Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

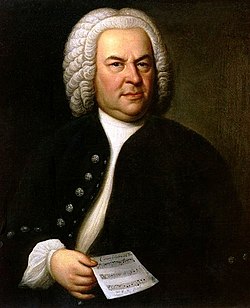

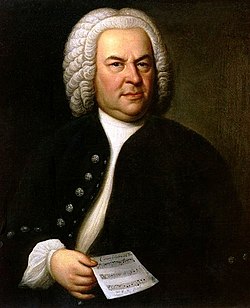

English Suites (Bach)

View on Wikipedia

The English Suites, BWV 806–811, are a set of six suites written by the German composer Johann Sebastian Bach for harpsichord (or clavichord) and generally thought to be the earliest of his 19 suites for keyboard (discounting several less well-known earlier suites), the others being the six French Suites (BWV 812–817), the six Partitas (BWV 825-830) and the Overture in the French style (BWV 831). They probably date from around 1713 or 1714 until 1720.[1]

History

[edit]These six suites for keyboard are thought to be the earliest set that Bach composed aside from several miscellaneous suites written when he was much younger. Bach's English Suites display less affinity with Baroque English keyboard style than do the French Suites to French Baroque keyboard style. It has also been suggested that the name is a tribute to Charles Dieupart, whose fame was greatest in England, and on whose Six Suittes de clavessin Bach's English Suites were in part based.[2]

Surface characteristics of the English Suites strongly resemble those of Bach's French Suites and Partitas, particularly in the sequential dance-movement structural organization and treatment of ornamentation. These suites also resemble the Baroque French keyboard suite typified by the generation of composers including Jean-Henri d'Anglebert, and the dance-suite tradition of French lutenists that preceded it.

In the English Suites especially, Bach's affinity with French lute music is demonstrated by his inclusion of a prelude for each suite, departing from an earlier tradition of German derivations of French suite (those of Johann Jakob Froberger and Georg Boehm are examples), which saw a relatively strict progression of the dance movements (Allemande, Courante, Sarabande and Gigue) and which did not typically feature a Prelude. Unlike the unmeasured preludes of French lute or keyboard style, however, Bach's preludes in the English Suites are composed in strict meter.

The suites

[edit]The six suites are:

|

|

This first suite is unusual in that it has two courantes and two doubles for the second courante. This suite also departs from the scheme of the other five, in that the prelude is short and based on a theme from a suite by Dieupart. The preludes of the other five suites in this series are based on the allegro of a concerto grosso form.

The key sequence follows the same series of notes as the chorale "Jesu, meine Freude"; it is unestablished whether or not this is coincidental.

Notable recordings

[edit]On harpsichord

[edit]- Wanda Landowska (No. 2, 3 & 5, Pearl, 1928–35)

- Ralph Kirkpatrick (Archiv Produktion, 1956)

- Helmut Walcha (EMI Electrola, 1959)

- Martin Galling (Murray Hill, 1970 [recorded in 1964])

- Kenneth Gilbert (Harmonia Mundi, 1981)

- Zuzana Růžičková (Supraphon/Eterna, 1981)

- Christiane Jaccottet (Saphir/Disky, 1982)

- Gustav Leonhardt (Virgin, 1984)

- Huguette Dreyfus (Archiv Produktion, 1974, 1990)

- Colin Tilney (Music&Arts, 1993)

- Trevor Pinnock (Archiv Production, 1992)

- Peter Watchorn (Musica Omnia, 1997)

- Pascal Dubreuil (Ramée, 2013)

- Ketil Haugsand (Simax Classics, 2014)

On piano

[edit]- Walter Gieseking (Nos. 2–4 & 6, Music & Arts, 1950)

- Alexander Borovsky (Vox, 1952)

- Tatiana Nikolayeva (Nos. 1 & 4, Scribendum, 1965)

- Friedrich Gulda (Nos. 2 & 3, Andante, 1969–70)

- Wilhelm Kempff (No. 3, Deutsche Grammophon, 1975)

- Glenn Gould (Columbia/Sony, 1977)

- Mieczysław Horszowski (No. 3, Pearl, 1979; No. 2, Arbiter, 1984; No. 5, RCA Japan, 1987)

- Ivo Pogorelić (Nos. 2 & 3, Deutsche Grammophon, 1985)

- András Schiff (Decca, 1988, 2003 Live in Hungary)

- Wolfgang Rübsam (Naxos, 1995)

- João Carlos Martins (Concord Concerto / Labor Records / Tomato Music, 1995–1996)

- Rosalyn Tureck (No. 3, Video Artists International, 1993)

- Murray Perahia (Sony Classics, 1997)

- Robert Levin (Hänssler, 1999)

- Martha Argerich (No. 2, Deutsche Grammophon, 1979)

- Ivo Janssen (Void, 2000)

- Angela Hewitt (Hyperion, 2003)

- Sviatoslav Richter, (Delos, 2004)

- Vladimir Feltsman (Nimbus, 2005)

- Ramin Bahrami (Decca, 2012)

- Piotr Anderszewski (No. 6, Accord, 1996))

- Piotr Anderszewski (No. 6, Erato/Warner Classics, 2004)

- Piotr Anderszewski (Nos. 1, 3 & 5, Warner Classics, 2014)

On cello

[edit]- Pablo Casals (Gavottes I and II from English Suite No. 6, BWV 811, arr. Fernand Pollain; Naxos Historical 8.110915-16)

Media

[edit]|

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]External links

[edit]- English Suites: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- English Suite No. 1, English Suite No. 2, English Suite No. 3 and English Suite No. 4: performances by the Netherlands Bach Society (video and background information)

English Suites (Bach)

View on GrokipediaBackground and Composition

Historical Context

Johann Sebastian Bach was appointed court organist at the ducal court of Weimar in 1708, a position that allowed him to deepen his expertise in keyboard music amid the demands of the court's musical establishment. During his tenure there from 1708 to 1717, Bach composed a significant body of organ and harpsichord works, benefiting from access to the court's instruments and his role in providing music for services and performances. In 1714, he was promoted to Konzertmeister, further emphasizing his focus on instrumental composition, including early developments in suite forms.[5] The English Suites, BWV 806–811, were likely composed during Bach's late Weimar years and early in his subsequent appointment, spanning approximately 1710 to 1720 as part of his early mature period for solo keyboard music. In 1717, Bach transitioned to the role of Kapellmeister at the court of Prince Leopold in Cöthen, where the Calvinist environment prioritized secular instrumental music over vocal church works, creating an ideal setting for the flourishing of keyboard compositions like the suites. This keyboard-centric milieu at Cöthen enabled Bach to refine and possibly complete the English Suites, aligning with the court's emphasis on chamber music for harpsichord and other instruments.[6] The designation "English Suites" originated posthumously and remains a subject of debate, with no evidence that Bach himself used the term or intended them for English performance. Bach's first biographer, Johann Nikolaus Forkel, asserted in 1802 that the suites were composed for "an Englishman of rank," a claim echoed in early manuscript references but lacking specific identification of the dedicatee. Scholars also link the title to Bach's study and copying of six harpsichord suites by the French composer Charles Dieupart, published in Amsterdam around 1701, whose structure and style may have influenced Bach's model during his Weimar period circa 1713.[2][7]Influences and Origins

The English Suites, BWV 806–811, draw significant inspiration from Charles Dieupart's Six Suittes de clavessin (c. 1701), a collection of harpsichord suites that Bach copied out entirely for his own study during his Weimar years (1708–1717). This influence is particularly evident in the prelude of the first suite (BWV 806), where Bach directly quotes and adapts the gigue from Dieupart's A major suite, transforming it into a more elaborate keyboard prelude with contrapuntal development. Dieupart, a French composer active in London, introduced a dynamic structure to the keyboard suite that emphasized virtuosic preludes, a model Bach adopted to elevate the genre beyond traditional dance sequences.[2][8] Bach further incorporated French Baroque elements, synthesizing them with his German contrapuntal style, as seen in the sarabandes' use of ornamental agréments and rhythmic nuances reminiscent of François Couperin's Pièces de clavecin. Couperin's approach to les goûts réunis—blending national styles—influenced Bach's fusion of French dance elegance with Italian vitality, particularly in the allemandes and courantes that evoke the refined poise of Versailles court music. Additionally, the suites reflect traditions of French lute music through broken chord textures (style brisé) in movements like the sarabande doubles, which mimic the arpeggiated patterns of lutenists such as Robert de Visée, adapting them for keyboard to create a harp-like resonance.[2][9] Departing from the more austere German suite norms exemplified by composers like Johann Kuhnau, Bach prefixed each suite with a prelude, drawing from Italian concerto grosso forms pioneered by Arcangelo Corelli. The opening movements, especially in suites BWV 807–811, emulate Corelli's Op. 6 concertos through ritornello structures and idiomatic violinistic figuration, infusing the keyboard with orchestral energy and motivic dialogue between soloistic and fuller textures. This Italianate innovation expanded the suite's introductory role, contrasting with the predominantly dance-focused German models.[9][10] The designation "English Suites" likely stems from a possible dedication to an English patron, despite the prevailing French stylistic dominance; Johann Nikolaus Forkel's 1802 biography notes they were composed for "an Englishman of rank," though no specific identity is confirmed. A manuscript copy by Bach's son Johann Christian, who resided in London, labels them fait pour les Anglois ("made for the English"), suggesting a performance context tied to English nobility around the time of George I's 1714 accession. This naming may also honor Dieupart's prominence in England, underscoring the suites' cross-cultural synthesis.[2][11]Manuscripts and Editions

Surviving Sources

The autograph manuscript of Johann Sebastian Bach's English Suites (BWV 806–811) has not survived, leaving scholars reliant on contemporary copies made by his pupils and associates for textual transmission. The most authoritative early sources include four manuscripts copied by Bach's student Heinrich Nikolaus Gerber around 1724–1725 during his studies in Leipzig, containing the suites in A major (BWV 806), G major (BWV 808), E minor (BWV 810), and D minor (BWV 811); these are preserved as Mus. ms. Bach P 805–807 and P 225 in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin and provide crucial evidence of the works' early dissemination due to their proximity to the presumed composition period (ca. 1715–1720) and inclusion of some ornamentation possibly added by Bach himself.[12][13] Recently, in 2024, these Gerber manuscripts were acquired by the Bach-Archiv Leipzig and are now exhibited there.[12] Another key source is the copy of the A minor suite (BWV 807) by pupil Johann Tobias Krebs, dating from ca. 1725–1750 and held as Mus. ms. Bach P 803 in the same library, valued for its fidelity to Bach's teaching materials and early notational details.[14] Additional manuscript copies from the mid-18th century document variants across the set, aiding modern editions in reconstructing likely authentic readings amid textual discrepancies.[15] During World War II, the Berlin State Library's collections, including these Bach manuscripts, were evacuated to remote locations like Silesia and the Soviet Union for protection, resulting in the temporary loss or displacement of some items; however, the principal sources for the English Suites were recovered and repatriated to the library in the years following 1945, ensuring their availability for postwar scholarship. The cohesive grouping of the six suites as BWV 806–811 was formalized in Wolfgang Schmieder's Thematisch-systematisches Verzeichnis der musikalischen Werke von Johann Sebastian Bach, first published in 1950, which cataloged them based on their shared stylistic and structural features observed in the surviving copies.[16]Publication History

The first complete printed edition of the English Suites was published in 1841, edited by Carl Czerny and issued by Tobias Haslinger in Vienna, appearing as part of efforts to compile Bach's keyboard works.[17] This posthumous edition, based on available manuscripts, marked the suites' initial dissemination beyond handwritten sources and contributed to their gradual integration into the Romantic-era keyboard repertoire.[18] In the 19th century, editors adapted the suites for the emerging piano, with Carl Czerny's 1837 edition (published by Tobias Haslinger in Vienna) introducing fingerings and interpretive suggestions tailored to piano technique, emphasizing legato phrasing and dynamic contrasts absent in Baroque performance practice.[19] Similarly, Hans von Bülow's edition, issued around 1881 by Breitkopf & Härtel, further promoted piano-specific realizations, including pedal indications and expressive markings that reflected the 19th-century aesthetic of emotional depth and virtuosity.[20] These editions, while diverging from original sources, played a key role in popularizing the suites among pianists during the Bach revival. Twentieth-century scholarship shifted toward critical editions faithful to primary sources, such as the Bärenreiter edition (New Bach Edition, vol. V/7) edited by Alfred Dürr, published in 1978, which restored authentic phrasing and ornamentation.[21] The Henle Verlag edition from the 1970s, edited by Alfred Dürr, advanced this approach by collating multiple manuscript variants to provide an urtext free of editorial interventions and highlighting textual discrepancies among surviving copies. Contemporary urtext editions, such as revised versions from Bärenreiter and Henle in the 21st century, build on these foundations by integrating recent research on Baroque ornamentation, tempo conventions, and historical performance, often drawing from digitized manuscript materials to offer performers options for authentic realization.[21]Structure and Movements

Overall Organization

The English Suites, BWV 806–811, consist of six keyboard suites composed by Johann Sebastian Bach, set in the keys of A major (No. 1), A minor (No. 2), G minor (No. 3), F major (No. 4), E minor (No. 5), and D minor (No. 6). These works follow a unified architectural template that reflects the Baroque suite tradition while incorporating Bach's distinctive expansions, creating a cohesive set despite individual variations in movement count (ranging from seven to ten per suite).[1] The overall design emphasizes a progression from introductory flourish to danced elaboration, culminating in energetic closure, with the entire collection demonstrating Bach's synthesis of national styles into a German contrapuntal framework.[2] Each suite opens with a Prelude, an addition not found in all Baroque suites, typically in the style of an Italian concerto grosso with ritornello form and idiomatic keyboard writing evoking orchestral textures, though the sixth employs French overture characteristics such as a slow dotted section followed by a faster fugal part.[2] This is followed by the core dance movements: an Allemande, typically one or two Courantes (with the second often in a contrasting style), a Sarabande, and a Gigue. Between the Sarabande and Gigue, Bach inserts one or two optional galant dances—such as Bourrées, Gavottes, Menuets, or Passepieds—providing rhythmic variety and lighter interlude.[7] The dances adhere predominantly to binary form, with each divided into two sections (A and B) that explore the tonic and dominant keys before returning, often marked for repeats to enhance structural depth.[1] Some of the inserted dances employ da capo form (ABA), repeating the initial section after a contrasting middle to create symmetrical elegance.[2] In performance, each suite typically lasts 15 to 25 minutes, depending on tempi and observance of repeats, allowing for a balanced program when the set is played complete (approximately two hours total).[22] The series exhibits stylistic unity through its consistent adherence to dance-derived rhythms and meters, enriched by Bach's polyphonic writing, while the complexity builds progressively from the relatively straightforward No. 1 to the chromatically intense and contrapuntally demanding Nos. 5 and 6, which Forkel described as pinnacles of keyboard artistry.[2] This escalation underscores the suites' role as a comprehensive study in Baroque keyboard technique and expression.[23]Descriptions of Individual Suites

Suite No. 1 in A major, BWV 806The first English Suite opens with a Prelude that quotes and develops a gigue from Charles Dieupart's harpsichord suites, featuring an improvisatory flourish and compact structure with Italianate figuration.[7] This is followed by an Allemande, two Courantes—the second with two accompanying Doubles—a Sarabande, two Bourrées, and a Gigue, all in binary form typical of the genre. The suite's movements emphasize elegant ornamentation and rhythmic vitality, with the Doubles providing variations on the Courante's melody.[24] Suite No. 2 in A minor, BWV 807

Suite No. 2 begins with a Prelude structured as a three-voice fugue, showcasing intricate contrapuntal development and a lively subject that recurs throughout the movement. The subsequent movements include an Allemande, a single Courante, a Sarabande with an ornamented variant titled "Les agréments de la même Sarabande," two Bourrées (one marked "alternativement"), and a Gigue. This suite highlights Bach's skill in balancing fugal complexity with the graceful flow of dance forms, particularly in the paired Bourrées that contrast major and minor tonalities.[25][17] Suite No. 3 in G minor, BWV 808

The Prelude of the third suite adopts a concerto-like form with ritornello structure, resembling a 17th-century concerto grosso through its alternating tutti and solo-like passages in two-part writing. It precedes an Allemande, a Courante, a Sarabande, two Gavottes—the second subtitled "ou la Musette" with a drone bass—and a concluding Gigue. The movements feature robust energy and textural variety, with the Musette evoking pastoral bagpipe effects via sustained pedal tones.[26][27] Suite No. 4 in F major, BWV 809

This suite commences with a Prelude characterized by arpeggiated figures and idiomatic keyboard writing, leading into an Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, two Menuets—the second marked "da capo" for repetition—and a Gigue. The Menuets provide a lighter, galant contrast to the more elaborate dances, with the da capo indication encouraging structural repetition. Overall, the suite maintains a bright, energetic tone suited to the major key, emphasizing clarity and balance in its binary forms.[28][20] Suite No. 5 in E minor, BWV 810

The Prelude in the fifth suite unfolds as a chromatic fantasy, employing extensive chromaticism and dramatic harmonic progressions reminiscent of Bach's earlier keyboard fantasias. It is followed by an Allemande, two Courantes, a Sarabande, two Passepieds—the first in rondeau form—and a Gigue. The paired Courantes and Passepieds offer rhythmic diversity, with the rondeau structure adding cyclical repetition to the lighter dance. This suite stands out for its expressive depth and technical demands.[29][2] Suite No. 6 in D minor, BWV 811

Opening with a Prelude in French overture style, featuring slow dotted rhythms and a faster fugal section, the sixth suite continues with an Allemande, a Courante with Double, a Sarabande with Double, two Gavottes—the second as a Musette—and a Gigue. The doubles provide embellished variations on their respective dances, enhancing the suite's ornamental richness, while the overture prelude sets a grand, theatrical tone. This final suite is the longest and most elaborate, reflecting Bach's mature synthesis of national styles.[30][31]