Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coefficient of determination

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (September 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

In statistics, the coefficient of determination, denoted R2 or r2 and pronounced "R squared", is the proportion of the variation in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variable(s). It is a statistic used in the context of statistical models whose main purpose is either the prediction of future outcomes or the testing of hypotheses, on the basis of other related information. It provides a measure of how well observed outcomes are replicated by the model, based on the proportion of total variation of outcomes explained by the model.[1][2][3]

There are several definitions of R2 that are only sometimes equivalent. In simple linear regression (which includes an intercept), r2 is simply the square of the sample correlation coefficient (r), between the observed outcomes and the observed predictor values.[4] If additional regressors are included, R2 is the square of the coefficient of multiple correlation. In both such cases, the coefficient of determination normally ranges from 0 to 1.

There are cases where R2 can yield negative values. This can arise when the predictions that are being compared to the corresponding outcomes have not been derived from a model-fitting procedure using those data. Even if a model-fitting procedure has been used, R2 may still be negative, for example when linear regression is conducted without including an intercept,[5] or when a non-linear function is used to fit the data.[6] In cases where negative values arise, the mean of the data provides a better fit to the outcomes than do the fitted function values, according to this particular criterion.

The coefficient of determination can be more intuitively informative than MAE, MAPE, MSE, and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation, as the former can be expressed as a percentage, whereas the latter measures have arbitrary ranges. It also proved more robust for poor fits compared to SMAPE on certain test datasets.[7]

When evaluating the goodness-of-fit of simulated (Ypred) versus measured (Yobs) values, it is not appropriate to base this on the R2 of the linear regression (i.e., Yobs= m·Ypred + b).[citation needed] The R2 quantifies the degree of any linear correlation between Yobs and Ypred, while for the goodness-of-fit evaluation only one specific linear correlation should be taken into consideration: Yobs = 1·Ypred + 0 (i.e., the 1:1 line).[8][9]

Definitions

[edit]

The better the linear regression (on the right) fits the data in comparison to the simple average (on the left graph), the closer the value of R2 is to 1. The areas of the blue squares represent the squared residuals with respect to the linear regression. The areas of the red squares represent the squared residuals with respect to the average value.

A data set has n values marked y1, ..., yn (collectively known as yi or as a vector y = [y1, ..., yn]T), each associated with a fitted (or modeled, or predicted) value f1, ..., fn (known as fi, or sometimes ŷi, as a vector f).

Define the residuals as ei = yi − fi (forming a vector e).

If is the mean of the observed data: then the variability of the data set can be measured with two sums of squares formulas:

- The sum of squares of residuals, also called the residual sum of squares:

- The total sum of squares (proportional to the variance of the data):

The most general definition of the coefficient of determination is

In the best case, the modeled values exactly match the observed values, which results in and R2 = 1. A baseline model, which always predicts y, will have R2 = 0.

Relation to unexplained variance

[edit]In a general form, R2 can be seen to be related to the fraction of variance unexplained (FVU), since the second term compares the unexplained variance (variance of the model's errors) with the total variance (of the data):

As explained variance

[edit]A larger value of R2 implies a more successful regression model.[4]: 463 Suppose R2 = 0.49. This implies that 49% of the variability of the dependent variable in the data set has been accounted for, and the remaining 51% of the variability is still unaccounted for. For regression models, the regression sum of squares, also called the explained sum of squares, is defined as

In some cases, as in simple linear regression, the total sum of squares equals the sum of the two other sums of squares defined above:

See Partitioning in the general OLS model for a derivation of this result for one case where the relation holds. When this relation does hold, the above definition of R2 is equivalent to

where n is the number of observations (cases) on the variables.

In this form R2 is expressed as the ratio of the explained variance (variance of the model's predictions, which is SSreg / n) to the total variance (sample variance of the dependent variable, which is SStot / n).

This partition of the sum of squares holds for instance when the model values ƒi have been obtained by linear regression. A milder sufficient condition reads as follows: The model has the form

where the qi are arbitrary values that may or may not depend on i or on other free parameters (the common choice qi = xi is just one special case), and the coefficient estimates and are obtained by minimizing the residual sum of squares.

This set of conditions is an important one and it has a number of implications for the properties of the fitted residuals and the modelled values. In particular, under these conditions:

As squared correlation coefficient

[edit]In linear least squares multiple regression (with fitted intercept and slope), R2 equals the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient between the observed and modeled (predicted) data values of the dependent variable.

In a linear least squares regression with a single explanator (with fitted intercept and slope), this is also equal to the squared Pearson correlation coefficient between the dependent variable and explanatory variable .

It should not be confused with the correlation coefficient between two explanatory variables, defined as

where the covariance between two coefficient estimates, as well as their standard deviations, are obtained from the covariance matrix of the coefficient estimates, .

Under more general modeling conditions, where the predicted values might be generated from a model different from linear least squares regression, an R2 value can be calculated as the square of the correlation coefficient between the original and modeled data values. In this case, the value is not directly a measure of how good the modeled values are, but rather a measure of how good a predictor might be constructed from the modeled values (by creating a revised predictor of the form α + βƒi).[citation needed] According to Everitt,[10] this usage is specifically the definition of the term "coefficient of determination": the square of the correlation between two (general) variables.

Interpretation

[edit]R2 is a measure of the goodness of fit of a model.[11] In regression, the R2 coefficient of determination is a statistical measure of how well the regression predictions approximate the real data points. An R2 of 1 indicates that the regression predictions perfectly fit the data.

Values of R2 outside the range 0 to 1 occur when the model fits the data worse than the worst possible least-squares predictor (equivalent to a horizontal hyperplane at a height equal to the mean of the observed data). This occurs when a wrong model was chosen, or nonsensical constraints were applied by mistake. If equation 1 of Kvålseth[12] is used (this is the equation used most often), R2 can be less than zero. If equation 2 of Kvålseth is used, R2 can be greater than one.

In all instances where R2 is used, the predictors are calculated by ordinary least-squares regression: that is, by minimizing SSres. In this case, R2 increases as the number of variables in the model is increased (R2 is monotone increasing with the number of variables included—it will never decrease). This illustrates a drawback to one possible use of R2, where one might keep adding variables (kitchen sink regression) to increase the R2 value. For example, if one is trying to predict the sales of a model of car from the car's gas mileage, price, and engine power, one can include probably irrelevant factors such as the first letter of the model's name or the height of the lead engineer designing the car because the R2 will never decrease as variables are added and will likely experience an increase due to chance alone.

This leads to the alternative approach of looking at the adjusted R2. The explanation of this statistic is almost the same as R2 but it penalizes the statistic as extra variables are included in the model. For cases other than fitting by ordinary least squares, the R2 statistic can be calculated as above and may still be a useful measure. If fitting is by weighted least squares or generalized least squares, alternative versions of R2 can be calculated appropriate to those statistical frameworks, while the "raw" R2 may still be useful if it is more easily interpreted. Values for R2 can be calculated for any type of predictive model, which need not have a statistical basis.

In a multiple linear model

[edit]Consider a linear model with more than a single explanatory variable, of the form

where, for the ith case, is the response variable, are p regressors, and is a mean zero error term. The quantities are unknown coefficients, whose values are estimated by least squares. The coefficient of determination R2 is a measure of the global fit of the model. Specifically, R2 is an element of [0, 1] and represents the proportion of variability in Yi that may be attributed to some linear combination of the regressors (explanatory variables) in X.[13]

R2 is often interpreted as the proportion of response variation "explained" by the regressors in the model. Thus, R2 = 1 indicates that the fitted model explains all variability in , while R2 = 0 indicates no 'linear' relationship (for straight line regression, this means that the straight line model is a constant line (slope = 0, intercept = ) between the response variable and regressors). An interior value such as R2 = 0.7 may be interpreted as follows: "Seventy percent of the variance in the response variable can be explained by the explanatory variables. The remaining thirty percent can be attributed to unknown, lurking variables or inherent variability."

A caution that applies to R2, as to other statistical descriptions of correlation and association is that "correlation does not imply causation". In other words, while correlations may sometimes provide valuable clues in uncovering causal relationships among variables, a non-zero estimated correlation between two variables is not, on its own, evidence that changing the value of one variable would result in changes in the values of other variables. For example, the practice of carrying matches (or a lighter) is correlated with incidence of lung cancer, but carrying matches does not cause cancer (in the standard sense of "cause").

In case of a single regressor, fitted by least squares, R2 is the square of the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient relating the regressor and the response variable. More generally, R2 is the square of the correlation between the constructed predictor and the response variable. With more than one regressor, the R2 can be referred to as the coefficient of multiple determination.

Inflation of R2

[edit]In least squares regression using typical data, R2 is at least weakly increasing with an increase in number of regressors in the model. Because increases in the number of regressors increase the value of R2, R2 alone cannot be used as a meaningful comparison of models with very different numbers of independent variables. For a meaningful comparison between two models, an F-test can be performed on the residual sum of squares [citation needed], similar to the F-tests in Granger causality, though this is not always appropriate[further explanation needed]. As a reminder of this, some authors denote R2 by Rq2, where q is the number of columns in X (the number of explanators including the constant).

To demonstrate this property, first recall that the objective of least squares linear regression is

where Xi is a row vector of values of explanatory variables for case i and b is a column vector of coefficients of the respective elements of Xi.

The optimal value of the objective is weakly smaller as more explanatory variables are added and hence additional columns of (the explanatory data matrix whose ith row is Xi) are added, by the fact that less constrained minimization leads to an optimal cost which is weakly smaller than more constrained minimization does. Given the previous conclusion and noting that depends only on y, the non-decreasing property of R2 follows directly from the definition above.

The intuitive reason that using an additional explanatory variable cannot lower the R2 is this: Minimizing is equivalent to maximizing R2. When the extra variable is included, the data always have the option of giving it an estimated coefficient of zero, leaving the predicted values and the R2 unchanged. The only way that the optimization problem will give a non-zero coefficient is if doing so improves the R2.

The above gives an analytical explanation of the inflation of R2. Next, an example based on ordinary least square from a geometric perspective is shown below.[14]

A simple case to be considered first:

This equation describes the ordinary least squares regression model with one regressor. The prediction is shown as the red vector in the figure on the right. Geometrically, it is the projection of true value onto a model space in (without intercept). The residual is shown as the red line.

This equation corresponds to the ordinary least squares regression model with two regressors. The prediction is shown as the blue vector in the figure on the right. Geometrically, it is the projection of true value onto a larger model space in (without intercept). Noticeably, the values of and are not the same as in the equation for smaller model space as long as and are not zero vectors. Therefore, the equations are expected to yield different predictions (i.e., the blue vector is expected to be different from the red vector). The least squares regression criterion ensures that the residual is minimized. In the figure, the blue line representing the residual is orthogonal to the model space in , giving the minimal distance from the space.

The smaller model space is a subspace of the larger one, and thereby the residual of the smaller model is guaranteed to be larger. Comparing the red and blue lines in the figure, the blue line is orthogonal to the space, and any other line would be larger than the blue one. Considering the calculation for R2, a smaller value of will lead to a larger value of R2, meaning that adding regressors will result in inflation of R2.

Caveats

[edit]R2 does not indicate whether:

- the independent variables are a cause of the changes in the dependent variable;

- omitted-variable bias exists;

- the correct regression was used;

- the most appropriate set of independent variables has been chosen;

- there is collinearity present in the data on the explanatory variables;

- the model might be improved by using transformed versions of the existing set of independent variables;

- there are enough data points to make a solid conclusion;

- there are a few outliers in an otherwise good sample.

Extensions

[edit]Adjusted R2

[edit]The use of an adjusted R2 (one common notation is , pronounced "R bar squared"; another is or ) is an attempt to account for the phenomenon of the R2 automatically increasing when extra explanatory variables are added to the model. There are many different ways of adjusting.[15] By far the most used one, to the point that it is typically just referred to as adjusted R, is the correction proposed by Mordecai Ezekiel.[15][16][17] The adjusted R2 is defined as

where dfres is the degrees of freedom of the estimate of the population variance around the model, and dftot is the degrees of freedom of the estimate of the population variance around the mean. dfres is given in terms of the sample size n and the number of variables p in the model, dfres = n − p − 1. dftot is given in the same way, but with p being zero for the mean (i.e., dftot = n − 1).

Inserting the degrees of freedom and using the definition of R2, it can be rewritten as:

where p is the total number of explanatory variables in the model (excluding the intercept), and n is the sample size.

The adjusted R2 can be negative, and its value will always be less than or equal to that of R2. Unlike R2, the adjusted R2 increases only when the increase in R2 (due to the inclusion of a new explanatory variable) is more than one would expect to see by chance. If a set of explanatory variables with a predetermined hierarchy of importance are introduced into a regression one at a time, with the adjusted R2 computed each time, the level at which adjusted R2 reaches a maximum, and decreases afterward, would be the regression with the ideal combination of having the best fit without excess/unnecessary terms.

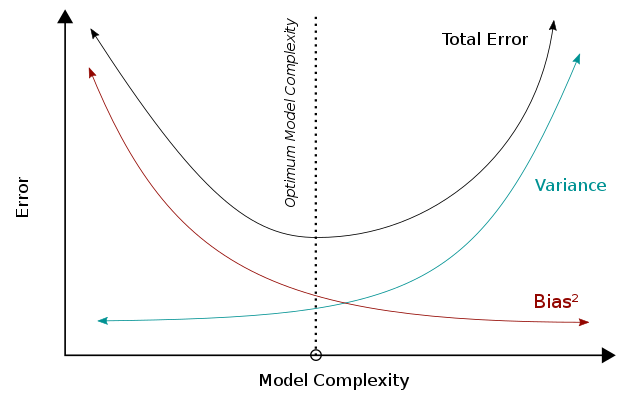

The adjusted R2 can be interpreted as an instance of the bias-variance tradeoff. When we consider the performance of a model, a lower error represents a better performance. When the model becomes more complex, the variance will increase whereas the square of bias will decrease, and these two metrics add up to be the total error. Combining these two trends, the bias-variance tradeoff describes a relationship between the performance of the model and its complexity, which is shown as a u-shape curve on the right. For the adjusted R2 specifically, the model complexity (i.e. number of parameters) affects the R2 and the term / frac and thereby captures their attributes in the overall performance of the model.

R2 can be interpreted as the variance of the model, which is influenced by the model complexity. A high R2 indicates a lower bias error because the model can better explain the change of Y with predictors. For this reason, we make fewer (erroneous) assumptions, and this results in a lower bias error. Meanwhile, to accommodate fewer assumptions, the model tends to be more complex. Based on bias-variance tradeoff, a higher complexity will lead to a decrease in bias and a better performance (below the optimal line). In R2, the term (1 − R2) will be lower with high complexity and resulting in a higher R2, consistently indicating a better performance.

On the other hand, the term/frac term is reversely affected by the model complexity. The term/frac will increase when adding regressors (i.e., increased model complexity) and lead to worse performance. Based on bias-variance tradeoff, a higher model complexity (beyond the optimal line) leads to increasing errors and a worse performance.

Considering the calculation of R2, more parameters will increase the R2 and lead to an increase in R2. Nevertheless, adding more parameters will increase the term/frac and thus decrease R2. These two trends construct a reverse u-shape relationship between model complexity and R2, which is in consistent with the u-shape trend of model complexity versus overall performance. Unlike R2, which will always increase when model complexity increases, R2 will increase only when the bias eliminated by the added regressor is greater than the variance introduced simultaneously. Using R2 instead of R2 could thereby prevent overfitting.

Following the same logic, adjusted R2 can be interpreted as a less biased estimator of the population R2, whereas the observed sample R2 is a positively biased estimate of the population value.[18] Adjusted R2 is more appropriate when evaluating model fit (the variance in the dependent variable accounted for by the independent variables) and in comparing alternative models in the feature selection stage of model building.[18]

The principle behind the adjusted R2 statistic can be seen by rewriting the ordinary R2 as

where and are the sample variances of the estimated residuals and the dependent variable respectively, which can be seen as biased estimates of the population variances of the errors and of the dependent variable. These estimates are replaced by statistically unbiased versions: and .

Despite using unbiased estimators for the population variances of the error and the dependent variable, adjusted R2 is not an unbiased estimator of the population R2,[18] which results by using the population variances of the errors and the dependent variable instead of estimating them. Ingram Olkin and John W. Pratt derived the minimum-variance unbiased estimator for the population R2,[19] which is known as Olkin–Pratt estimator. Comparisons of different approaches for adjusting R2 concluded that in most situations either an approximate version of the Olkin–Pratt estimator [18] or the exact Olkin–Pratt estimator [20] should be preferred over (Ezekiel) adjusted R2.

Coefficient of partial determination

[edit]The coefficient of partial determination can be defined as the proportion of variation that cannot be explained in a reduced model, but can be explained by the predictors specified in a full model.[21][22][23] This coefficient is used to provide insight into whether or not one or more additional predictors may be useful in a more fully specified regression model.

The calculation for the partial R2 is relatively straightforward after estimating two models and generating the ANOVA tables for them. The calculation for the partial R2 is

which is analogous to the usual coefficient of determination:

Generalizing and decomposing R2

[edit]As explained above, model selection heuristics such as the adjusted R2 criterion and the F-test examine whether the total R2 sufficiently increases to determine if a new regressor should be added to the model. If a regressor is added to the model that is highly correlated with other regressors which have already been included, then the total R2 will hardly increase, even if the new regressor is of relevance. As a result, the above-mentioned heuristics will ignore relevant regressors when cross-correlations are high.[24]

Alternatively, one can decompose a generalized version of R2 to quantify the relevance of deviating from a hypothesis.[24] As Hoornweg (2018) shows, several shrinkage estimators – such as Bayesian linear regression, ridge regression, and the (adaptive) lasso – make use of this decomposition of R2 when they gradually shrink parameters from the unrestricted OLS solutions towards the hypothesized values. Let us first define the linear regression model as

It is assumed that the matrix X is standardized with Z-scores and that the column vector is centered to have a mean of zero. Let the column vector refer to the hypothesized regression parameters and let the column vector denote the estimated parameters. We can then define

An R2 of 75% means that the in-sample accuracy improves by 75% if the data-optimized b solutions are used instead of the hypothesized values. In the special case that is a vector of zeros, we obtain the traditional R2 again.

The individual effect on R2 of deviating from a hypothesis can be computed with ('R-outer'). This times matrix is given by

where . The diagonal elements of exactly add up to R2. If regressors are uncorrelated and is a vector of zeros, then the diagonal element of simply corresponds to the r2 value between and . When regressors and are correlated, might increase at the cost of a decrease in . As a result, the diagonal elements of may be smaller than 0 and, in more exceptional cases, larger than 1. To deal with such uncertainties, several shrinkage estimators implicitly take a weighted average of the diagonal elements of to quantify the relevance of deviating from a hypothesized value.[24] Click on the lasso for an example.

R2 in logistic regression

[edit]In the case of logistic regression, usually fit by maximum likelihood, there are several choices of pseudo-R2.

One is the generalized R2 originally proposed by Cox & Snell,[25] and independently by Magee:[26]

where is the likelihood of the model with only the intercept, is the likelihood of the estimated model (i.e., the model with a given set of parameter estimates) and n is the sample size. It is easily rewritten to:

where D is the test statistic of the likelihood ratio test.

Nico Nagelkerke noted that it had the following properties:[27][22]

- It is consistent with the classical coefficient of determination when both can be computed;

- Its value is maximised by the maximum likelihood estimation of a model;

- It is asymptotically independent of the sample size;

- The interpretation is the proportion of the variation explained by the model;

- The values are between 0 and 1, with 0 denoting that model does not explain any variation and 1 denoting that it perfectly explains the observed variation;

- It does not have any unit.

However, in the case of a logistic model, where cannot be greater than 1, R2 is between 0 and : thus, Nagelkerke suggested the possibility to define a scaled R2 as R2/R2max.[22]

Comparison with residual statistics

[edit]Occasionally, residual statistics are used for indicating goodness of fit. The norm of residuals is calculated as the square-root of the sum of squares of residuals (SSR):

Similarly, the reduced chi-square is calculated as the SSR divided by the degrees of freedom.

Both R2 and the norm of residuals have their relative merits. For least squares analysis R2 varies between 0 and 1, with larger numbers indicating better fits and 1 representing a perfect fit. The norm of residuals varies from 0 to infinity with smaller numbers indicating better fits and zero indicating a perfect fit. One advantage and disadvantage of R2 is the term acts to normalize the value. If the yi values are all multiplied by a constant, the norm of residuals will also change by that constant but R2 will stay the same. As a basic example, for the linear least squares fit to the set of data:

x 1 2 3 4 5 y 1.9 3.7 5.8 8.0 9.6

R2 = 0.998, and norm of residuals = 0.302. If all values of y are multiplied by 1000 (for example, in an SI prefix change), then R2 remains the same, but norm of residuals = 302.

Another single-parameter indicator of fit is the RMSE of the residuals, or standard deviation of the residuals. This would have a value of 0.135 for the above example given that the fit was linear with an unforced intercept.[28]

History

[edit]The creation of the coefficient of determination has been attributed to the geneticist Sewall Wright and was first published in 1921.[29]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Steel, R. G. D.; Torrie, J. H. (1960). Principles and Procedures of Statistics with Special Reference to the Biological Sciences. McGraw Hill.

- ^ Glantz, Stanton A.; Slinker, B. K. (1990). Primer of Applied Regression and Analysis of Variance. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-023407-9.

- ^ Draper, N. R.; Smith, H. (1998). Applied Regression Analysis. Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-17082-2.

- ^ a b Devore, Jay L. (2011). Probability and Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. pp. 508–510. ISBN 978-0-538-73352-6.

- ^ Barten, Anton P. (1987). "The Coeffecient of Determination for Regression without a Constant Term". In Heijmans, Risto; Neudecker, Heinz (eds.). The Practice of Econometrics. Dordrecht: Kluwer. pp. 181–189. ISBN 90-247-3502-5.

- ^ Colin Cameron, A.; Windmeijer, Frank A.G. (1997). "An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models". Journal of Econometrics. 77 (2): 1790–2. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(96)01818-0.

- ^ Chicco, Davide; Warrens, Matthijs J.; Jurman, Giuseppe (2021). "The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation". PeerJ Computer Science. 7 (e623): e623. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.623. PMC 8279135. PMID 34307865.

- ^ Legates, D.R.; McCabe, G.J. (1999). "Evaluating the use of "goodness-of-fit" measures in hydrologic and hydroclimatic model validation". Water Resour. Res. 35 (1): 233–241. Bibcode:1999WRR....35..233L. doi:10.1029/1998WR900018. S2CID 128417849.

- ^ Ritter, A.; Muñoz-Carpena, R. (2013). "Performance evaluation of hydrological models: statistical significance for reducing subjectivity in goodness-of-fit assessments". Journal of Hydrology. 480 (1): 33–45. Bibcode:2013JHyd..480...33R. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.12.004.

- ^ Everitt, B. S. (2002). Cambridge Dictionary of Statistics (2nd ed.). CUP. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-521-81099-9.

- ^ Casella, Georges (2002). Statistical inference (Second ed.). Pacific Grove, Calif.: Duxbury/Thomson Learning. p. 556. ISBN 9788131503942.

- ^ Kvalseth, Tarald O. (1985). "Cautionary Note about R2". The American Statistician. 39 (4): 279–285. doi:10.2307/2683704. JSTOR 2683704.

- ^ "Linear Regression – MATLAB & Simulink". www.mathworks.com.

- ^ Faraway, Julian James (2005). Linear models with R (PDF). Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 9781584884255.

- ^ a b Raju, Nambury S.; Bilgic, Reyhan; Edwards, Jack E.; Fleer, Paul F. (1997). "Methodology review: Estimation of population validity and cross-validity, and the use of equal weights in prediction". Applied Psychological Measurement. 21 (4): 291–305. doi:10.1177/01466216970214001. ISSN 0146-6216. S2CID 122308344.

- ^ Mordecai Ezekiel (1930), Methods Of Correlation Analysis, Wiley, Wikidata Q120123877, pp. 208–211.

- ^ Yin, Ping; Fan, Xitao (January 2001). "Estimating R 2 Shrinkage in Multiple Regression: A Comparison of Different Analytical Methods" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Education. 69 (2): 203–224. doi:10.1080/00220970109600656. ISSN 0022-0973. S2CID 121614674.

- ^ a b c d Shieh, Gwowen (2008-04-01). "Improved shrinkage estimation of squared multiple correlation coefficient and squared cross-validity coefficient". Organizational Research Methods. 11 (2): 387–407. doi:10.1177/1094428106292901. ISSN 1094-4281. S2CID 55098407.

- ^ Olkin, Ingram; Pratt, John W. (March 1958). "Unbiased estimation of certain correlation coefficients". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 29 (1): 201–211. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177706717. ISSN 0003-4851.

- ^ Karch, Julian (2020-09-29). "Improving on Adjusted R-Squared". Collabra: Psychology. 6 (45). doi:10.1525/collabra.343. hdl:1887/3161248. ISSN 2474-7394.

- ^ Richard Anderson-Sprecher, "Model Comparisons and R2", The American Statistician, Volume 48, Issue 2, 1994, pp. 113–117.

- ^ a b c Nagelkerke, N. J. D. (September 1991). "A Note on a General Definition of the Coefficient of Determination" (PDF). Biometrika. 78 (3): 691–692. doi:10.1093/biomet/78.3.691. JSTOR 2337038.

- ^ "regression – R implementation of coefficient of partial determination". Cross Validated.

- ^ a b c Hoornweg, Victor (2018). "Part II: On Keeping Parameters Fixed". Science: Under Submission. Hoornweg Press. ISBN 978-90-829188-0-9.

- ^ Cox, D. D.; Snell, E. J. (1989). The Analysis of Binary Data (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall.

- ^ Magee, L. (1990). "R2 measures based on Wald and likelihood ratio joint significance tests". The American Statistician. 44 (3): 250–3. doi:10.1080/00031305.1990.10475731.

- ^ Nagelkerke, Nico J. D. (1992). Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Functional Relationships, Pays-Bas. Lecture Notes in Statistics. Vol. 69. ISBN 978-0-387-97721-8.

- ^ OriginLab webpage, http://www.originlab.com/doc/Origin-Help/LR-Algorithm. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Wright, Sewall (January 1921). "Correlation and causation". Journal of Agricultural Research. 20: 557–585.

Further reading

[edit]- Gujarati, Damodar N.; Porter, Dawn C. (2009). Basic Econometrics (Fifth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin. pp. 73–78. ISBN 978-0-07-337577-9.

- Hughes, Ann; Grawoig, Dennis (1971). Statistics: A Foundation for Analysis. Reading: Addison-Wesley. pp. 344–348. ISBN 0-201-03021-7.

- Kmenta, Jan (1986). Elements of Econometrics (Second ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 240–243. ISBN 978-0-02-365070-3.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S.; Skalaban, Andrew (1990). "The R-Squared: Some Straight Talk". Political Analysis. 2: 153–171. doi:10.1093/pan/2.1.153. JSTOR 23317769.

- Chicco, Davide; Warrens, Matthijs J.; Jurman, Giuseppe (2021). "The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation". PeerJ Computer Science. 7 (e623): e623. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.623. PMC 8279135. PMID 34307865.