Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

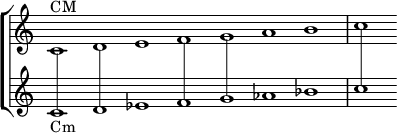

Parallel key

View on Wikipedia

In music theory, a major scale and a minor scale that have the same starting note (tonic) are called parallel keys and are said to be in a parallel relationship.[1][2] For example, G major and G minor have the same tonic (G) but have different modes, so G minor is the parallel minor of G major. This relationship is different from that of relative keys, a pair of major and minor scales that share the same notes but start on different tonics (e.g., G major and E minor).

A major scale can be transformed to its parallel minor by lowering the third, sixth, and seventh scale degrees, and a minor scale can be transformed to its parallel major by raising those same scale degrees.

In the early nineteenth century, composers began to experiment with freely borrowing chords from the parallel key.

In rock and popular music, examples of songs that emphasize parallel keys include Grass Roots' "Temptation Eyes", The Police's "Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic", Lipps Inc's "Funkytown", The Beatles' "Norwegian Wood," and Dusty Springfield's "You Don't Have To Say You Love Me".[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Benward & Saker (2003). Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.35. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0. "A major and a minor scale that have the same tonic note are said to be in parallel relationship."

- ^ Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony, p.9. 3rd edition. Holt, Rinehart, and Wilson. ISBN 0-03-020756-8. "When a major and minor scale both begin with the same note ... they are called parallel. Thus we say that the parallel major key of C minor is C major, the parallel minor of C major is C minor."

- ^ Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p.48. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

Parallel key

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Basics

Core Definition

Parallel keys in music theory refer to a pair of major and minor keys that share the same tonic note but differ in their modal structure. The major key corresponds to the Ionian mode, while the minor key corresponds to the Aeolian mode, creating a direct opposition in tonal color centered on the identical root pitch.[8][9] This shared tonic establishes the core relationship, preserving the pitch center while highlighting modal variance, which sets parallel keys apart from other tonal pairings such as relative keys that maintain the same set of pitches but shift the tonic.[1] The unchanged tonic allows composers to exploit the emotional contrast between the brighter, more stable major mode and the darker, more tense minor mode without relocating the harmonic foundation.[10] Representative examples of parallel key pairs include C major and C minor, G major and G minor, and F major and F minor, each unified by their common starting pitch.[1] At the foundation, major and minor modes are both diatonic scales—seven-note collections derived from the chromatic scale—but they diverge most notably in the quality of their third scale degree relative to the tonic: the major mode features a major third (spanning four half steps), whereas the minor mode employs a minor third (spanning three half steps). This intervallic difference profoundly influences the overall character, with the major third contributing consonance and uplift, and the minor third evoking introspection or melancholy.Key Signature Differences

In parallel keys, the minor variant requires three additional flats or the equivalent of three fewer sharps in its key signature compared to the major, primarily to lower the third, sixth, and seventh scale degrees.[6] For instance, C major uses no sharps or flats, while its parallel C minor employs three flats (E♭, A♭, B♭).[6] Similarly, F major has one flat (B♭), whereas F minor adds three more for a total of four flats (B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭).[6] Standard key signatures appear on the staff in a fixed order—sharps ascending from F♯ to C♯, and flats descending from B♭ to E♭—positioned between the clef and time signature to indicate the prevailing tonality.[11] On the circle of fifths, parallel keys align vertically, with the major key positioned on the outer ring and the minor three fifths counterclockwise on the inner ring, facilitating quick visual identification of their shared tonic.[6] Exceptions arise in keys with extreme accidentals, where enharmonic equivalents may be preferred for practicality; for example, F♯ major requires six sharps (F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯), but its parallel F♯ minor uses only three (F♯, C♯, G♯), as the natural minor scale avoids the raised leading tone and other alterations inherent to the major.[12] In such cases, composers often select the notation with fewer accidentals to aid performers, such as opting for G♭ major (six flats) over F♯ major when modulating, though parallel minors like G♭ minor would similarly prioritize the simpler F♯ minor spelling.[13] These signature differences impact sight-reading by necessitating rapid mental adjustment to altered diatonic notes, as performers must anticipate the lowered degrees in minor keys despite the shared tonic, potentially increasing cognitive load in unfamiliar signatures.[14] For transposition between parallel keys without shifting the tonic pitch—such as converting a major melody to its minor counterpart—musicians adjust only the relevant accidentals for the third, sixth, and seventh degrees, preserving the fundamental tone while altering the modal color.[15]Theoretical Relationships

Harmonic Structure

In parallel keys, which share the same tonic note but differ in mode, the harmonic structure arises from the construction of triads using scale degrees, resulting in chords of varying qualities that define the key's tonal character. Common chords such as the tonic (I in major, i in minor), subdominant (IV in major, iv in minor), and dominant (V in major, v in natural minor) maintain similar root positions but change in intervallic content due to modal differences; for instance, the tonic triad in C major consists of C-E-G (major third from root to third, minor third from third to fifth), while in C minor it is C-E♭-G (minor third from root to third, major third from third to fifth). The functional harmony of parallel keys is shaped by these alterations, particularly the lowered third scale degree in the minor mode, which forms a minor tonic triad and introduces distinct tensions and resolutions compared to the major mode's brighter, more stable tonic. This minor tonic creates a sense of melancholy or introspection, with resolutions from the dominant (V or v) emphasizing the minor third's pull rather than the major third's lift, while parallel chords—such as shifting from a C major triad to its parallel C minor triad—highlight modal mixture by preserving the root and fifth but flattening the third for coloristic effect.[16] A comprehensive comparison of the seven diatonic triads in parallel keys reveals systematic differences in chord qualities, built by stacking thirds from each scale degree. In C major, the pattern follows major-minor-minor-major-major-minor-diminished, while in C natural minor, it is minor-diminished-major-minor-minor-major-major. The table below illustrates this for the tonic C, listing chord names, Roman numerals, note components, and interval progressions from the root (all triads feature a perfect fifth from root to fifth unless diminished).| Scale Degree | C Major Triad | Roman Numeral | Notes | Interval Progression (Root to Third to Fifth) | C Minor Triad (Natural) | Roman Numeral | Notes | Interval Progression (Root to Third to Fifth) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Tonic) | C major | I | C-E-G | Major 3rd, minor 3rd | C minor | i | C-E♭-G | Minor 3rd, major 3rd |

| 2 | D minor | ii | D-F-A | Minor 3rd, major 3rd | D diminished | ii° | D-F-A♭ | Minor 3rd, minor 3rd |

| 3 | E minor | iii | E-G-B | Minor 3rd, major 3rd | E♭ major | III | E♭-G-B♭ | Major 3rd, minor 3rd |

| 4 (Subdominant) | F major | IV | F-A-C | Major 3rd, minor 3rd | F minor | iv | F-A♭-C | Minor 3rd, major 3rd |

| 5 (Dominant) | G major | V | G-B-D | Major 3rd, minor 3rd | G minor | v | G-B♭-D | Minor 3rd, major 3rd |

| 6 | A minor | vi | A-C-E | Minor 3rd, major 3rd | A♭ major | VI | A♭-C-E♭ | Major 3rd, minor 3rd |

| 7 | B diminished | vii° | B-D-F | Minor 3rd, minor 3rd | B♭ major | VII | B♭-D-F | Major 3rd, minor 3rd |