Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

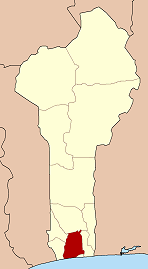

Allada

View on WikipediaAllada [a.la.da] is a town, arrondissement, and commune, located in the Atlantique Department of Benin.

Key Information

The current town of Allada corresponds to Great Ardra (also called Grand Ardra, or Arda), which was the capital of a Fon kingdom also called Allada (the kingdom of Ardra or kingdom of Allada), which existed as a sovereign kingdom from around the 13th or 14th century (date of the initial settlements by Aja people, reorganized as a kingdom c. 1600) until 1724, when it fell to the armies of neighbour Kingdom of Dahomey. The present-day commune of Allada covers an area of 381 square kilometres and as of 2013 had a population of 127,512 people.[1]

History

[edit]In the mid-sixteenth century, Allada (then called Grand Ardra, or Arda) had a population of about 30,000 people.[2]

The original inhabitants of Ardra were ethnic Aja.[3] According to oral tradition, the Aja migrated to southern Benin around the 12th or 13th century, coming from Tado, on the Mono River in modern Togo. They established themselves in the area that currently corresponds to southern Benin, until c. 1600, when three brothers – Kokpon, Do-Aklin, and Te-Agdanlin – split the rule of the region amongst themselves: Kokpon took the capital city of Great Ardra, reigning over the Allada kingdom, while his brother Do-Aklin founded Abomey (which would become capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey) and their brother Te-Agdanlin founded Little Ardra, also known as Ajatche(Little Adja), later called Porto Novo (literally, "New Port") by Portuguese traders (which is the current capital city of Benin).

Notable citizens and residents

[edit]The Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture, who was the grandson of the Allada prince Gaou Guinou, was the founding father of the Republic of Haiti.[4] There is a statue of L'Ouverture in the north of the town.[5]

Demographics

[edit]The main town demographics:

| Year | Population[6] |

|---|---|

| 1979 | 12 022 |

| 2008 (estimate) | 21 833 |

References

[edit]- ^ "Communes of Benin". Statoids. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Monroe, Cameron. "Urbanism on West Africa's Slave Coast". American Scientist. Archived from the original on 13 January 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Asiwaju, A. I. (1979). "The Aja-Speaking Peoples of Nigeria: A Note on Their Origins, Settlement and Cultural Adaptation up to 1945". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 49 (1): 15–28. doi:10.2307/1159502. ISSN 0001-9720. JSTOR 1159502. S2CID 145468899.

- ^ Beard, John R. (1863). Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography. Boston: James Redpath. p. 35. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Butler, Stuart (2019) Bradt Travel Guide - Benin, pgs. 100

- ^ "Allada". World Gazetteer. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

Further reading

[edit]- Saheed Aderinto, African kingdoms: an encyclopedia of empires and civilizations, 2017 Google docs preview

6°39′N 2°09′E / 6.650°N 2.150°E