Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prototype pattern

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The prototype pattern is a creational design pattern in software development. It is used when the types of objects to create is determined by a prototypical instance, which is cloned to produce new objects. This pattern is used to avoid subclasses of an object creator in the client application, like the factory method pattern does, and to avoid the inherent cost of creating a new object in the standard way (e.g., using the 'new' keyword) when it is prohibitively expensive for a given application.

To implement the pattern, the client declares an abstract base class that specifies a pure virtual clone() method. Any class that needs a "polymorphic constructor" capability derives itself from the abstract base class, and implements the clone() operation.

The client, instead of writing code that invokes the "new" operator on a hard-coded class name, calls the clone() method on the prototype, calls a factory method with a parameter designating the particular concrete derived class desired, or invokes the clone() method through some mechanism provided by another design pattern.

The mitotic division of a cell — resulting in two identical cells — is an example of a prototype that plays an active role in copying itself and thus, demonstrates the Prototype pattern. When a cell splits, two cells of identical genotype result. In other words, the cell clones itself.[1]

Overview

[edit]The prototype design pattern is one of the 23 Gang of Four design patterns that describe how to solve recurring design problems to design flexible and reusable object-oriented software, that is, objects that are easier to implement, change, test, and reuse.[2]: 117

The prototype design pattern solves problems like:[3]

- How can objects be created so that the specific type of object can be determined at runtime?

- How can dynamically loaded classes be instantiated?

Creating objects directly within the class that requires (uses) the objects is inflexible because it commits the class to particular objects at compile-time and makes it impossible to specify which objects to create at run-time.

The prototype design pattern describes how to solve such problems:

- Define a

Prototypeobject that returns a copy of itself. - Create new objects by copying a

Prototypeobject.

This enables configuration of a class with different Prototype objects, which are copied to create new objects, and even more, Prototype objects can be added and removed at run-time.

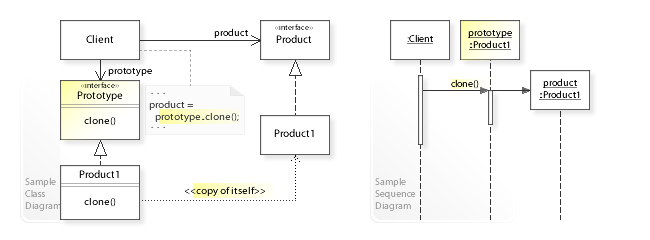

See also the UML class and sequence diagram below.

Structure

[edit]UML class and sequence diagram

[edit]

In the above UML class diagram,

the Client class refers to the Prototype interface for cloning a Product.

The Product1 class implements the Prototype interface by creating a copy of itself.

The UML sequence diagram shows the run-time interactions:

The Client object calls clone() on a prototype:Product1 object, which creates and returns a copy of itself (a product:Product1 object).

UML class diagram

[edit]

Rules of thumb

[edit]Sometimes creational patterns overlap—there are cases when either prototype or abstract factory would be appropriate. At other times, they complement each other: abstract factory might store a set of prototypes from which to clone and return product objects.[2]: 126 Abstract factory, builder, and prototype can use singleton in their implementations.[2]: 81, 134 Abstract factory classes are often implemented with factory methods (creation through inheritance), but they can be implemented using prototype (creation through delegation).[2]: 95

Often, designs start out using Factory Method (less complicated, more customizable, subclasses proliferate) and evolve toward abstract factory, prototype, or builder (more flexible, more complex) as the designer discovers where more flexibility is needed.[2]: 136

Prototype does not require subclassing, but it does require an "initialize" operation. Factory method requires subclassing, but does not require initialization.[2]: 116

Designs that make heavy use of the composite and decorator patterns often can benefit from Prototype as well.[2]: 126

A general guideline in programming suggests using the clone() method when creating a duplicate object during runtime to ensure it accurately reflects the original object. This process, known as object cloning, produces a new object with identical attributes to the one being cloned. Alternatively, instantiating a class using the new keyword generates an object with default attribute values.

For instance, in the context of designing a system for managing bank account transactions, it may be necessary to duplicate the object containing account information to conduct transactions while preserving the original data. In such scenarios, employing the clone() method is preferable over using new to instantiate a new object.

Example

[edit]C++23 Example

[edit]This C++23 implementation is based on the pre-C++98 implementation in the book. Discussion of the design pattern along with a complete illustrative example implementation using polymorphic class design are provided in the C++ Annotations.

import std;

using std::array;

using std::shared_ptr;

using std::unique_ptr;

using std::vector;

enum class Direction: char {

NORTH,

SOUTH,

EAST,

WEST

};

class MapSite {

public:

virtual void enter() = 0;

virtual unique_ptr<MapSite> clone() const = 0;

virtual ~MapSite() = default;

};

class Room: public MapSite {

private:

int roomNumber;

shared_ptr<array<shared_ptr<MapSite>, 4>> sides;

public:

explicit Room(int n = 0):

roomNumber{n}, sides{std::make_shared<array<shared_ptr<MapSite>, 4>>()} {}

~Room() = default;

Room& setSide(Direction d, shared_ptr<MapSite> ms) {

(*sides)[static_cast<size_t>(d)] = std::move(ms);

std::println("Room::setSide {} ms", d);

return *this;

}

virtual void enter() override {}

virtual unique_ptr<MapSite> clone() const override {

return std::make_unique<Room>(*this);

}

Room(const Room&) = delete;

Room& operator=(const Room&) = delete;

};

class Wall: public MapSite {

public:

Wall():

MapSite() {}

~Wall() = default;

virtual void enter() override {}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual unique_ptr<MapSite> clone() const override {

return std::make_unique<Wall>(*this);

}

};

class Door: public MapSite {

private:

shared_ptr<Room> room1;

shared_ptr<Room> room2;

public:

explicit Door(shared_ptr<Room> r1 = nullptr, shared_ptr<Room> r2 = nullptr):

MapSite(), room1{std::move(r1)}, room2{std::move(r2)} {}

~Door() = default;

virtual void enter() override {}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual unique_ptr<MapSite> clone() const override {

return std::make_unique<Door>(*this);

}

void initialize(shared_ptr<Room> r1, shared_ptr<Room> r2) {

room1 = std::move(r1);

room2 = std::move(r2);

}

Door(const Door&) = delete;

Door& operator=(const Door&) = delete;

};

class Maze {

private:

vector<shared_ptr<Room>> rooms;

public:

Maze() = default;

~Maze() = default;

Maze& addRoom(shared_ptr<Room> r) {

std::println("Maze::addRoom {}", reinterpret_cast<void*>(r.get()));

rooms.push_back(std::move(r));

return *this;

}

[[nodiscard]]

shared_ptr<Room> roomNo(int n) const {

for (const Room& r: rooms) {

// actual lookup logic here...

}

return nullptr;

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual unique_ptr<Maze> clone() const {

return std::make_unique<Maze>(*this);

}

};

class MazeFactory {

public:

MazeFactory() = default;

virtual ~MazeFactory() = default;

[[nodiscard]]

virtual unique_ptr<Maze> makeMaze() const {

return std::make_unique<Maze>();

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual shared_ptr<Wall> makeWall() const {

return std::make_shared<Wall>();

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual shared_ptr<Room> makeRoom(int n) const {

return std::make_shared<Room>(n);

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual shared_ptr<Door> makeDoor(shared_ptr<Room> r1, shared_ptr<Room> r2) const {

return std::make_shared<Door>(std::move(r1), std::move(r2));

}

};

class MazePrototypeFactory: public MazeFactory {

private:

unique_ptr<Maze> prototypeMaze;

shared_ptr<Room> prototypeRoom;

shared_ptr<Wall> prototypeWall;

shared_ptr<Door> prototypeDoor;

public:

MazePrototypeFactory(unique_ptr<Maze> m, shared_ptr<Wall> w, shared_ptr<Room> r, shared_ptr<Door> d):

MazeFactory(), prototypeMaze{std::move(m)}, prototypeRoom{std::move(r)},

prototypeWall{std::move(w)}, prototypeDoor{std::move(d)} {}

~MazePrototypeFactory() = default;

virtual unique_ptr<Maze> makeMaze() const override {

return prototypeMaze->clone();

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual shared_ptr<Room> makeRoom(int n) const override {

return prototypeRoom->clone();

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual shared_ptr<Wall> makeWall() const override {

return prototypeWall->clone();

}

[[nodiscard]]

virtual shared_ptr<Door> makeDoor(shared_ptr<Room> r1, shared_ptr<Room> r2) const override {

shared_ptr<Door> door = prototypeDoor->clone();

door->initialize(std::move(r1), std::move(r2));

return door;

}

MazePrototypeFactory(const MazePrototypeFactory&) = delete;

MazePrototypeFactory& operator=(const MazePrototypeFactory&) = delete;

};

class MazeGame {

public:

MazeGame() = default;

~MazeGame() = default;

[[nodiscard]]

unique_ptr<Maze> createMaze(MazePrototypeFactory& factory) {

unique_ptr<Maze> maze = factory.makeMaze();

shared_ptr<Room> r1 = factory.makeRoom(1);

shared_ptr<Room> r2 = factory.makeRoom(2);

shared_ptr<Door> door = factory.makeDoor(r1, r2);

maze->addRoom(std::move(r1))

.addRoom(std::move(r2));

r1->setSide(Direction::NORTH, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::EAST, door)

.setSide(Direction::SOUTH, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::WEST, factory.makeWall());

r2->setSide(Direction::NORTH, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::EAST, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::SOUTH, factory.makeWall())

.setSide(Direction::WEST, door);

return maze;

}

};

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

MazeGame game;

MazePrototypeFactory simpleMazeFactory(

std::make_unique<Maze>(),

std::make_shared<Wall>(),

std::make_shared<Room>(0),

std::make_shared<Door>()

);

unique_ptr<Maze> maze = game.createMaze(simpleMazeFactory);

}

The program output is:

Maze::addRoom 0x1160f50

Maze::addRoom 0x1160f70

Room::setSide 0 0x11613c0

Room::setSide 2 0x1160f90

Room::setSide 1 0x11613e0

Room::setSide 3 0x1161400

Room::setSide 0 0x1161420

Room::setSide 2 0x1161440

Room::setSide 1 0x1161460

Room::setSide 3 0x1160f90

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Duell, Michael (July 1997). "Non-Software Examples of Design Patterns". Object Magazine. 7 (5): 54. ISSN 1055-3614.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gamma, Erich; Helm, Richard; Johnson, Ralph; Vlissides, John (1994). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-63361-2.

- ^ "The Prototype design pattern - Problem, Solution, and Applicability". w3sDesign.com. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

Prototype pattern

View on Grokipediaclone operation, concrete prototype classes that implement this operation to produce shallow or deep copies of themselves, and a client that requests clones from the prototypes, often via a registry for managing multiple types.[1][2] Benefits include decoupling client code from specific classes, reducing code duplication for initialization, and simplifying the addition of new object types without altering existing hierarchies, though challenges arise with deep cloning of objects containing circular references or non-cloneable components.[2] In languages like Java, it is natively supported through the Cloneable interface and the Object.clone() method, facilitating widespread adoption in frameworks for UI elements, access controls, and data models.[2] The pattern often collaborates with other creational patterns like Abstract Factory or Factory Method to provide alternative instantiation strategies.[1]

Fundamentals

Definition

The Prototype pattern is a creational design pattern that enables the creation of new objects by cloning an existing prototypical instance, rather than invoking costly constructors or subclassing the creator class. Its intent is to specify the kinds of objects to create using a prototypical instance, and to create new objects by copying this prototype.[4] This approach promotes flexibility in object creation, allowing systems to produce instances without tightly coupling to specific classes, which is particularly useful in scenarios involving dynamic or variable object types. Introduced by the Gang of Four—Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides—in their seminal 1994 book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, the Prototype pattern is one of the 23 classic design patterns categorized under creational patterns.[4] The pattern's core principle revolves around leveraging an existing object as a template for replication, thereby avoiding the overhead of traditional instantiation processes and enabling the addition of new types through prototypes rather than extensive code modifications. At its foundation, the Prototype pattern comprises three basic components: a Prototype interface that declares a clone operation, one or more ConcretePrototype classes that implement the clone method to produce duplicates of themselves, and a Client that utilizes the prototype to request and customize new instances.[4] This structure supports object creation without prior knowledge of the exact class, fostering loose coupling and extensibility in object-oriented systems.Motivation and Use Cases

The Prototype pattern addresses the challenge of object creation in object-oriented systems where direct instantiation via constructors is inefficient or impractical, particularly when objects require extensive initialization, such as populating large datasets or performing resource-heavy computations. By allowing new objects to be produced through cloning an existing prototype instance, the pattern eliminates the need to repeatedly execute costly setup procedures or pass numerous parameters to constructors, thereby improving performance and simplifying the creation process.[5] This approach is especially valuable in environments demanding runtime flexibility, where the system must remain independent of specific concrete classes for instantiation, avoiding dependencies on class hierarchies or subclass proliferation that would otherwise occur when handling varied object configurations. For instance, it reduces coupling by delegating the cloning responsibility to the objects themselves through a common interface, enabling polymorphic behavior without exposing internal construction details.[6] Common use cases arise in domains like game development, where prototypes facilitate the efficient duplication of complex entities such as maze rooms or character models, each potentially loaded with graphical assets or behavioral rules, without rebuilding them from scratch each time. In graphical user interface (GUI) frameworks, the pattern supports creating variations of UI components, like menu items or shapes, by cloning base prototypes and applying minor customizations at runtime. Additionally, it proves useful in document management systems for replicating templates with embedded data structures, ensuring quick generation of similar reports or layouts while preserving the original's integrity.[7]Design and Structure

Class Relationships

The Prototype pattern involves a small set of key participants that define its static structure. The central participant is the Prototype, an abstract base class or interface that declares aclone() method, providing the interface for creating duplicates of objects without relying on their concrete classes.[5] Concrete implementations, known as ConcretePrototype, extend or implement the Prototype and provide the actual logic for cloning, often by copying the object's state to produce a new instance of the same type. The Client interacts with the pattern by holding a reference to a Prototype instance and invoking its clone() method to generate copies, allowing the client to remain decoupled from specific implementation details.[8]

Relationships among these classes emphasize inheritance and composition for flexibility. The ConcretePrototype inherits from or implements the Prototype, ensuring that cloning operations adhere to a common interface while handling type-specific duplication. The Client composes a reference to the Prototype (or an instance thereof), enabling it to request clones dynamically; the returned object is always a new ConcretePrototype instance matching the original's type, supporting polymorphic behavior. This structure avoids direct instantiation via constructors, promoting reuse through object duplication rather than class-based creation.[9]

Responsibilities are clearly distributed to maintain the pattern's integrity. The Prototype solely declares the cloning interface, leaving implementation details to subclasses. ConcretePrototypes bear the burden of executing the clone operation, which may include initializing the copy with default or customized state if needed. The Client focuses on configuration and utilization of clones, benefiting from abstraction without needing knowledge of concrete types, which enhances maintainability in systems with variable object requirements.[8]

A common variation introduces a PrototypeManager (or registry), which is not part of the core pattern but extends it for centralized control. This optional class maintains a collection of named prototypes, allowing clients to retrieve and clone them by key, such as through a map structure; it handles registration, lookup, and sometimes removal, reducing direct client-prototype coupling in complex scenarios.[5]

UML Diagrams

The UML class diagram for the Prototype pattern illustrates the static structure of the participating classes and their relationships, using standard UML notation such as interfaces, inheritance arrows, and association lines. At the core is the Prototype interface, which declares a single abstract operationclone() that returns an instance of Prototype, enabling polymorphic object creation without coupling to concrete classes. A ConcretePrototype class realizes this interface by implementing the clone() method, typically through a copy constructor or serialization mechanism that produces a duplicate of itself while preserving the return type covariance. The Client class is depicted with an association to the Prototype interface, indicating it holds a reference to a prototype instance and invokes clone() to create new objects, promoting loose coupling via abstraction. This diagram assumes an object-oriented context with support for interfaces and inheritance, where the inheritance relationship is shown as a solid line with a hollow triangle arrowhead from ConcretePrototype to Prototype.

The class diagram emphasizes key method signatures, such as the clone() operation's return type being the Prototype interface to allow subclasses to override and return their own types, facilitating extension without modifying client code. Optional elements, like a prototype manager for registering and retrieving instances by name, may appear as a separate class with a composition relationship to multiple ConcretePrototypes, but the core structure focuses on the inheritance and client-prototype association.

Complementing the class diagram, the UML sequence diagram captures the dynamic behavior during object creation, showing interactions among lifelines for Client, Prototype, and ConcretePrototype using activation bars, message arrows, and return arrows in standard UML notation. The flow begins with the Client instantiating an initial ConcretePrototype object, followed by the Client sending a clone() message to this prototype reference (typed as Prototype). The ConcretePrototype then self-referentially invokes its own clone() implementation, which constructs a new instance by copying state—often via a constructor that takes the original as a parameter—and returns the clone to the Client, who proceeds to use it independently. This highlights the polymorphic dispatch at runtime, where the concrete type determines the cloning logic without the Client knowing the specific class.

The sequence diagram underscores the runtime flow of self-referential cloning, demonstrating how the pattern avoids direct new invocations in the Client, instead leveraging the prototype's knowledge of its own structure for efficient duplication, all while maintaining encapsulation through the interface. These diagrams collectively provide a visual blueprint for implementing the pattern in languages supporting interfaces, such as Java or C++, where UML's standard symbols ensure portability across tools like PlantUML or Enterprise Architect.

Implementation Details

Cloning Mechanisms

The core operation in the Prototype pattern is the cloning process, which produces a new object instance by duplicating the state of an existing prototype. This is achieved through a dedicated method, commonly namedclone(), implemented in a shared interface or abstract base class that all prototypes adhere to. The method returns an object of the same concrete type as the invoking instance, supporting polymorphic cloning where clients interact solely with the abstract type without specifying concrete classes.[5][10]

Several general approaches facilitate cloning, tailored to language features or requirements. Language-built-in mechanisms, such as Java's Cloneable interface or .NET's ICloneable interface, provide a clone() or Clone() method that prototypes can implement to return a copy; for example, Java's default implementation performs a shallow duplication, while .NET's lacks specification on copy depth and Microsoft recommends against its use in public APIs due to resulting ambiguity.[11] In environments lacking such support, copy constructors serve as an alternative, where a constructor accepts an instance of its own class as input and initializes fields accordingly to create the duplicate. Serialization offers another technique, involving converting the prototype to a byte stream and reconstructing it via deserialization to yield a clone, which is particularly useful for achieving deep copies across different contexts but incurs runtime costs due to I/O operations.[5][7][12]

An optional prototype manager, or registry, enhances manageability by centralizing access to prototypes. This associative structure stores pre-configured prototypes keyed by identifiers like names or types, offering methods to register, retrieve, and clone them on demand. By encapsulating prototype knowledge, the registry minimizes client dependencies on concrete implementations, enabling scalable systems with multiple prototype variants.[10][5]

Error handling in cloning addresses challenges like circular references, where interconnected objects risk infinite loops during state traversal; mitigation involves tracking visited objects with sets or markers to break cycles. Immutable fields, being unmodifiable, allow clones to share references efficiently without duplication, reducing overhead while preserving consistency, though care must be taken to avoid unintended shared mutations if immutability assumptions fail. Cloning approaches generally distinguish between shallow and deep copies, with the former duplicating only top-level structures and the latter recursing into nested objects.[5][7]

Shallow vs. Deep Copying

In the Prototype pattern, cloning an object can be performed via a shallow copy or a deep copy, each with distinct behaviors regarding how object references are handled. A shallow copy creates a new object instance that duplicates the primitive fields of the original but copies only the references to non-primitive (object) fields, rather than the objects themselves. This means the original and the clone share the same mutable sub-objects, which can lead to unintended side effects; for instance, if the clone modifies a shared list, the change will also affect the original object's list.) In contrast, a deep copy recursively clones all nested objects, producing fully independent copies of the entire object graph, including primitives and all referenced objects. This ensures that modifications to the clone do not impact the original, making it safer for structures with mutable components but at the cost of higher resource consumption due to the additional cloning operations.[13] Implementation of shallow copying is typically straightforward, relying on language-provided mechanisms such as simple field assignment in constructors or default cloning methods like Java'sObject.clone(), which performs a bit-wise copy of fields without recursing into references. Deep copying, however, requires more involved approaches, including recursive traversal of the object graph to clone each referenced object (often by overriding cloning methods in subclasses), serialization followed by deserialization to recreate the entire structure, or employing design patterns like the Visitor to handle complex hierarchies without tight coupling.[14]

The choice between shallow and deep copying involves key trade-offs based on the application's needs. Shallow copies are preferred for performance-critical scenarios where referenced objects are immutable or unlikely to be modified post-cloning, as they avoid the overhead of recursive operations. Deep copies are essential for achieving true isolation in object graphs containing mutable sub-objects, though they risk pitfalls such as infinite recursion when encountering circular references, which must be managed through techniques like tracking visited objects during traversal.

Practical Examples

Example in Java

The Prototype pattern in Java leverages the language's built-in cloning mechanism by implementing theCloneable marker interface and overriding the Object.clone() method, which by default performs a shallow copy of the object.[15] This approach allows prototypes to be duplicated efficiently without invoking costly constructors.[16]

Consider a simple example using geometric shapes, where an abstract Shape class serves as the prototype base. The Shape class implements Cloneable and provides an abstract clone() method that returns a Shape instance, handling the CloneNotSupportedException required by Java's cloning API.

import java.lang.CloneNotSupportedException;

public abstract class Shape implements Cloneable {

protected String color;

protected int x, y;

public Shape() {}

public Shape(String color, int x, int y) {

this.color = color;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public abstract Shape clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException;

// Getters and setters

public String getColor() { return color; }

public void setColor(String color) { this.color = color; }

public int getX() { return x; }

public void setX(int x) { this.x = x; }

public int getY() { return y; }

public void setY(int y) { this.y = y; }

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Shape [color=" + color + ", x=" + x + ", y=" + y + "]";

}

}

import java.lang.CloneNotSupportedException;

public abstract class Shape implements Cloneable {

protected String color;

protected int x, y;

public Shape() {}

public Shape(String color, int x, int y) {

this.color = color;

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public abstract Shape clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException;

// Getters and setters

public String getColor() { return color; }

public void setColor(String color) { this.color = color; }

public int getX() { return x; }

public void setX(int x) { this.x = x; }

public int getY() { return y; }

public void setY(int y) { this.y = y; }

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Shape [color=" + color + ", x=" + x + ", y=" + y + "]";

}

}

Circle, extend Shape and override clone() to invoke super.clone() for a shallow copy, ensuring the new object shares the same primitive field values but references to any mutable objects would be shared unless handled otherwise.

public class Circle extends Shape {

private int radius;

public Circle() {}

public Circle(String color, int x, int y, int radius) {

super(color, x, y);

this.radius = radius;

}

@Override

public Shape clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException {

return (Shape) super.clone();

}

// Getter and setter

public int getRadius() { return radius; }

public void setRadius(int radius) { this.radius = radius; }

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Circle [color=" + color + ", x=" + x + ", y=" + y + ", radius=" + radius + "]";

}

}

public class Circle extends Shape {

private int radius;

public Circle() {}

public Circle(String color, int x, int y, int radius) {

super(color, x, y);

this.radius = radius;

}

@Override

public Shape clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException {

return (Shape) super.clone();

}

// Getter and setter

public int getRadius() { return radius; }

public void setRadius(int radius) { this.radius = radius; }

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Circle [color=" + color + ", x=" + x + ", y=" + y + ", radius=" + radius + "]";

}

}

Circle is instantiated once, then cloned multiple times, with post-clone modifications to properties like color and radius to demonstrate that the clones are independent objects. This avoids repeated constructor calls while allowing customization.

public class PrototypeDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) throws CloneNotSupportedException {

// Create prototype

Circle original = new Circle("red", 10, 20, 5);

System.out.println("Original: " + original);

// Clone and modify

Circle clone1 = (Circle) original.clone();

clone1.setColor("blue");

clone1.setRadius(10);

System.out.println("Clone 1: " + clone1);

Circle clone2 = (Circle) original.clone();

clone2.setX(30);

clone2.setY(40);

System.out.println("Clone 2: " + clone2);

// Verify independence

System.out.println("Original after clones: " + original);

System.out.println("Clones are distinct: " + (original != clone1 && original != clone2));

}

}

public class PrototypeDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) throws CloneNotSupportedException {

// Create prototype

Circle original = new Circle("red", 10, 20, 5);

System.out.println("Original: " + original);

// Clone and modify

Circle clone1 = (Circle) original.clone();

clone1.setColor("blue");

clone1.setRadius(10);

System.out.println("Clone 1: " + clone1);

Circle clone2 = (Circle) original.clone();

clone2.setX(30);

clone2.setY(40);

System.out.println("Clone 2: " + clone2);

// Verify independence

System.out.println("Original after clones: " + original);

System.out.println("Clones are distinct: " + (original != clone1 && original != clone2));

}

}

Original: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=red, x=10, y=20, radius=5]

Clone 1: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=blue, x=10, y=20, radius=10]

Clone 2: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=red, x=30, y=40, radius=5]

Original after clones: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=red, x=10, y=20, radius=5]

Clones are distinct: true

Original: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=red, x=10, y=20, radius=5]

Clone 1: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=blue, x=10, y=20, radius=10]

Clone 2: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=red, x=30, y=40, radius=5]

Original after clones: [Circle](/page/Circle) [color=red, x=10, y=20, radius=5]

Clones are distinct: true

super.clone() to create a bit-for-bit copy of the object's fields, resulting in a shallow copy suitable for classes with only primitive or immutable fields; for shapes containing mutable arrays or collections, a deep copy would be necessary to avoid shared references, as detailed in the Shallow vs. Deep Copying section.

Example in Python

In Python, the Prototype pattern benefits from the language's duck typing, where objects are treated based on their behavior rather than explicit type declarations, allowing any class with a suitableclone method to function as a prototype without needing formal interfaces.[17] This dynamic approach, combined with the built-in copy module, enables straightforward object duplication.[18] The module provides copy.copy() for shallow copies and copy.deepcopy() for deep copies, which recursively duplicate nested objects to avoid shared references in mutable structures like lists.[18]

A practical implementation often involves a base Prototype class that defines a clone method using deepcopy for comprehensive replication, especially when dealing with complex, nested data. Consider a Document class that manages pages as a list of mutable content sections (e.g., lists representing editable text blocks). This setup demonstrates how deep copying ensures independence between the original and clone, preventing unintended modifications to shared nested elements.

import copy

class [Prototype](/page/Prototype):

"""Base class for prototypes with cloning support."""

def clone(self):

return copy.deepcopy(self)

class [Document](/page/Document)([Prototype](/page/Prototype)):

"""Concrete prototype representing a document with nested pages."""

def __init__(self):

self.pages = [] # List of mutable page contents (e.g., lists)

def add_page(self, page_content):

"""Add a new page with mutable content."""

self.pages.append(page_content)

# Client code: Registering and using prototypes

prototypes = {} # [Dictionary](/page/Dictionary) to manage registered prototypes

# Register a basic document prototype

basic_doc = Document()

basic_doc.add_page(['Introduction', 'Chapter 1']) # Mutable list as page content

prototypes['basic_document'] = basic_doc

# Clone the prototype

cloned_doc = prototypes['basic_document'].clone()

# Modify the clone independently

cloned_doc.add_page(['Appendix', 'References'])

cloned_doc.pages[0].append('Updated Section') # Modify nested list in clone

# Demonstrate separation: Original unchanged

print("Original document pages:")

print(f"Number of pages: {len(basic_doc.pages)}")

print(f"First page content: {basic_doc.pages[0]}")

print("\nCloned document pages:")

print(f"Number of pages: {len(cloned_doc.pages)}")

print(f"First page content: {cloned_doc.pages[0]}")

import copy

class [Prototype](/page/Prototype):

"""Base class for prototypes with cloning support."""

def clone(self):

return copy.deepcopy(self)

class [Document](/page/Document)([Prototype](/page/Prototype)):

"""Concrete prototype representing a document with nested pages."""

def __init__(self):

self.pages = [] # List of mutable page contents (e.g., lists)

def add_page(self, page_content):

"""Add a new page with mutable content."""

self.pages.append(page_content)

# Client code: Registering and using prototypes

prototypes = {} # [Dictionary](/page/Dictionary) to manage registered prototypes

# Register a basic document prototype

basic_doc = Document()

basic_doc.add_page(['Introduction', 'Chapter 1']) # Mutable list as page content

prototypes['basic_document'] = basic_doc

# Clone the prototype

cloned_doc = prototypes['basic_document'].clone()

# Modify the clone independently

cloned_doc.add_page(['Appendix', 'References'])

cloned_doc.pages[0].append('Updated Section') # Modify nested list in clone

# Demonstrate separation: Original unchanged

print("Original document pages:")

print(f"Number of pages: {len(basic_doc.pages)}")

print(f"First page content: {basic_doc.pages[0]}")

print("\nCloned document pages:")

print(f"Number of pages: {len(cloned_doc.pages)}")

print(f"First page content: {cloned_doc.pages[0]}")

Original document pages:

Number of pages: 1

First page content: ['Introduction', 'Chapter 1']

Cloned document pages:

Number of pages: 2

First page content: ['Introduction', 'Chapter 1', 'Updated Section']

Original document pages:

Number of pages: 1

First page content: ['Introduction', 'Chapter 1']

Cloned document pages:

Number of pages: 2

First page content: ['Introduction', 'Chapter 1', 'Updated Section']

deepcopy here ensures that the nested lists in pages are fully replicated, allowing modifications to the clone's content without affecting the original prototype—a critical feature for handling mutable nested structures common in Python applications.[18] In contrast to more verbose implementations in languages like Java, which require explicit interfaces and manual cloning logic, Python's reliance on the copy module makes the pattern notably concise and integrated.[19] The dictionary-based registry further simplifies managing multiple prototypes, enabling efficient instantiation by cloning pre-configured instances as needed.[19]