Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Berlin

View on Wikipedia

Berlin[a] is the capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and population.[10] With 3.7 million inhabitants,[5] it has the highest population within its city limits of any city in the European Union, and the fifth largest in Europe after Istanbul, Moscow, London and St Petersburg. The city is also one of the states of Germany, being the third-smallest state in the country by area. Berlin is surrounded by the state of Brandenburg, and Brandenburg's capital Potsdam is nearby. The urban area of Berlin has a population of over 4.6 million, making it the most populous in Germany.[6][11] The Berlin-Brandenburg capital region has around 6.2 million inhabitants and is Germany's second-largest metropolitan region after the Rhine-Ruhr region,[5] as well as the fifth-biggest metropolitan region by GDP in the European Union.[12]

Key Information

Berlin was built along the banks of the Spree river, which flows into the Havel in the western borough of Spandau. The city includes lakes in the western and southeastern boroughs, the largest of which is Müggelsee. About one-third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks and gardens, rivers, canals, and lakes.[13]

First documented in the 13th century[9] and at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[14] Berlin was designated the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), German Empire (1871–1918), Weimar Republic (1919–1933), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). Berlin served as a scientific, artistic, and philosophical hub during the Age of Enlightenment, Neoclassicism, and the German revolutions of 1848–1849. During the Gründerzeit, an industrialization-induced economic boom triggered a rapid population increase in Berlin. 1920s Berlin was the third-largest city in the world by population.[15] After World War II and following Berlin's occupation, the city was split into West Berlin and East Berlin, divided by the Berlin Wall.[16] East Berlin was declared the capital of East Germany, while Bonn became the West German capital. Following German reunification in 1990, Berlin once again became the capital of all of Germany. Due to its geographic location and history, Berlin has been called "the heart of Europe".[17][18][19]

Berlin is a global city of culture, politics, media and science.[20][21][22][23] Its economy is based on high tech and the service sector, encompassing a diverse range of creative industries, startup companies, research facilities, and media corporations.[24][25] Berlin serves as a continental hub for air and rail traffic and has a complex public transportation network. Tourism in Berlin makes the city a popular global destination.[26] Significant industries include information technology, the healthcare industry, biomedical engineering, biotechnology, the automotive industry, and electronics.

Berlin is home to several universities, such as the Humboldt University of Berlin, Technische Universität Berlin, the Berlin University of the Arts and the Free University of Berlin. The Berlin Zoological Garden is the most visited zoo in Europe. Babelsberg Studio is the world's first large-scale movie studio complex, and there are many films set in Berlin.[27] Berlin is home to three World Heritage Sites: Museum Island, the Palaces and Parks of Potsdam and Berlin, and the Berlin Modernism Housing Estates.[28] Other landmarks include the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag building, Potsdamer Platz, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, and the Berlin Wall Memorial. Berlin has numerous museums, galleries, and libraries.

History

[edit]

Brandenburg 1237–1660

Brandenburg-Prussia 1660–1701

Prussia 1701–1867

North German Confederation 1867–1871

German Reich 1871–1943

Greater German Reich 1943–1945

Empire 1871–1918

Republic 1918–1933

National Socialist dictatorship 1933–1945

Allied-occupied Berlin 1945–1990

Germany from 1990

Etymology

[edit]Berlin lies in northeastern Germany, in an area formerly settled by Slavs which thus exhibits many (Germanized) Slavic-derived placenames until today (see below). The word Berlin also has its roots in the language of the West Slavs, and may be related to the Old Polabian stem berl-/birl- ("swamp").[29]

Of Berlin's twelve boroughs, five bear a Slavic-derived name—Pankow, Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Marzahn-Hellersdorf, Treptow-Köpenick and Spandau; furthermore, across the city's 96 neighborhoods, there are 22 which bear a Slavic-rooted name—Altglienicke, Alt-Treptow, Britz, Buch, Buckow, Gatow, Karow, Kladow, Köpenick, Lankwitz, Lübars, Malchow, Marzahn, Pankow, Prenzlauer Berg, Rudow, Schmöckwitz, Spandau, Stadtrandsiedlung Malchow, Steglitz, Tegel and Zehlendorf.

Prehistory

[edit]The area of what is now Berlin has been settled for millennia.[30] A deer mask, dated to 9,000 BCE, is attributed to the Maglemosian culture. Around 2,000 BCE dense human settlements along the Spree and Havel rivers gave rise to the Lusatian culture.[31] Starting around 500 BCE Germanic tribes settled in a number of villages in the higher situated areas of today's Berlin. After the Semnones left around 200 CE, the Burgundians followed. In the 7th century Slavic tribes, the later known Hevelli and Sprevane, reached the region.

12th century to 16th century

[edit]

In the 12th century the region came under German rule as part of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, founded by Albert the Bear in 1157. Early evidence of middle age settlements in the area of today's Berlin are remnants of a house foundation dated 1270 to 1290, found in excavations in Berlin Mitte.[32] The first written records of towns in the area of present-day Berlin date from the late 12th century. Spandau is first mentioned in 1197 and Köpenick in 1209.[33] 1237 is considered the founding date of the city.[34] The two towns over time formed close economic and social ties, and profited from the staple right on the two important trade routes. One was known as Via Imperii, and the other trade route reached from Bruges to Novgorod.[14] In 1307 the two towns formed an alliance with a common external policy, their internal administrations still being separated.[35] In 1326 the territory of Berlin was raided by pagan Lithuanians during the Raid on Brandenburg.

Members of the Hohenzollern family ruled in Berlin until 1918, first as electors of Brandenburg, then as kings of Prussia, and eventually as German emperors. In 1443, Frederick II Irontooth started the construction of a new royal palace in the twin city Berlin-Cölln. The protests of the town citizens against the building culminated in 1448, in the "Berlin Indignation" (German: Berliner Unwille).[36] Officially, the Berlin-Cölln palace became permanent residence of the Brandenburg electors of the Hohenzollerns from 1486, when John Cicero came to power.[37] Berlin-Cölln, however, had to give up its status as a free Hanseatic League city. In 1539, the electors and the city officially became Lutheran.[38]

17th to 19th centuries

[edit]The Thirty Years' War between 1618 and 1648 devastated Berlin. One third of its houses were damaged or destroyed, and the city lost half of its population.[39] Frederick William, known as the "Great Elector", who had succeeded his father George William as ruler in 1640, initiated a policy of promoting immigration and religious tolerance.[40] With the Edict of Potsdam in 1685, Frederick William offered asylum to the French Huguenots.[41]

By 1700, approximately 30 percent of Berlin's residents were French, because of the Huguenot immigration.[42] Many other immigrants came from Bohemia, Poland, and Salzburg.[43]

Since 1618, the Margraviate of Brandenburg had been in personal union with the Duchy of Prussia. In 1701, the dual state formed the Kingdom of Prussia, as Frederick III, Elector of Brandenburg, crowned himself as king Frederick I in Prussia. Berlin became the capital of the new Kingdom,[44] replacing Königsberg. This was a successful attempt to centralise the capital in the very far-flung state, and it was the first time the city began to grow. In 1709, Berlin merged with the four cities of Cölln, Friedrichswerder, Friedrichstadt and Dorotheenstadt under the name Berlin, "Haupt- und Residenzstadt Berlin".[35] Between 1700 and 1750, Berlin’s population nearly quadrupled, rising from about 30,000 to 113,000.

In 1740, Frederick II, known as Frederick the Great (1740–1786), came to power.[45] Under the rule of Frederick II, Berlin became a center of the Enlightenment, but also, was briefly occupied during the Seven Years' War by the Russian army.[46] Following France's victory in the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte marched into Berlin in 1806, but granted self-government to the city.[47] In 1815, the city became part of the new Province of Brandenburg.[48]

The Industrial Revolution transformed Berlin during the 19th century; the city's economy and population expanded dramatically, and it became the main railway hub and economic center of Germany. Additional suburbs soon developed and increased the area and population of Berlin. In 1861, neighboring suburbs including Wedding, Moabit and several others were incorporated into Berlin.[49] In 1871, Berlin became capital of the newly founded German Empire.[50] In 1881, it became a city district separate from Brandenburg.[51]

20th to 21st centuries

[edit]In the early 20th century, Berlin had become a fertile ground for the German Expressionist movement.[52] In fields such as architecture, painting and cinema new forms of artistic styles were invented. At the end of World War I in 1918, a republic was proclaimed by Philipp Scheidemann at the Reichstag building. In 1920, the Greater Berlin Act incorporated dozens of suburban cities, villages, and estates around Berlin into an expanded city. The act increased the area of Berlin from 66 to 883 km2 (25 to 341 sq mi). The population almost doubled, and Berlin had a population of around four million. During the Weimar era, Berlin underwent political unrest due to economic uncertainties but also became a renowned center of the Roaring Twenties. The metropolis experienced its heyday as a major world capital and was known for its leadership roles in science, technology, arts, the humanities, city planning, film, higher education, government, and industries. Albert Einstein rose to public prominence during his years in Berlin,[53] being awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1921.[54]

In 1933, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power. Hitler was inspired by the architecture he had experienced in Vienna, and he wished for a German Empire with a capital city that had a monumental ensemble. The National Socialist regime embarked on monumental construction projects in Berlin as a way to express their power and authority through architecture. Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer developed architectural concepts for the conversion of the city into World Capital Germania; these were never implemented.[55]

NSDAP rule diminished Berlin's Jewish community from 160,000 (one-third of all Jews in the country) to about 80,000 due to emigration between 1933 and 1939. After Kristallnacht in 1938, thousands of the city's Jews were imprisoned in the nearby Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Starting in early 1943, many were deported to ghettos like Łódź, and to concentration and extermination camps such as Auschwitz.[56]

Berlin hosted the 1936 Summer Olympics for which the Olympic stadium was built.[57]

During World War II, Berlin was the location of multiple Nazi prisons, forced labor camps, 17 subcamps of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp for men and women, including teenagers, of various nationalities, including Polish, Jewish, French, Belgian, Czechoslovak, Russian, Ukrainian, Romani, Dutch, Greek, Norwegian, Spanish, Luxemburgish, German, Austrian, Italian, Yugoslavian, Bulgarian, Hungarian,[58] a camp for Sinti and Romani people (see Romani Holocaust),[59] and the Stalag III-D prisoner-of-war camp for Allied POWs of various nationalities.

During World War II, large parts of Berlin were destroyed during 1943–45 Allied air raids and the 1945 Battle of Berlin. The Allies dropped 67,607 tons of bombs on the city, destroying 6,427 acres of the built-up area. Around 125,000 civilians were killed.[60] After the end of World War II in Europe in May 1945, Berlin received large numbers of refugees from the Eastern provinces. The victorious powers divided the city into four sectors, analogous to Allied-occupied Germany the sectors of the Allies of World War II (the United States, the United Kingdom, and France) formed West Berlin, while the Soviet Union formed East Berlin.[61]

All four Allies of World War II shared administrative responsibilities for Berlin. However, in 1948, when the Western Allies extended the currency reform in the Western zones of Germany to the three western sectors of Berlin, the Soviet Union imposed the Berlin Blockade on the access routes to and from West Berlin, which lay entirely inside Soviet-controlled territory. The Berlin airlift, conducted by the three western Allies, overcame this blockade by supplying food and other supplies to the city from June 1948 to May 1949.[62] In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany was founded in West Germany and eventually included all of the American, British and French zones, excluding those three countries' zones in Berlin, while the Marxist–Leninist German Democratic Republic was proclaimed in East Germany. West Berlin officially remained an occupied city, but it politically was aligned with the Federal Republic of Germany despite West Berlin's geographic isolation. Airline service to West Berlin was granted only to American, British and French airlines.

The founding of the two German states increased Cold War tensions. West Berlin was surrounded by East German territory, and East Germany proclaimed the Eastern part as its capital, a move the western powers did not recognize. East Berlin included most of the city's historic center. The West German government established itself in Bonn.[63] In 1961, East Germany began to build the Berlin Wall around West Berlin, and events escalated to a tank standoff at Checkpoint Charlie. West Berlin was now de facto a part of West Germany with a unique legal status, while East Berlin was de facto a part of East Germany. John F. Kennedy gave his "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech on 26 June 1963, in front of the Schöneberg city hall, located in the city's western part, underlining the US support for West Berlin.[64] Berlin was completely divided. Although it was possible for Westerners to pass to the other side through strictly controlled checkpoints, for most Easterners, travel to West Berlin or West Germany was prohibited by the government of East Germany. In 1971, a Four-Power Agreement guaranteed access to and from West Berlin by car or train through East Germany.[65]

In 1989, with the end of the Cold War and pressure from the East German population, the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November and was subsequently mostly demolished. Today, the East Side Gallery preserves a large portion of the wall. On 3 October 1990, the two parts of Germany were reunified as the Federal Republic of Germany, and Berlin again became a reunified city. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the city experienced significant urban development and still impacts urban planning decisions.[66]

Walter Momper, the mayor of West Berlin, became the first mayor of the reunified city in the interim.[67] City-wide elections in December 1990 resulted in the first "all Berlin" mayor being elected to take office in January 1991, with the separate offices of mayors in East and West Berlin expiring by that time, and Eberhard Diepgen (a former mayor of West Berlin) became the first elected mayor of a reunited Berlin.[68] On 18 June 1994, soldiers from the United States, France and Britain marched in a parade which was part of the ceremonies to mark the withdrawal of allied occupation troops allowing a reunified Berlin[69] (the last Russian troops departed on 31 August, while the final departure of Western Allies forces was on 8 September 1994). On 20 June 1991, the Bundestag (German Parliament) voted to move the seat of the German capital from Bonn to Berlin, which was completed in 1999, during the chancellorship of Gerhard Schröder.[70]

Berlin's 2001 administrative reform merged several boroughs, reducing their number from 23 to 12.[71]

In 2006, the FIFA World Cup Final was held in Berlin.[72]

Construction of the "Berlin Wall Trail" (Berliner Mauerweg) began in 2002 and was completed in 2006.

In a 2016 terrorist attack linked to ISIL, a truck was deliberately driven into a Christmas market next to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, leaving 13 people dead and 55 others injured.[73][74]

In 2018, more than 200,000 protestors took to the streets in Berlin with demonstrations of solidarity against racism, in response to the emergence of far-right politics in Germany.[75]

Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER) opened in 2020, nine years later than planned, with Terminal 1 coming into service at the end of October, and flights to and from Tegel Airport ending in November.[76] Due to the fall in passenger numbers resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, plans were announced to close BER's Terminal 5, the former Schönefeld Airport, beginning in March 2021.[77] The connecting link of U-Bahn line U5 from Alexanderplatz to Hauptbahnhof, along with the new stations Rotes Rathaus and Unter den Linden, opened on 4 December 2020, the Museumsinsel U-Bahn station opened in 2021, which completed all new works on the U5.[78]

A partial opening by the end of 2020 of the Humboldt Forum museum, housed in the reconstructed Berlin Palace, was postponed until March 2021.[79] On 16 September 2022, the opening of the eastern wing, the last section of the Humboldt Forum museum, meant the Humboldt Forum museum was finally completed. It became Germany's currently most expensive cultural project.[80]

Berlin-Brandenburg fusion attempt

[edit]

The legal basis for a combined state of Berlin and Brandenburg is different from other state fusion proposals. Normally, Article 29 of the Basic Law stipulates that a state fusion requires a federal law.[81] However, a clause added to the Basic Law in 1994, Article 118a, allows Berlin and Brandenburg to unify without federal approval, requiring a referendum and a ratification by both state parliaments.[82]

In 1996, there was an unsuccessful attempt of unifying the states of Berlin and Brandenburg.[83] Both share a common history, dialect and culture and in 2020, there are over 225,000 residents of Brandenburg that commute to Berlin. The fusion had the near-unanimous support by a broad coalition of both state governments, political parties, media, business associations, trade unions and churches.[84] Though Berlin voted in favor by a small margin, largely based on support in former West Berlin, Brandenburg voters disapproved of the fusion by a large margin. It failed largely due to Brandenburg voters not wanting to take on Berlin's large and growing public debt and fearing losing identity and influence to the capital.[83]

Geography

[edit]Topography

[edit]

Berlin is in northeastern Germany, in an area of low-lying marshy woodlands with a mainly flat topography, part of the vast Northern European Plain which stretches all the way from northern France to western Russia. The Berliner Urstromtal (an ice age glacial valley), between the low Barnim Plateau to the north and the Teltow plateau to the south, was formed by meltwater flowing from ice sheets at the end of the last Weichselian glaciation. The Spree follows this valley now. In Spandau, a borough in the west of Berlin, the Spree empties into the river Havel, which flows from north to south through western Berlin. The course of the Havel is more like a chain of lakes, the largest being the Tegeler See and the Großer Wannsee. A series of lakes also feeds into the upper Spree, which flows through the Großer Müggelsee in eastern Berlin.[85]

Substantial parts of present-day Berlin extend onto the low plateaus on both sides of the Spree Valley. Large parts of the boroughs Reinickendorf and Pankow lie on the Barnim Plateau, while most of the boroughs of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, Steglitz-Zehlendorf, Tempelhof-Schöneberg, and Neukölln lie on the Teltow Plateau.

The borough of Spandau lies partly within the Berlin Glacial Valley and partly on the Nauen Plain, which stretches to the west of Berlin. Since 2015, the Arkenberge hills in Pankow at 122 meters (400 ft) elevation, have been the highest point in Berlin. Through the disposal of construction debris they surpassed Teufelsberg (120.1 m or 394 ft), which itself was made up of rubble from the ruins of the Second World War.[86] The Müggelberge at 114.7 meters (376 ft) elevation is the highest natural point and the lowest is the Spektesee in Spandau, at 28.1 meters (92 ft) elevation.[87]

Climate

[edit]Berlin has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb)[88] bordering on a humid continental climate (Dfb). This type of climate features mild to very warm summer temperatures and cold, though not very severe, winters. Annual precipitation is modest.[89][90]

Frosts are common in winter, and there are larger temperature differences between seasons than typical for many oceanic climates. Summers are warm and sometimes humid with average high temperatures of 22–25 °C (72–77 °F) and lows of 12–14 °C (54–57 °F). Winters are cold with average high temperatures of 3 °C (37 °F) and lows of −2 to 0 °C (28 to 32 °F). Spring and autumn are generally chilly to mild. Berlin's built-up area creates a microclimate, with heat stored by the city's buildings and pavement. Temperatures can be 4 °C (7 °F) higher in the city than in the surrounding areas.[91] Annual precipitation is 570 millimeters (22 in) with moderate rainfall throughout the year. Snowfall mainly occurs from December through March.[92] The hottest month in Berlin was July 1757, with a mean temperature of 23.9 °C (75.0 °F), and the coldest was January 1709, with a mean temperature of −13.2 °C (8.2 °F).[93] The wettest month on record was July 1907, with 230 millimeters (9.1 in) of rainfall, whereas the driest were October 1866, November 1902, October 1908 and September 1928, all with 1 millimeter (0.039 in) of rainfall.[94]

| Climate data for Berlin (Brandenburg), 1991–2020, extremes 1957–2024 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.1 (59.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.8 (87.4) |

32.7 (90.9) |

38.4 (101.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.0 (100.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

38.4 (101.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.4 (83.1) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.7 (90.9) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

34.8 (94.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

4.9 (40.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

4.1 (39.4) |

14.2 (57.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

1.6 (34.9) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

5.3 (41.6) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −12.0 (10.4) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.3 (−13.5) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

4.6 (40.3) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−24.0 (−11.2) |

−25.3 (−13.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 41.5 (1.63) |

30.0 (1.18) |

35.9 (1.41) |

27.7 (1.09) |

52.8 (2.08) |

60.2 (2.37) |

70.0 (2.76) |

52.4 (2.06) |

43.6 (1.72) |

40.3 (1.59) |

38.8 (1.53) |

39.1 (1.54) |

532.3 (20.96) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.8 | 13.9 | 14 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 12.4 | 13.4 | 12.7 | 11.6 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 16.4 | 162 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 8.4 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 4.9 | 24.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 85.9 | 81.2 | 75.8 | 67.2 | 66.9 | 66.3 | 67 | 68.5 | 76 | 82.7 | 87.8 | 87.5 | 76.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 52.6 | 77.9 | 126.7 | 196.4 | 231.1 | 232.9 | 233.7 | 222.2 | 168.9 | 113.8 | 57.4 | 45.0 | 1,758.6 |

| Source 1: Data derived from Deutscher Wetterdienst[95] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NCEI(days with precipitation and snow, humidity)[96] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Berlin (Dahlem), 58 m or 190 ft, 1961–1990 normals, extremes 1908–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

30.9 (87.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

36.1 (97.0) |

37.9 (100.2) |

37.7 (99.9) |

34.2 (93.6) |

27.5 (81.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.4 (31.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

1.2 (34.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

5.0 (41.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −21.0 (−5.8) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−16.5 (2.3) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

5.4 (41.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−20.2 (−4.4) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43.0 (1.69) |

37.0 (1.46) |

38.0 (1.50) |

42.0 (1.65) |

55.0 (2.17) |

71.0 (2.80) |

53.0 (2.09) |

65.0 (2.56) |

46.0 (1.81) |

36.0 (1.42) |

50.0 (1.97) |

55.0 (2.17) |

591 (23.29) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 112 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 45.4 | 72.3 | 122.0 | 157.7 | 221.6 | 220.9 | 217.9 | 210.2 | 156.3 | 110.9 | 52.4 | 37.4 | 1,625 |

| Source 1: NOAA[97] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Berliner Extremwerte[98] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape and architecture

[edit]Cityscape

[edit]

Berlin's history has left the city with a polycentric metropolitan area and an eclectic mix of architecture. The city's appearance today has been predominantly shaped by German history during the 20th century. 17% of Berlin's buildings are Gründerzeit or earlier and nearly 25% are of the 1920s and 1930s, when Berlin played a part in the origin of modern architecture.[99][100]

Devastated by the bombing of Berlin in World War II many of the buildings that had survived in both East and West were demolished during the postwar period. After the reunification, many important heritage structures have been reconstructed, including the Forum Fridericianum along with, the Berlin State Opera, Charlottenburg Palace, Gendarmenmarkt, Alte Kommandantur, as well as the City Palace.

The tallest buildings in Berlin are spread across the urban area, with clusters at Potsdamer Platz, City West, and Alexanderplatz.

Over one-third of the city's area consists of green and open-space,[13] with the Großer Tiergarten, one of the largest and most popular parks in Berlin, located in the centre of the city.

Architecture

[edit]

The Fernsehturm (TV tower) at Alexanderplatz in Mitte is among the tallest structures in the European Union at 368 m (1,207 ft). Built in 1969, it is visible throughout most of the central districts of Berlin. The city can be viewed from its 204-meter-high (669 ft) observation floor. Starting here, the Karl-Marx-Allee heads east, an avenue lined by monumental residential buildings, designed in the Socialist Classicism style. Adjacent to this area is the Rotes Rathaus (City Hall), with its distinctive red-brick architecture. In front of it is the Neptunbrunnen, a fountain featuring a mythological group of Tritons, personifications of the four main Prussian rivers, and Neptune on top of it. Nearby is the Nikolaiviertel, the reconstructed oldest settlement area in the city.

The Brandenburg Gate is an iconic landmark of Berlin and Germany; it stands as a symbol of eventful European history and of unity and peace. The Reichstag building is the traditional seat of the German Parliament. It was remodeled by British architect Norman Foster in the 1990s and features a glass dome over the session area, which allows free public access to the parliamentary proceedings and magnificent views of the city.

The East Side Gallery is an open-air exhibition of art painted directly on the last existing portions of the Berlin Wall. It is the largest remaining evidence of the city's historical division.

The Gendarmenmarkt is a neoclassical square in Berlin, the name of which derives from the headquarters of the famous Gens d'armes regiment located here in the 18th century. Two similarly designed cathedrals border it, the Französischer Dom with its observation platform and the Deutscher Dom. The Konzerthaus (Concert Hall), home of the Berlin Symphony Orchestra, stands between the two cathedrals.

The Museum Island in the River Spree houses five museums built from 1830 to 1930 and is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Restoration and construction of a main entrance to all museums (James Simon Gallery), as well as reconstruction of the Berlin Palace (Stadtschloss) were completed.[101][102] Also on the island and next to the Lustgarten and palace is Berlin Cathedral, emperor William II's ambitious attempt to create a Protestant counterpart to St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. A large crypt houses the remains of some of the earlier Prussian royal family. St. Hedwig's Cathedral is Berlin's Roman Catholic cathedral.

Unter den Linden is a tree-lined east–west avenue from the Brandenburg Gate to the Berlin Palace, and was once Berlin's premier promenade. Many Classical buildings line the street, and part of Humboldt University is there. Friedrichstraße was Berlin's legendary street during the Golden Twenties. It combines 20th-century traditions with the modern architecture of today's Berlin.

Potsdamer Platz is an entire quarter built from scratch after the Wall came down.[103] To the west of Potsdamer Platz is the Kulturforum, which houses the Gemäldegalerie, and is flanked by the Neue Nationalgalerie and the Berliner Philharmonie. The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, a Holocaust memorial, is to the north.[104]

The area around Hackescher Markt is home to fashionable culture, with countless clothing outlets, clubs, bars, and galleries. This includes the Hackesche Höfe, a conglomeration of buildings around several courtyards, reconstructed around 1996. The nearby New Synagogue is the center of Jewish culture.

The Straße des 17. Juni, connecting the Brandenburg Gate and Ernst-Reuter-Platz, serves as the central east–west axis. Its name commemorates the uprisings in East Berlin of 17 June 1953. Approximately halfway from the Brandenburg Gate is the Großer Stern, a circular traffic island on which the Siegessäule (Victory Column) is situated. This monument, built to commemorate Prussia's victories, was relocated in 1938–39 from its previous position in front of the Reichstag.

The Kurfürstendamm is home to some of Berlin's luxurious stores with the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church at its eastern end on Breitscheidplatz. The church was destroyed in the Second World War and left in ruins. Nearby on Tauentzienstraße is KaDeWe, claimed to be continental Europe's largest department store. The Rathaus Schöneberg, where John F. Kennedy made his famous "Ich bin ein Berliner!" speech, is in Tempelhof-Schöneberg.

West of the center, Bellevue Palace is the residence of the German President. Charlottenburg Palace, which was burnt out in the Second World War, is the largest historical palace in Berlin.

The Funkturm Berlin is a 150-meter-tall (490 ft) lattice radio tower in the fairground area, built between 1924 and 1926. It is the only observation tower which stands on insulators and has a restaurant 55 m (180 ft) and an observation deck 126 m (413 ft) above ground, which is reachable by a windowed elevator.

The Oberbaumbrücke over the Spree river is Berlin's most iconic bridge, connecting the now-combined boroughs of Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg. It carries vehicles, pedestrians, and the U1 Berlin U-Bahn line. The bridge was completed in a brick gothic style in 1896, replacing the former wooden bridge with an upper deck for the U-Bahn. The center portion was demolished in 1945 to stop the Red Army from crossing. After the war, the repaired bridge served as a checkpoint and border crossing between the Soviet and American sectors, and later between East and West Berlin. In the mid-1950s, it was closed to vehicles, and after the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, pedestrian traffic was heavily restricted. Following German reunification, the center portion was reconstructed with a steel frame, and U-Bahn service resumed in 1995.

Demographics

[edit]

At the end of 2023 the city-state of Berlin had 3.66 million registered inhabitants,[5] in an area of 891.3 km2 (344.1 sq mi).[3] Berlin is the most populous city proper in the European Union. In 2021, the urban area of Berlin had a population of over 4.6 million inhabitants.[6] As of 2019[update], the functional urban area was home to about 5.2 million people.[105] The entire Berlin-Brandenburg capital region has a population of more than 6 million in an area of 30,546 km2 (11,794 sq mi).[106][3]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1721 | 65,300 | — |

| 1750 | 113,289 | +73.5% |

| 1800 | 172,132 | +51.9% |

| 1815 | 197,717 | +14.9% |

| 1825 | 220,277 | +11.4% |

| 1840 | 330,230 | +49.9% |

| 1852 | 438,958 | +32.9% |

| 1861 | 547,571 | +24.7% |

| 1871 | 826,341 | +50.9% |

| 1880 | 1,122,330 | +35.8% |

| 1890 | 1,578,794 | +40.7% |

| 1900 | 1,888,848 | +19.6% |

| 1910 | 2,071,257 | +9.7% |

| 1920 | 3,879,409 | +87.3% |

| 1925 | 4,082,778 | +5.2% |

| 1933 | 4,221,024 | +3.4% |

| 1939 | 4,330,640 | +2.6% |

| 1945 | 3,064,629 | −29.2% |

| 1950 | 3,336,026 | +8.9% |

| 1960 | 3,274,016 | −1.9% |

| 1970 | 3,208,719 | −2.0% |

| 1980 | 3,048,759 | −5.0% |

| 1990 | 3,433,695 | +12.6% |

| 2000 | 3,388,434 | −1.3% |

| 2011 | 3,292,365 | −2.8% |

| 2022 | 3,596,999 | +9.3% |

| Population size may be affected by changes in administrative divisions. | ||

In 2014, the city-state Berlin had 37,368 live births (+6.6%), a record number since 1991. The number of deaths was 32,314. Almost 2 million households were counted in the city, of which 54 percent were inhabited by a single person. More than 337,000 families with children under the age of 18 lived in Berlin. In 2014, the German capital registered a migration surplus of approximately 40,000 people.[107]

Nationalities

[edit]

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| 2,931,731 | |

| 107,022 | |

| 62,495 | |

| 54,099 | |

| 48,301 | |

| 37,815 | |

| 33,732 | |

| 33,257 | |

| 33,256 | |

| 28,843 | |

| 25,851 | |

| 22,172 | |

| 21,743 | |

| 21,305 | |

| 19,484 |

National and international migration into the city has a long history. In 1685, after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in France, the city responded with the Edict of Potsdam, which guaranteed religious freedom and tax-free status to French Huguenot refugees for ten years. The Greater Berlin Act in 1920 incorporated many suburbs and surrounding cities of Berlin. It formed most of the territory that comprises modern Berlin and increased the population from 1.9 million to 4 million.

Active immigration and asylum politics in West Berlin triggered waves of immigration in the 1960s and 1970s. Berlin is home to at least 180,000 Turkish and Turkish German residents,[108] making it the largest Turkish community outside of Turkey.[109] In the 1990s the Aussiedlergesetze enabled immigration to Germany of some residents from the former Soviet Union. Today ethnic Germans from countries of the former Soviet Union make up the largest portion of the Russian-speaking community.[110] The last decade experienced an influx from various Western countries and some African regions.[111] A portion of the African immigrants have settled in the Afrikanisches Viertel.[112] Young Germans, EU-Europeans and Israelis have also settled in the city.[113]

In December 2019 there were 777,345 registered residents of foreign nationality and another 542,975 German citizens with a "migration background" (Migrationshintergrund, MH),[108] meaning they or one of their parents immigrated to Germany after 1955. Foreign residents of Berlin originate from about 190 countries.[114] 48 percent of the residents under the age of 15 have a migration background in 2017.[115] Berlin in 2009 was estimated to have 100,000 to 250,000 unregistered inhabitants.[116] Boroughs of Berlin with a significant number of migrants or foreign born population are Mitte, Neukölln and Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg.[117] The number of Arabic speakers in Berlin could be higher than 150,000. There are at least 40,000 Berliners with Syrian citizenship, third only behind Turkish and Polish citizens. The 2015 refugee crisis made Berlin Europe's capital of Arab culture.[118] Berlin is among the cities in Germany that have received the biggest amount of refugees after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. As of November 2022, an estimated 85,000 Ukrainian refugees were registered in Berlin,[119] making Berlin the most popular destination of Ukrainian refugees in Germany.[120]

Berlin has a vibrant expatriate community involving, among others, precarious immigrants, seasonal workers, and refugees. Therefore, Berlin sustains a broad variety of English-based speakers. Speaking a particular type of English does attract prestige and cultural capital in Berlin.[121]

Languages

[edit]German is the official and predominant spoken language in Berlin. It is a West Germanic language that derives most of its vocabulary from the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family. German is one of 24 languages of the European Union,[122] and one of the three working languages of the European Commission.

Berlinerisch or Berlinisch is not a dialect linguistically. It is spoken in Berlin and the surrounding metropolitan area. It originates from a Brandenburgish variant. The dialect is now seen more like a sociolect, largely through increased immigration and trends among the educated population to speak standard German in everyday life.

The most commonly spoken foreign languages in Berlin are Turkish, Polish, English, Persian, Arabic, Italian, Bulgarian, Russian, Romanian, Kurdish, Serbo-Croatian, French, Spanish and Vietnamese. Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish, and Serbo-Croatian are heard more often in the western part due to the large Middle Eastern and former-Yugoslavian communities. Polish, English, Russian, and Vietnamese have more native speakers in East Berlin.[123]

Religion

[edit]

- Not religious/other 72 (70.9%)

- EKD Protestants 15 (14.8%)

- Catholics 9 (8.87%)

- Islam 4 (3.94%)

- Jewish 1 (0.99%)

- Other 0.5 (0.49%)

On the report of the 2011 census, approximately 37 percent of the population reported being members of a legally-recognized church or religious organization. The rest either did not belong to such an organization, or there was no information available about them.[125]

The largest religious denomination recorded in 2010 was the Protestant regional church body—the Evangelical Church of Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia (EKBO)—a united church. EKBO is a member of the Protestant Church in Germany (EKD) and of the Union of Protestant Churches in the EKD (UEK). According to the EKBO, their membership accounted for 18.7 percent of the local population, while the Roman Catholic Church had 9.1 percent of residents registered as its members.[126] About 2.7% of the population identify with other Christian denominations (mostly Eastern Orthodox, but also various Protestants).[127] According to the Berlin residents register, in 2018 14.9 percent were members of the Evangelical Church, and 8.5 percent were members of the Catholic Church.[108] The government keeps a register of members of these churches for tax purposes, because it collects church tax on behalf of the churches. It does not keep records of members of other religious organizations which may collect their own church tax, in this way.

In 2009, approximately 249,000 Muslims were reported by the Office of Statistics to be members of mosques and Islamic religious organizations in Berlin,[128] while in 2016, the newspaper Der Tagesspiegel estimated that about 350,000 Muslims observed Ramadan in Berlin.[129] In 2019, about 437,000 registered residents, 11.6% of the total, reported having a migration background from one of the Member states of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.[108][129] Between 1992 and 2011 the Muslim population almost doubled.[130]

About 0.9% of Berliners belong to other religions. Of the estimated population of 30,000–45,000 Jewish residents,[131] approximately 12,000 are registered members of religious organizations.[127]

Berlin is the seat of the Roman Catholic archbishop of Berlin and EKBO's elected chairperson is titled the bishop of EKBO. Furthermore, Berlin is the seat of many Orthodox cathedrals, such as the Cathedral of St. Boris the Baptist, one of the two seats of the Bulgarian Orthodox Diocese of Western and Central Europe, and the Resurrection of Christ Cathedral of the Diocese of Berlin (Patriarchate of Moscow).

The faithful of the different religions and denominations maintain many places of worship in Berlin. The Independent Evangelical Lutheran Church has eight parishes of different sizes in Berlin.[132] There are 36 Baptist congregations (within Union of Evangelical Free Church Congregations in Germany), 29 New Apostolic Churches, 15 United Methodist churches, eight Free Evangelical Congregations, four Churches of Christ, Scientist (1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 11th), six congregations of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, an Old Catholic church, and an Anglican church in Berlin. Berlin has more than 80 mosques,[133] ten synagogues,[134] and two Buddhist as well as four Hindu temples.

Government and politics

[edit]German federal city state

[edit]Since the German reunification on 3 October 1990, Berlin has been one of the three city-states of Germany among the present 16 federal states of Germany. The Abgeordnetenhaus von Berlin (House of Representatives) functions as the city and state parliament, which has 141 seats. Berlin's executive body is the Senate of Berlin (Senat von Berlin). The Senate consists of the Governing Mayor of Berlin (Regierender Bürgermeister), and up to ten senators holding ministerial positions, two of them holding the title of "Mayor" (Bürgermeister) as deputy to the Governing Mayor.[135]

The total annual budget of Berlin in 2015 exceeded €24.5 ($30.0) billion including a budget surplus of €205 ($240) million.[136] The German Federal city state of Berlin owns extensive assets, including administrative and government buildings, real estate companies, as well as stakes in the Olympic Stadium, swimming pools, housing companies, and numerous public enterprises and subsidiary companies.[137][138] The federal state of Berlin runs a real estate portal to advertise commercial spaces or land suitable for redevelopment.[139]

The Social Democratic Party (SPD) and The Left (Die Linke) took control of the city government after the 2001 state election and won another term in the 2006 state election.[140] From the 2016 state election until the 2023 state election, there was a coalition between the Social Democratic Party, the Greens and the Left Party. Since April 2023, the government has been formed by a coalition between the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats.[141]

The Governing Mayor is simultaneously Lord Mayor of the City of Berlin (Oberbürgermeister der Stadt) and Minister President of the State of Berlin (Ministerpräsident des Bundeslandes). The office of the Governing Mayor is in the Rotes Rathaus (Red City Hall). Since 2023, this office has been held by Kai Wegner of the Christian Democrats.[141] He is the first conservative mayor in Berlin in more than two decades.[142]

Boroughs

[edit]

Berlin is subdivided into 12 boroughs or districts (Bezirke). Each borough has several subdistricts or neighborhoods (Ortsteile), which have roots in much older municipalities that predate the formation of Greater Berlin on 1 October 1920. These subdistricts became urbanized and incorporated into the city later on. Many residents strongly identify with their neighborhoods, colloquially called Kiez. At present, Berlin consists of 96 subdistricts, which are commonly made up of several smaller residential areas or quarters.[citation needed]

Each borough is governed by a borough council (Bezirksamt) consisting of five councilors (Bezirksstadträte) including the borough's mayor (Bezirksbürgermeister). The council is elected by the borough assembly (Bezirksverordnetenversammlung). However, the individual boroughs are not independent municipalities, but subordinate to the Senate of Berlin.[citation needed] The borough's mayors make up the council of mayors (Rat der Bürgermeister), which is led by the city's Governing Mayor and advises the Senate. The neighborhoods have no local government bodies.

City partnerships

[edit]Berlin to this day maintains official partnerships with 17 cities.[143] Town twinning between West Berlin and other cities began with its sister city Los Angeles, California, in 1967. East Berlin's partnerships were canceled at the time of German reunification.

Capital city

[edit]Berlin is the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany. The President of Germany, whose functions are mainly ceremonial under the German constitution, has their official residence in Bellevue Palace.[144] Berlin is the seat of the German Chancellor (Prime Minister), housed in the Chancellery building, the Bundeskanzleramt. Facing the Chancellery is the Bundestag, the German Parliament, housed in the renovated Reichstag building since the government's relocation to Berlin in 1998. The Bundesrat ("federal council", performing the function of an upper house) is the representation of the 16 constituent states (Länder) of Germany and has its seat at the former Prussian House of Lords. The total annual federal budget managed by the German government exceeded €310 ($375) billion in 2013.[145]

The relocation of the federal government and Bundestag to Berlin was mostly completed in 1999. However, some ministries, as well as some minor departments, stayed in the federal city Bonn, the former capital of West Germany. Discussions about moving the remaining ministries and departments to Berlin continue.[146]

The Federal Foreign Office and the ministries and departments of Defense, Justice and Consumer Protection, Finance, Interior, Economic Affairs and Energy, Labor and Social Affairs, Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, Food and Agriculture, Economic Cooperation and Development, Health, Transport and Digital Infrastructure and Education and Research are based in the capital.

Embassies

[edit]Berlin hosts in total 158 foreign embassies[147] as well as the headquarters of many think tanks, trade unions, nonprofit organizations, lobbying groups, and professional associations. Frequent official visits and diplomatic consultations among governmental representatives and national leaders are common in contemporary Berlin.

Economy

[edit]In 2018, the GDP of Berlin totaled €147 billion, an increase of 3.1% over the previous year.[3] Berlin's economy is dominated by the service sector, with around 84% of all companies doing business in services. In 2015, the total labor force in Berlin was 1.85 million. The unemployment rate reached a 24-year low in November 2015 and stood at 10.0%.[148] From 2012 to 2015 Berlin, as a German state, had the highest annual employment growth rate. Around 130,000 jobs were added in this period.[149] In 2025, about 330,000 people in Berlin received unemployment payments.[150]

Important economic sectors in Berlin include life sciences, transportation, information and communication technologies, media and music, advertising and design, biotechnology, environmental services, construction, e-commerce, retail, hotel business, and medical engineering.[151]

Research and development have economic significance for the city.[152] Several major corporations like Volkswagen, Pfizer, and SAP operate innovation laboratories in the city.[153] The Science and Business Park in Adlershof is the largest technology park in Germany measured by revenue.[154] Within the eurozone, Berlin has become a center for business relocation and international investments.[155]

| Year[156] | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate in % | 13.6 | 13.3 | 12.3 | 11.7 | 11.1 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 8.6 | 9.1 |

Companies

[edit]Many German and international companies have business or service centers in the city. For several years Berlin has been recognized as a major center of business founders.[158] In 2015, Berlin generated the most venture capital for young startup companies in Europe.[159]

Among the 10 largest employers in Berlin are the City-State of Berlin, Deutsche Bahn, largest railway company in the world,[157] the hospital providers Charité and Vivantes, the Federal Government of Germany, the local public transport provider BVG, Siemens and Deutsche Telekom.[160]

Siemens, a Global 500 and DAX-listed company is partly headquartered in Berlin. Other DAX-listed companies headquartered in Berlin are the property company Deutsche Wohnen and the online food delivery service Delivery Hero. The national railway operator Deutsche Bahn,[161] Europe's largest digital publisher[162] Axel Springer as well as the MDAX-listed firms Zalando and HelloFresh and also have their main headquarters in the city. Among the largest international corporations who have their German or European headquarters in Berlin are Bombardier Transportation, Securing Energy for Europe, Coca-Cola, Pfizer, Sony and TotalEnergies.

As of 2023, Sparkassen-Finanzgruppe, a network of public banks that together form the largest financial services group in Germany and in all of Europe, is headquartered in Berlin. The Bundesverband der Deutschen Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken has its headquarters in Berlin, managing around 1.200 trillion euros.[163] The three largest banks in the capital are Deutsche Kreditbank, Landesbank Berlin and Berlin Hyp.[164]

Mercedes-Benz Group manufactures cars, and BMW builds motorcycles in Berlin. In 2022, American electric car manufacturer Tesla opened its first European Gigafactory outside the city borders in Grünheide (Mark), Brandenburg. The Pharmaceuticals division of Bayer[165] and Berlin Chemie are major pharmaceutical companies in the city.

Tourism and conventions

[edit]Berlin had 788 hotels with 134,399 beds in 2014.[166] The city recorded 28.7 million overnight hotel stays and 11.9 million hotel guests in 2014.[166] Tourism figures have more than doubled within the last ten years and Berlin has become the third-most-visited city destination in Europe. Some of the most visited places in Berlin include: Potsdamer Platz, Brandenburger Tor, the Berlin wall, Alexanderplatz, Museumsinsel, Fernsehturm, the East-Side Gallery, Schloss-Charlottenburg, Zoologischer Garten, Siegessäule, Gedenkstätte Berliner Mauer, Mauerpark, Botanical Garden, Französischer Dom, Deutscher Dom and Holocaust-Mahnmal. The largest visitor groups are from Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and the United States.[citation needed]

According to figures from the International Congress and Convention Association in 2015, Berlin became the leading organizer of conferences globally, hosting 195 international meetings.[167] Some of these congress events take place on venues such as CityCube Berlin or the Berlin Congress Center (bcc).

The Messe Berlin (also known as Berlin ExpoCenter City) is the main convention organizing company in the city. Its main exhibition area covers more than 160,000 square meters (1,722,226 sq ft). Several large-scale trade fairs like the consumer electronics trade fair IFA, where the first practical audio tape recorder and the first completely electronic television system were first introduced to the public,[168][169][170][171] the ILA Berlin Air Show, the Berlin Fashion Week (including the Premium Berlin and the Panorama Berlin),[172] the Green Week, the Fruit Logistica, the transport fair InnoTrans, the tourism fair ITB and the adult entertainment and erotic fair Venus are held annually in the city, attracting a significant number of business visitors.

Creative industries

[edit]

The creative arts and entertainment business is an important part of Berlin's economy. The sector comprises music, film, advertising, architecture, art, design, fashion, performing arts, publishing, R&D, software,[174] TV, radio, and video games.

In 2014, around 30,500 creative companies operated in the Berlin-Brandenburg metropolitan region, predominantly SMEs. Generating a revenue of 15.6 billion Euro and 6% of all private economic sales, the culture industry grew from 2009 to 2014 at an average rate of 5.5% per year.[175]

Berlin is an important European and German film industry hub.[176] It is home to more than 1,000 film and television production companies, 270 movie theaters, and around 300 national and international co-productions are filmed in the region every year.[152] The historic Babelsberg Studios and the production company UFA are adjacent to Berlin in Potsdam. The city is also home of the German Film Academy (Deutsche Filmakademie), founded in 2003, and the European Film Academy, founded in 1988.

Media

[edit]

Berlin is home to many magazine, newspaper, book, and scientific/academic publishers and their associated service industries. In addition, around 20 news agencies, more than 90 regional daily newspapers and their websites, as well as the Berlin offices of more than 22 national publications such as Der Spiegel, and Die Zeit reinforce the capital's position as Germany's epicenter for influential debate. Therefore, many international journalists, bloggers, and writers live and work in the city.[citation needed]

Berlin is the central location to several international and regional television and radio stations.[177] The public broadcaster RBB has its headquarters in Berlin as well as the commercial broadcasters MTV Europe and Welt. German international public broadcaster Deutsche Welle has its TV production unit in Berlin, and most national German broadcasters have a studio in the city, including ZDF and RTL.

Berlin has Germany's largest number of daily newspapers, with numerous local broadsheets (Berliner Morgenpost, Berliner Zeitung, Der Tagesspiegel), and three major tabloids, as well as national dailies of varying sizes, each with a different political affiliation, such as Die Welt, Neues Deutschland, and Die Tageszeitung. The Berliner, a monthly magazine, is Berlin's English-language periodical and La Gazette de Berlin a French-language newspaper.[citation needed]

Berlin is also the headquarter of major German-language publishing houses like Walter de Gruyter, Springer, the Ullstein Verlagsgruppe (publishing group), Suhrkamp, and Cornelsen are all based in Berlin. Each of which publishes books, periodicals, and multimedia products.[citation needed]

Quality of life

[edit]According to Mercer, Berlin ranked number 19 in the Quality of Living City Ranking in 2024.[178]

Also in 2024, according to Monocle, Berlin occupied the position of the 17th-most-livable city in the world.[179] Economist Intelligence Unit ranked Berlin number 21 of all global cities for livability.[180] In 2019 Berlin was also number 8 on the Global Power City Index.[181] In the same year Berlin was honored for having the best future prospects of all cities in Germany.[182]

Transport

[edit]Roads

[edit]Berlin's transport infrastructure provides a diverse range of urban mobility.[183]

A total of 979 bridges cross 197 km (122 miles) the inner-city waterways. Berlin roads total 5,422 km (3,369 miles) of which 77 km (48 miles) are motorways (known as Autobahn).[184] In 2013 only 1.344 million motor vehicles were registered in the city.[184] With 377 cars per 1000 residents in 2013 (570/1000 in Germany), Berlin as a Western global city has one of the lowest numbers of cars per capita.[185]

Cycling

[edit]

Berlin is well known for its highly developed bicycle lane system.[186] It is estimated that Berlin has 710 bicycles per 1,000 residents. Around 500,000 daily bike riders accounted for 13 percent of total traffic in 2010.[187]

Cyclists in Berlin have access to 620 km of bicycle paths including approximately 150 km of mandatory bicycle paths, 190 km of off-road bicycle routes, 60 km of bicycle lanes on roads, 70 km of shared bus lanes which are also open to cyclists, 100 km of combined pedestrian/bike paths and 50 km of marked bicycle lanes on roadside pavements or sidewalks.[188] Riders are allowed to carry their bicycles on Regionalbahn (RE), S-Bahn and U-Bahn trains, on trams, and on night buses if a bike ticket is purchased.[189]

Taxicabs

[edit]

Taxicabs in Berlin are yellow or beige. In 2024, around 8,000 taxicabs were in service.[190] Like in most of Europe, app-based sharing cab services are available but limited.[191]

Rail

[edit]

Long-distance rail lines directly connect Berlin with all of the major cities of Germany. the regional rail lines of the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg provide access to Brandenburg and to the Baltic Sea. The Berlin Hauptbahnhof (Berlin Central Station) is the largest grade-separated railway station in Europe.[192] The Deutsche Bahn runs the high speed Intercity-Express (ICE) to domestic destinations, including Hamburg, Munich, Cologne, Stuttgart, and Frankfurt am Main.

Water transport

[edit]The Spree and the Havel rivers cross Berlin. There are no frequent passenger connections to and from Berlin by water. Berlin's largest inland port, the Westhafen, is located in the district of Moabit. It is a transhipment and storage site for inland shipping with a growing importance.[193]

Intercity buses

[edit]There is an increasing quantity of intercity bus services. Berlin city has more than 10 stations[194] that run buses to destinations throughout Berlin. Destinations in Germany and Europe are connected via the intercity bus exchange Zentraler Omnibusbahnhof Berlin.

Urban public transport

[edit]

The Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) and the German State-owned Deutsche Bahn (DB) manage several extensive urban public transport systems.[195]

| System | Stations / Lines / Net length | Annual ridership | Operator / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Bahn | 166 / 16 / 331 km (206 mi) | 431,000,000 (2016) | DB / Mainly overground rapid transit rail system with suburban stops |

| U-Bahn | 173 / 9 / 146 km (91 mi) | 563,000,000 (2017) | BVG / Mainly underground rail system / 24h-service on weekends |

| Tram | 404 / 22 / 194 km (121 mi) | 197,000,000 (2017) | BVG / Operates predominantly in eastern boroughs |

| Bus | 3227 / 198 / 1,675 km (1,041 mi) | 440,000,000 (2017) | BVG / Extensive services in all boroughs / 62 Night Lines |

| Ferry | 6 lines | BVG / Transportation as well as recreational ferries |

Public transport in Berlin has a long and complicated history because of the 20th-century division of the city, where movement between the two halves was not served. Since 1989, the transport network has been developed extensively. However, it still contains early 20th century traits, such as the U1.[196]

Airports

[edit]

Berlin is served by one commercial international airport: Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), located just outside Berlin's south-eastern border, in the state of Brandenburg. It began construction in 2006, with the intention of replacing Tegel Airport (TXL) and Schönefeld Airport (SXF) as the single commercial airport of Berlin.[197] Previously set to open in 2012, after extensive delays and cost overruns, it opened for commercial operations in October 2020.[198] The planned initial capacity of around 27 million passengers per year[199] is to be further developed to bring the terminal capacity to approximately 55 million per year by 2040.[200]

Before the opening of the BER in Brandenburg, Berlin was served by Tegel Airport and Schönefeld Airport. Tegel Airport was within the city limits, and Schönefeld Airport was located at the same site as BER. Both airports together handled 29.5 million passengers in 2015. In 2014, 67 airlines served 163 destinations in 50 countries from Berlin.[201] Tegel Airport was a focus city for Lufthansa and Eurowings while Schönefeld served as an important destination for airlines like Germania, easyJet and Ryanair. Until 2008, Berlin was also served by the smaller Tempelhof Airport, which functioned as a city airport, with a convenient location near the city center, allowing for quick transit times between the central business district and the airport. The airport grounds have since been turned into a city park.[citation needed]

Rohrpost

[edit]From 1865 to 1976, Berlin operated an expansive pneumatic postal network, reaching a maximum length of 400 kilometers (roughly 250 miles) by 1940. The system was divided into two distinct networks after 1949. The West Berlin system remained in public use until 1963, and continued to be utilized for government correspondence until 1972. Conversely, the East Berlin system, which incorporated the Hauptelegraphenamt—the central hub of the operation—remained functional until 1976.[citation needed]

Energy

[edit]

Berlin's two largest energy provider for private households are the Swedish firm Vattenfall and the Berlin-based company GASAG. Both offer electric power and natural gas supply. Some of the city's electric energy is imported from nearby power plants in southern Brandenburg.[202]

As of 2015[update] the five largest power plants measured by capacity are the Heizkraftwerk Reuter West, the Heizkraftwerk Lichterfelde, the Heizkraftwerk Mitte, the Heizkraftwerk Wilmersdorf, and the Heizkraftwerk Charlottenburg. All of these power stations generate electricity and useful heat at the same time to facilitate buffering during load peaks.

In 1993 the power grid connections in the Berlin-Brandenburg capital region were renewed. In most of the inner districts of Berlin power lines are underground cables; only a 380 kV and a 110 kV line, which run from Reuter substation to the urban Autobahn, use overhead lines. The Berlin 380-kV electric line is the backbone of the city's energy grid.

Health

[edit]

Berlin has a long history of discoveries in medicine and innovations in medical technology.[203] The modern history of medicine has been significantly influenced by scientists from Berlin. Rudolf Virchow was the founder of cellular pathology, while Robert Koch developed vaccines for anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis.[204] For his life's work Koch is seen as one of the founders of modern medicine.[205]

The Charité complex (Universitätsklinik Charité) is the largest university hospital in Europe, tracing back its origins to the year 1710. More than half of all German Nobel Prize winners in Physiology or Medicine, including Emil von Behring, Robert Koch and Paul Ehrlich, have worked at the Charité. The Charité is spread over four campuses and comprises around 3,000 beds, 15,500 staff, 8,000 students, and more than 60 operating theaters, and it has a turnover of two billion euros annually.[206]

Telecommunication

[edit]

Since 2017, the digital television standard in Berlin and Germany is DVB-T2. This system transmits compressed digital audio, digital video and other data in an MPEG transport stream.

Berlin has installed several hundred free public Wireless LAN sites across the capital since 2016. The wireless networks are concentrated mostly in central districts; 650 hotspots (325 indoor and 325 outdoor access points) are installed.[207]

The UMTS (3G) and LTE (4G) networks of the three major cellular operators Vodafone, Telekom Deutschland and O2 enable the use of mobile broadband applications citywide.

Education and research

[edit]

As of 2014[update], Berlin had 878 schools, teaching 340,658 students in 13,727 classes and 56,787 trainees in businesses and elsewhere.[152] The city has a 6-year primary education program. After completing primary school, students continue to the Sekundarschule (a comprehensive school) or Gymnasium (college preparatory school). Berlin has a special bilingual school program in the Europaschule, in which children are taught the curriculum in German and a foreign language, starting in primary school and continuing in high school.[209]

The Französisches Gymnasium Berlin, which was founded in 1689 to teach the children of Huguenot refugees, offers (German/French) instruction.[210] The John F. Kennedy School, a bilingual German–American public school in Zehlendorf, is particularly popular with children of diplomats and the English-speaking expatriate community. 82 Gymnasien teach Latin[211] and 8 teach Classical Greek.[212]

Higher education

[edit]

The Berlin-Brandenburg capital region is one of the most prolific centers of higher education and research in Germany and Europe. Historically, 67 Nobel Prize winners are affiliated with the Berlin-based universities.

The city has four public research universities and more than 30 private, professional, and technical colleges (Hochschulen), offering a wide range of disciplines.[213] A record number of 175,651 students were enrolled in the winter term of 2015/16.[214] Among them around 18% have an international background.

The three largest universities combined have approximately 103,000 enrolled students. There are the Freie Universität Berlin (Free University of Berlin, FU Berlin) with about 33,000[215] students, the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin (HU Berlin) with 35,000[216] students, and Technische Universität Berlin (TU Berlin) with 35,000[217] students. The Charité Medical School has around 8,000 students.[206] The FU, the HU, the TU, and the Charité make up the Berlin University Alliance, which has received funding from the Excellence Strategy program of the German government.[218][219] The Universität der Künste (UdK) has about 4,000 students and ESMT Berlin is only one of four business schools in Germany with triple accreditation.[220] The Hertie School, a private public policy school located in Mitte, has more than 900 students and doctoral students. The Berlin School of Economics and Law has an enrollment of about 11,000 students, the Berlin University of Applied Sciences and Technology of about 12,000 students, and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft (University of Applied Sciences for Engineering and Economics) of about 14,000 students.

Research

[edit]

The city has a high density of internationally renowned research institutions, such as the Fraunhofer Society, the DLR Institute for Planetary Research, the Leibniz Association, the Helmholtz Association, and the Max Planck Society, which are independent of, or only loosely connected to its universities.[221] In 2012, around 65,000 professional scientists were working in research and development in the city.[152]

Berlin is one of the knowledge and innovation communities (KIC) of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT).[222] The KIC is based at the Center for Entrepreneurship at TU Berlin and has a focus in the development of IT industries. It partners with major multinational companies such as Siemens, Deutsche Telekom, and SAP.[223]

One of Europe's successful research, business and technology clusters is based at WISTA in Berlin-Adlershof, with more than 1,000 affiliated firms, university departments and scientific institutions.[224]

In addition to the university-affiliated libraries, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin is a major research library. Its two main locations are on Potsdamer Straße and on Unter den Linden. There are also 86 public libraries in the city.[152] ResearchGate, a global social networking site for scientists, is based in Berlin.

Culture

[edit]

Berlin is known for its numerous cultural institutions, many of which enjoy international reputation.[28][225] The diversity and vivacity of the metropolis led to a trendsetting atmosphere.[226] An innovative music, dance and art scene has developed in the 21st century.

Young people, international artists and entrepreneurs continued to settle in the city and made Berlin a popular entertainment center in the world.[227]

The expanding cultural performance of the city was underscored by the relocation of the Universal Music Group who decided to move their headquarters to the banks of the River Spree.[228] In 2005, Berlin was named "City of Design" by UNESCO and has been part of the Creative Cities Network ever since.[229][25]

Many German and International films were shot in Berlin, including M, One, Two, Three, Cabaret, Christiane F., Possession, Octopussy, Wings of Desire, Run Lola Run, The Bourne Trilogy, Good Bye, Lenin!, The Lives of Others, Inglourious Basterds, Hanna, Unknown and Bridge of Spies.

Galleries and museums

[edit]

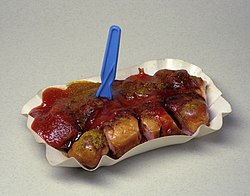

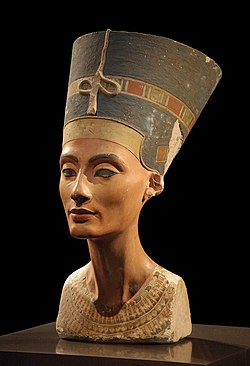

As of 2011[update] Berlin is home to 138 museums and more than 400 art galleries.[152][230] The ensemble on the Museum Island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is in the northern part of the Spree Island between the Spree and the Kupfergraben.[28] As early as 1841 it was designated a "district dedicated to art and antiquities" by a royal decree. Subsequently, the Altes Museum was built in the Lustgarten. The Neues Museum, which displays the bust of Queen Nefertiti,[231] Alte Nationalgalerie, Pergamon Museum, and Bode Museum were built there.

Apart from the Museum Island, there are many additional museums in the city. The Gemäldegalerie (Painting Gallery) focuses on the paintings of the "old masters" from the 13th to the 18th centuries, while the Neue Nationalgalerie (New National Gallery, built by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe) specializes in 20th-century European painting. The Hamburger Bahnhof, in Moabit, exhibits a major collection of modern and contemporary art. The expanded Deutsches Historisches Museum reopened in the Zeughaus with an overview of German history spanning more than a millennium. The Bauhaus Archive is a museum of 20th-century design from the famous Bauhaus school. Museum Berggruen houses the collection of noted 20th century collector Heinz Berggruen, and features an extensive assortment of works by Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, and Giacometti, among others.[232] The Kupferstichkabinett Berlin (Museum of Prints and Drawings) is part of the Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (Berlin State Museums) and the Kulturforum at Potsdamer Platz in the Tiergarten district of Berlin's Mitte district. It is the largest museum of the graphic arts in Germany and at the same time one of the four most important collections of its kind in the world.[233] The collection includes Friedrich Gilly's design for the monument to Frederick II of Prussia.[234]

The Jewish Museum has a standing exhibition on two millennia of German-Jewish history.[235] The German Museum of Technology in Kreuzberg has a large collection of historical technical artifacts. The Museum für Naturkunde (Berlin's natural history museum) exhibits natural history near Berlin Hauptbahnhof. It has the largest mounted dinosaur in the world (a Giraffatitan skeleton). A well-preserved specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex and the early bird Archaeopteryx are at display as well.[236]

In Dahlem, there are several museums of world art and culture, such as the Museum of Asian Art, the Ethnological Museum, the Museum of European Cultures, as well as the Allied Museum. The Brücke Museum features one of the largest collection of works by artist of the early 20th-century expressionist movement. In Lichtenberg, on the grounds of the former East German Ministry for State Security, is the Stasi Museum. The site of Checkpoint Charlie, one of the most renowned crossing points of the Berlin Wall, is still preserved. A private museum venture exhibits a comprehensive documentation of detailed plans and strategies devised by people who tried to flee from the East.

The Beate Uhse Erotic Museum claimed to be the largest erotic museum in the world until it closed in 2014.[237][238]

The cityscape of Berlin displays large quantities of urban street art.[239] It has become a significant part of the city's cultural heritage and has its roots in the graffiti scene of Kreuzberg of the 1980s.[240] The Berlin Wall itself has become one of the largest open-air canvasses in the world.[241] The leftover stretch along the Spree river in Friedrichshain remains as the East Side Gallery. Berlin today is consistently rated as an important world city for street art culture.[242] Berlin has galleries which are quite rich in contemporary art. Located in Mitte, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, KOW, Sprüth Magers; Kreuzberg there are a few galleries as well such as Blain Southern, Esther Schipper, Future Gallery, König Gallerie.

Nightlife and festivals

[edit]

Berlin's nightlife has been celebrated as one of the most diverse and vibrant of its kind.[243][244] In the 1970s and 80s, the SO36 in Kreuzberg was a center for punk music and culture. The SOUND and the Dschungel gained notoriety. Throughout the 1990s, people in their 20s from all over the world, particularly those in Western and Central Europe, made Berlin's club scene a premier nightlife venue. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, many historic buildings in Mitte, the former city center of East Berlin, were illegally occupied and re-built by young squatters and became a fertile ground for underground and counterculture gatherings.[245] The central boroughs are home to many nightclubs, including the Tresor and the Berghain. The KitKatClub and several other locations are known for their sexually uninhibited parties.

Clubs are not required to close at a fixed time during the weekends, and many parties last well into the morning or even all weekend, including near Alexanderplatz. Several venues have become a popular stage for the Neo-Burlesque scene.

Berlin has a long history of gay culture, and is an important birthplace of the LGBT rights movement. Same-sex bars and dance halls operated freely as early as the 1880s, and the first gay magazine, Der Eigene, started in 1896. By the 1920s, gays and lesbians had an unprecedented visibility.[246][247] Today, in addition to a positive atmosphere in the wider club scene, the city again has a huge number of queer clubs and festivals. The most famous and largest are Berlin Pride, the Christopher Street Day,[248] the Lesbian and Gay City Festival in Berlin-Schöneberg, the Kreuzberg Pride.

The annual Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) with around 500,000 admissions is considered to be the largest publicly attended film festival in the world.[249][250] The Karneval der Kulturen (Carnival of Cultures), a multi-ethnic street parade, is celebrated every Pentecost weekend.[251] Berlin is also well known for the cultural festival Berliner Festspiele, which includes the jazz festival JazzFest Berlin, and Young Euro Classic, the largest international festival of youth orchestras in the world. Several technology and media art festivals and conferences are held in the city, including Transmediale and Chaos Communication Congress. The annual Berlin Festival focuses on indie rock, electronic music and synthpop and is part of the International Berlin Music Week.[252][253] Every year Berlin hosts one of the largest New Year's Eve celebrations in the world, attended by well over a million people. The focal point is the Brandenburg Gate, where midnight fireworks are centered, but various private fireworks displays take place throughout the entire city. Partygoers in Germany often toast the New Year with a glass of sparkling wine.

Performing arts

[edit]