Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Relative key

View on WikipediaIn music, 'relative keys' are the major and minor scales that have the same key signatures (enharmonically equivalent), meaning that they share all of the same notes but are arranged in a different order of whole steps and half steps. A pair of major and minor scales sharing the same key signature are said to be in a relative relationship.[1][2] The relative minor of a particular major key, or the relative major of a minor key, is the key which has the same key signature but a different tonic. (This is as opposed to parallel minor or major, which shares the same tonic.)

For example, F major and D minor both have one flat in their key signature at B♭; therefore, D minor is the relative minor of F major, and conversely F major is the relative major of D minor. The tonic of the relative minor is the sixth scale degree of the major scale, while the tonic of the relative major is the third degree of the minor scale.[1] The minor key starts three semitones below its relative major; for example, A minor is three semitones below its relative, C major.

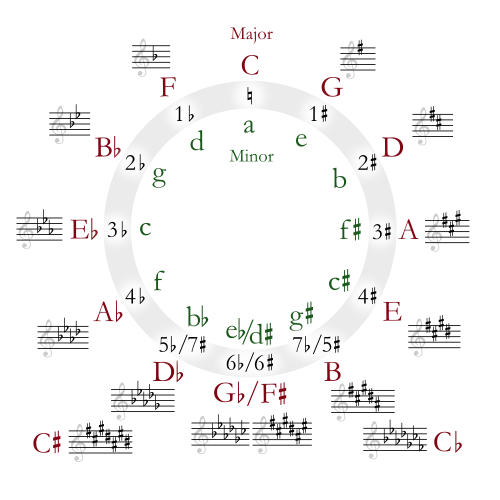

The relative relationship may be visualized through the circle of fifths.[1]

Relative keys are a type of closely related keys, the keys between which most modulations occur, because they differ by no more than one accidental. Relative keys are the most closely related, as they share exactly the same notes.[3] The major key and the minor key also share the same set of chords. In every major key, the triad built on the first degree (note) of the scale is major, the second and third are minor, the fourth and fifth are major, the sixth minor and the seventh is diminished. In the relative minor, the same triads pertain. Because of this, it can occasionally be difficult to determine whether a particular piece of music is in a major key or its relative minor.

Distinguishing on the basis of melody

[edit]To distinguish a minor key from its relative major, one can look to the first note/chord of the melody, which usually is the tonic or the dominant (fifth note); The last note/chord also tends to be the tonic. A "raised 7th" is also a strong indication of a minor scale (instead of a major scale): For example, C major and A minor both have no sharps or flats in their key signatures, but if the note G♯ (the seventh note in A minor raised by a semitone) occurs frequently in a melody, then this melody is likely in A harmonic minor, instead of C major.

List

[edit]A complete list of relative minor/major pairs in order of the circle of fifths is:

| Key signature | Major key | Minor key |

|---|---|---|

| E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭, B |

F♭ major | D♭ minor |

| B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭ | C♭ major | A♭ minor |

| B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭ | G♭ major | E♭ minor |

| B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭ | D♭ major | B♭ minor |

| B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭ | A♭ major | F minor |

| B♭, E♭, A♭ | E♭ major | C minor |

| B♭, E♭ | B♭ major | G minor |

| B♭ | F major | D minor |

| None | C major | A minor |

| F♯ | G major | E minor |

| F♯, C♯ | D major | B minor |

| F♯, C♯, G♯ | A major | F♯ minor |

| F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯ | E major | C♯ minor |

| F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯ | B major | G♯ minor |

| F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯ | F♯ major | D♯ minor |

| F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯ | C♯ major | A♯ minor |

| C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, F |

G♯ major | E♯ minor |

Terminology

[edit]In German, relative key is Paralleltonart, while parallel key is Varianttonart. Similar terminology is used in most Germanic and Slavic languages, but not in Romance languages. Adding to the confusion, a parallel chord is derived from the relative key.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Benward; Saker (2003). Music in Theory and Practice. Vol. I. McGraw-Hill. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

D flat major and a minor scale that have the same key signature are said to be in a relative relationship.

- ^ Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony (3rd ed.). Holt, Rinehart, and Wilson. p. 9. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.

The key which shares the same key signature but not the same first degree with another scale is called relative. Thus, e.g. the relative of C major is A minor (no sharps or flats in either key signature); the relative major of A minor is C major.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 243.

Relative key

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In music theory, relative keys refer to pairs of major and minor keys that share the identical key signature, meaning they employ the same set of pitches, but establish their tonal centers on different scale degrees.[7] The major key begins on the tonic (first scale degree), while its relative minor commences on the sixth scale degree of that major scale, utilizing the natural minor scale form.[7] Conversely, the relative major of a given minor key is constructed starting from the third scale degree of the minor scale.[7] This relationship ensures that both keys draw from the same collection of notes without requiring additional accidentals beyond the shared signature.[8] The core distinction between relative keys lies in their emphasis on different roots as the tonal center, despite the common pitch content, which allows composers to shift emotional or structural focus within the same diatonic framework.[9] For instance, the relative minor highlights a minor third below the major key's tonic as its new root, creating a sense of relatedness while altering the mode's character from bright and stable (major) to more introspective or tense (minor).[7] This shared pitch collection facilitates seamless transitions in composition, as no new notes are introduced.[8] A classic example is the pair of C major and A minor, both featuring no sharps or flats in their key signatures. The C major scale consists of the notes C-D-E-F-G-A-B, with C as the tonic.[7] In contrast, the A minor scale rearranges these same pitches starting from A: A-B-C-D-E-F-G, establishing A as the tonal center and deriving from the sixth degree of the C major scale.[7] This illustrates how relative keys maintain harmonic compatibility while varying the perceived key through root emphasis.Relationship to Key Signatures

Relative keys are defined by their shared key signatures, meaning that each pair consists of a major key and its corresponding minor key (or vice versa) that employ identical sets of sharps or flats. This structural equivalence ensures that the pitch collections derived from their scales are the same, differing only in the choice of tonic note. For instance, the key of G major, with a key signature of one sharp (F♯), corresponds to E minor, which uses the identical signature of one sharp (F♯).[6][9] The key signature fundamentally determines the accidentals present in the diatonic scale for both keys in a relative pair, establishing a common set of seven pitches. In the natural minor scale of the relative minor, these accidentals match exactly those of the major scale, without requiring any additional alterations such as raised leading tones or lowered submediants that might appear in harmonic or melodic minor forms. This alignment is evident in examples like C major and A minor, both of which have no sharps or flats, allowing seamless use of the same notational framework.[3][10] Consequently, transitions between relative keys in composition or analysis require no changes to the key signature, preserving the notational consistency and avoiding the enharmonic adjustments necessary for shifts to non-relative keys. This property underscores the relational harmony inherent in the tonal system, where the shared signature facilitates fluid exploration of major and minor modalities within the same pitch framework.[11][12]Identification Methods

Relative Minor of a Major Key

In the major scale, the tonic note of the relative minor is the sixth scale degree, known as the submediant.[6] This sixth degree becomes the starting point for the natural minor scale, which forms the basis of the relative minor key.[13] The interval between the tonic of the major key and the tonic of its relative minor is a minor third downward (three semitones) or, equivalently, a major sixth upward.[3] To identify the relative minor tonic, lower the major key's tonic by a minor third; for instance, starting from C major, descending three half-steps from C leads to A, establishing A minor as the relative minor.[3] These relative keys share the same key signature.[7] The following table provides examples for all twelve major keys and their relative minors, based on the natural minor scale:Relative Major of a Minor Key

In the natural minor scale, the tonic of the relative major key corresponds to the third scale degree, referred to as the mediant.[9] This relationship positions the relative major tonic a minor third above the minor tonic—or three half steps upward—or equivalently, a major sixth below.[7] The formula for identifying the relative major involves raising the minor key's tonic by a minor third; for instance, starting from A minor and ascending three half steps arrives at C as the tonic of C major.[15] The following table lists the relative major keys for all twelve minor keys, based on this interval structure and shared key signatures:| Minor Key | Relative Major Key |

|---|---|

| A minor | C major |

| B♭ minor | D♭ major |

| B minor | D major |

| C minor | E♭ major |

| C♯ minor | E major |

| D minor | F major |

| D♯ minor | F♯ major |

| E minor | G major |

| F minor | A♭ major |

| F♯ minor | A major |

| G minor | B♭ major |

| G♯ minor | B major |