Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Abstract factory pattern

View on Wikipedia

The abstract factory pattern in software engineering is a design pattern that provides a way to create families of related objects without imposing their concrete classes, by encapsulating a group of individual factories that have a common theme without specifying their concrete classes.[1] According to this pattern, a client software component creates a concrete implementation of the abstract factory and then uses the generic interface of the factory to create the concrete objects that are part of the family. The client does not know which concrete objects it receives from each of these internal factories, as it uses only the generic interfaces of their products.[1] This pattern separates the details of implementation of a set of objects from their general usage and relies on object composition, as object creation is implemented in methods exposed in the factory interface.[2]

Use of this pattern enables interchangeable concrete implementations without changing the code that uses them, even at runtime. However, employment of this pattern, as with similar design patterns, may result in unnecessary complexity and extra work in the initial writing of code. Additionally, higher levels of separation and abstraction can result in systems that are more difficult to debug and maintain.

Overview

[edit]The abstract factory design pattern is one of the 23 patterns described in the 1994 Design Patterns book. It may be used to solve problems such as:[3]

- How can an application be independent of how its objects are created?

- How can a class be independent of how the objects that it requires are created?

- How can families of related or dependent objects be created?

Creating objects directly within the class that requires the objects is inflexible. Doing so commits the class to particular objects and makes it impossible to change the instantiation later without changing the class. It prevents the class from being reusable if other objects are required, and it makes the class difficult to test because real objects cannot be replaced with mock objects.

A factory is the location of a concrete class in the code at which objects are constructed. Implementation of the pattern intends to insulate the creation of objects from their usage and to create families of related objects without depending on their concrete classes.[2] This allows for new derived types to be introduced with no change to the code that uses the base class.

The pattern describes how to solve such problems:

- Encapsulate object creation in a separate (factory) object by defining and implementing an interface for creating objects.

- Delegate object creation to a factory object instead of creating objects directly.

This makes a class independent of how its objects are created. A class may be configured with a factory object, which it uses to create objects, and the factory object can be exchanged at runtime.

Definition

[edit]Design Patterns describes the abstract factory pattern as "an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes."[4]

Usage

[edit]The factory determines the concrete type of object to be created, and it is here that the object is actually created. However, the factory only returns a reference (in Java, for instance, by the new operator) or a pointer of an abstract type to the created concrete object.

This insulates client code from object creation by having clients request that a factory object create an object of the desired abstract type and return an abstract pointer to the object.[5]

An example is an abstract factory class DocumentCreator that provides interfaces to create a number of products (e.g., createLetter() and createResume()). The system would have any number of derived concrete versions of the DocumentCreator class such asFancyDocumentCreator or ModernDocumentCreator, each with a different implementation of createLetter() and createResume() that would create corresponding objects such asFancyLetter or ModernResume. Each of these products is derived from a simple abstract class such asLetter or Resume of which the client is aware. The client code would acquire an appropriate instance of the DocumentCreator and call its factory methods. Each of the resulting objects would be created from the same DocumentCreator implementation and would share a common theme. The client would only need to know how to handle the abstract Letter or Resume class, not the specific version that was created by the concrete factory.

As the factory only returns a reference or a pointer to an abstract type, the client code that requested the object from the factory is not aware of—and is not burdened by—the actual concrete type of the object that was created. However, the abstract factory knows the type of a concrete object (and hence a concrete factory). For instance, the factory may read the object's type from a configuration file. The client has no need to specify the type, as the type has already been specified in the configuration file. In particular, this means:

- The client code has no knowledge of the concrete type, not needing to include any header files or class declarations related to it. The client code deals only with the abstract type. Objects of a concrete type are indeed created by the factory, but the client code accesses such objects only through their abstract interfaces.[6]

- Adding new concrete types is performed by modifying the client code to use a different factory, a modification that is typically one line in one file. The different factory then creates objects of a different concrete type but still returns a pointer of the same abstract type as before, thus insulating the client code from change. This is significantly easier than modifying the client code to instantiate a new type. Doing so would require changing every location in the code where a new object is created as well as ensuring that all such code locations have knowledge of the new concrete type, for example, by including a concrete class header file. If all factory objects are stored globally in a singleton object, and all client code passes through the singleton to access the proper factory for object creation, then changing factories is as easy as changing the singleton object.[6]

Structure

[edit]UML diagram

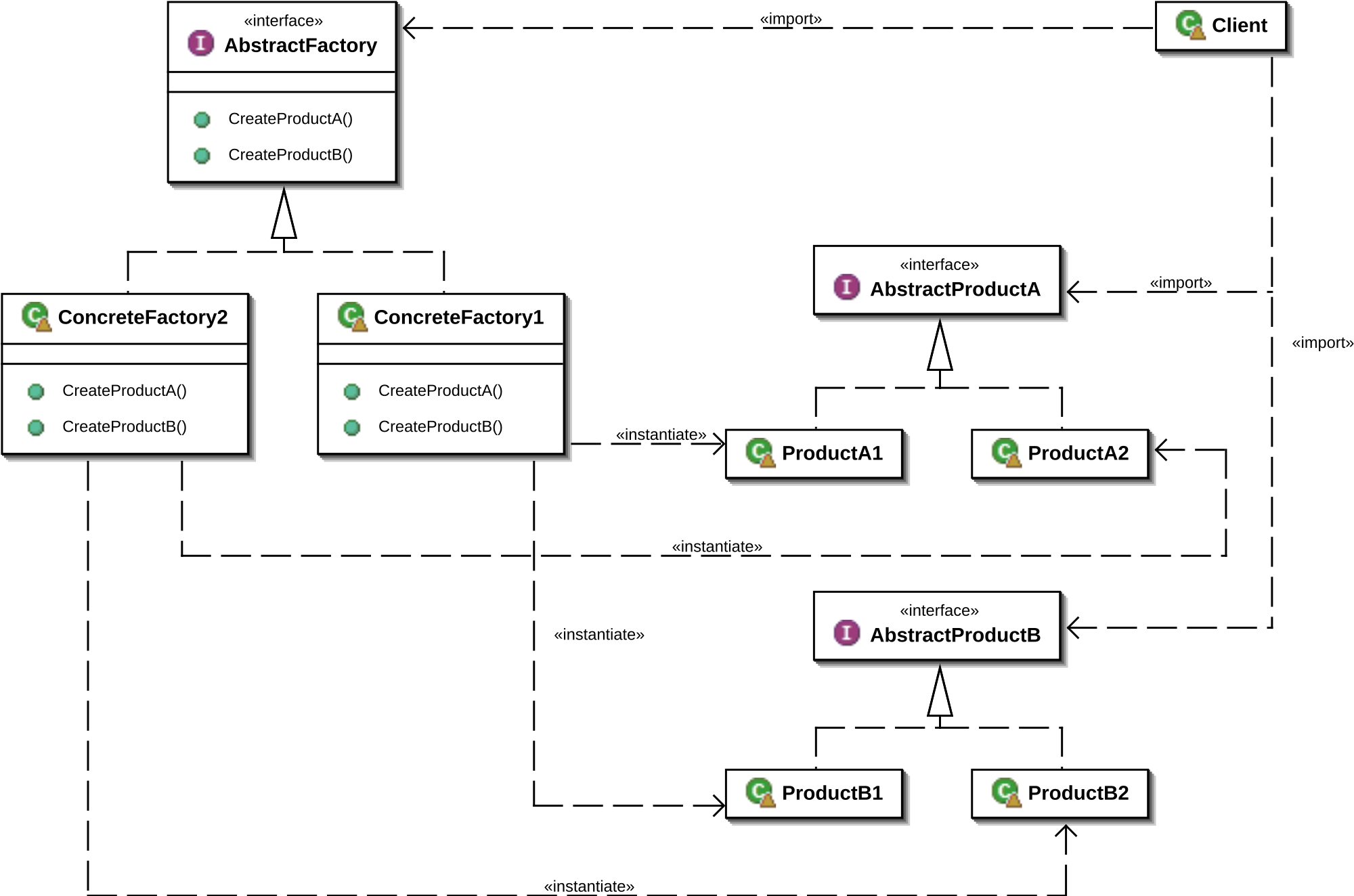

[edit]![A sample UML class and sequence diagram for the abstract factory design pattern. [7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/W3sDesign_Abstract_Factory_Design_Pattern_UML.jpg)

In the above UML class diagram,

the Client class that requires ProductA and ProductB objects does not instantiate the ProductA1 and ProductB1 classes directly. Instead, the Client refers to the AbstractFactory interface for creating objects, which makes the Client independent of how the objects are created (which concrete classes are instantiated). The Factory1 class implements the AbstractFactory interface by instantiating the ProductA1 and ProductB1 classes.

The UML sequence diagram shows the runtime interactions. The Client object calls createProductA() on the Factory1 object, which creates and returns a ProductA1 object. Thereafter, the Client calls createProductB() on Factory1, which creates and returns a ProductB1 object.

Variants

[edit]The original structure of the abstract factory pattern, as defined in 1994 in Design Patterns, is based on abstract classes for the abstract factory and the abstract products to be created. The concrete factories and products are classes that specialize the abstract classes using inheritance.[4]

A more recent structure of the pattern is based on interfaces that define the abstract factory and the abstract products to be created. This design uses native support for interfaces or protocols in mainstream programming languages to avoid inheritance. In this case, the concrete factories and products are classes that realize the interface by implementing it.[1]

Example

[edit]This C++23 implementation is based on the pre-C++98 implementation in the book.

import std;

using std::array;

using std::shared_ptr;

using std::unique_ptr;

using std::vector;

enum class Direction {

North,

South,

East,

West

};

class MapSite {

public:

virtual void enter() = 0;

virtual ~MapSite() = default;

};

class Room: public MapSite {

private:

int roomNumber;

shared_ptr<array<MapSite, 4>> sides;

public:

Room():

roomNumber{0} {}

explicit Room(int n):

roomNumber{n} {}

Room& setSide(Direction d, MapSite* ms) {

sides[static_cast<size_t>(d)] = std::move(ms);

std::println("Room::setSide {} ms", d);

return *this;

}

virtual void enter() override = 0;

Room(const Room&) = delete;

Room& operator=(const Room&) = delete;

};

class Wall: public MapSite {

public:

Wall():

MapSite() {}

explicit Wall(int n):

MapSite(n) {}

void enter() override {

// ...

}

};

class Door: public MapSite {

private:

shared_ptr<Room> room1;

shared_ptr<Room> room2;

public:

Door(shared_ptr<Room> r1 = nullptr, shared_ptr<Room> r2 = nullptr):

MapSite(), room1{std::move(r1)}, room2{std::move(r2)} {}

explicit Door(int n, shared_ptr<Room> r1 = nullptr, shared_ptr<Room> r2 = nullptr):

MapSite(n), room1{std::move(r1)}, room2{std::move(r2)} {}

void enter() override {

// ...

}

Door(const Door&) = delete;

Door& operator=(const Door&) = delete;

};

class Maze {

private:

vector<shared_ptr<Room>> rooms;

public:

Maze& addRoom(shared_ptr<Room> r) {

std::println("Maze::addRoom {}", reinterpret_cast<void*>(r.get()));

rooms.push_back(std::move(r));

return *this;

}

shared_ptr<Room> roomNo(int n) const {

for (const Room& r: rooms) {

// actual lookup logic here...

}

return nullptr;

}

};

class MazeFactory {

public:

MazeFactory() = default;

virtual ~MazeFactory() = default;

[[nodiscard]]

unique_ptr<Maze> makeMaze() const {

return std::make_unique<Maze>();

}

[[nodiscard]]

shared_ptr<Wall> makeWall() const {

return std::make_shared<Wall>();

}

[[nodiscard]]

shared_ptr<Room> makeRoom(int n) const {

return std::make_shared<Room>(new Room(n));

}

[[nodiscard]]

shared_ptr<Door> makeDoor(shared_ptr<Room> r1, shared_ptr<Room> r2) const {

return std::make_shared<Door>(std::move(r1), std::move(r2));

}

};

// If createMaze is passed an object as a parameter to use to create rooms, walls, and doors, then you can change the classes of rooms, walls, and doors by passing a different parameter. This is an example of the Abstract Factory (99) pattern.

class MazeGame {

public:

[[nodiscard]]

unique_ptr<Maze> createMaze(MazeFactory& factory) {

unique_ptr<Maze> maze = factory.makeMaze();

shared_ptr<Room> r1 = factory.makeRoom(1);

shared_ptr<Room> r2 = factory.makeRoom(2);

shared_ptr<Door> door = factory.makeDoor(r1, r2);

maze->addRoom(r1)

.addRoom(r2)

.setSide(Direction::North, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::East, door)

.setSide(Direction::South, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::West, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::North, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::East, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::South, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::West, door);

return maze;

}

};

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

MazeGame game;

unique_ptr<Maze> maze = game.createMaze(MazeFactory());

}

The program output is:

Maze::addRoom 0x1317ed0

Maze::addRoom 0x1317ef0

Room::setSide 0 0x1318340

Room::setSide 2 0x1317f10

Room::setSide 1 0x1318360

Room::setSide 3 0x1318380

Room::setSide 0 0x13183a0

Room::setSide 2 0x13183c0

Room::setSide 1 0x13183e0

Room::setSide 3 0x1317f10

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Freeman, Eric; Robson, Elisabeth; Sierra, Kathy; Bates, Bert (2004). Hendrickson, Mike; Loukides, Mike (eds.). Head First Design Patterns (paperback). Vol. 1. O'REILLY. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-596-00712-6. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ a b Freeman, Eric; Robson, Elisabeth; Sierra, Kathy; Bates, Bert (2004). Hendrickson, Mike; Loukides, Mike (eds.). Head First Design Patterns (paperback). Vol. 1. O'REILLY. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-596-00712-6. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ "The Abstract Factory design pattern - Problem, Solution, and Applicability". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- ^ a b Gamma, Erich; Richard Helm; Ralph Johnson; John M. Vlissides (2009-10-23). "Design Patterns: Abstract Factory". informIT. Archived from the original on 2012-05-16. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

Object Creational: Abstract Factory: Intent: Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Veeneman, David (2009-10-23). "Object Design for the Perplexed". The Code Project. Archived from the original on 2011-02-21. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

The factory insulates the client from changes to the product or how it is created, and it can provide this insulation across objects derived from very different abstract interfaces.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b "Abstract Factory: Implementation". OODesign.com. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ^ "The Abstract Factory design pattern - Structure and Collaboration". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

External links

[edit] Media related to Abstract factory at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abstract factory at Wikimedia Commons- Abstract Factory Abstract Factory implementation example

Abstract factory pattern

View on Grokipedia- Abstract Products: Interfaces declaring the features of basic products in the family.

- Concrete Products: Specific implementations of the abstract products.

- Abstract Factory: An interface specifying creation methods for each abstract product.

- Concrete Factories: Classes that implement the abstract factory to produce a particular product family.

- Client: Code that interacts with the abstract factory and products without knowing their concrete types.

Introduction

Overview

The Abstract Factory pattern is a creational design pattern introduced in the seminal book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides, collectively known as the Gang of Four (GoF), published in 1994.[3] This pattern addresses the need for flexible object creation in object-oriented software design by providing a unified interface for producing related objects.[4] At its core, the Abstract Factory pattern enables the creation of families of related objects without specifying their concrete classes, thereby emphasizing abstraction and decoupling the client code from implementation details.[4] This approach allows systems to create families of related or dependent objects without specifying concrete classes, supporting the interchange of product families while ensuring consistency and compatibility among the objects produced within each family.[1] As one of the 23 design patterns cataloged in the GoF book, the Abstract Factory is specifically suited for managing families of objects in contexts that require adaptability, such as cross-platform development where applications must generate platform-specific graphical user interface (GUI) components like buttons and menus that adhere to the native look and feel.[3][5] It typically involves key abstractions like an AbstractFactory interface for creation methods and AbstractProduct interfaces for the object types, though details of these components are elaborated elsewhere.[4]History and Motivation

The Abstract Factory pattern was developed in the early 1990s by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides—known as the Gang of Four (GoF)—and formalized in their 1994 book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, which documented 23 reusable solutions to common problems in object-oriented software design.[2] The authors drew from their collaborative experiences across institutions like ParcPlace Systems, IBM, and the University of Illinois, where they refined patterns through practical application in framework development. This pattern evolved from earlier factory concepts prevalent in the Smalltalk and C++ communities during the 1980s, where developers addressed object creation in graphical user interfaces and reusable frameworks, such as Gamma's ET++ toolkit and Vlissides' InterViews library.[6] These precursors, like the simpler Factory Method pattern, handled individual object instantiation but struggled with scalability in complex systems requiring coordinated creation of multiple related objects, prompting the need for a more structured approach to manage dependencies in growing software architectures.[1] The primary motivation for the Abstract Factory pattern arose from challenges in object-oriented design, including tight coupling between client code and concrete classes when directly instantiating objects, which hindered reusability and portability across varying environments.[1] In configurable systems—such as user interface toolkits supporting multiple look-and-feel standards like Motif for Unix or Presentation Manager for OS/2—direct instantiation led to inconsistent families of related objects (e.g., mismatched scroll bars, buttons, and menus), complicating adaptation to different hardware or operating systems without widespread code changes.[4] By encapsulating creation logic into interchangeable factories, the pattern ensured consistent, theme-based object families while isolating concrete implementations, thereby addressing scalability issues in large, adaptable software systems.[1]Definition and Purpose

Formal Definition

The Abstract Factory pattern is a creational design pattern that provides an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes. Here, a "family" denotes a collection of products—such as UI elements or database drivers—that are intended to interoperate seamlessly within the same context, ensuring compatibility across the set. The pattern's abstraction layer, embodied in the factory interface, decouples client code from specific implementations, permitting runtime substitution of entire product families (e.g., switching between GUI toolkits) while maintaining the same creation protocol. Key terminology distinguishes between abstract and concrete elements: the abstract factory declares a creation interface for abstract products, while concrete factories implement this to instantiate specific product variants; similarly, abstract products define object interfaces, and concrete products provide the actual implementations that form the families. This interface-based approach emphasizes polymorphism, allowing factories to be interchanged without exposing or hard-coding product details in the client.Key Objectives

The abstract factory pattern achieves its primary goals by providing a structured approach to object creation that emphasizes abstraction and long-term maintainability in software systems. By defining an interface for producing families of related objects without tying client code to specific implementations, the pattern enables developers to focus on high-level design concerns rather than low-level instantiation details.[1] A core objective is to decouple client code from concrete classes, facilitating the easy swapping of entire product families as needed for varying contexts, such as internationalization where locale-specific UI components (e.g., buttons and dialogs in different languages) must be interchanged seamlessly, or theming applications where visual styles like light or dark modes can be applied uniformly across elements. This isolation ensures that changes in product implementations do not propagate to clients, promoting flexibility and reducing maintenance overhead.[1] Another key objective is to enforce consistency among the objects created, by centralizing the production process through a factory that guarantees all items belong to the same family and are interoperable, rather than allowing scattered, ad-hoc instantiations that could lead to mismatched components. For instance, in a GUI framework, this ensures that all widgets from a given platform family (e.g., Windows or macOS) work together without compatibility issues.[1] Finally, the pattern promotes extensibility by allowing the introduction of new product families without altering existing client code, thereby adhering to the open-closed principle—which states that software entities should be open for extension but closed for modification. This is particularly valuable in evolving systems, where adding support for a new variant, such as an additional operating system theme, requires only implementing a new concrete factory rather than refactoring widespread client logic.[1]Structure

Components

The Abstract Factory pattern consists of several key participants that define its structure and enable the creation of families of related objects. The AbstractFactory is an interface or abstract class that declares a set of methods for creating abstract products, with each method corresponding to a type of product in the family, such ascreateButton() and createMenu() for GUI components.[1] This interface ensures that factories from different families can be used interchangeably without altering client code.

A ConcreteFactory implements the AbstractFactory interface and is responsible for creating specific instances of concrete products that belong to a particular family, for example, a WindowsFactory that produces Windows-specific buttons and menus.[1] Each concrete factory is tailored to a specific variant or theme, ensuring that the products it creates are compatible and cohesive within that family.

The AbstractProduct defines an interface or abstract class for a type of product that may be created by the factory, specifying the operations that all concrete products of that type must implement, such as drawing methods for UI elements.[1] This abstraction allows clients to work with products without depending on their concrete implementations.

A ConcreteProduct provides the specific implementation of the AbstractProduct interface, representing a particular variant produced by a corresponding concrete factory, like a WindowsButton that adheres to Windows styling conventions.[1] Concrete products are grouped such that those from the same family work together seamlessly.

The Client is the code that utilizes the AbstractFactory to create products and interacts only with the abstract interfaces of factories and products, thereby remaining independent of concrete classes and enabling easy substitution of product families.[1]

In terms of relationships, concrete factories create concrete products via the methods declared in the AbstractFactory, while clients depend solely on the AbstractFactory and AbstractProduct interfaces, promoting decoupling and adherence to the principle of programming to abstractions.[1] This structure allows the client to configure the system with different product families at runtime or compile time without modifications.[1]

UML Diagrams

The UML class diagram for the Abstract Factory pattern visually represents the static structure of its components and their relationships, emphasizing abstraction and polymorphism to create families of related objects. The diagram features an AbstractFactory as an abstract class or interface with pure virtual methods likecreateProductA() and createProductB(), each designed to return instances of corresponding abstract product types without specifying concrete classes. Extending or implementing this are ConcreteFactory1 and ConcreteFactory2, which provide concrete implementations of these methods; for instance, ConcreteFactory1's createProductA() returns a ConcreteProductA1 instance. On the product side, AbstractProductA and AbstractProductB serve as abstract classes or interfaces defining the common operations for each product family, realized by concrete classes such as ConcreteProductA1, ConcreteProductA2, ConcreteProductB1, and ConcreteProductB2, where products from the same concrete factory (e.g., A1 and B1) are compatible variants for a specific context like a GUI toolkit or platform.[1][7]

Relationships in the class diagram are denoted using standard UML notations to clarify hierarchies and dependencies. Generalization relationships—indicating inheritance or interface realization—are shown with solid lines ending in hollow arrowheads, connecting concrete factories to the AbstractFactory and concrete products to their respective abstract products. Associations between factories and products are often implied through the factory methods rather than explicit links, as the creation is handled internally; however, if shown, they use solid lines with diamonds to denote composition or aggregation. The Client class depends on the AbstractFactory and abstract products but not on concrete implementations, illustrated by dashed lines with open arrowheads for dependency relationships, ensuring the client remains decoupled from specific classes. This structure avoids direct client-to-concrete-product links, promoting flexibility for swapping product families at runtime.[1][7]

The sequence diagram complements the class diagram by depicting the runtime interactions that demonstrate the pattern's creational flow. It begins with the Client obtaining an instance of a ConcreteFactory (typically through configuration or another creator), followed by the client invoking factory methods like createProductA() and createProductB() on the concrete factory via the abstract interface. The concrete factory then instantiates and returns ConcreteProductA and ConcreteProductB objects, which the client uses through their abstract interfaces for operations like useA() or useB(), without direct knowledge of the concrete types. Key notations include solid arrows for synchronous method calls (e.g., from client to factory and factory to product creation) and dashed arrows with open heads for return messages, highlighting the polymorphic dispatch and the absence of tight coupling between client and products. This diagram underscores how the pattern enables consistent product families while isolating creation logic.[1][7]

Variants

The Abstract Factory pattern can be adapted in various ways to suit specific language features, implementation needs, or environmental constraints, while preserving its core goal of creating families of related objects. These variants modify the standard components, such as the AbstractFactory and AbstractProduct, to provide flexibility in partial implementations, dynamic behavior, or resource management.[7] One common variant replaces interfaces with abstract classes for the AbstractFactory and AbstractProduct roles, enabling partial implementations of factory methods or product behaviors without requiring full concretization in subclasses. This approach is particularly useful in object-oriented languages where abstract classes support shared code, such as providing default creation logic in the factory or common functionality in products. For instance, in Java implementations like the Data Access Object (DAO) pattern, an abstract class serves as the DAO factory to construct concrete factories for different data sources, allowing subclasses to override only specific methods while inheriting others.[8] This variant applies in scenarios where languages or frameworks favor abstract classes for extensibility, or when avoiding the limitations of pure interfaces, such as the inability to include state or non-public members prior to features like default methods in Java 8.[7] A hybrid variant combines the Abstract Factory with the Singleton pattern for concrete factory instances, particularly in resource-constrained environments like embedded systems, where creating multiple factory objects would consume excessive memory or processing power. In this setup, each concrete factory is implemented as a singleton, ensuring a single global instance per family while the abstract factory interface remains unchanged, thus maintaining the pattern's encapsulation benefits without redundant instantiations. This combination is useful for applications with limited resources, such as middleware frameworks or device drivers, where global access to a sole factory instance optimizes performance and resource usage.[9][10]Implementation

Pseudocode

The pseudocode for the Abstract Factory pattern provides a high-level, language-independent representation of its structure and behavior, emphasizing the creation of families of related objects without specifying their concrete classes. This outline follows the original formulation in the foundational text on software design patterns, which defines the pattern's intent to provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.[3] The core components include an abstract factory interface that declares methods for creating abstract products, concrete factory implementations that instantiate specific product variants, and client code that relies on the abstract factory without direct knowledge of concrete classes.// Abstract Factory interface

interface AbstractFactory {

AbstractProductA createProductA();

AbstractProductB createProductB();

}

// Concrete Factory for one variant (e.g., Factory1)

class ConcreteFactory1 implements AbstractFactory {

AbstractProductA createProductA() {

return new ConcreteProductA1();

}

AbstractProductB createProductB() {

return new ConcreteProductB1();

}

}

// Concrete Factory for another variant (e.g., Factory2)

class ConcreteFactory2 implements AbstractFactory {

AbstractProductA createProductA() {

return new ConcreteProductA2();

}

AbstractProductB createProductB() {

return new ConcreteProductB2();

}

}

// Abstract Factory interface

interface AbstractFactory {

AbstractProductA createProductA();

AbstractProductB createProductB();

}

// Concrete Factory for one variant (e.g., Factory1)

class ConcreteFactory1 implements AbstractFactory {

AbstractProductA createProductA() {

return new ConcreteProductA1();

}

AbstractProductB createProductB() {

return new ConcreteProductB1();

}

}

// Concrete Factory for another variant (e.g., Factory2)

class ConcreteFactory2 implements AbstractFactory {

AbstractProductA createProductA() {

return new ConcreteProductA2();

}

AbstractProductB createProductB() {

return new ConcreteProductB2();

}

}

// Client usage

function getFactory(type) {

if (type == "Variant1") {

return new ConcreteFactory1();

} else if (type == "Variant2") {

return new ConcreteFactory2();

}

// Default or error handling

}

// Example client interaction

AbstractFactory factory = getFactory(OS); // e.g., OS == "Windows" selects WindowsFactory

AbstractProductA productA = factory.createProductA();

AbstractProductB productB = factory.createProductB();

productA.use();

productB.use();

// Client usage

function getFactory(type) {

if (type == "Variant1") {

return new ConcreteFactory1();

} else if (type == "Variant2") {

return new ConcreteFactory2();

}

// Default or error handling

}

// Example client interaction

AbstractFactory factory = getFactory(OS); // e.g., OS == "Windows" selects WindowsFactory

AbstractProductA productA = factory.createProductA();

AbstractProductB productB = factory.createProductB();

productA.use();

productB.use();

Language-Specific Example

To illustrate the Abstract Factory pattern in practice, consider a Java implementation for creating cross-platform graphical user interface (GUI) components, such as buttons and checkboxes tailored to Windows or macOS environments. This example defines abstract product interfaces for the components, an abstract factory interface for their creation, concrete factories that produce platform-specific implementations, and a client application that dynamically selects the factory based on the operating system, demonstrating runtime polymorphism without tight coupling to concrete classes.[11] The abstract products are represented by theButton and Checkbox interfaces, each declaring a paint() method to render the component.

public interface Button {

void paint();

}

public interface Checkbox {

void paint();

}

public interface Button {

void paint();

}

public interface Checkbox {

void paint();

}

public class WindowsButton implements Button {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created WindowsButton.");

}

}

public class WindowsCheckbox implements Checkbox {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created WindowsCheckbox.");

}

}

public class WindowsButton implements Button {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created WindowsButton.");

}

}

public class WindowsCheckbox implements Checkbox {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created WindowsCheckbox.");

}

}

public class MacButton implements Button {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created MacButton.");

}

}

public class MacCheckbox implements Checkbox {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created MacCheckbox.");

}

}

public class MacButton implements Button {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created MacButton.");

}

}

public class MacCheckbox implements Checkbox {

@Override

public void paint() {

System.out.println("You have created MacCheckbox.");

}

}

GUIFactory, declares methods to create each type of product, ensuring families of related objects are produced together.

public interface GUIFactory {

Button createButton();

Checkbox createCheckbox();

}

public interface GUIFactory {

Button createButton();

Checkbox createCheckbox();

}

WindowsFactory:

public class WindowsFactory implements GUIFactory {

@Override

public Button createButton() {

return new WindowsButton();

}

@Override

public Checkbox createCheckbox() {

return new WindowsCheckbox();

}

}

public class WindowsFactory implements GUIFactory {

@Override

public Button createButton() {

return new WindowsButton();

}

@Override

public Checkbox createCheckbox() {

return new WindowsCheckbox();

}

}

MacFactory:

public class MacFactory implements GUIFactory {

@Override

public Button createButton() {

return new MacButton();

}

@Override

public Checkbox createCheckbox() {

return new MacCheckbox();

}

}

public class MacFactory implements GUIFactory {

@Override

public Button createButton() {

return new MacButton();

}

@Override

public Checkbox createCheckbox() {

return new MacCheckbox();

}

}

Application class, depends on the abstract factory to create and use components polymorphically, invoking their methods without knowledge of concrete types. This allows the same client code to work across platforms.

public class Application {

private Button button;

private Checkbox checkbox;

public Application(GUIFactory factory) {

this.button = factory.createButton();

this.checkbox = factory.createCheckbox();

}

public void paint() {

button.paint();

checkbox.paint();

}

}

public class Application {

private Button button;

private Checkbox checkbox;

public Application(GUIFactory factory) {

this.button = factory.createButton();

this.checkbox = factory.createCheckbox();

}

public void paint() {

button.paint();

checkbox.paint();

}

}

System.getProperty("os.name") to instantiate the appropriate factory, then creates and renders the UI elements.

public class Demo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String osName = System.getProperty("os.name").toLowerCase();

GUIFactory factory;

if (osName.contains("win")) {

factory = new WindowsFactory();

} else {

factory = new MacFactory();

}

Application app = new Application(factory);

app.paint();

}

}

public class Demo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String osName = System.getProperty("os.name").toLowerCase();

GUIFactory factory;

if (osName.contains("win")) {

factory = new WindowsFactory();

} else {

factory = new MacFactory();

}

Application app = new Application(factory);

app.paint();

}

}