Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interpreter pattern

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

In computer programming, the interpreter pattern is a design pattern that specifies how to evaluate sentences in a language. The basic idea is to have a class for each symbol (terminal or nonterminal) in a specialized computer language. The syntax tree of a sentence in the language is an instance of the composite pattern and is used to evaluate (interpret) the sentence for a client.[1]: 243 See also Composite pattern.

Overview

[edit]The Interpreter [2] design pattern is one of the twenty-three well-known GoF design patterns that describe how to solve recurring design problems to design flexible and reusable object-oriented software, that is, objects that are easier to implement, change, test, and reuse.

What problems can the Interpreter design pattern solve?

[edit]Source:[3]

- A grammar for a simple language should be defined

- so that sentences in the language can be interpreted.

When a problem occurs very often, it could be considered to represent it as a sentence in a simple language (Domain Specific Languages) so that an interpreter can solve the problem by interpreting the sentence.

For example, when many different or complex search expressions must be specified. Implementing (hard-wiring) them directly into a class is inflexible because it commits the class to particular expressions and makes it impossible to specify new expressions or change existing ones independently from (without having to change) the class.

What solution does the Interpreter design pattern describe?

[edit]- Define a grammar for a simple language by defining an

Expressionclass hierarchy and implementing aninterpret()operation. - Represent a sentence in the language by an abstract syntax tree (AST) made up of

Expressioninstances. - Interpret a sentence by calling

interpret()on the AST.

The expression objects are composed recursively into a composite/tree structure that is called

abstract syntax tree (see Composite pattern).

The Interpreter pattern doesn't describe how

to build an abstract syntax tree. This can

be done either manually by a client or automatically by a parser.

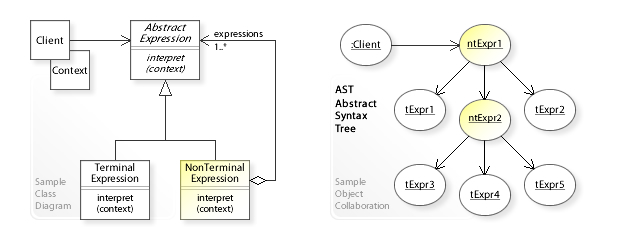

See also the UML class and object diagram below.

Uses

[edit]- Specialized database query languages such as SQL.

- Specialized computer languages that are often used to describe communication protocols.

- Most general-purpose computer languages actually incorporate several specialized languages[citation needed].

Structure

[edit]UML class and object diagram

[edit]

In the above UML class diagram, the Client class refers to the common AbstractExpression interface for interpreting an expression

interpret(context).

The TerminalExpression class has no children and interprets an expression directly.

The NonTerminalExpression class maintains a container of child expressions

(expressions) and forwards interpret requests

to these expressions.

The object collaboration diagram

shows the run-time interactions: The Client object sends an interpret request to the abstract syntax tree.

The request is forwarded to (performed on) all objects downwards the tree structure.

The NonTerminalExpression objects (ntExpr1,ntExpr2) forward the request to their child expressions.

The TerminalExpression objects (tExpr1,tExpr2,…) perform the interpretation directly.

UML class diagram

[edit]Example

[edit]This C++23 implementation is based on the pre C++98 sample code in the book.

import std;

using String = std::string;

template <typename K, typename V>

using TreeMap = std::map<K, V>;

template <typename T>

using UniquePtr = std::unique_ptr<T>;

class BooleanExpression {

public:

BooleanExpression() = default;

virtual ~BooleanExpression() = default;

virtual bool evaluate(Context&) = 0;

virtual UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> replace(String&, BooleanExpression&) = 0;

virtual UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> copy() const = 0;

};

class VariableExpression;

class Context {

private:

TreeMap<const VariableExpression*, bool> m;

public:

Context() = default;

[[nodiscard]]

bool lookup(const VariableExpression* key) const {

return m.at(key);

}

void assign(VariableExpression* key, bool value) {

m[key] = value;

}

};

class VariableExpression : public BooleanExpression {

private:

String name;

public:

VariableExpression(const String& name):

name{name} {}

virtual ~VariableExpression() = default;

[[nodiscard]]

virtual bool evaluate(Context& context) const {

return context.lookup(this);

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual UniquePtr<VariableExpression> replace(const String& name, BooleanExpression& exp) {

if (this->name == name) {

return std::make_unique<VariableExpression>(exp.copy());

} else {

return std::make_unique<VariableExpression>(name);

}

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> copy() const {

return std::make_unique<BooleanExpression>(name);

}

VariableExpression(const VariableExpression&) = delete;

VariableExpression& operator=(const VariableExpression&) = delete;

};

class AndExpression : public BooleanExpression {

private:

UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> operand1;

UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> operand2;

public:

AndExpression(UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> op1, UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> op2):

operand1{std::move(op1)}, operand{std::move(op2)} {}

virtual ~AndExpression() = default;

[[nodiscard]]

virtual bool evaluate(Context& context) const {

return operand1->evaluate(context) && operand2->evaluate(context);

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> replace(const String& name, BooleanExpression& exp) const {

return std::make_unique<AndExpression>(

operand1->replace(name, exp),

operand2->replace(name, exp)

);

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> copy() const {

return std::make_unique<AndExpression>(operand1->copy(), operand2->copy());

}

AndExpression(const AndExpression&) = delete;

AndExpression& operator=(const AndExpression&) = delete;

};

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> expression;

Context context;

UniquePtr<VariableExpression> x = std::make_unique<VariableExpression>("X");

UniquePtr<VariableExpression> y = std::make_unique<VariableExpression>("Y");

UniquePtr<BooleanExpression> expression; = std::make_unique<AndExpression>(x, y);

context.assign(x.get(), false);

context.assign(y.get(), true);

bool result = expression->evaluate(context);

std::println("{}", result);

context.assign(x.get(), true);

context.assign(y.get(), true);

result = expression->evaluate(context);

std::println("{}", result);

return 0;

}

The program output is:

0

1

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gamma, Erich; Helm, Richard; Johnson, Ralph; Vlissides, John (1994). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-63361-2.

- ^ Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, John Vlissides (1994). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison Wesley. pp. 243ff. ISBN 0-201-63361-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Interpreter design pattern - Problem, Solution, and Applicability". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

- ^ "The Interpreter design pattern - Structure and Collaboration". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-12.

External links

[edit]Interpreter pattern

View on Grokipediainterpret method that takes a context (e.g., input string or variables); TerminalExpression concrete classes for primitive elements like literals or variables; and NonterminalExpression classes for composite rules, such as operators, which recursively invoke interpret on child expressions.[3] A Context object often holds global information, like variable values or the input stream, to support evaluation.[2] This setup leverages a parse tree—typically built using the Composite pattern—to represent the sentence, allowing the interpreter to traverse and compute results bottom-up.[2][4]

The pattern's applicability is limited to simple languages due to the exponential complexity of parsing more intricate grammars; for complex cases, dedicated parser generators like ANTLR or Yacc are preferred over manual implementation.[2] Consequences include easier extension of the grammar by adding new expression types and support for multiple interpretations via the Visitor pattern, but it can lead to large class hierarchies and inefficient performance for deep recursion without optimizations like flyweight sharing for common subexpressions.[2] Known uses include SQL parsing engines, rule-based systems for boolean queries (e.g., evaluating "John is male" against a context of attributes), and recursive operations on tree-structured data like binary expression trees for summation.[3][4] It relates closely to the Composite pattern for building parse trees and the Flyweight pattern for efficiency in repeated substructures.[2]

Overview

Intent and Motivation

The Interpreter pattern is a behavioral design pattern that specifies how to evaluate sentences in a formal language by defining a representation for its grammar along with an interpreter that uses this representation to interpret the sentences.[5] It maps a domain to a language, the language to a grammar, and the grammar to a hierarchical object-oriented design, enabling the evaluation of expressions in that language.[5] The pattern's motivation arises from the need to parse and interpret simple languages, such as mathematical expressions or configuration rules, where ad-hoc string processing or custom parsing code becomes inefficient and hard to maintain as the language evolves.[6] In scenarios involving repeated problems within a well-defined domain, characterizing the domain as a "little language" allows for an interpretation engine to solve these issues more elegantly than bespoke solutions.[5] This approach originated in the context of object-oriented design for handling formal grammars without requiring full compiler development.[7] The core goal of the Interpreter pattern is to represent the rules of the language grammar as an abstract syntax tree (AST), which is then traversed recursively through a class hierarchy to evaluate expressions.[6] This structure facilitates the interpretation of valid sentences in the language by composing terminal and non-terminal expressions into a tree that mirrors the grammar's production rules.[5]Applicability and Problems Solved

The Interpreter pattern finds applicability in situations where a simple language must be interpreted, and its statements can be effectively represented as abstract syntax trees (ASTs). This approach is particularly useful for defining a grammatical representation of a domain-specific language (DSL) and providing an interpreter to evaluate sentences within it, enabling the processing of structured inputs like expressions or rules without bespoke procedural logic.[8] It solves key problems associated with interpreting such languages without a systematic structure, including code duplication arising from handling similar parsing rules in an ad-hoc manner and challenges in maintaining and extending the grammar as requirements evolve. For example, in scenarios involving nested expressions in query processors or script evaluators, traditional if-then-else chains or switch statements often lead to repetitive implementations for each rule variant, complicating scalability and introducing maintenance overhead.[5] The pattern is ideal when the grammar remains straightforward—typically involving a limited set of rules—and is unlikely to undergo frequent modifications, as increasingly complex grammars result in bloated class hierarchies that become difficult to manage. In such cases, alternatives like parser generators are preferable to avoid these proliferation issues.[8] Additionally, it should be employed only when runtime efficiency is not paramount, since direct AST traversal can incur performance costs compared to compiled or optimized representations, such as state machines for regular expressions.[9]Structure and Components

Key Participants

The Interpreter pattern defines a set of classes that collaboratively interpret sentences in a language, structured around an abstract syntax tree (AST) composed of expression nodes. Each participant plays a distinct role in building, representing, and evaluating these expressions according to a formal grammar. AbstractExpression declares an abstractInterpret() operation common to all nodes in the AST, providing a uniform interface for interpreting any expression regardless of its complexity. This abstraction enables polymorphic treatment of both simple and composite expressions during traversal and evaluation.

TerminalExpression implements the Interpret() operation for terminal symbols in the grammar, such as numeric literals or primitive operations that form the leaves of the AST. It performs interpretation directly on the provided context without recursing into child expressions, serving as the foundational elements that cannot be further decomposed.

NonterminalExpression represents nonterminal symbols by maintaining references to an aggregate of child expressions—either TerminalExpressions or other NonterminalExpressions—and implements Interpret() by recursively calling the operation on each child, then combining their results in accordance with the specific grammar rule it embodies. This recursive structure allows the pattern to handle hierarchical language constructs efficiently.

Context encapsulates global information pertinent to the interpretation, including the input to be parsed (e.g., a string or stream), variable bindings, or accumulated results, which is passed to expression nodes to inform their behavior without tight coupling between interpreters.

Client assembles the AST by instantiating and linking TerminalExpressions and NonterminalExpressions to match the target sentence's structure, initializes the Context with relevant data, and triggers interpretation by invoking Interpret() on the tree's root node. This participant orchestrates the overall process but remains decoupled from the specifics of individual expression evaluations.

UML Diagrams

The UML class diagram for the Interpreter pattern illustrates the structural hierarchy and relationships among its core participants, providing a visual blueprint for implementing a grammar interpreter. At the top, an abstract class or interface named AbstractExpression serves as the base, declaring a single abstract operationinterpret(Context context) that defines the common interface for interpreting expressions. Two concrete subclasses inherit from AbstractExpression: TerminalExpression, which implements interpret() to handle leaf nodes (simple symbols or values in the grammar without further decomposition), and NonterminalExpression, which also implements interpret() but recursively invokes the method on its child expressions to process composite rules. Additionally, a Context class is depicted, typically as a simple entity holding global information such as input data or state shared across interpretations, with the interpret() operations depending on it.[10][11]

The diagram emphasizes inheritance through generalization arrows from TerminalExpression and NonterminalExpression to AbstractExpression, ensuring polymorphic behavior. A key association is the composition relationship within NonterminalExpression, shown as a 1-to-many link to AbstractExpression (often via an attribute like List<AbstractExpression> expressions), allowing nonterminal nodes to aggregate multiple sub-expressions into a syntax tree. The Client (not always explicitly diagrammed but implied) interacts with Context and the root AbstractExpression, building and traversing the tree. This structure aligns with the pattern's goal of representing a language grammar as a class hierarchy, where terminal classes map to atomic rules and nonterminal classes to production rules.[12][5]

An accompanying UML object diagram demonstrates runtime instantiation, exemplifying how the class structure forms a composite abstract syntax tree (AST) for a specific expression, such as "2 + 3 * 4". In this visualization, a root object of type NonterminalExpression (representing addition) links via composition to a terminal object TerminalExpression (value 2) on the left and another NonterminalExpression (representing multiplication) on the right. The multiplication node further composes two TerminalExpression objects (values 3 and 4), forming a binary tree that mirrors operator precedence. Each object instance shows attribute values (e.g., the expressions list populated with child references) and links back to a shared Context object containing the input string or evaluation state. This object diagram highlights the pattern's recursive composition at runtime, where interpretation traverses the tree depth-first to compute results like 14.[10][6]

Key relationships in these diagrams underscore the pattern's reliance on composition for building hierarchical structures: the 1-to-many aggregation in NonterminalExpression enables flexible tree construction without fixed arity, while the dependency from all expressions to Context ensures centralized state management during traversal, avoiding global variables. These notations conform to standard UML 2.0 conventions for behavioral patterns, facilitating clear communication of the design in object-oriented modeling tools.[12][5]

Implementation

Core Steps

The implementation of the Interpreter pattern follows a structured sequence of steps to define, represent, and evaluate expressions in a domain-specific language. This process ensures that the grammar is translated into an object-oriented structure suitable for recursive interpretation, leveraging an abstract syntax tree (AST) to process inputs systematically.[5][6] The first step is to define the grammar of the language, specifying its production rules, and map these rules to classes within the pattern's class hierarchy. Each nonterminal production rule corresponds to a subclass of an abstract NonterminalExpression, while terminal symbols are handled by TerminalExpression subclasses; this mapping creates a representation where the grammar's structure directly informs the object model.[5][13][14] Next, implement the interpret method recursively across the expression classes to traverse and evaluate the AST. This method, defined in an abstract Expression interface or superclass, takes a Context object to manage global state such as input data or intermediate results; nonterminal expressions invoke interpret on their child expressions, combining results according to the grammar rule, while terminal expressions perform base-level operations like retrieving literal values.[5][6][13] The third step occurs in the client code, where the AST is constructed based on the parsed input expression by instantiating and composing the appropriate TerminalExpression and NonterminalExpression objects into a tree structure, with the root node representing the overall expression. Once built, the client calls the interpret method on this root node, propagating evaluation down the tree via recursion to produce the final output.[5][6][13] Recursion is handled by distinguishing base cases in terminal expressions, which return concrete values without further calls, from nonterminal expressions that recursively delegate to sub-expressions before applying the rule's logic, ensuring the evaluation terminates for valid finite grammars.[5][14]Design Considerations

When applying the Interpreter pattern, performance is a primary concern, particularly for grammars involving recursive descent parsing, which can lead to exponential time complexity in large or deeply nested expressions due to repeated traversals of the expression tree.[15] To mitigate this, designers often integrate the Flyweight pattern to share common subexpressions across interpretations, reducing memory usage and computation by caching and reusing immutable terminal nodes rather than recreating them. Extensibility is one of the pattern's strengths, as new grammar rules can be added by subclassing the abstract expression class, allowing the interpreter to handle additional sentence structures without modifying existing code. However, this reliance on inheritance can result in a class explosion for moderately complex grammars, where each production rule requires a new subclass, leading to a bloated hierarchy that becomes difficult to maintain and extend further.[15] Error handling in the Interpreter pattern typically involves embedding validation logic within theinterpret method of expression classes to detect invalid inputs, such as malformed sentences or type mismatches, and propagating errors via exceptions or by updating flags in the shared context object to signal failures without halting the entire interpretation process.[16]

The pattern should be avoided for complex languages with ambiguous or large grammars, where manual class hierarchies become unwieldy; in such cases, parser generators like ANTLR are preferable, as they automate the creation of efficient lexers, parsers, and abstract syntax tree walkers from grammar specifications.

Examples

Simple Expression Evaluator

The Simple Expression Evaluator serves as an introductory implementation of the Interpreter pattern, focusing on a minimal language for arithmetic expressions limited to addition, such as "2 + 3". This example constructs an abstract syntax tree (AST) where leaf nodes represent numeric values and internal nodes represent the addition operator, enabling recursive evaluation to compute the result. By defining grammar rules as classes, the pattern allows straightforward extension for additional operators while maintaining a clear separation between parsing and interpretation. Central to this evaluator are two key expression types: terminal and non-terminal. The terminal expression, NumberExpression, encapsulates a literal numeric value and serves as the base case in the recursion. It implements an interpret method that simply returns the stored value, fulfilling the role of a primitive element in the grammar without further decomposition.abstract class Expression {

public abstract int interpret();

}

class NumberExpression extends Expression {

private final int number;

public NumberExpression(int number) {

this.number = number;

}

@Override

public int interpret() {

return number;

}

}

abstract class Expression {

public abstract int interpret();

}

class NumberExpression extends Expression {

private final int number;

public NumberExpression(int number) {

this.number = number;

}

@Override

public int interpret() {

return number;

}

}

class AdditionExpression extends Expression {

private final Expression left;

private final Expression right;

public AdditionExpression(Expression left, Expression right) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

@Override

public int interpret() {

return left.interpret() + right.interpret();

}

}

class AdditionExpression extends Expression {

private final Expression left;

private final Expression right;

public AdditionExpression(Expression left, Expression right) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

@Override

public int interpret() {

return left.interpret() + right.interpret();

}

}

new AdditionExpression(new NumberExpression(2), new NumberExpression(3)). Evaluation begins by calling interpret on the root node, triggering recursive traversal: the AdditionExpression computes the sum of its children's interpretations, ultimately yielding 5 for the example. This flow decouples the grammar representation from the evaluation logic, allowing the same tree to support multiple interpretations if extended.

Advanced Rule-Based Interpreter

In rule-based systems, the Interpreter pattern facilitates the evaluation of complex logical conditions derived from business rules, such as eligibility criteria expressed in a simple domain-specific language. For instance, a rule like "if age > 18 then eligible" can be parsed into an abstract syntax tree of boolean expressions, where each node represents a condition or operator, enabling dynamic interpretation without recompiling the application. This approach is particularly useful for configurable rule engines in domains like finance or compliance, where rules evolve frequently. The core structure revolves around an abstractBooleanExpression class or interface that defines an interpret(Context context) method returning a boolean value. Concrete subclasses include VariableExpression for handling context-dependent variables, such as comparing a user's age against a threshold. AndExpression and OrExpression serve as non-terminal expressions that compose multiple sub-expressions using logical conjunction and disjunction, respectively. The Context class typically implements a key-value store, like a Map<String, Object>, to provide runtime values for variables during evaluation.

A representative implementation in Java might define the expressions as follows:

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

// Abstract base for boolean expressions

abstract class BooleanExpression {

abstract boolean interpret(Context context);

}

// Handles variable comparisons, e.g., "age > 18"

class VariableExpression extends BooleanExpression {

private String variableName;

private int threshold;

private String operator; // e.g., ">", ">="

public VariableExpression(String variableName, int threshold, String operator) {

this.variableName = variableName;

this.threshold = threshold;

this.operator = operator;

}

@Override

boolean interpret(Context context) {

Object value = context.get(variableName);

if (value instanceof Integer) {

int intValue = (Integer) value;

return switch (operator) {

case ">" -> intValue > threshold;

case ">=" -> intValue >= threshold;

default -> false;

};

}

return false;

}

}

// Logical AND of two expressions

class AndExpression extends BooleanExpression {

private BooleanExpression left;

private BooleanExpression right;

public AndExpression(BooleanExpression left, BooleanExpression right) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

@Override

boolean interpret(Context context) {

return left.interpret(context) && right.interpret(context);

}

}

// Logical OR of two expressions (similar structure to AndExpression)

class OrExpression extends BooleanExpression {

private BooleanExpression left;

private BooleanExpression right;

public OrExpression(BooleanExpression left, BooleanExpression right) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

@Override

boolean interpret(Context context) {

return left.interpret(context) || right.interpret(context);

}

}

// Context holds variable values

class Context {

private Map<String, Object> values = new HashMap<>();

public void set(String key, Object value) {

values.put(key, value);

}

public Object get(String key) {

return values.get(key);

}

}

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

// Abstract base for boolean expressions

abstract class BooleanExpression {

abstract boolean interpret(Context context);

}

// Handles variable comparisons, e.g., "age > 18"

class VariableExpression extends BooleanExpression {

private String variableName;

private int threshold;

private String operator; // e.g., ">", ">="

public VariableExpression(String variableName, int threshold, String operator) {

this.variableName = variableName;

this.threshold = threshold;

this.operator = operator;

}

@Override

boolean interpret(Context context) {

Object value = context.get(variableName);

if (value instanceof Integer) {

int intValue = (Integer) value;

return switch (operator) {

case ">" -> intValue > threshold;

case ">=" -> intValue >= threshold;

default -> false;

};

}

return false;

}

}

// Logical AND of two expressions

class AndExpression extends BooleanExpression {

private BooleanExpression left;

private BooleanExpression right;

public AndExpression(BooleanExpression left, BooleanExpression right) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

@Override

boolean interpret(Context context) {

return left.interpret(context) && right.interpret(context);

}

}

// Logical OR of two expressions (similar structure to AndExpression)

class OrExpression extends BooleanExpression {

private BooleanExpression left;

private BooleanExpression right;

public OrExpression(BooleanExpression left, BooleanExpression right) {

this.left = left;

this.right = right;

}

@Override

boolean interpret(Context context) {

return left.interpret(context) || right.interpret(context);

}

}

// Context holds variable values

class Context {

private Map<String, Object> values = new HashMap<>();

public void set(String key, Object value) {

values.put(key, value);

}

public Object get(String key) {

return values.get(key);

}

}

// Build the expression tree

BooleanExpression ageExpr = new VariableExpression("age", 18, ">");

BooleanExpression incomeExpr = new VariableExpression("income", 50000, ">");

BooleanExpression rule = new AndExpression(ageExpr, incomeExpr);

// Set context values

Context context = new Context();

context.set("age", 20);

context.set("income", 60000);

// Evaluate

boolean isEligible = rule.interpret(context); // Returns true

// Build the expression tree

BooleanExpression ageExpr = new VariableExpression("age", 18, ">");

BooleanExpression incomeExpr = new VariableExpression("income", 50000, ">");

BooleanExpression rule = new AndExpression(ageExpr, incomeExpr);

// Set context values

Context context = new Context();

context.set("age", 20);

context.set("income", 60000);

// Evaluate

boolean isEligible = rule.interpret(context); // Returns true

VariableExpression query the context directly, while composite nodes like AndExpression invoke interpret on their children before applying the operator. For deeply nested conditions, recursion depth corresponds to the tree's height, potentially reaching several levels in complex rules, which underscores the pattern's scalability for hierarchical logic while risking stack overflow in extreme cases if not managed.