Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Military

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a distinct military uniform. They may consist of one or more military branches such as an army, navy, air force, space force, marines, or coast guard. The main task of a military is usually defined as defence of their state and its interests against external armed threats.

In broad usage, the terms "armed forces" and "military" are often synonymous, although in technical usage a distinction is sometimes made in which a country's armed forces may include other paramilitary forces such as armed police.

Beyond warfare, the military may be employed in additional sanctioned and non-sanctioned functions within the state, including internal security threats, crowd control, promotion of political agendas, emergency services and reconstruction, protecting corporate economic interests, social ceremonies, and national honour guards.[1] A nation's military may function as a discrete social subculture, with dedicated infrastructure such as military housing, schools, utilities, logistics, hospitals, legal services, food production, finance, and banking services.

The profession of soldiering is older than recorded history.[2] Some images of classical antiquity portray the power and feats of military leaders. The Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC from the reign of Ramses II, features in bas-relief monuments. The first Emperor of a unified China, Qin Shi Huang, created the Terracotta Army to represent his military might.[3] The Ancient Romans wrote many treatises and writings on warfare, as well as many decorated triumphal arches and victory columns.

Etymology and definitions

[edit]

The first recorded use of the word "military" in English, spelled militarie, was in 1582.[4] It comes from the Latin militaris (from Latin miles 'soldier') through French, but is of uncertain etymology, one suggestion being derived from *mil-it- – going in a body or mass.[5][6]

As a noun phrase, "the military" usually refers generally to a country's armed forces, or sometimes, more specifically, to the senior officers who command them.[4][7] In general, it refers to the physicality of armed forces, their personnel, equipment, and the physical area which they occupy.

As an adjective, military originally referred only to soldiers and soldiering, but it broadened to apply to land forces in general, and anything to do with their profession.[4] The names of both the Royal Military Academy (1741) and United States Military Academy (1802) reflect this. However, at about the time of the Napoleonic Wars, military began to be used in reference to armed forces as a whole, such as "military service", "military intelligence", and "military history". As such, it now connotes any activity performed by armed force personnel.[4]

History

[edit]

Military history is often considered to be the history of all conflicts, not just the history of the state militaries. It differs somewhat from the history of war, with military history focusing on the people and institutions of war-making, while the history of war focuses on the evolution of war itself in the face of changing technology, governments, and geography.

Military history has a number of facets. One main facet is to learn from past accomplishments and mistakes, so as to more effectively wage war in the future. Another is to create a sense of military tradition, which is used to create cohesive military forces. Still, another is to learn to prevent wars more effectively. Human knowledge about the military is largely based on both recorded and oral history of military conflicts (war), their participating armies and navies and, more recently, air forces.[8]

Organization

[edit]

Personnel and units

[edit]Despite the growing importance of military technology, military activity depends above all on people. For example, in 2000 the British Army declared: "Man is still the first weapon of war."[9]

Rank and role

[edit]The military organization is characterized by a command hierarchy divided by military rank, with ranks normally grouped (in descending order of authority) as officers (e.g. colonel), non-commissioned officers (e.g. sergeant), and personnel at the lowest rank (e.g. private). While senior officers make strategic decisions, subordinated military personnel (soldiers, sailors, marines, or airmen) fulfil them. Although rank titles vary by military branch and country, the rank hierarchy is common to all state armed forces worldwide.

In addition to their rank, personnel occupy one of many trade roles, which are often grouped according to the nature of the role's military tasks on combat operations: combat roles (e.g. infantry), combat support roles (e.g. combat engineers), and combat service support roles (e.g. logistical support).

Recruitment

[edit]Personnel may be recruited or conscripted, depending on the system chosen by the state. Most military personnel are males; the minority proportion of female personnel varies internationally (approximately 3% in India,[10] 10% in the UK,[11] 13% in Sweden,[12] 16% in the US,[13] and 27% in South Africa[14]). While two-thirds of states now recruit or conscript only adults, as of 2017 50 states still relied partly on children under the age of 18 (usually aged 16 or 17) to staff their armed forces.[15]

Whereas recruits who join as officers tend to be upwardly-mobile,[16][17] most enlisted personnel have a childhood background of relative socio-economic deprivation.[18][19][20] For example, after the US suspended conscription in 1973, "the military disproportionately attracted African American men, men from lower-status socioeconomic backgrounds, men who had been in nonacademic high school programs, and men whose high school grades tended to be low".[16] However, a study released in 2020 on the socio-economic backgrounds of U.S. Armed Forces personnel suggests that they are at parity or slightly higher than the civilian population with respect to socio-economic indicators such as parental income, parental wealth and cognitive abilities. The study found that technological, tactical, operational and doctrinal changes have led to a change in the demand for personnel. Furthermore, the study suggests that the most disadvantaged socio-economic groups are less likely to meet the requirements of the modern U.S. military.[21]

Obligations

[edit]The obligations of military employment are many. Full-time military employment normally requires a minimum period of service of several years; between two and six years is typical of armed forces in Australia, the UK and the US, for example, depending on role, branch, and rank.[22][23][24] Some armed forces allow a short discharge window, normally during training, when recruits may leave the armed force as of right.[25] Alternatively, part-time military employment, known as reserve service, allows a recruit to maintain a civilian job while training under military discipline at weekends; he or she may be called out to deploy on operations to supplement the full-time personnel complement. After leaving the armed forces, recruits may remain liable for compulsory return to full-time military employment in order to train or deploy on operations.[25][24]

Military law introduces offences not recognized by civilian courts, such as absence without leave (AWOL), desertion, political acts, malingering, behaving disrespectfully, and disobedience (see, for example, offences against military law in the United Kingdom).[26] Penalties range from a summary reprimand to imprisonment for several years following a court martial.[26] Certain rights are also restricted or suspended, including the freedom of association (e.g. union organizing) and freedom of speech (speaking to the media).[26] Military personnel in some countries have a right of conscientious objection if they believe an order is immoral or unlawful, or cannot in good conscience carry it out.

Personnel may be posted to bases in their home country or overseas, according to operational need, and may be deployed from those bases on exercises or operations. During peacetime, when military personnel are generally stationed in garrisons or other permanent military facilities, they conduct administrative tasks, training and education activities, technology maintenance, and recruitment.

Training

[edit]

Initial training conditions recruits for the demands of military life, including preparedness to injure and kill other people, and to face mortal danger without fleeing. It is a physically and psychologically intensive process which resocializes recruits for the unique nature of military demands.[citation needed] For example:

- Individuality is suppressed (e.g. by shaving the head of new recruits, issuing uniforms, denying privacy, and prohibiting the use of first names);[27][28]

- Daily routine is tightly controlled (e.g. recruits must make their beds, polish boots, and stack their clothes in a certain way, and mistakes are punished);[29][28]

- Continuous stressors deplete psychological resistance to the demands of their instructors (e.g. depriving recruits of sleep, food, or shelter, shouting insults and giving orders intended to humiliate)[30][28][29]

- Frequent punishments serve to condition group conformity and discourage poor performance;[28]

- The disciplined drill instructor is presented as a role model of the ideal soldier.[31]

Intelligence

[edit]The next requirement comes as a fairly basic need for the military to identify possible threats it may be called upon to face. For this purpose, some of the commanding forces and other military, as well as often civilian personnel participate in identification of these threats. This is at once an organization, a system and a process collectively called military intelligence (MI). Areas of study in Military intelligence may include the operational environment, hostile, friendly and neutral forces, the civilian population in an area of combat operations, and other broader areas of interest.[32]

The difficulty in using military intelligence concepts and military intelligence methods is in the nature of the secrecy of the information they seek, and the clandestine nature that intelligence operatives work in obtaining what may be plans for a conflict escalation, initiation of combat, or an invasion.

An important part of the military intelligence role is the military analysis performed to assess military capability of potential future aggressors, and provide combat modelling that helps to understand factors on which comparison of forces can be made. This helps to quantify and qualify such statements as: "China and India maintain the largest armed forces in the World" or that "the U.S. Military is considered to be the world's strongest".[33]

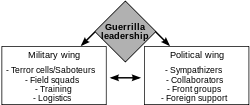

Although some groups engaged in combat, such as militants or resistance movements, refer to themselves using military terminology, notably 'Army' or 'Front', none have had the structure of a national military to justify the reference, and usually have had to rely on support of outside national militaries. They also use these terms to conceal from the MI their true capabilities, and to impress potential ideological recruits.

Having military intelligence representatives participate in the execution of the national defence policy is important, because it becomes the first respondent and commentator on the policy expected strategic goal, compared to the realities of identified threats. When the intelligence reporting is compared to the policy, it becomes possible for the national leadership to consider allocating resources over and above the officers and their subordinates military pay, and the expense of maintaining military facilities and military support services for them.

Budget

[edit]

|

|

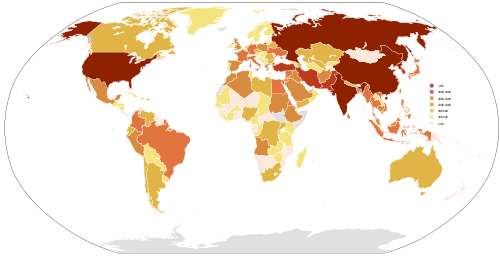

Defense economics is the financial and monetary efforts made to resource and sustain militaries, and to finance military operations, including war.

The process of allocating resources is conducted by determining a military budget, which is administered by a military finance organization within the military. Military procurement is then authorized to purchase or contract provision of goods and services to the military, whether in peacetime at a permanent base, or in a combat zone from local population.

-

History of military budgets by country

Capability development

[edit]Capability development, which is often referred to as the military 'strength', is arguably one of the most complex activities known to humanity; because it requires determining: strategic, operational, and tactical capability requirements to counter the identified threats; strategic, operational, and tactical doctrines by which the acquired capabilities will be used; identifying concepts, methods, and systems involved in executing the doctrines; creating design specifications for the manufacturers who would produce these in adequate quantity and quality for their use in combat; purchase the concepts, methods, and systems; create a forces structure that would use the concepts, methods, and systems most effectively and efficiently; integrate these concepts, methods, and systems into the force structure by providing military education, training, and practice that preferably resembles combat environment of intended use; create military logistics systems to allow continued and uninterrupted performance of military organizations under combat conditions, including provision of health services to the personnel, and maintenance for the equipment; the services to assist recovery of wounded personnel, and repair of damaged equipment; and finally, post-conflict demobilization, and disposal of war stocks surplus to peacetime requirements.

Development of military doctrine is perhaps the most important of all capability development activities, because it determines how military forces are used in conflicts, the concepts and methods used by the command to employ appropriately military skilled, armed and equipped personnel in achievement of the tangible goals and objectives of the war, campaign, battle, engagement, and action.[38] The line between strategy and tactics is not easily blurred, although deciding which is being discussed had sometimes been a matter of personal judgement by some commentators, and military historians. The use of forces at the level of organization between strategic and tactical is called operational mobility.

Science

[edit]

Because most of the concepts and methods used by the military, and many of its systems are not found in commercial branches, much of the material is researched, designed, developed, and offered for inclusion in arsenals by military science organizations within the overall structure of the military. Therefore, military scientists can be found interacting with all Arms and Services of the armed forces, and at all levels of the military hierarchy of command.

Although concerned with research into military psychology, particularly combat stress and how it affects troop morale, often the bulk of military science activities is directed at military intelligence technology, military communications, and improving military capability through research. The design, development, and prototyping of weapons, military support equipment, and military technology in general, is also an area in which much effort is invested – it includes everything from global communication networks and aircraft carriers to paint and food.

Logistics

[edit]

Possessing military capability is not sufficient if this capability cannot be deployed for, and employed in combat operations. To achieve this, military logistics are used for the logistics management and logistics planning of the forces military supply chain management, the consumables, and capital equipment of the troops.

Although mostly concerned with the military transport, as a means of delivery using different modes of transport; from military trucks, to container ships operating from permanent military base, it also involves creating field supply dumps at the rear of the combat zone, and even forward supply points in a specific unit's tactical area of responsibility.

These supply points are also used to provide military engineering services, such as the recovery of defective and derelict vehicles and weapons, maintenance of weapons in the field, the repair and field modification of weapons and equipment; and in peacetime, the life-extension programmes undertaken to allow continued use of equipment. One of the most important role of logistics is the supply of munitions as a primary type of consumable, their storage, and disposal.

In combat

[edit]The primary reason for the existence of the military is to engage in combat, should it be required to do so by the national defence policy, and to win. This represents an organisational goal of any military, and the primary focus for military thought through military history. How victory is achieved, and what shape it assumes, is studied by most, if not all, military groups on three levels.

Strategic victory

[edit]

Military strategy is the management of forces in wars and military campaigns by a commander-in-chief, employing large military forces, either national and allied as a whole, or the component elements of armies, navies and air forces; such as army groups, naval fleets, and large numbers of aircraft. Military strategy is a long-term projection of belligerents' policy, with a broad view of outcome implications, including outside the concerns of military command. Military strategy is more concerned with the supply of war and planning, than management of field forces and combat between them. The scope of strategic military planning can span weeks, but is more often months or even years.[38]

Operational victory

[edit]

Operational mobility is, within warfare and military doctrine, the level of command which coordinates the minute details of tactics with the overarching goals of strategy. A common synonym is operational art.

The operational level is at a scale bigger than one where line of sight and the time of day are important, and smaller than the strategic level, where production and politics are considerations. Formations are of the operational level if they are able to conduct operations on their own, and are of sufficient size to be directly handled or have a significant impact at the strategic level. This concept was pioneered by the German army prior to and during the Second World War. At this level, planning and duration of activities takes from one week to a month, and are executed by Field Armies and Army Corps and their naval and air equivalents.[38]

Tactical victory

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

Military tactics concerns itself with the methods for engaging and defeating the enemy in direct combat. Military tactics are usually used by units over hours or days, and are focused on the specific tasks and objectives of squadrons, companies, battalions, regiments, brigades, and divisions, and their naval and air force equivalents.[38]

One of the oldest military publications is The Art of War, by the Chinese philosopher Sun Tzu.[40] Written in the 6th century BCE, the 13-chapter book is intended as military instruction, and not as military theory, but has had a huge influence on Asian military doctrine, and from the late 19th century, on European and United States military planning. It has even been used to formulate business tactics, and can even be applied in social and political areas.

The Classical Greeks and the Romans wrote prolifically on military campaigning. Among the best-known Roman works are Julius Caesar's commentaries on the Gallic Wars, and the Roman Civil war – written about 50 BC.

Two major works on tactics come from the late Roman period: Taktike Theoria by Aelianus Tacticus, and De Re Militari ('On military matters') by Vegetius. Taktike Theoria examined Greek military tactics, and was most influential in the Byzantine world and during the Golden Age of Islam.

De Re Militari formed the basis of European military tactics until the late 17th century. Perhaps its most enduring maxim is Igitur qui desiderat pacem, praeparet bellum (let he who desires peace prepare for war).

Due to the changing nature of combat with the introduction of artillery in the European Middle Ages, and infantry firearms in the Renaissance, attempts were made to define and identify those strategies, grand tactics, and tactics that would produce a victory more often than that achieved by the Romans in praying to the gods before the battle.

Later this became known as military science, and later still, would adopt the scientific method approach to the conduct of military operations under the influence of the Industrial Revolution thinking. In his seminal book On War, the Prussian Major-General and leading expert on modern military strategy, Carl von Clausewitz defined military strategy as 'the employment of battles to gain the end of war'.[42] According to Clausewitz:

strategy forms the plan of the War, and to this end it links together the series of acts which are to lead to the final decision, that is to say, it makes the plans for the separate campaigns and regulates the combats to be fought in each.[43]

Hence, Clausewitz placed political aims above military goals, ensuring civilian control of the military. Military strategy was one of a triumvirate of 'arts' or 'sciences' that governed the conduct of warfare, the others being: military tactics, the execution of plans and manoeuvring of forces in battle, and maintenance of an army.

The meaning of military tactics has changed over time; from the deployment and manoeuvring of entire land armies on the fields of ancient battles, and galley fleets; to modern use of small unit ambushes, encirclements, bombardment attacks, frontal assaults, air assaults, hit-and-run tactics used mainly by guerrilla forces, and, in some cases, suicide attacks on land and at sea. Evolution of aerial warfare introduced its own air combat tactics. Often, military deception, in the form of military camouflage or misdirection using decoys, is used to confuse the enemy as a tactic.

A major development in infantry tactics came with the increased use of trench warfare in the 19th and 20th centuries. This was mainly employed in World War I in the Gallipoli campaign, and the Western Front. Trench warfare often turned to a stalemate, only broken by a large loss of life, because, in order to attack an enemy entrenchment, soldiers had to run through an exposed 'no man's land' under heavy fire from their opposing entrenched enemy.

Technology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2014) |

As with any occupation, since ancient times, the military has been distinguished from other members of the society by their tools: the weapons and military equipment used in combat. When Stone Age humans first took flint to tip the spear, it was the first example of applying technology to improve the weapon. Since then, the advances made by human societies, and that of weapons, has been closely linked. Stone weapons gave way to Bronze Age and Iron Age weapons such as swords and shields. With each technological change was realized some tangible increase in military capability, such as through greater effectiveness of a sharper edge in defeating armour, or improved density of materials used in manufacture of weapons.

On land, the first significant technological advance in warfare was the development of ranged weapons, notably the sling and later the bow and arrow. The next significant advance came with the domestication of the horses and mastering of equestrianism, creating cavalry and allowing for faster military advances and better logistics. Possibly the most significant advancement was the wheel, a staple of transportation, starting with the chariot and eventually siege engines. The bow was manufactured in increasingly larger and more powerful versions to increase both the weapon range and armour penetration performance, developing into composite bows, recurve bows, longbows, and crossbows. These proved particularly useful during the rise of cavalry, as horsemen encased in ever-more sophisticated armour came to dominate the battlefield.

In medieval China, gunpowder had been invented, and was increasingly used by the military in combat. The use of gunpowder in the early vase-like mortars in Europe, and advanced versions of the longbow and crossbow with armour-piercing arrowheads, put an end to the dominance of the armoured knight. Gunpowder resulted in the development and fielding of the musket, which could be used effectively with little training. In time, the successors to muskets and cannons, in the form of rifles and artillery, would become core battlefield technology.

As the speed of technological advances accelerated in civilian applications, so too did military and warfare become industrialized. The newly invented machine gun and repeating rifle redefined firepower on the battlefield, and, in part, explains the high casualty rates of the American Civil War and the decline of melee combat in warfare. The next breakthrough was the conversion of artillery parks from the muzzle-loading guns, to quicker breech-loading guns with recoiling barrels that allowed quicker aimed fire and use of a shield. The widespread introduction of low smoke (smokeless) propellant powders since the 1880s also allowed for a great improvement of artillery ranges. The development of breech loading had the greatest effect on naval warfare for the first time since the Middle Ages, altering the way weapons are mounted on warships. Naval tactics were divorced from the reliance on sails with the invention of the internal combustion. A further advance in military naval technology was the submarine and the torpedo.

During World War I, the need to break the deadlock of trench warfare saw the rapid development of many new technologies, particularly tanks. Military aviation was extensively used, and bombers became decisive in many battles of World War II, which marked the most frantic period of weapons development in history. Many new designs, and concepts were used in combat, and all existing technologies of warfare were improved between 1939 and 1945.

During World War II, significant advances were made in military communications through increased use of radio, military intelligence through use of the radar, and in military medicine through use of penicillin, while in the air, the guided missile, jet aircraft, and helicopters were seen for the first time. Perhaps the most infamous of all military technologies was the creation of nuclear weapons, although the exact effects of its radiation were unknown until the early 1950s. Far greater use of military vehicles had finally eliminated the cavalry from the military force structure. After World War II, with the onset of the Cold War, the constant technological development of new weapons was institutionalized, as participants engaged in a constant arms race in capability development. This constant state of weapons development continues into the present. Main battle tanks, and other heavy equipment such as armoured fighting vehicles, military aircraft, and ships, are characteristic to organized military forces.

The most significant technological developments that influenced combat have been guided missiles, which can be used by all branches of the armed services. More recently, information technology, and its use in surveillance, including space-based reconnaissance systems, have played an increasing role in military operations. The impact of information warfare, which focuses on attacking command communication systems, and military databases, has been coupled with the use of robotic systems in combat, such as unmanned combat aerial vehicles and unmanned ground vehicles.

Recently, there has also been a particular focus towards the use of renewable fuels for running military vehicles on. Unlike fossil fuels, renewable fuels can be produced in any country, creating a strategic advantage. The U.S. military has committed itself to have 50% of its energy consumption come from alternative sources.[44]

As part of society

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2014) |

For much of military history, the armed forces were considered to be for use by the heads of their societies, until recently, the crowned heads of states. In a democracy or other political system run in the public interest, it is a public force.

The relationship between the military and the society it serves is a complicated and ever-evolving one. Much depends on the nature of the society itself, and whether it sees the military as important, as for example in time of threat or war, or a burdensome expense typified by defence cuts in time of peace.

One difficult matter in the relation between military and society is control and transparency. In some countries, limited information on military operations and budgeting is accessible for the public. However, transparency in the military sector is crucial to fight corruption. This showed the Government Defence Anti-corruption Index Transparency International UK published in 2013.[45]

Militaries often function as societies within societies, by having their own military communities, economies, education, medicine, and other aspects of a functioning civilian society. A military is not limited to nations in of itself, as many private military companies (or PMCs) can be used or hired by organizations and figures as security, escort, or other means of protection where police, agencies, or militaries are absent or not trusted.

Ideology and ethics

[edit]

Militarist ideology is the society's social attitude of being best served, or being a beneficiary of a government, or guided by concepts embodied in the military culture, doctrine, system, or leaders.

Either because of the cultural memory, national history, or the potentiality of a military threat, the militarist argument asserts that a civilian population is dependent upon, and thereby subservient to the needs and goals of its military for continued independence. Militarism is sometimes contrasted with the concepts of comprehensive national power, soft power and hard power.

Most nations have separate military laws which regulate conduct in war and during peacetime. An early exponent was Hugo Grotius, whose On the Law of War and Peace (1625) had a major impact of the humanitarian approach to warfare development. His theme was echoed by Gustavus Adolphus.

Ethics of warfare have developed since 1945, to create constraints on the military treatment of prisoners and civilians, primarily by the Geneva Conventions; but rarely apply to use of the military forces as internal security troops during times of political conflict that results in popular protests and incitement to popular uprising.

International protocols restrict the use, or have even created international bans on some types of weapons, notably weapons of mass destruction (WMD). International conventions define what constitutes a war crime, and provides for war crimes prosecution. Individual countries also have elaborate codes of military justice, an example being the United States' Uniform Code of Military Justice that can lead to court martial for military personnel found guilty of war crimes.

Military actions are sometimes argued to be justified by furthering a humanitarian cause, such as disaster relief operations to defend refugees; such actions are called military humanism.

See also

[edit]- Arms industry

- Civil defense

- Civilian control of the military

- Command and control

- Conscription

- Deterrence theory

- Martial arts

- Martial law

- Mercenary

- Militaria

- Military academy

- Military advisor

- Military aid

- Military aid to the civil community (MACC)

- Military aid to the civil power (MACP)

- Military alliance

- Military dictatorship

- Military district

- Military engineering

- Military exercise

- Military fiat

- Military incompetence

- Military–industrial complex

- Military junta

- Military meteorology

- Military operations other than war

- Military police

- Military prison

- Military Revolution

- Military sociology

- Military terminology

- Militarization of police

- Militia

- Ministry of defence

- Mobilization

- Police

- Staff (military)

- Standing army

- Weapon

- Armed forces of the world

References

[edit]- ^ Jordan, David; Kiras, James D.; Lonsdale, David J.; Speller, Ian; Tuck, Christopher; Walton, C. Dale (2016). Understanding Modern Warfare (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1107134195.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2 September 2009). "War in Ancient Times". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ Terra cotta of massed ranks of Qin Shi Huang's terra cotta soldiers

- ^ a b c d "military". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 March 2019. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "military". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Tucker, T.G. (1985) Etymological dictionary of Latin, Ares publishers Inc., Chicago. p. 156

- ^ "Merriam Webster Dictionary online". Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Morillo, Stephen; Pavkovic, Michael F. (2006). What is Military History? (1 ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 2, 6–7. ISBN 0-7456-3390-0.

- ^ British Army (2000). "Soldiering: The military covenant" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Franz-Stefan Gady. "India's Military to Allow Women in Combat Roles". The Diplomat. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 2017". www.gov.uk. 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Försvarsmakten. "Historik". Försvarsmakten (in Swedish). Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ US Army (2013). "Support Army Recruiting". www.usarec.army.mil. Archived from the original on 9 November 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ Engelbrecht, Leon (29 June 2011). "Fact file: SANDF regular force levels by race & gender: April 30, 2011 | defenceWeb". www.defenceweb.co.za. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Where are child soldiers?". Child Soldiers International. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ a b Segal, D R; et al. (1998). "The all-volunteer force in the 1970s". Social Science Quarterly. 72 (2): 390–411. JSTOR 42863796.

- ^ Bachman, Jerald G.; Segal, David R.; Freedman-Doan, Peter; O'Malley, Patrick M. (2000). "Who chooses military service? Correlates of propensity and enlistment in the U.S. Armed Forces". Military Psychology. 12 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1207/s15327876mp1201_1. S2CID 143845150.

- ^ Brett, Rachel, and Irma Specht. Young Soldiers: Why They Choose to Fight. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2004. ISBN 1-58826-261-8[page needed]

- ^ "Machel Study 10-Year Strategic Review: Children and conflict in a changing world". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Iversen, Amy C.; Fear, Nicola T.; Simonoff, Emily; Hull, Lisa; Horn, Oded; Greenberg, Neil; Hotopf, Matthew; Rona, Roberto; Wessely, Simon (1 December 2007). "Influence of childhood adversity on health among male UK military personnel". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 191 (6): 506–511. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039818. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 18055954.

- ^ Asoni, Andrea; Gilli, Andrea; Gilli, Mauro; Sanandaji, Tino (30 January 2020). "A mercenary army of the poor? Technological change and the demographic composition of the post-9/11 U.S. military". Journal of Strategic Studies. 45 (4): 568–614. doi:10.1080/01402390.2019.1692660. ISSN 0140-2390. S2CID 213899510.

- ^ "Army – Artillery – Air Defender". army.defencejobs.gov.au. Retrieved 9 December 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Gee, David; Taylor, Rachel (1 November 2016). "Is it Counterproductive to Enlist Minors into the Army?". The RUSI Journal. 161 (6): 36–48. doi:10.1080/03071847.2016.1265837. ISSN 0307-1847. S2CID 157986637.

- ^ a b "What is a Military Enlistment Contract?". Findlaw. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ a b "The Army Terms of Service Regulations 2007". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ a b c UK, Ministry of Defence (2017). "Queen's Regulations for the Army (1975, as amended)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ McGurk, Dennis; et al. (2006). "Joining the ranks: The role of indoctrination in transforming civilians to service members". Military life: The psychology of serving in peace and combat. Vol. 2. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Security International. pp. 13–31. ISBN 978-0-275-98302-4.

- ^ a b c d Hockey, John (1986). Squaddies : portrait of a subculture. Exeter, Devon: University of Exeter. ISBN 978-0-85989-248-3. OCLC 25283124.

- ^ a b Bourne, Peter G. (1 May 1967). "Some Observations on the Psychosocial Phenomena Seen in Basic Training". Psychiatry. 30 (2): 187–196. doi:10.1080/00332747.1967.11023507. ISSN 0033-2747. PMID 27791700.

- ^ Grossman, Dave (2009). On killing : the psychological cost of learning to kill in war and society (Rev. ed.). New York: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 978-0-316-04093-8. OCLC 427757599.

- ^ Faris, John H. (16 September 2016). "The Impact of Basic Combat Training: The Role of the Drill Sergeant in the All-Volunteer Army". Armed Forces & Society. 2 (1): 115–127. doi:10.1177/0095327x7500200108. S2CID 145213941.

- ^ "University Catalog 2011/2012, Master Courses: pp.99, size: 17MB" (PDF). US National Intelligence University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ^ Statistics on Americans' opinion about the U.S. being the world's no1 military power Archived 10 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Gallup, March 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

- ^ "SIPRI Military Expenditure Database". SIPRI. 28 April 2025. Retrieved 28 April 2025.

- ^ Robertson, Peter. "Military PPP Data". Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ Robertson, Peter (20 September 2021). "The Real Military Balance: International Comparisons of Defense Spending". Review of Income and Wealth. 68 (3). Wiley: 797–818. doi:10.1111/roiw.12536.

- ^ 2017 data from: "Military expenditure (% of GDP). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Yearbook: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security". World Bank. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Dupuy, T.N. (1990) Understanding war: History and Theory of combat, Leo Cooper, London, p. 67

- ^ "Ukraine Deploys Anti-Drone Jamming Guns to its Forces on the Donbas Frontline". Defense Express. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "The Art of War". Mypivots.com. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ "Welcome to the Department of History". westpoint.edu. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ MacHenry, Robert (1993). "The New Encyclopædia Britannica". Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc: 305. Bibcode:1991neb..book.....G.

- ^ On War by General Carl von Clausewitz. 26 February 2006. Retrieved 31 May 2007 – via Gutenberg.org.

- ^ Craig Hooper. "Ray Mabus greening the military". NextNavy.com. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ Pyman, Mark (5 March 2013). "Transparency is feasible". www.DandC.eu. D+C Development and Cooperation, Engagement GlobalGmbH. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

Notes

[edit]External links

[edit]- Military Expenditure % of GDP hosted by Lebanese economy forum, extracted from the World Bank public data.

Military

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Scope

Etymology

The English adjective and noun "military," denoting matters or personnel related to soldiers and war, entered the language in the mid-15th century from Middle English militari, borrowed via Old French militaire.[10] This traces directly to Latin mīlitāris, an adjective meaning "of soldiers or war, warlike, or pertaining to military service," formed from mīles (genitive militis), the classical Latin term for "soldier," particularly a foot soldier in the Roman legions.[11] In Roman usage, mīles contrasted with higher-status cavalry or officers, emphasizing the common infantryman who served for pay (stipendium) and underwent rigorous training.[10] The etymology of mīles itself remains uncertain, with no definitive Indo-European root established despite scholarly proposals linking it to concepts of "milling" (as in grinding grain, metaphorically for organized masses) or "going with full force" via a reconstructed form like *mil-it-.[10] Early attestations appear in Latin texts from the 6th century BCE onward, predating Greek influences, and it lacks clear cognates in other Italic languages, suggesting possible pre-Indo-European substrate origins in the Italian peninsula.[12] Related derivatives in Latin include militia ("military service") and militare ("to serve as a soldier"), which influenced Romance languages and, through Norman French, much of modern European military terminology.[10]Core Concepts and Distinctions

The military refers to the organized armed forces of a state, structured to conduct warfare, defend territory, and achieve national security objectives through the application of combat power.[13] Core concepts include military doctrine, which encompasses fundamental principles guiding the employment of forces, providing a framework for operations rather than rigid rules. Operational concepts further translate military strength into power via schemes of maneuver for planning and execution. A primary distinction lies between regular military forces and paramilitary organizations. Regular militaries are professional entities under direct state control, equipped for external defense and large-scale combat, whereas paramilitaries operate in a military-like manner but lack full official status, often focusing on internal security, border patrol, or supplementary roles with semi-official sanction.[14] This separation ensures militaries prioritize existential threats while paramilitaries handle lower-intensity domestic functions, though overlaps can blur lines in unstable regimes. Forces may be professional volunteer armies or conscript-based. Professional armies consist of full-time volunteers with extended training, fostering expertise, cohesion, and adaptability, which empirical outcomes in conflicts like the post-1973 U.S. all-volunteer force demonstrate through sustained operational effectiveness.[15] Conscript armies, relying on mandatory short-term service, generate larger reserves at lower cost but suffer from reduced proficiency and motivation, as shorter tenures limit skill development and combat readiness.[16] Conventional warfare involves symmetric engagements between state militaries using uniformed troops, massed conventional arms, and structured battles for territorial control, as seen in World War II fronts.[17] In contrast, unconventional or irregular warfare employs asymmetric tactics by non-state actors or insurgents, leveraging guerrilla methods, subversion, and indirect approaches to erode adversary will without direct confrontation.[18] Militaries are typically divided into branches by operational domain: army for land operations, navy for maritime power projection, air force for aerial dominance, marine corps for amphibious assault, space force for orbital assets, and coast guard for coastal enforcement, each with specialized equipment, training, and doctrines to integrate in joint operations.[19] These distinctions enable comprehensive force employment across environments, from terrestrial battles to cyber and space domains.Evolution of Military Roles

In prehistoric societies, military roles primarily involved small-scale raids and defense of kin groups against resource competitors, with participants serving as ad hoc warriors drawn from the general population rather than specialized forces. Organized military structures emerged with early civilizations around 3150 BC, as evidenced by conflicts between Upper and Lower Egypt and Sumerian engagements with Elam, where forces focused on conquest, territorial control, and resource acquisition using rudimentary infantry formations.[20][21] The formation of empires in the Bronze Age shifted roles toward sustained campaigns of expansion and internal pacification, with ancient powers like Egypt under Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) deploying specialized infantry, chariots, and archers for offensive dominance and defensive consolidation.[22] In classical antiquity, professional armies such as Rome's legions, established by the 3rd century BC, expanded functions to include engineering (e.g., road and fort construction), provincial policing, and supply line maintenance alongside combat, enabling the maintenance of vast territories through disciplined, full-time service.[23] Medieval Europe transitioned to feudal systems by the 9th century, where military roles devolved to vassal levies and knightly retinues obligated for limited service in defense against invasions or feudal disputes, supplemented by mercenaries for offensive ventures like the Crusades (1095–1291), reflecting decentralized authority and seasonal mobilization rather than permanent forces.[24] The Ottoman Empire pioneered modern standing armies with the Janissaries in the 14th century, trained as elite infantry for conquest and imperial defense, while Europe lagged until France's 1445 Ordinance created the first permanent cavalry and infantry units, marking a shift to professional, state-controlled forces for continuous readiness and fiscal sustainability.[25] The 17th–19th centuries saw the proliferation of national standing armies across Europe, driven by gunpowder tactics and absolutist states, with roles encompassing not only interstate warfare but also internal suppression of revolts, as in Prussia's disciplined forces under Frederick the Great (1740–1786).[26] Industrialization enabled mass conscription during total wars, such as the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) and World Wars I and II, where militaries assumed logistical, industrial, and societal mobilization roles to sustain prolonged attrition.[27] Post-World War II, nuclear deterrence redefined roles in superpowers like the U.S. and USSR, emphasizing strategic stability over conquest, while the Cold War (1947–1991) involved proxy conflicts and containment.[9] The 1990s onward incorporated peacekeeping and stabilization, beginning with the UN Emergency Force (UNEF I) in 1956 for Suez Crisis monitoring, evolving to multidimensional missions by the 2000s involving disarmament, civilian protection, and election support in over 70 operations.[28][29] Contemporary militaries balance traditional combat with asymmetric warfare against non-state actors, cyber operations for domain defense, space asset protection, and non-combat functions like disaster relief, as U.S. forces demonstrated in responses to Hurricanes Katrina (2005) and Maria (2017), reflecting expanded mandates for national resilience amid hybrid threats.[9][30]Historical Foundations

Ancient and Classical Eras

The origins of organized militaries trace to ancient Mesopotamia, where the earliest documented conflict between Lagash and Umma occurred around 2525 BCE, as recorded in textual evidence and the Stele of the Vultures.[31] [32] Sumerian forces primarily comprised close-order foot soldiers armed with long spears held in both hands, numbering in the thousands for major engagements, with early units relying on leather cloaks rather than shields for protection by approximately 2800 BCE.[33] These militias evolved toward more professional elements during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112-2004 BCE), involving conscripted troops for conquests beyond Sumerian borders, though no permanent standing army existed.[34] In ancient Egypt, military structures emerged following unification circa 3200 BCE, with pharaonic forces initially focused on infantry for defense and Nile-based operations.[35] A formal standing army was established under Amenemhat I around 1991 BCE during the Middle Kingdom, enabling expansionist campaigns.[36] By the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1070 BCE), innovations like horse-drawn chariots—lightweight with six-spoked wheels—enhanced mobility, allowing crews of archers to harass infantry formations from afar, as seen in battles such as Kadesh in 1274 BCE.[37] [36] Egyptian tactics emphasized combined arms, integrating chariotry with foot soldiers equipped with bronze khopesh swords and composite bows.[38] Greek warfare shifted toward heavy infantry dominance in the Archaic period, with the hoplite phalanx forming by the 7th century BCE as a tight rectangular array of citizen-soldiers wielding 8-foot spears (doru) and large round shields (hoplon).[39] This formation, typically 8-16 ranks deep, prioritized shield-wall cohesion and thrusting over individual maneuvers, proving decisive in conflicts like the Persian Wars (490-479 BCE).[40] Macedonian adaptations under Philip II (r. 359-336 BCE) introduced the sarissa pike—up to 18 feet long—extending the phalanx's reach, paired with elite Companion cavalry for flanking attacks.[41] Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) refined these into combined-arms tactics, using the phalanx to pin enemies while cavalry executed the "hammer and anvil" maneuver, as at Gaugamela in 331 BCE where 47,000 Macedonians routed a Persian force of over 100,000.[41] This approach facilitated conquests spanning from Greece to India, emphasizing rapid marches, terrain exploitation, and psychological intimidation through disciplined drills.[42] Roman military organization in the classical era transitioned from tribal militias to the manipular legion during the Republic (c. 509-27 BCE), structuring approximately 4,200-5,000 infantry into 30 maniples of 120-160 men each, arrayed in three lines (hastati, principes, triarii) for phased engagement and flexibility against Gallic or Carthaginian foes.[43] By the late Republic and Empire, legions reorganized into 10 cohorts of 480 legionaries, supported by auxiliaries, enabling sustained professional service terms of 20-25 years and engineering feats like fortified camps.[44] Key innovations included standardized equipment (pilum javelins, gladius short swords) and cohort-based tactics, which adapted to diverse terrains from Punic Wars (264-146 BCE) to Germanic campaigns.[45] Across these eras, warfare evolved from chariot-centric mobility in the Bronze Age—spurred by spoked-wheel technology around 2000 BCE—to infantry phalanxes and cavalry integration, driven by metallurgical advances in bronze weaponry and the need for disciplined formations to counter numerical disparities.[46] [47] These developments laid foundations for state power through conquest and defense, with empirical success measured in territorial gains like Egypt's Nubian holdings or Rome's Mediterranean dominance.[37] [44]Medieval and Early Modern Periods

Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, European military organization transitioned to a decentralized feudal system by the 9th century, where lords granted land (fiefs) to vassals in exchange for military service, primarily in the form of mounted knights equipped with chain mail, lances, and swords. Armies consisted largely of these noble cavalry supplemented by peasant levies (faineants) armed with spears, axes, and bows, totaling forces often numbering in the low thousands for major campaigns; for instance, at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror's Norman army fielded approximately 7,000-8,000 men, relying on heavy cavalry charges and archers to defeat the Anglo-Saxon shield wall.[48] This structure emphasized shock tactics and personal valor over disciplined formations, with battles frequently decided by melee combat after initial archery exchanges or charges.[49] Defensive warfare dominated due to the proliferation of stone castles from the 11th century onward, making sieges—employing trebuchets, battering rams, and mining—the predominant form of conflict, as attackers sought to starve or breach fortifications rather than risk open-field annihilation. The 12th-century infantry revolution, influenced by encounters with agile horse-archer tactics during the Crusades (1095–1291 CE) and against steppe nomads, prompted European knights to dismount for combined-arms operations, elevating pikemen and crossbowmen; English longbowmen, drawing bows with up to 180-pound draw weights, decimated French knights at Agincourt in 1415, where 6,000-9,000 English archers and men-at-arms routed a larger French force through terrain-exploiting volleys and stakes. Mercenaries, such as Italian condottieri or Swiss pikemen, increasingly filled gaps in feudal levies, providing tactical flexibility but often prioritizing profit over loyalty.[50][51] The Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) marked a pivotal shift toward proto-professionalism, as cash payments supplanted feudal obligations, enabling rulers like Edward III of England to sustain armies of 10,000–20,000 through indenture contracts; early gunpowder weapons, including ribauldequins and bombards, appeared by the 1320s, though primitive and unreliable until refined in the 15th century.[51] In the early modern period (c. 1450–1789), the widespread adoption of gunpowder revolutionized tactics, with matchlock arquebuses and cannons eroding the dominance of armored knights by the mid-16th century; the Spanish tercio formation, combining pikemen for defense with musketeers for firepower, exemplified this at battles like Pavia (1525), where 30,000 Habsburg troops defeated a larger French army through disciplined volley fire.[25] The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) accelerated the formation of standing armies, as fiscal-military states like Sweden under Gustavus Adolphus fielded 100,000+ troops with linear tactics, mobile field artillery, and combined arms, contrasting medieval ad hoc levies; by 1648, European powers maintained permanent forces numbering in the tens of thousands, funded by taxation and supported by trace italienne bastion fortresses that demanded prolonged sieges with engineered approaches. This transition from feudal obligations to professional, conscript-based armies—evident in France's 30,000-man standing force by Louis XIV's reign (r. 1643–1715)—enabled sustained campaigns and colonial expansion, though logistical strains limited sizes until 18th-century reforms.[25][51] Naval warfare evolved concurrently, with galleons and broadside cannon enabling fleet actions like the Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652–1674), shifting power projection to gun-armed ships over oar-driven galleys.[52]Industrial Revolution and Total Wars

The Industrial Revolution, originating in Britain during the late 18th century, fundamentally altered warfare by enabling mass production of standardized weapons and ammunition, shifting conflicts from reliance on artisanal craftsmanship to factory-scale output. This mechanization allowed for equipping larger armies with interchangeable parts, such as rifled muskets and artillery, increasing firepower and logistical efficiency. Railroads, introduced in the 1830s, facilitated rapid troop deployments and supply lines, while steam-powered naval vessels and telegraphs enhanced mobility and command coordination, marking a departure from pre-industrial limitations where armies were constrained by foot marches and manual forging.[53][54] Early manifestations appeared in mid-19th-century conflicts, exemplified by the American Civil War (1861–1865), where industrial technologies like railroads transported over 2 million Union soldiers and supplied ironclad warships such as the USS Monitor, which engaged in the first clash of armored vessels on March 9, 1862. Rifled firearms, producing rates of fire up to three times higher than smoothbore muskets, combined with field entrenchments and early machine-gun prototypes, inflicted unprecedented casualties—totaling approximately 620,000 deaths—highlighting the mismatch between Napoleonic tactics and industrialized lethality. Similarly, the Franco-Prussian War (July 19, 1870–January 28, 1871) demonstrated Prussian mastery of rail logistics, mobilizing 1.2 million troops in weeks via 20,000 railcars, enabling encirclement victories like Sedan that captured Emperor Napoleon III and 100,000 French soldiers. These wars underscored how industrial infrastructure amplified state capacity for sustained operations, favoring nations with superior factories and transport networks.[55][56][57] This evolution culminated in the total wars of the 20th century, particularly World War I (1914–1918) and World War II (1939–1945), where belligerents committed entire economies, populations, and resources to achieve decisive victory, erasing distinctions between combatants and civilians. In WWI, mass conscription swelled armies to millions—Britain alone fielded 5.7 million men—while factories produced 250,000 artillery shells daily by 1916, fueling attritional battles like the Somme, which caused over 1 million casualties in four months due to machine guns and high-explosive shells. Total war entailed government-directed economies, rationing, and propaganda to sustain home-front production, with strategic bombing targeting industries, as in Germany's 1917 Gotha raids on London. WWII escalated this, with the U.S. output reaching 300,000 aircraft and 86,000 tanks by 1945, overwhelming Axis forces through sheer volume; Soviet production similarly emphasized quantity, manufacturing 105,000 tanks. Such mobilization, rooted in industrial scalability, prioritized economic endurance over limited engagements, resulting in 70–85 million deaths, including civilian targeting via firebombing and atomic strikes.[58][59][60]Cold War Dynamics

The Cold War era (approximately 1947–1991) saw the United States and its NATO allies confront the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact in a sustained military rivalry defined by nuclear deterrence, conventional force deployments in Europe, and indirect conflicts via proxy wars, all underpinned by an arms race that prioritized strategic stability over direct confrontation. NATO, established on April 4, 1949, as a collective defense pact under Article 5, countered perceived Soviet expansionism in Europe, while the Warsaw Pact formed on May 14, 1955, as a Soviet-led response to West German rearmament, formalizing the division of the continent. This bipolar structure deterred large-scale conventional war in Europe through the doctrine of mutually assured destruction (MAD), where each side's nuclear capabilities ensured retaliatory devastation; by the late 1960s, the U.S. nuclear stockpile peaked at 31,255 warheads, enabling overkill capacity far exceeding strategic needs. Soviet forces, emphasizing quantity, amassed superior ground troop numbers—approximately 175 divisions by the 1980s compared to NATO's 100—and 70,000 tanks against NATO's 30,000 by 1980, yet suffered from qualitative deficiencies in technology and logistics.[61][62][63] In Central Europe, the primary theater of potential conventional conflict, Warsaw Pact doctrine focused on rapid armored offensives through corridors like the Fulda Gap in West Germany, a 60-mile-wide lowland historically exploited for invasions since antiquity, which U.S. planners identified as a likely axis for Soviet breakthroughs toward the Rhine River. To counter this, NATO maintained forward-deployed forces, including U.S. VII Corps, while conducting annual REFORGER (Return of Forces to Germany) exercises from 1969 to 1993, simulating the rapid airlift and sealift of up to 100,000 U.S. troops and equipment from North America to reinforce the Central Front within days, thereby testing interoperability and deterrence credibility against Soviet numerical advantages. Soviet military expenditures, estimated by CIA analyses at equivalent dollar costs exceeding U.S. outlays in certain categories like tank procurement, strained the command economy, contributing to inefficiencies such as outdated equipment and poor maintenance, while U.S. investments yielded technological edges in areas like computer-assisted command systems and precision-guided munitions. Declassified CIA comparisons from the 1970s highlighted Soviet procurement of 20,000–25,000 main battle tanks annually in peak years versus U.S. figures of 1,000–2,000, underscoring the asymmetry in force generation but also the USSR's reliance on mass over innovation.[64][65][61][66] Proxy wars allowed superpowers to extend influence without risking nuclear escalation, with the U.S. committing over 1.8 million personnel to the Korean War (1950–1953) to repel North Korean and Chinese forces backed by Soviet arms and advisors, resulting in 36,574 U.S. fatalities. In Vietnam (1955–1975), U.S. involvement peaked at 543,000 troops in 1969, combating North Vietnamese regulars supplied via the Ho Chi Minh Trail with Soviet and Chinese matériel, culminating in 58,220 U.S. deaths amid debates over containment efficacy. The Soviet intervention in Afghanistan (1979–1989) mirrored this dynamic inversely, deploying 620,000 troops against mujahideen guerrillas armed by U.S. Stinger missiles and Pakistani intermediaries, incurring 14,453 Soviet fatalities and exposing logistical vulnerabilities in rugged terrain. These conflicts, alongside others in Angola and Nicaragua, amplified global military engagements—totaling over 40 proxy involvements—while reinforcing deterrence in Europe by diverting resources and testing indirect strategies.[67] By the 1980s, asymmetries in sustainability eroded Soviet advantages: U.S. defense spending averaged 6–7% of GDP under Reagan's buildup, funding initiatives like the Strategic Defense Initiative, while Soviet allocations reached 15–20% of GDP per some estimates, exacerbating economic stagnation and technological lags in microelectronics and avionics. The 1972 SALT I Treaty and 1979 SALT II (though unratified) capped strategic nuclear delivery vehicles at 2,400 and MIRVed missiles at 1,320 each, stabilizing arsenals but not resolving conventional imbalances. Ultimately, these dynamics contributed to the USSR's 1991 collapse, as military overextension—evident in Afghanistan's quagmire and Europe's unsustainable garrisons—interacted with internal reforms under Gorbachev, validating NATO's forward defense without a single shot fired on the continent.[61][68][69]Post-1991 Conflicts and Asymmetric Warfare

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991 marked the end of the Cold War bipolar standoff, leading to a decline in interstate conflicts between major powers and a rise in intrastate wars, ethnic conflicts, and non-state actor challenges. From 1990 to 2005, the number of major armed conflicts decreased from peaks in the early 1990s, with most involving internal struggles over governance, particularly in Asia and Africa. This era saw militaries of advanced nations, equipped for symmetric peer competition, increasingly engaged in asymmetric warfare, where adversaries exploited disparities in conventional strength through irregular tactics like ambushes, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and terrorism to impose disproportionate costs.[70] The 1991 Persian Gulf War exemplified a transitional conventional operation, as a U.S.-led coalition of over 30 nations swiftly liberated Kuwait from Iraqi occupation following Iraq's August 2, 1990, invasion. Ground operations lasted 100 hours from February 24 to 28, 1991, resulting in 147 U.S. hostile deaths and total coalition fatalities around 345, contrasted with Iraqi military losses estimated at 20,000 to 50,000 killed. Precision-guided munitions and overwhelming air superiority minimized friendly casualties while devastating Iraqi forces, highlighting technological edges in symmetric engagements but foreshadowing limitations in post-invasion stabilization. Subsequent interventions, such as U.N. operations in Somalia (1992–1993) and the Balkans (1990s), introduced peacekeeping and limited strikes against irregular foes, exposing vulnerabilities to urban combat and non-combatant complexities.[71][72] Asymmetric warfare, characterized by weaker parties avoiding decisive battles in favor of protracted attrition through insurgency, terrorism, and information operations, dominated post-1991 U.S. and allied experiences. The September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda attacks prompted the Global War on Terror, launching Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, which toppled the Taliban regime within months but devolved into a 20-year counterinsurgency against resilient guerrilla networks. U.S. military fatalities in Afghanistan reached approximately 2,459 by the 2021 withdrawal, with Taliban tactics emphasizing IEDs—responsible for over 60% of casualties—and sanctuary in Pakistan enabling regeneration. In Iraq, the 2003 invasion achieved regime change rapidly, but the ensuing insurgency and al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) violence peaked in 2006–2007, costing over 4,400 U.S. lives across Operations Iraqi Freedom and New Dawn through 2011.[73][74] Military adaptations emphasized counterinsurgency (COIN) doctrines, integrating kinetic operations with governance and development to secure populations. The 2007 Iraq surge deployed an additional 20,000–30,000 U.S. troops, fostering alliances with Sunni tribes against AQI and reducing sectarian violence by over 80% in key areas by 2008. Enhanced intelligence fusion, special operations raids, and drone strikes disrupted networks, as seen in the May 2, 2011, operation killing Osama bin Laden. Yet, challenges persisted: insurgents adapted faster in some cases, exploiting local grievances and corrupt governance, leading to Taliban resurgence in Afghanistan and ISIS emergence in Iraq by 2014. Financial costs exceeded $2 trillion for post-9/11 wars, underscoring the inefficiency of conventional forces in asymmetric contexts without sustained political commitment.[75][76] Recent conflicts, including the U.S.-led campaign against ISIS (2014–2019) and Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, blend asymmetric elements like cyber attacks, drones, and hybrid tactics with conventional maneuvering. In Ukraine, both sides employed low-cost unmanned systems and artillery duels, with Ukrainian forces using Western precision weapons to offset numerical disadvantages, resulting in over 500,000 combined casualties by mid-2024 estimates from official and think-tank analyses. These engagements reveal ongoing evolution toward multi-domain operations, where militaries invest in rapid adaptation, resilient logistics, and information dominance to counter asymmetric threats that prolong conflicts and erode public support in democratic societies.[77]Organizational Elements

Personnel Systems

Military personnel systems encompass the processes for acquiring, training, managing, and retaining service members to maintain operational readiness. These systems vary by nation but generally distinguish between all-volunteer forces (AVF), which rely on voluntary enlistment, and conscript-based models that mandate service for eligible citizens. The United States adopted an AVF in 1973, ending the draft after the Vietnam War, resulting in a more professional force with higher retention rates and specialized skills compared to conscript armies, though it incurs higher personnel costs due to competitive pay and benefits.[78] Conscription, used by countries like Israel, South Korea, and Russia, expands force size rapidly during mobilization but often yields lower unit cohesion and expertise, as involuntary service correlates with reduced motivation and higher desertion risks; empirical studies indicate conscripts perform adequately in short conflicts but lag in complex, technology-intensive operations.[79][80] Recruitment in AVF nations like the U.S. involves eligibility screening for age (typically 17-35), education (high school diploma preferred), physical fitness, and moral character, with recruiters assessing applicants via interviews, aptitude tests like the ASVAB, and medical exams.[81][82] In 2023, the U.S. Army faced recruitment shortfalls of about 15,000 soldiers amid a competitive labor market, prompting incentives such as enlistment bonuses up to $50,000 and expanded eligibility for prior-service or GED holders.[83] Conscript systems, by contrast, employ centralized drafts with exemptions for students or essential workers, as in Russia's 2024 mobilization of 150,000 reserves, which prioritized quantity over quality and faced evasion rates exceeding 20% in some regions.[84] Initial training, or basic military training, instills discipline, physical conditioning, and core combat skills over 8-13 weeks, depending on the branch; U.S. Army basic combat training, for instance, includes marksmanship, tactics, and team-building exercises to forge unit cohesion.[85] Advanced individual training follows for job-specific qualifications, such as infantry or cyber operations, extending total entry-level preparation to 10-20 weeks.[86] Officer training, via academies like West Point or ROTC programs, emphasizes leadership and strategy over 4 years, producing leaders accountable for personnel welfare and mission execution.[87] Rank structures establish command hierarchies, with enlisted ranks (e.g., U.S. Army private to sergeant major, E-1 to E-9) handling tactical execution and non-commissioned officers providing mentorship, while warrant and commissioned officers (O-1 to O-10) oversee strategy and policy.[88] Promotions blend time-in-service, performance evaluations, and selection boards; enlisted advancements to E-5 (sergeant) require 24-36 months and demonstrated leadership, with competitive rates below 50% for higher grades due to limited slots.[89] Retention relies on career progression, pay scales (e.g., U.S. E-1 base pay of $1,917 monthly in 2024), and family support, though AVF systems grapple with burnout in high-ops tempo eras, as seen in post-9/11 extension rates.[90] Integrated systems like the U.S. Army's IPPS-A digitize pay, assignments, and evaluations to enhance efficiency and reduce administrative errors affecting 1.3 million active personnel.[91]Unit and Command Structures

Military units are hierarchically organized to optimize command, control, logistics, and tactical maneuverability, with smaller elements forming larger formations for scalable operations. In conventional ground forces, such as those of the U.S. Army, the foundational unit is the squad, typically consisting of 9 soldiers divided into two 4-man fire teams plus a squad leader (sergeant) responsible for direct combat tasks.[92] Three to four squads, along with a small headquarters, form a platoon of approximately 36 soldiers, commanded by a lieutenant who coordinates fire and movement.[93] Companies integrate 3-5 platoons with support elements, totaling 100-200 personnel under a captain, enabling independent tactical engagements like assaults or defenses.[94] Battalions combine 3-5 companies plus specialized attachments (e.g., reconnaissance or mortar platoons), ranging from 300-1,000 soldiers and led by a lieutenant colonel, focusing on sustained combat over broader areas.[95] Brigades, comprising multiple battalions with integrated combat support (artillery, engineers), scale to 3,000-5,000 troops under a colonel, serving as the primary maneuver unit in modern doctrines for flexibility in joint operations.[94] Divisions aggregate 3-5 brigades with enablers like aviation and logistics, encompassing 10,000-20,000 personnel commanded by a major general, designed for theater-level campaigns.[94] Larger echelons include corps (20,000-45,000 soldiers, lieutenant general) for operational coordination across divisions and field armies (50,000+, general) for strategic theater command.[94]| Unit | Approximate Size | Commander Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Squad | 9 soldiers | Sergeant |

| Platoon | 30-40 soldiers | Lieutenant |

| Company | 100-200 soldiers | Captain |

| Battalion | 300-1,000 soldiers | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Brigade | 3,000-5,000 soldiers | Colonel |

| Division | 10,000-20,000 soldiers | Major General |

| Corps | 20,000-45,000 soldiers | Lieutenant General |

![Map of military expenditures as a percentage of GDP by country, 2017[37][needs update]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Military_Expenditures_as_percent_of_GDP_2017.png/500px-Military_Expenditures_as_percent_of_GDP_2017.png)