Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Subdominant

View on Wikipedia

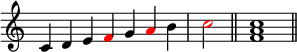

In music, the subdominant is the fourth tonal degree (![]() ) of the diatonic scale. It is so called because it is the same distance below the tonic as the dominant is above the tonic – in other words, the tonic is the dominant of the subdominant.[1][2][3] It also happens to be the note one step below the dominant.[4] In the movable do solfège system, the subdominant note is sung as fa.

) of the diatonic scale. It is so called because it is the same distance below the tonic as the dominant is above the tonic – in other words, the tonic is the dominant of the subdominant.[1][2][3] It also happens to be the note one step below the dominant.[4] In the movable do solfège system, the subdominant note is sung as fa.

The triad built on the subdominant note is called the subdominant chord. In Roman numeral analysis, the subdominant chord is typically symbolized by the Roman numeral "IV" in a major key, indicating that the chord is a major triad. In a minor key, it is symbolized by "iv", indicating that the chord is a minor triad.

In very much conventionally tonal music, harmonic analysis will reveal a broad prevalence of the primary (often triadic) harmonies: tonic, dominant, and subdominant (i.e., I and its chief auxiliaries a 5th removed), and especially the first two of these.

— Berry (1976)[5]

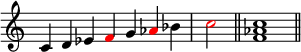

These chords may also appear as seventh chords: in major, as IVM7, or in minor as iv7 or sometimes IV7:[6]

A cadential subdominant chord followed by a tonic chord produces the so-called plagal cadence.

As with other chords which often precede the dominant, subdominant chords typically have predominant function. In Riemannian theory, it is considered to balance the dominant around the tonic (being as far below the tonic as the dominant is above).

The term subdominant may also refer to a relationship of musical keys. For example, relative to the key of C major, the key of F major is the subdominant. Music which modulates (changes key) often modulates to the subdominant when the leading tone is lowered by half step to the subtonic (B to B♭ in the key of C). Modulation to the subdominant key often creates a sense of musical relaxation, as opposed to modulation to the dominant (fifth note of the scale), which increases tension.

References

[edit]- ^ Jonas, Oswald (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker (1934: Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in Die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers), p. 22. Trans. John Rothgeb. ISBN 0-582-28227-6. "subdominant [literally, lower dominant]" emphasis original.

- ^ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 33. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0. "The lower dominant."

- ^ Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony, p. 9. 3rd edition. Holt, Rinehart, and Wilson. ISBN 0-03-020756-8. "The triad on IV is called the subdominant because it occupies a position below the tonic triad analogous to that occupied by the dominant above.

- ^ "Subdominant", Dictionary.com.

- ^ Berry, Wallace (1976/1987). Structural Functions in Music, p. 62. ISBN 0-486-25384-8.

- ^ Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy (2004). Tonal Harmony (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. p. 229. ISBN 0072852607. OCLC 51613969.

External links

[edit] Media related to Subdominant at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Subdominant at Wikimedia Commons