Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A-sharp minor

View on Wikipedia| Relative key | C-sharp major |

|---|---|

| Parallel key | A-sharp major →enharmonic: B-flat major |

| Dominant key | E-sharp minor →enharmonic: F minor |

| Subdominant key | D-sharp minor |

| Enharmonic key | B-flat minor |

| Component pitches | |

| A♯, B♯, C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯, G♯ | |

A-sharp minor is a minor musical scale based on A♯, consisting of the pitches A♯, B♯, C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯, and G♯. Its key signature has seven sharps.[1]

Its relative major is C-sharp major (or enharmonically D-flat major). Its parallel major, A-sharp major, is usually replaced by B-flat major, since A-sharp major's three double-sharps make it impractical to use. The enharmonic equivalent of A-sharp minor is B-flat minor,[1] which only contains five flats and is often preferable to use.

The A-sharp natural minor scale is:

Changes needed for the melodic and harmonic versions of the scale are written in with accidentals as necessary. The A-sharp harmonic minor and melodic minor scales are:

In Christian Heinrich Rinck's 30 Preludes and Exercises in all major and minor keys, Op. 67, the 16th Prelude and Exercise and Max Reger's On the Theory of Modulation on pp. 46~50 are in A-sharp minor.[2] In Bach's Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp major, BWV 848, a brief section near the beginning of the piece modulates to A-sharp minor.

In tuning systems where the number of notes per octave is not a multiple of 12, notes such as A♯ and B♭ are not enharmonically equivalent, nor are the corresponding key signatures. For example, the key of A-sharp minor, with seven sharps, is equivalent to B-flat minor in 12-tone equal temperament, but in 19-tone equal temperament, it is equivalent to B-double flat minor instead, with 12 flats. Therefore, A-sharp minor with 7 sharps, which has been rarely used in the existing 12-tone temperament, may be absolutely necessary.

Scale degree chords

[edit]The scale degree chords of A-sharp minor are:

- Tonic – A-sharp minor

- Supertonic – B-sharp diminished

- Mediant – C-sharp major

- Subdominant – D-sharp minor

- Dominant – E-sharp minor

- Submediant – F-sharp major

- Subtonic – G-sharp major

References

[edit]External links

[edit]A-sharp minor

View on GrokipediaScale and Notation

A-sharp minor scale

The A-sharp minor scale is a seven-note diatonic scale constructed with the tonic note A♯ as its starting point, following the characteristic minor scale pattern of whole and half steps.[6] In its natural form, the scale consists of the pitches A♯, B♯, C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯, G♯, and returns to A♯ an octave higher; this variant features lowered sixth (F♯) and seventh (G♯) degrees relative to the parallel major scale, producing the interval sequence of whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole steps (W-H-W-W-H-W-W).[7][6] The harmonic minor variant modifies the natural scale by raising the seventh degree by a half step to G♯♯, yielding the pitches A♯, B♯, C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯, G♯♯, and A♯; this alteration creates a stronger leading tone (G♯♯) to facilitate the dominant chord's resolution back to the tonic.[7][6] The ascending melodic minor scale further raises the sixth degree to F♯♯, resulting in A♯, B♯, C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯♯, G♯♯, and A♯, which provides a smoother ascent toward the tonic while descending typically reverts to the natural minor form.[7][6] In notation, the A-sharp minor scale employs a key signature of seven sharps (F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯), where notes like E♯ (enharmonically F natural) and B♯ (enharmonically C natural) are written with sharps to maintain consistency with the sharp-based key, and double sharps such as F♯♯ (G natural) and G♯♯ (A natural) appear in the harmonic and melodic variants to preserve the scale's theoretical structure.[7][6] This scale is enharmonically equivalent to the B-flat minor scale, which uses flats for the same pitches.[6]Enharmonic equivalents

A-sharp minor is enharmonically equivalent to B-flat minor, meaning both keys consist of the same pitches but are notated differently: A♯ minor uses A♯, B♯, C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯, G♯, while B-flat minor uses B♭, C, D♭, E♭, F, G♭, A♭.[3][8] The key signature of A-sharp minor includes seven sharps—F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯—which often results in awkward notation, such as double sharps (e.g., E♯ for F or B♯ for C) in melodic lines and chords, making it less practical for performers and engravers.[3] In contrast, B-flat minor's five-flat signature (B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭) offers simpler, more readable notation with fewer accidentals, leading to its historical and practical preference in most musical scores.[8] A-sharp minor notation appears rarely, primarily in theoretical exercises or specific compositional contexts, such as modulations from adjacent sharp keys like E-sharp major (enharmonic to F major) to emphasize voice leading without frequent accidentals. For instance, Johann Christian Heinrich Rinck composed Prelude No. 16 in A-sharp minor as part of his Practical Organ School, Op. 55, demonstrating its use in pedagogical organ literature.[5]Key Relationships

Relative and parallel keys

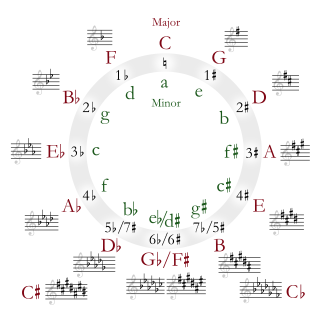

The relative major of A♯ minor is C♯ major, which shares the same key signature of seven sharps (F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯). The C♯ major scale consists of the notes C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯, G♯, A♯, B♯, and C♯.[9][10] The parallel major of A♯ minor is A♯ major, which also employs a key signature of seven sharps but features double sharps in its scale degrees to maintain the major quality. The A♯ major scale comprises the notes A♯, B♯, C𝄪, D♯, E♯, F𝄪, G𝄪, and A♯.[11][10] In A♯ minor compositions, modal mixture often involves borrowing chords from the relative major C♯ major, such as the major mediant or submediant, to introduce brighter harmonic colors while remaining within the shared key signature; this technique enhances expressiveness by blending minor-key melancholy with major-key resolution.[12]Position in the circle of fifths

A-sharp minor is situated at the seventh position clockwise from C major in the circle of fifths, following G-sharp minor in the sequence of sharp minor keys. It occupies the same position as its enharmonic equivalent B♭ minor in the flat progression, which follows F minor (4 flats) counterclockwise. This placement highlights its role in the ascending sharp-key cycle, where each step adds a sharp to the key signature, culminating in the most remote sharp position before wrapping around via enharmonic equivalents.[13] As part of the sharp-key progression, A-sharp minor employs a key signature of seven sharps (F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯), aligning it with C-sharp major, its relative major, in this extreme segment of the circle. Enharmonically equivalent to B-flat minor, which uses five flats (B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭) and occupies the fifth position in the counterclockwise flat sequence relative to D-flat major, A-sharp minor's notation often shifts to the simpler flat equivalent in practice. The progression beyond this point typically reverts to flat keys, such as the enharmonic of B minor with two sharps, emphasizing the circle's modular nature through enharmonic pairings.[13] Modulation involving A-sharp minor is most straightforward to its relative major, C-sharp major, due to their shared key signature and proximity in the circle, allowing seamless transitions via common tones or pivot chords without altering accidentals. Similarly, shifts to the dominant key of E-sharp major—enharmonically F major, located early in the clockwise sequence—facilitate harmonic resolution, as the dominant relationship spans a perfect fifth and leverages familiar terrain in the circle for smooth integration. This positioning underscores A-sharp minor's theoretical rarity, as its seven sharps render it cumbersome compared to the flat-side equivalent B-flat minor, leading composers to favor the latter for practicality in notation and performance.[14][15]Harmonic Structure

Diatonic chords

The diatonic chords of A-sharp minor are derived by stacking thirds on each degree of the natural minor scale, which consists of the notes A♯, B♯, C♯, D♯, E♯, F♯, and G♯.[16] These chords follow the standard pattern for natural minor keys: minor triads on i, iv, and v; a diminished triad on ii°; and major triads on III, VI, and VII.[17] The Roman numeral notation reflects this structure, with lowercase for minor and superscript ° for diminished.| Scale Degree | Roman Numeral | Triad | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | i | A♯ minor | A♯–C♯–E♯ |

| 2 | ii° | B♯ diminished | B♯–D♯–F♯ |

| 3 | III | C♯ major | C♯–E♯–G♯ |

| 4 | iv | D♯ minor | D♯–F♯–A♯ |

| 5 | v | E♯ minor | E♯–G♯–B♯ |

| 6 | VI | F♯ major | F♯–A♯–C♯ |

| 7 | VII | G♯ major | G♯–B♯–D♯ |

| Scale Degree | Roman Numeral | Seventh Chord | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | i7 | A♯ minor seventh | A♯–C♯–E♯–G♯ |

| 2 | ii°7 | B♯ half-diminished seventh | B♯–D♯–F♯–A♯ |

| 3 | III7 | C♯ major seventh | C♯–E♯–G♯–B♯ |

| 4 | iv7 | D♯ minor seventh | D♯–F♯–A♯–C♯ |

| 5 | v7 | E♯ minor seventh | E♯–G♯–B♯–D♯ |

| 6 | VI7 | F♯ major seventh | F♯–A♯–C♯–E♯ |

| 7 | VII7 | G♯ major seventh | G♯–B♯–D♯–F♯ |