example, corresponds to the number of weblog entries that are assigned to a category. For smaller frequencies one can specify font sizes directly, from one to whatever the maximum font size. For larger values, a scaling should be made. In a linear normalization, the weight of a descriptor is mapped to a size scale of 1 through f, where and are specifying the range of available weights.

- for ; else

- : display fontsize

- : max. fontsize

- : count

- : min. count

- : max. count

Since the number of indexed items per descriptor is usually distributed according to a power law,[28] for larger ranges of values, a logarithmic representation makes sense.[29]

Implementations of tag clouds also include text parsing and filtering out unhelpful tags such as common words, numbers, and punctuation.

There are also websites creating artificially or randomly weighted tag clouds, for advertising, or for humorous results.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Word-Cloud Generator (archive)

- ^ Martin Halvey and Mark T. Keane, An Assessment of Tag Presentation Techniques Archived 2017-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, poster presentation at WWW 2007, 2007

- ^ Helic, Denis; Trattner, Christoph; Strohmaier, Markus; Andrews, Keith (2011). "Are tag clouds useful for navigation? A network-theoretic analysis". International Journal of Social Computing and Cyber-Physical Systems. 1 (1): 33. doi:10.1504/IJSCCPS.2011.043603. ISSN 2040-0721.

- ^ Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari (1992). Tausend Plateaus. Kapitalismus und Schizophrenie. Merve-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-88396-094-4.

- ^ A copy of Jim Flanagan's Search Referral Zeitgeist was available at archive.org but has since been blocked. In the comments of a blog entry Archived 2006-04-26 at the Wayback Machine, a user identified as Steve Minutillo attribute the idea to Jim Flanagan, stating that Flanagan's site had such displays in 2002.

- ^ "Tag Clouds R.I.P.?". Readwriteweb.com. 2011-03-30. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19.

- ^ "Welcome to the Webby Awards". Webbyawards.com. 2011-10-28. Archived from the original on 2006-07-03. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ^ Bielenberg, K. and Zacher, M., Groups in Social Software: Utilizing Tagging to Integrate Individual Contexts for Social Navigation Archived 2007-10-08 at the Wayback Machine, Masters Thesis submitted to the Program of Digital Media, Universität Bremen (2006)

- ^ a b c Schubert, Erich; Spitz, Andreas; Weiler, Michael; Geiß, Johanna; Gertz, Michael (2017-08-11). "Semantic Word Clouds with Background Corpus Normalization and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding". arXiv:1708.03569 [cs.IR].

- ^ Knautz, K., Soubusta, S., & Stock, W.G. (2010). Tag clusters as information retrieval interfaces Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS-43), January 5–8, 2010. IEEE Computer Society Press (10 pages).

- ^ Aouiche, Kamel; Lemire, Daniel; Godin, Robert (2007). "Collaborative OLAP with Tag Clouds: Web 2.0 OLAP Formalism and Experimental Evaluation". arXiv:0710.2156 [cs.DB].

- ^ Helic, D.; Trattner, C.; Strohmaier, M.; Andrews, K. (2011). "Are Tag Clouds Useful for Navigation? A Network-Theoretic Analysis". International Journal of Social Computing and Cyber-Physical Systems. 1 (1): 33–55. doi:10.1504/IJSCCPS.2011.043603.

- ^ Trattner, C.:Linking Related Content in Web Encyclopedias with search query tag clouds Archived 2012-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. IADIS International Journal on WWW/Internet, Volume 9, Issue 2, 2011

- ^ Tratter, C., Lin, Y., Parra, D., Yue, Z., Brusilovsky, P.: Evaluating Tag-Based Information Access in Image Collections Archived 2012-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media (HT 2012). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2012

- ^ a b c Lohmann, S., Ziegler, J., Tetzlaff, L. Comparison of Tag Cloud Layouts: Task-Related Performance and Visual Exploration Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, T. Gross et al. (Eds.): INTERACT 2009, Part I, LNCS 5726, pp. 392–404, 2009.

- ^ Hassan-Montero, Y., Herrero-Solana, V. Improving Tag-Clouds as Visual Information Retrieval Interfaces Archived 2006-08-13 at the Wayback Machine. InSciT 2006: Mérida, Spain. October 25–28, 2006.

- ^ a b Kaser, Owen; Lemire, Daniel (2007). "Tag-Cloud Drawing: Algorithms for Cloud Visualization". arXiv:cs/0703109.

- ^ Salonen, J. 2007. Self-organising map based tag clouds – Creating spatially meaningful representations of tagging data Archived 2008-12-24 at the Wayback Machine. Proceedings of the 1st OPAALS conference, 26–27 November 2007, Rome, Italy.

- ^ Marszałkowski, J., Mokwa, D., Drozdowski, M., Rusiecki, L., Narożny, H. Fast algorithms for online construction of web tag clouds, Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 64, pp. 378–390, 2017.

- ^ Apel, Warren. "ManyEyes Visualization and Commentary: World Population Data Cloud.". Archived from the original on 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ^ Wattenberg, Martin. "ManyEyes Visualization: Ad cloud". Archived from the original on 2008-02-14. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ a b Steinbock, Daniel (5 March 2011). "TagCrowd visualization: State of the Union". Archived from the original on 2011-04-11. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ^ Lamantia, Joe. "Text Clouds: A New Form of Tag Cloud?". Archived from the original on 2008-09-10. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Mehta, Chirag. "US Presidential Speeches Tag Cloud". Archived from the original on 2007-10-19. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ "Collocate cloud". Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ Felix, Cristian; Franconeri, Steven; Bertini, Enrico (Jan 2018). "Taking Word Clouds Apart: An Empirical Investigation of the Design Space for Keyword Summaries". IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics. 24 (1): 657–666. Bibcode:2018ITVCG..24..657F. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2017.2746018. PMID 28866593. S2CID 6570943.

- ^ "Monthly wiki page Hits for en.wikipedia". Wikistics.falsikon.de. 2009-08-31. Archived from the original on 2013-04-19. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- ^ Voss, Jakob (2006). "Collaborative thesaurus tagging the Wikipedia way". arXiv:cs/0604036.

- ^ "Kentbyte: Tag Cloud Font Distribution Algorithm. June 2005". Echochamberproject.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

External links

[edit]- Understanding Tag Clouds – an information design analysis of tag clouds

- Design tips for building tag clouds – software development guide from O'Reilly's ONLamp

Tag cloud

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A tag cloud is a visualization method that summarizes a set of tags—user-generated keywords or phrases related to a resource or collection of resources—in a visually appealing manner, where visual attributes such as font size, color, or position encode the frequency, importance, or other metrics of the tags.[6] While tag clouds traditionally aggregate human-curated tags from collaborative systems like folksonomies, the terms "tag cloud" and "word cloud" are often used interchangeably; word clouds may derive terms from text frequencies in documents or corpora, emphasizing frequency-based representations over strict human metadata.[6][1] Tag clouds serve to aid information seeking and navigation by providing an at-a-glance summary of content themes, often depicting metadata on websites or visualizing free-form text in social tagging environments known as folksonomies, where users collectively classify resources through shared tags.[6][8] Common applications include summarizing search results, enhancing site navigation on platforms like blogs or social media, and highlighting popular topics in user-generated content ecosystems.[6] Key components of a tag cloud include the tags themselves (words or short phrases), weighting mechanisms such as font size scaled proportionally to tag occurrence or relevance, and often hyperlinks attached to each tag for direct access to related resources.[6] These elements combine to create an intuitive, scannable interface that prioritizes prominent tags while maintaining overall readability.[6]History

The origins of tag clouds predate their widespread digital use, with early conceptual precursors in psychological and artistic contexts. In 1976, psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment asking participants to name landmarks in Paris, visualizing the results as a collective "mental map" where font sizes reflected mention frequency, one of the first uses of variable text sizing for data representation.[4] Another early example appeared in 1992 on the cover of the German edition of Mille Plateaux by philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, featuring a weighted word placement summarizing key concepts.[5] These ideas built on early text visualization techniques in the 1990s, laying groundwork for weighted textual displays.[4] Tag clouds gained practical form in the early 2000s through web implementations on platforms like del.icio.us, launched in late 2003, which used tag lists to organize user bookmarks, and Flickr, introduced in 2004, which visualized photo tags with varying font sizes to indicate popularity.[4][9] The term "tag cloud" emerged in the mid-2000s alongside the rise of folksonomies—user-driven tagging systems coined by information architect Thomas van der Wal in 2004.[10] Initial implementations emphasized static visualizations of tag frequencies, but developers advanced to dynamic, interactive versions allowing users to click tags for navigation. By the late 2000s, tag clouds reached peak popularity in blogging and social media, integrated into content management systems like WordPress via plugins such as Ultimate Tag Warrior, which received significant updates in 2006 to support tag cloud generation.[11] Academic interest in tag cloud layouts began in 2006, with early papers exploring optimization algorithms and user interaction, such as those presented at conferences like CHI.[12] Usage declined post-2010 as advanced search tools and algorithmic recommendations on platforms like Google and social networks reduced reliance on manual tag navigation, leading to oversaturation concerns. However, tag clouds experienced a resurgence in the 2020s within data analytics software, evolving into word clouds for summarizing qualitative data in tools like Many Eyes and modern BI platforms, emphasizing their role in quick textual overviews.[13][14]Types and Variants

Frequency-based

In frequency-based tag clouds, the prominence of each tag—typically represented by font size—is determined solely by its raw occurrence count within a dataset, such as user-assigned labels in a folksonomy or keywords extracted from a text corpus.[15] This approach treats frequency as the primary metric of relevance, with more frequently occurring tags rendered in larger fonts to visually emphasize dominant themes or topics. The rationale for frequency-based sizing lies in its simplicity as a method to summarize large collections of textual data, enabling users to quickly grasp prevalent patterns without delving into detailed analysis. By scaling visual attributes proportionally to counts, these tag clouds facilitate intuitive navigation and overview tasks, particularly in environments like social bookmarking sites where common tags signal popular content.[15] For instance, early implementations on platforms such as Flickr and Delicious displayed user tags for photos or links, with sizes reflecting how often tags like "nature" or "programming" appeared across contributions, helping users browse related items efficiently.[15] Similarly, in news article analysis, frequency-based tag clouds from outlets like Technorati highlighted recurring topics such as "election" or "economy" based on article keyword counts, providing a snapshot of coverage trends. Computing tag sizes in this model is straightforward and resource-efficient, often involving linear normalization of frequencies to map them onto a predefined range of font sizes. A common formula for assigning an importance level (typically from 0 to 9, which then corresponds to discrete font sizes like 8pt to 44pt) is: where is the frequency of the current tag, is the maximum frequency in the dataset, and is the minimum frequency among retained tags.[16] This yields an intuitive visualization where higher-frequency tags dominate spatially, making it ideal for rapid thematic overviews in applications like blog aggregators or document corpora such as Project Gutenberg texts. Despite these advantages, frequency-based tag clouds have limitations, as they overlook semantic context or tag relationships, potentially amplifying noise from overly common but uninformative terms—such as stop words like "the" in raw text extractions—without additional preprocessing. In contrast to weighted variants that incorporate external significance measures, this pure count-driven method prioritizes sheer prevalence over nuanced importance.Weighted and Significance-based

In weighted and significance-based tag clouds, tags are sized or positioned according to metrics that incorporate contextual importance or relevance beyond mere occurrence counts, such as term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) or user-assigned significance scores.[17][18] This approach builds on basic frequency weighting by emphasizing tags that provide greater discriminatory value within a collection.[19] The rationale for significance-based weighting stems from the limitations of pure frequency measures, which often amplify common but less informative tags while underrepresenting rare yet semantically critical ones.[17] By assigning higher visual prominence to tags with elevated specificity or perceived relevance, these clouds better facilitate semantic insight and user navigation, as demonstrated in studies showing improved item selection efficiency compared to flat lists.[17] For instance, in social tagging systems, users can manually assign weights reflecting importance and confidence, enabling collective prioritization of meaningful descriptors over rote popularity.[18] Computation typically involves established formulas like TF-IDF, which quantifies a term's importance in a document relative to an entire corpus. The standard TF-IDF score for a term in document is given by: where is the frequency of in , is the number of documents containing , and is the total number of documents.[19][17] These scores are then normalized and mapped to visual attributes, such as font sizes in discrete classes, to render the cloud. User-assigned significance, by contrast, relies on direct input, such as scales from 1 to 100 per tag, aggregated across contributors for composite weights.[18] Examples include search engine result summaries, where TF-IDF-weighted tag clouds visualize key terms from retrieved web documents, aiding quick relevance judgments in explorative browsing of topics like economics or technology news.[17] In social media and collaborative tagging platforms like Delicious or Flickr, trends are depicted with tags weighted by engagement metrics or user-assigned importance, highlighting influential descriptors such as "assessment" in educational content based on collective confidence scores.[18] Advantages of this approach include enhanced semantic representation and reduced overlap in tag meanings, leading to more diverse and discriminative visualizations that cover broader collection aspects with lower redundancy (e.g., 0.024 average overlap versus 0.050 in frequency-based methods).[20] However, it demands additional computational overhead for corpus analysis or user input aggregation, potentially complicating real-time generation and introducing biases from limited participant expertise.[17][18]Specialized Variants

Data clouds adapt the tag cloud format to visualize numerical datasets, where tags represent categories and their visual prominence—such as font size—is determined by aggregated values like sums, averages, or counts within those categories. For instance, in business intelligence applications, product categories can be displayed with sizes proportional to total sales figures, enabling quick identification of high-performing items without relying on textual frequency alone. This variant shifts focus from linguistic content to quantitative metrics, often integrated into dashboard tools for exploratory data analysis.[21] Text clouds, a variant emphasizing natural language processing techniques, generate visualizations from processed textual corpora by extracting key terms while excluding common stop words such as "the" or "and" to highlight meaningful content. These clouds are particularly applied in sentiment analysis, where word sizes reflect the intensity or frequency of emotionally charged terms, aiding in the rapid assessment of opinions within reviews, social media posts, or survey responses. For example, a text cloud derived from customer feedback might enlarge words like "excellent" or "disappointing" based on their contextual weight after preprocessing with tokenization and lemmatization. This approach leverages NLP pipelines to filter noise and prioritize substantive vocabulary, enhancing interpretability in qualitative data exploration. Collocate clouds extend tag cloud principles to illustrate word co-occurrences within a corpus, arranging terms based on their proximity or association strength to a central keyword, with visual attributes like size or position encoding the degree of collocation. In this setup, tags are positioned to reflect spatial or semantic closeness in the source text—for example, words frequently adjacent to "climate" in environmental reports might cluster nearby, sized by mutual information scores measuring co-occurrence likelihood beyond chance. This variant facilitates targeted linguistic analysis, such as identifying thematic patterns in large document collections, by transforming statistical associations into an intuitive spatial layout.[22] Among other specialized variants, hierarchical tag clouds organize nested relationships among tags using multi-level layouts, such as spherical arrangements where inner spheres represent parent categories and outer ones depict sub-tags, with colors or opacities distinguishing levels to preserve relational depth. TagSpheres, introduced in 2016, exemplify this by positioning co-occurring terms relative to a query keyword in a 3D-like spherical projection, allowing users to navigate tag hierarchies in textual summaries like news archives or ontologies. Complementing this, dynamic or animated tag clouds incorporate temporal elements to depict evolving trends, integrating miniature line charts (sparklines) alongside tags to show frequency changes over time without separate panels. SparkClouds, developed in 2010, embed these sparklines within traditional tag layouts to compare multiple time-series clouds, such as tracking topic popularity in blog streams, thereby revealing patterns like rising or declining interests.[23][3] Geospatial tag clouds map location-based tags onto geographic projections, scaling and positioning elements according to spatial density or relevance to coordinates, as explored in recent studies on points-of-interest visualization. For example, a 2023 analysis proposed location-based services (LBS) tag clouds that center tags around a user's position, prioritizing nearby attractions or events by aggregating geo-referenced data from social platforms, with layout algorithms optimizing overlap in cartographic displays. This variant supports context-aware navigation, such as urban exploration apps, by blending tag prominence with map projections to highlight regionally significant terms.[24]Design and Visualization

Layout and Appearance

Tag clouds arrange tags in a two-dimensional or three-dimensional space to convey relative importance through visual properties, primarily varying font sizes while positioning elements to avoid overlaps and maximize space efficiency. Early implementations, popularized by platforms like Flickr in 2004, employed simple horizontal layouts where tags were placed left-to-right and top-to-bottom in alphabetical order, mimicking paragraph-style text for straightforward readability.[25][26] Common layout algorithms include horizontal packing variants, spiral arrangements, and force-directed models. Horizontal methods, such as greedy shelf-packing heuristics like First-Fit Decreasing Height (FFDH), sort tags by size and place them on shelves (rows) to minimize height and reduce wasted space, achieving up to 3% improvement in compactness over basic greedy approaches.[27] Spiral layouts, often using Archimedean spirals, position tags in a circular or spherical pattern starting from a central point, which is particularly effective for hierarchical data by placing related tags along expanding coils to maintain proximity.[5] Force-directed algorithms simulate physical forces, where larger tags exert greater repulsion to prevent overlaps, treating tags as nodes in a graph and iteratively adjusting positions for balanced distribution and aesthetic appeal.[28] Appearance in tag clouds emphasizes font size variation to reflect tag frequency or significance, with larger sizes for more prominent tags, alongside optional color coding to denote categories or hierarchies—such as a red-to-blue gradient for levels in spherical layouts.[27][5] Rotations, typically limited to 0° or small angles to preserve readability, can add aesthetic dynamism without compromising legibility. Modern extensions incorporate 3D projections, like TagSpheres, which embed tags on concentric spheres to visualize hierarchical relations, using polar coordinates for placement and minimal padding to handle overlaps while ensuring no occlusion of text.[5] Key challenges in layout include preventing tag overlaps, which algorithms address through bounding box checks and spacing (e.g., 2-pixel margins), and optimizing readability amid varying sizes, often by avoiding extreme rotations or excessive white space that can lead to cluttered visuals.[27] The weighted force model exemplifies this by scaling repulsion inversely with tag size, promoting even distribution in dense clouds. Historical standards evolved from basic inline HTML placements to these optimized techniques, with 3D variants emerging around 2009 to enhance depth perception in complex datasets.[28] Poorly executed layouts risk visual clutter, underscoring the need for algorithms that balance density and clarity.[27]Styling Elements

Typography in tag clouds plays a crucial role in enhancing readability and visual hierarchy, with sans-serif font families often preferred for their clarity and reduced perceptual biases associated with variable letter widths. For instance, studies have shown that sans-serif fonts can help mitigate length-based biases in font size encoding, where longer words may appear larger than intended. Boldness is commonly used for emphasis on higher-weight tags, as variations in font weight alongside size provide stronger perceptual cues than color intensity alone, leading to better user comprehension of frequency differences. Kerning adjustments, though less studied, can further refine spacing to prevent overcrowding and maintain aesthetic balance in dense layouts. Color schemes in tag clouds extend beyond monochrome variations to incorporate gradients and thematic palettes that encode additional attributes like frequency or semantic categories, thereby increasing informational density without sacrificing appeal. Gradients based on tag weight, such as light blue fades for temporal trends, help visualize changes over time while maintaining readability through white outlines and high-contrast elements. Thematic palettes, like assigning blue hues to frequency-based tags or red to significance indicators, can aid topic recognition, particularly when colors are semantically grouped rather than randomly applied. These approaches draw from established visualization principles, ensuring colors enhance rather than obscure the primary size-based encoding. Interactivity elements, such as hover effects and animations, add dynamism to tag clouds, allowing users to explore details on demand while adhering to accessibility standards. Hover effects that highlight tags—e.g., enlarging or changing color on mouse-over—facilitate quick identification of trends, as seen in implementations where tooltips reveal frequency data or sparklines. For dynamic clouds, subtle animations like fading in grouped tags improve engagement, but must include keyboard-navigable alternatives to comply with WCAG guidelines, ensuring content triggered by hover or focus is dismissible and hoverable without trapping the pointer. Accessibility considerations emphasize high-contrast ratios (at least 4.5:1 for text) to support users with low vision, alongside sufficient spacing to avoid unintended activations on touch devices. Best practices for tag cloud styling recommend limiting the number of tags to prevent visual clutter and maintain focus on prominent items, with optional filtering for lesser ones. Responsive design is essential for mobile compatibility, employing compact layouts that adapt to varying screen sizes without losing readability, such as horizontal alignments and scalable font ranges from 10 to 34 points. These guidelines prioritize perceptual accuracy and user efficiency, avoiding excessive elements that could dilute the cloud's overview purpose. Examples of tag cloud styling illustrate evolving trends from colorful early web implementations to minimalist approaches in modern dashboards. Early 2000s web designs often featured vibrant, multi-colored tags to denote weight alongside size, creating engaging but sometimes overwhelming visuals on sites like Flickr. In contrast, contemporary dashboards favor minimalist styles with neutral palettes, subtle gradients, and single-font variations for clean integration into data-heavy interfaces, as evaluated in semantic grouping studies.Generation Methods

Algorithms and Processes

The generation of tag clouds involves a structured computational pipeline that transforms raw textual data into a visual representation, emphasizing the relative importance of tags through size, position, and arrangement. This process typically begins with the collection and extraction of tags from source documents, followed by weighting to quantify significance, ranking and filtering to select relevant terms, layout application to position elements without overlap, and final rendering for display. These steps ensure that the resulting cloud conveys key themes efficiently while maintaining readability.[16] Tag collection starts with gathering raw data from sources such as documents, web pages, or user annotations, often involving natural language processing (NLP) techniques for extraction. Core algorithms for tag extraction preprocess text through tokenization to break it into words or phrases, followed by stemming—which reduces words to their root form by removing suffixes (e.g., "running" to "run")—and lemmatization, which maps words to their dictionary base form considering context and part-of-speech (e.g., "better" to "good"). These methods normalize variations like plurals or tenses, reducing redundancy and improving tag coherence; for instance, stemming uses rule-based heuristics like Porter's algorithm, while lemmatization relies on lexical resources such as WordNet. In folksonomy-based extraction, terms are further boosted by their co-occurrence in tagged datasets, using statistical scores like TF-IDF multiplied by smoothed tag probabilities to prioritize domain-relevant candidates. Heuristic filtering removes stop words (e.g., "the," "and") and low-frequency terms during this phase to focus on meaningful tags.[29][30] Weights are computed to reflect tag importance, commonly using term frequency (TF), which counts occurrences within a document, or the more sophisticated TF-IDF measure that accounts for rarity across a corpus. The TF-IDF score for a tag is calculated as , where is the frequency of in the document, is the total number of documents, and is the number of documents containing ; this downweights common terms like "internet" while elevating distinctive ones. Frequency-based weighting simply uses raw counts, suitable for user-generated tags, but TF-IDF enhances discrimination in large corpora. These weights are then normalized to map to visual attributes like font size, using the linear formula , where is the raw weight, and are the minimum and maximum weights, and and are user-specified font sizes (e.g., 10pt to 24pt). This ensures proportional scaling without extremes that impair legibility.[31][31] Following weighting, tags are ranked by their scores (descending order for prominence) and filtered to a manageable set, often selecting the top terms (e.g., ) based on thresholds like minimum frequency or relevance scores to avoid clutter. This step may incorporate clustering to group similar tags, reducing overlap and improving coverage; for example, hierarchical clustering merges synonymous terms (e.g., "car" and "automobile") using cosine similarity on TF-IDF vectors, allowing representative selection from clusters.[32][32] Layout algorithms then position the ranked tags in a bounded area, treating it as a 2D packing problem to minimize overlaps and optimize aesthetics like balance and whitespace. A common core algorithm is greedy placement, which iteratively adds tags in weight order, positioning each at the first available non-overlapping spot (e.g., scanning rows left-to-right, top-to-bottom) with an time complexity for tags; variants like First-Fit Decreasing Height (FFDH) sort tags by height (font size) descending and fit them into the lowest feasible row, reducing vertical span by up to 20% compared to naive greedy methods. For more balanced arrangements, min-cut heuristics recursively partition tags into subsets using graph bipartitioning, minimizing edge cuts to cluster related terms spatially. These heuristics prioritize readability by enforcing minimum spacing (e.g., 1-2 pixels between tags).[16][16] For large datasets exceeding thousands of tags, computation is optimized through sampling—randomly selecting a subset (e.g., 10-20% of tags) while preserving distribution via stratified methods—or clustering to aggregate similar items pre-layout, reducing the input size by 50-80% without significant information loss. Online algorithms like tabu search further enable real-time construction in browser environments by approximating optimal packing under resource constraints.[33][32] The final output is rendered as a static image (e.g., PNG via canvas drawing) or interactive format like HTML/SVG, where tags are styled spans or elements with applied font sizes and positions; SVG supports scalability and hover interactions, while HTML enables dynamic updates. This pipeline, when implemented efficiently, generates clouds in under a second for typical datasets of 100 tags.[16][33]Tools and Implementations

Various software tools and libraries facilitate the creation and deployment of tag clouds, ranging from client-side JavaScript implementations to server-side programming language packages.[34][35] In web development, JavaScript libraries such as d3-cloud, a module for the D3.js visualization library, enable the generation of customizable word clouds using HTML5 canvas for efficient layout computation.[34] Similarly, wordcloud2.js provides a lightweight option for rendering tag clouds on 2D canvas or HTML elements, supporting interactive features like shape masking.[36] Online generators like WordArt.com offer user-friendly, AI-powered interfaces for creating stylized word clouds without coding, allowing exports in various formats.[37] For programmatic generation, the Python wordcloud library, originally introduced in a 2012 blog post and first released on PyPI in 2015 with ongoing updates through 2024, supports advanced features like custom masking and color schemes for data visualization tasks.[38] In R, the wordcloud package, available on CRAN since 2011 and updated to version 2.6 in 2025, integrates with statistical workflows to produce word clouds from text corpora, emphasizing frequency-based visualizations. Content management system integrations simplify tag cloud deployment in popular platforms. WordPress users can employ plugins like Configurable Tag Cloud (CTC) Widget, last updated in March 2023, which allows extensive customization of tag displays including size, color, and ordering based on post counts. For MediaWiki, the WikiCategoryTagCloud extension, updated in September 2017, enables the embedding of category-based tag clouds on wiki pages using simple parser functions.[39] Modern web frameworks support interactive tag clouds through dedicated components. In React, libraries such as react-tagcloud leverage d3-cloud for dynamic, responsive word clouds that respond to user interactions like hovering or clicking.[40] Vue.js offers similar capabilities via VueWordCloud, a component that generates animated clouds from word-frequency data.[41] API services like Google Cloud Natural Language API assist in auto-tagging by extracting entities from text, providing input for cloud generation in these frameworks. Deployment options for tag clouds include embedding SVG or canvas elements directly into websites for interactivity, as seen with D3.js-based implementations, or exporting static images and PDFs using libraries like Python's wordcloud with Pillow integration. Most tools discussed are open-source under licenses like MIT, contrasting with proprietary online generators such as WordArt.com, which may impose usage limits on free tiers.[37]Evaluation and Applications

User Perception

Research from the late 2000s, including experiments conducted between 2007 and 2010, has examined how users interpret tag clouds for tasks such as browsing, searching, and estimating tag frequencies. In one seminal study, participants exposed to tag clouds for 60 seconds showed significantly higher recall rates for larger-font tags (72.5% recall) compared to medium (41.3%) or small (21.8%) fonts, indicating that visual prominence aids topic scanning but biases attention toward prominent items.[42] However, the same research found that tag clouds were less effective than sorted lists for forming overall impressions of tag sets, with lists achieving higher accuracy in recognition tasks (mean impression score of 2.68 versus 2.41 for spatial layouts).[42] Another evaluation revealed that while tag clouds enabled quicker searches for broad topics (average 7.1 seconds per trial) compared to traditional text search interfaces (11.6 seconds, a roughly 39% reduction), they underperformed lists in precise frequency estimation, where users overestimated smaller tags by up to 20-30% due to approximate size scaling.[43] A 2020 survey of these early studies confirms that tag clouds facilitate faster exploratory scanning than linear lists in browsing scenarios but sacrifice precision for quantitative judgments.[13] Cognitive processing of tag clouds is heavily influenced by perceptual principles, particularly size and proximity from Gestalt theory. Users tend to perceive larger tags as dominant figures, drawing initial attention and fixations according to eye-tracking data, which aligns with the figure-ground principle where prominent elements emerge from the background.[44] This size dominance enhances quick topic identification but can lead to neglect of smaller tags, reducing overall comprehension in unbalanced clouds. Dense layouts exacerbate clutter, as irregular spacing invokes the proximity principle, causing unintended visual groupings that confuse semantic relationships and increase cognitive load during scanning.[44] User interactions with tag clouds favor visually salient elements, with larger tags receiving higher selection rates due to their perceptual priority. Eye-tracking studies reveal a top-down reading bias, with 40-50% more fixations in the upper-left quadrant, reflecting Western cultural scanning patterns that prioritize this area for initial exploration.[44] This bias can improve efficiency for broad overviews but hinders uniform coverage of all tags. Accessibility challenges arise for color-blind users when color coding supplements size, as it conveys frequency without textual equivalents, violating WCAG guidelines for perceivable content. Recommendations include using semantic HTML lists for tag clouds to enable screen reader navigation, appending numerical counts (e.g., tag frequency in parentheses) to preserve relative significance, and ensuring keyboard-focusable links for all tags.[45] For visual impairments, alt-text equivalents are advised if tag clouds are rendered as images, though text-based implementations with scalable fonts better support magnification tools.[45] Task performance metrics highlight trade-offs: in comparative evaluations, tag clouds reduced search times by approximately 15-40% for exploratory tasks versus lists or search boxes, but accuracy for exact tag presence dropped by 20-30% due to visual approximations.[43][46]Modern Uses and Limitations

In contemporary data analysis, tag clouds, often interchangeably referred to as word clouds, serve as visual tools for summarizing sentiment from social media datasets, enabling quick identification of prevalent themes and emotional tones. For instance, tools like Tableau integrate word cloud generation to process textual data from customer feedback or online posts, highlighting frequent terms to reveal patterns in large-scale sentiment analysis during the 2020s.[47][48] In educational settings, they are used for text summarization by condensing reading materials or student essays into visual overviews, with studies from the early 2020s exploring their application in language learning tools.[49] As of 2024, word clouds have been integrated with large language models (LLMs) to assist in visualizing qualitative assessment data and generating common voices from text corpora.[50] Modern integrations have expanded tag clouds through AI enhancements, where machine learning algorithms automate tag generation and weighting based on semantic relevance rather than mere frequency, improving accuracy in content management systems since 2020. For example, natural language processing (NLP) models enable auto-tagging of documents, dynamically adjusting cloud layouts to reflect contextual importance in real-time applications. Geospatial visualizations represent another advancement, with the 2023 LBS tag cloud method centralizing points of interest (POIs) around user locations in location-based services, combining tag frequency with spatial clustering to depict attribute distributions like tourism hotspots.[51][24] Despite these developments, tag clouds face significant limitations in handling complex datasets, where they are often superseded by network graphs or semantic maps that better capture relationships and hierarchies in big data environments. Scalability issues arise with voluminous texts, as traditional layouts struggle to maintain readability beyond hundreds of tags, leading to cluttered outputs unsuitable for analytical depth. Bias amplification poses a further challenge, as overemphasis on high-frequency terms can perpetuate imbalances in underlying data, such as amplifying misinformation in social media corpora by visually prioritizing viral but unverified content.[52] Criticisms of tag clouds center on their prioritization of aesthetics over substantive insight, with layouts that favor visual appeal often obscuring nuanced interpretations and inefficiently using screen space. Semantic search technologies and interactive dashboards have largely replaced them for navigation and exploration tasks in web and data interfaces. Emerging research points to hybrid approaches integrating tag clouds with virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) for immersive, three-dimensional visualizations, potentially addressing spatial limitations by allowing users to interact with floating, scalable tag structures in extended environments.[53][54][55]References

- https://www.mediawiki.org/wiki/Extension:WikiCategoryTagCloud