Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Analects.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Analects

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

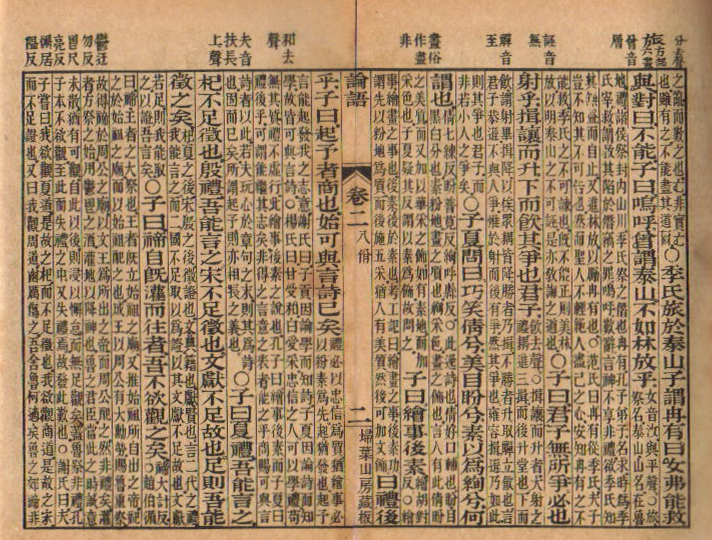

Analects

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

The Analects (Chinese: 論語; pinyin: Lúnyǔ; literally "collated sayings"), also known as the Analects of Confucius, is an ancient Chinese text comprising a collection of brief passages that record sayings, teachings, and anecdotes attributed to the philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE) and his disciples.[1][2] The work emphasizes ethical principles such as benevolence (ren), ritual propriety (li), and personal cultivation, alongside guidance on governance, social relationships, and moral self-improvement, presenting Confucius as a model teacher and sage.[3] Structured in 20 chapters, each titled by its opening phrase (e.g., "Xue er" or "Learning"), the text takes the form of terse dialogues and reflections rather than systematic exposition, reflecting oral traditions preserved and edited over time.[1]

Compiled by Confucius's immediate followers and subsequent generations, the Analects emerged gradually between the late 5th and 3rd centuries BCE, with its core likely dating to the early 4th century BCE based on references to post-Confucius figures.[3][1] Scholarly analysis reveals layered composition, including early strata in Books III–VII and later additions, evidenced by archaeological finds like bamboo manuscripts from sites such as Dingzhou (55 BCE).[2] Multiple versions circulated in the Han dynasty (e.g., Lu, Qi, and Gu editions with varying chapter counts), but the standard 20-chapter form was established by the 2nd century BCE and later canonized in compilations like He Yan's 3rd-century CE edition.[1] While debates persist on precise authorship and authenticity—due to internal inconsistencies and the text's evolution from diverse Confucian lineages—the Analects remains the most direct and reliable transmitted source for Confucius's thought.[2]

As the cornerstone of Confucianism, the Analects profoundly shaped East Asian intellectual traditions, informing imperial examination systems, ethical norms, and political philosophy for over two millennia, with virtues like filial piety (xiao) and the ideal of the exemplary person (junzi) central to its enduring legacy.[3][1] Its influence extended through extensive commentaries, from Han-era scholars to Song dynasty synthesizers like Zhu Xi, embedding Confucian realism in hierarchies of duty and ritual over abstract metaphysics.[1]