Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Strategy pattern

View on WikipediaIn computer programming, the strategy pattern (also known as the policy pattern) is a behavioral software design pattern that enables selecting an algorithm at runtime. Instead of implementing a single algorithm directly, code receives runtime instructions as to which in a family of algorithms to use.[1]

Strategy lets the algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.[2] Strategy is one of the patterns included in the influential book Design Patterns by Gamma et al.[3] that popularized the concept of using design patterns to describe how to design flexible and reusable object-oriented software. Deferring the decision about which algorithm to use until runtime allows the calling code to be more flexible and reusable.

For instance, a class that performs validation on incoming data may use the strategy pattern to select a validation algorithm depending on the type of data, the source of the data, user choice, or other discriminating factors. These factors are not known until runtime and may require radically different validation to be performed. The validation algorithms (strategies), encapsulated separately from the validating object, may be used by other validating objects in different areas of the system (or even different systems) without code duplication.

Typically, the strategy pattern stores a reference to code in a data structure and retrieves it. This can be achieved by mechanisms such as the native function pointer, the first-class function, classes or class instances in object-oriented programming languages, or accessing the language implementation's internal storage of code via reflection.

Structure

[edit]UML class and sequence diagram

[edit]

In the above UML class diagram, the Context class does not implement an algorithm directly.

Instead, Context refers to the Strategy interface for performing an algorithm (strategy.algorithm()), which makes Context independent of how an algorithm is implemented.

The Strategy1 and Strategy2 classes implement the Strategy interface, that is, implement (encapsulate) an algorithm.

The UML sequence diagram

shows the runtime interactions: The Context object delegates an algorithm to different Strategy objects. First, Context calls algorithm() on a Strategy1 object,

which performs the algorithm and returns the result to Context.

Thereafter, Context changes its strategy and calls algorithm() on a Strategy2 object,

which performs the algorithm and returns the result to Context.

Class diagram

[edit]

Strategy and open–closed principle

[edit]

According to the strategy pattern, the behaviors of a class should not be inherited. Instead, they should be encapsulated using interfaces. This is compatible with the open–closed principle (OCP), which proposes that classes should be open for extension but closed for modification.

As an example, consider a car class. Two possible functionalities for car are brake and accelerate. Since accelerate and brake behaviors change frequently between models, a common approach is to implement these behaviors in subclasses. This approach has significant drawbacks; accelerate and brake behaviors must be declared in each new car model. The work of managing these behaviors increases greatly as the number of models increases, and requires code to be duplicated across models. Additionally, it is not easy to determine the exact nature of the behavior for each model without investigating the code in each.

The strategy pattern uses composition instead of inheritance. In the strategy pattern, behaviors are defined as separate interfaces and specific classes that implement these interfaces. This allows better decoupling between the behavior and the class that uses the behavior. The behavior can be changed without breaking the classes that use it, and the classes can switch between behaviors by changing the specific implementation used without requiring any significant code changes. Behaviors can also be changed at runtime as well as at design-time. For instance, a car object's brake behavior can be changed from BrakeWithABS() to Brake() by changing the brakeBehavior member to:

Brake* brakeBehavior = new Brake();

package org.wikipedia.examples;

/* Encapsulated family of Algorithms

* Interface and its implementations

*/

interface IBrakeBehavior {

public void brake();

}

class BrakeWithABS implements IBrakeBehavior {

public void brake() {

System.out.println("Brake with ABS applied");

}

}

class Brake implements IBrakeBehavior {

public void brake() {

System.out.println("Simple Brake applied");

}

}

// Client that can use the algorithms above interchangeably

abstract class Car {

private IBrakeBehavior brakeBehavior;

public Car(IBrakeBehavior brakeBehavior) {

this.brakeBehavior = brakeBehavior;

}

public void applyBrake() {

brakeBehavior.brake();

}

public void setBrakeBehavior(IBrakeBehavior brakeType) {

this.brakeBehavior = brakeType;

}

}

// Client 1 uses one algorithm (Brake) in the constructor

class Sedan extends Car {

public Sedan() {

super(new Brake());

}

}

// Client 2 uses another algorithm (BrakeWithABS) in the constructor

class SUV extends Car {

public SUV() {

super(new BrakeWithABS());

}

}

// Using the Car example

public class CarExample {

public static void main(String[] arguments) {

Car sedanCar = new Sedan();

sedanCar.applyBrake(); // This will invoke class "Brake"

Car suvCar = new SUV();

suvCar.applyBrake(); // This will invoke class "BrakeWithABS"

// set brake behavior dynamically

suvCar.setBrakeBehavior(new Brake());

suvCar.applyBrake(); // This will invoke class "Brake"

}

}

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Strategy design pattern - Problem, Solution, and Applicability". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ Eric Freeman, Elisabeth Freeman, Kathy Sierra and Bert Bates, Head First Design Patterns, First Edition, Chapter 1, Page 24, O'Reilly Media, Inc, 2004. ISBN 978-0-596-00712-6

- ^ Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, John Vlissides (1994). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison Wesley. pp. 315ff. ISBN 0-201-63361-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Strategy design pattern - Structure and Collaboration". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ "Design Patterns Quick Reference – McDonaldLand".

External links

[edit]- Strategy Pattern in UML (in Spanish)

- Geary, David (April 26, 2002). "Strategy for success". Java Design Patterns. JavaWorld. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- Strategy Pattern for C article

- Refactoring: Replace Type Code with State/Strategy

- The Strategy Design Pattern at the Wayback Machine (archived 2017-04-15) Implementation of the Strategy pattern in JavaScript

Strategy pattern

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Intent

Definition

The Strategy pattern is a behavioral design pattern that defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each one as an object, and makes them interchangeable within the context of a client, allowing the algorithm to vary independently from clients that use it.[3] It consists of three key components: the Context, which is the client class that uses a Strategy; the Strategy, an interface or abstract class that declares the algorithm to be implemented; and ConcreteStrategy, concrete classes that implement the Strategy interface to provide specific algorithm behaviors.[3] The pattern was introduced in the 1994 book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides, commonly known as the Gang of Four.[3] As a behavioral design pattern, it focuses on the communication between objects, using inheritance and composition to manage algorithms and responsibilities.[3]Intent and Motivation

The intent of the Strategy pattern is to define a family of algorithms, encapsulate each one within its own class, and make them interchangeable at runtime, allowing the algorithm to vary independently from the clients that use it.[4] This pattern is motivated by scenarios where a single class must perform different behaviors based on varying conditions, such as selecting among multiple algorithms depending on input data or environmental factors. Without Strategy, such flexibility often results in bloated code filled with conditional statements (e.g., numerousif-else branches to choose between sorting algorithms like quicksort for large datasets or insertion sort for small ones), which violates the single responsibility principle and makes maintenance difficult.[5][6]

By delegating algorithm selection and execution to interchangeable strategy objects, the pattern separates the concerns of behavior choice from the core logic of the context class, reducing complexity and enabling runtime swaps without client-side modifications.[4]

A practical example is a payment processing system that must handle diverse methods like credit card authorization or PayPal integration; embedding each method's logic directly in the processor class would lead to entangled code, whereas treating them as strategies allows seamless addition or substitution of payment options.[5]

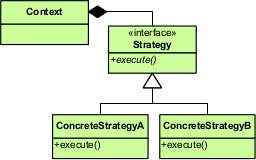

Structure

Class Diagram

The class diagram of the Strategy pattern depicts a static structure that supports the encapsulation and interchangeability of algorithms through object composition and polymorphism. As outlined in the foundational work on design patterns, the diagram features a small set of interrelated classes without complex hierarchies. The primary components include the Context class, which represents the client that uses the algorithm; the Strategy abstract class or interface; and one or more ConcreteStrategy classes. The Context class contains a private reference to a Strategy object, typically namedstrategy, and includes a public method such as contextInterface() that delegates the core algorithmic work by invoking the Strategy's algorithmInterface() method.[4][7]

The Strategy component declares the abstract algorithmInterface() method, serving as the common contract for all algorithm variants without providing an implementation itself. Each ConcreteStrategy class, such as ConcreteStrategyA or ConcreteStrategyB, implements this method with a specific algorithm, enabling diverse behaviors like sorting via quicksort or mergesort.[4][7]

Key relationships in the diagram consist of a composition association (denoted by a filled diamond) from Context to Strategy, signifying that the Context owns and manages the lifecycle of its Strategy instance; and realization relationships (dashed arrows with hollow triangles) from each ConcreteStrategy to Strategy, indicating implementation of the abstract method. Notably, no inheritance exists between Context and Strategy, preserving their independence.[4][7]

This arrangement facilitates polymorphism, where the Context interacts solely with the Strategy interface, allowing seamless substitution of ConcreteStrategy instances at runtime without modifying the Context code.[7][4]

A frequent variation replaces the Strategy interface with an abstract class to accommodate shared helper methods or default implementations across ConcreteStrategies, such as common preprocessing steps, while still supporting multiple concrete realizations.[4]

Sequence Diagram

The sequence diagram for the Strategy pattern depicts the runtime interactions that enable interchangeable algorithms, focusing on how the Client configures the Context with a specific strategy and how the Context delegates execution without knowledge of the concrete implementation. As defined in the seminal work by Gamma et al., the diagram includes lifelines for the Client (which initiates the process), the Context (which maintains a reference to the Strategy interface), the abstract Strategy, and one or more ConcreteStrategy instances (which provide the actual algorithmic behavior). The primary flow begins with the Client instantiating a ConcreteStrategy object and passing it to the Context via a setter method, such assetStrategy(). This establishes the polymorphic reference in the Context. Subsequently, the Client sends a request message to the Context, prompting the Context to invoke the execute() or equivalent algorithm method on its Strategy reference. The call resolves dynamically to the ConcreteStrategy's implementation, where the specific algorithm is performed, and the result is returned through the delegation chain back to the Client. This interaction highlights runtime polymorphism and encapsulation of implementation details within the strategy objects.

Key messages in the sequence include:

Client → ConcreteStrategy: new ConcreteStrategy()(instantiation)Client → Context: setStrategy(ConcreteStrategy)(configuration)Client → Context: request()(initiation)Context → Strategy: execute()(delegation)Strategy → self: performAlgorithm()(execution in concrete class, often shown as an activation bar on the ConcreteStrategy lifeline)

setStrategy(new DifferentConcreteStrategy) after an initial request, followed by a second request() that now delegates to the updated strategy, allowing runtime adaptability without modifying the Context. This is particularly evident in the book's motivational example of varying text justification algorithms, where the Context (e.g., a Composer) can switch between ConcreteStrategies like LeftJustify and CenterJustify based on formatting requirements.[1]

Implementation

Pseudocode

The Strategy pattern is typically implemented through an abstract strategy interface, concrete strategy classes, a context class that delegates to the strategy, and client code that configures and uses the context. This pseudocode provides a language-agnostic outline of the pattern's structure, emphasizing the encapsulation of interchangeable algorithms.[4]Strategy Interface

The core of the pattern is an abstractStrategy component defining a common interface for all supported algorithms.

interface Strategy {

algorithm(): result;

}

interface Strategy {

algorithm(): result;

}

algorithm() that concrete implementations must provide, allowing the context to invoke algorithms uniformly without knowing their specifics.[4]

Concrete Strategies

Concrete strategy classes implement theStrategy interface with specific algorithm logic. For example, two variants might sort data in ascending or descending order.

class ConcreteStrategyA implements Strategy {

algorithm(): result {

// Specific logic for algorithm A, e.g., sort ascending

return "sorted ascending";

}

}

class ConcreteStrategyB implements Strategy {

algorithm(): result {

// Specific logic for algorithm B, e.g., sort descending

return "sorted descending";

}

}

class ConcreteStrategyA implements Strategy {

algorithm(): result {

// Specific logic for algorithm A, e.g., sort ascending

return "sorted ascending";

}

}

class ConcreteStrategyB implements Strategy {

algorithm(): result {

// Specific logic for algorithm B, e.g., sort descending

return "sorted descending";

}

}

Context Class

TheContext maintains a reference to a Strategy object and delegates algorithm execution to it, promoting flexibility in behavior.

class Context {

private Strategy strategy;

constructor(Strategy initialStrategy) {

this.strategy = initialStrategy;

}

setStrategy(Strategy newStrategy) {

this.strategy = newStrategy;

}

contextMethod(): result {

if (this.strategy == null) {

throw new Error("No strategy assigned");

}

return this.strategy.algorithm();

}

}

class Context {

private Strategy strategy;

constructor(Strategy initialStrategy) {

this.strategy = initialStrategy;

}

setStrategy(Strategy newStrategy) {

this.strategy = newStrategy;

}

contextMethod(): result {

if (this.strategy == null) {

throw new Error("No strategy assigned");

}

return this.strategy.algorithm();

}

}

contextMethod() ensures the strategy is not null before delegation to prevent runtime errors, then invokes the algorithm.[4]

Client Usage

A client instantiates concrete strategies, assigns them to a context, and invokes the context's method to execute the selected algorithm.class Client {

main() {

strategyA = new ConcreteStrategyA();

[context](/page/Context) = new [Context](/page/Context)(strategyA);

resultA = [context](/page/Context).contextMethod(); // Uses ascending sort

strategyB = new ConcreteStrategyB();

[context](/page/Context).setStrategy(strategyB);

resultB = [context](/page/Context).contextMethod(); // Switches to descending sort

}

}

class Client {

main() {

strategyA = new ConcreteStrategyA();

[context](/page/Context) = new [Context](/page/Context)(strategyA);

resultA = [context](/page/Context).contextMethod(); // Uses ascending sort

strategyB = new ConcreteStrategyB();

[context](/page/Context).setStrategy(strategyB);

resultB = [context](/page/Context).contextMethod(); // Switches to descending sort

}

}

Language-Specific Example

The Strategy pattern is commonly implemented in Java, an object-oriented language well-suited for demonstrating behavioral design patterns through interfaces and polymorphism. The following example adapts the abstract pseudocode structure to concrete Java syntax, using simple arithmetic operations (addition and subtraction) to show how interchangeable strategies can be applied within a context class.[8]Strategy Interface

TheStrategy interface defines the contract for all concrete strategies, specifying a single method to execute the algorithm with two integer parameters.

public interface Strategy {

int execute(int a, int b);

}

public interface Strategy {

int execute(int a, int b);

}

Concrete Strategies

Concrete strategy classes implement theStrategy interface, each encapsulating a specific operation.

Addition Strategy:

public class ConcreteAdd implements Strategy {

@Override

public int execute(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

}

public class ConcreteAdd implements Strategy {

@Override

public int execute(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

}

public class ConcreteSubtract implements Strategy {

@Override

public int execute(int a, int b) {

return a - b;

}

}

public class ConcreteSubtract implements Strategy {

@Override

public int execute(int a, int b) {

return a - b;

}

}

Context Class

TheContext class maintains a reference to a Strategy object and provides methods to set the strategy and delegate execution to it.

public class Context {

private Strategy strategy;

public Context() {

// Default strategy can be set here if needed

}

public void setStrategy(Strategy strategy) {

this.strategy = strategy;

}

public int executeStrategy(int a, int b) {

if (strategy == null) {

throw new IllegalStateException("No strategy set");

}

return strategy.execute(a, b);

}

}

public class Context {

private Strategy strategy;

public Context() {

// Default strategy can be set here if needed

}

public void setStrategy(Strategy strategy) {

this.strategy = strategy;

}

public int executeStrategy(int a, int b) {

if (strategy == null) {

throw new IllegalStateException("No strategy set");

}

return strategy.execute(a, b);

}

}

Client Usage

In the client code, aContext instance is created, and different strategies are set and executed at runtime to demonstrate interchangeability. The output shows the results of applying addition and then subtraction to the same inputs.

public class Client {

public static void main(String[] args) {

[Context](/page/Context) context = new [Context](/page/Context)();

// Use [addition](/page/Addition) [strategy](/page/Strategy)

[Strategy](/page/Strategy) addStrategy = new ConcreteAdd();

context.setStrategy(addStrategy);

System.out.println("10 + 5 = " + context.executeStrategy(10, 5)); // Output: 10 + 5 = 15

// Switch to subtraction [strategy](/page/Strategy)

[Strategy](/page/Strategy) subtractStrategy = new ConcreteSubtract();

context.setStrategy(subtractStrategy);

System.out.println("10 - 5 = " + context.executeStrategy(10, 5)); // Output: 10 - 5 = 5

}

}

public class Client {

public static void main(String[] args) {

[Context](/page/Context) context = new [Context](/page/Context)();

// Use [addition](/page/Addition) [strategy](/page/Strategy)

[Strategy](/page/Strategy) addStrategy = new ConcreteAdd();

context.setStrategy(addStrategy);

System.out.println("10 + 5 = " + context.executeStrategy(10, 5)); // Output: 10 + 5 = 15

// Switch to subtraction [strategy](/page/Strategy)

[Strategy](/page/Strategy) subtractStrategy = new ConcreteSubtract();

context.setStrategy(subtractStrategy);

System.out.println("10 - 5 = " + context.executeStrategy(10, 5)); // Output: 10 - 5 = 5

}

}

Context to remain agnostic to the specific strategy used, as it interacts solely through the Strategy reference. The code compiles with standard Java compilers (e.g., javac from JDK 8 or later) and runs without additional dependencies, producing the expected output when executed via java Client. Extending the example to include more operations, such as multiplication, would involve adding new classes implementing Strategy without modifying existing code.