Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

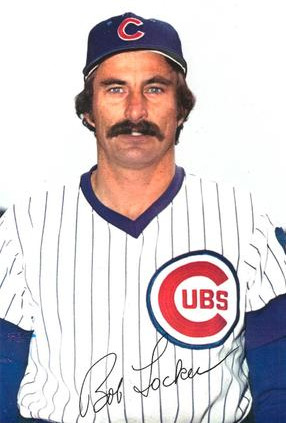

Bob Locker

View on Wikipedia

Robert Awtry Locker (March 15, 1938 – August 15, 2022) was an American Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher. He pitched from 1965 to 1975 for five different teams. The sinker-balling Locker never made a start in his big-league career.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Locker graduated from George High School in 1956, where he played baseball and basketball. He enrolled at Iowa State University, and made the varsity team in both sports. Locker graduated from ISU in 1960 with a Bachelor of Science degree in geology and was a member of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity. After graduation, he signed his first professional baseball contract, with the Chicago White Sox.[1]

Career

[edit]Minor Leagues (1960–61, 1964)

[edit]Locker began his professional career in 1960 at Idaho Falls, appearing in a handful of games. The next year, he made 33 starts, winning 15 games, pitching 228 innings and leading the Three-I league with 215 strikeouts.

Locker missed the next two seasons due to military service. He returned to baseball in 1964, and winning 16 games for Indianapolis. It would be his last year in the minors.

Chicago White Sox (1965–1969)

[edit]At age 27, Bob Locker had made the big leagues, joining a bullpen that featured knuckleballers Hoyt Wilhelm and Eddie Fisher. He made his debut in Baltimore on April 14, 1965, tossing two innings and giving up three runs. Locker settled down, however, and in a stretch from May 30 to June 20—10 total appearances—he was unscored upon. He would finish his rookie campaign with 93+1⁄3 innings pitched and a 3.15 earned-run average.

During his time in Chicago, Locker was the most often-used reliever. He appeared in 77 games in 1967 and 70 games in 1968. In 1969, Locker got off to a rough start (2–3 record, 6.55 ERA), and on June 8, the White Sox shipped him to the expansion Seattle Pilots for Gary Bell.[2]

Seattle Pilots (1969) / Milwaukee Brewers (1970)

[edit]Upon arriving in Seattle, the 31-year-old Locker began a reversal of fortune, posting a 2.18 ERA for an expansion team that would finish in last place in the division. He finished the season with a flourish, allowing just eight runs in his last 30 appearances on the season.

When the Seattle Pilots moved to Milwaukee at the end of spring training, 1970, Locker went with them and appeared in 28 games for the Brewers.

Oakland Athletics (1970–1972)

[edit]Locker's contract was purchased by the Athletics from the Brewers on June 15, 1970.[3] He made his presence felt once he arrived in Oakland, having allowed no runs in his first seven innings for the Athletics. His most impressive outing came on August 12, 1970, against the Cleveland Indians, in which he pitched 5+2⁄3 of scoreless relief, the longest outing of his career.

In 1972, Locker was a key member of the World Series champion team, posting a 6–1 record and 2.65 ERA, often appearing in the seventh and eighth innings as the setup man for closer Rollie Fingers. Locker struggled in the American League Championship Series against the Detroit Tigers, giving up three runs in two innings of work. On October 21, he made his first and only World Series appearance, relieving Vida Blue with two outs in the sixth inning of Game 6. He gave up a single to Tony Pérez but got the final out of the inning before being removed for a pinch-hitter.

A month later, Oakland traded Locker to the Chicago Cubs for outfielder Billy North.

Chicago Cubs (1973, 1975)

[edit]Pitching in the National League for the first time, Locker had one of his best seasons, winning 10 games, saving 18 and topping 100 innings pitched for the first time since 1969. In an odd twist, he was sent back to the Athletics by the Cubs for Horacio Piña at the Winter Meetings on December 3, 1973.[4] According to Bruce Markusen in his 1998 book, Baseball's Last Dynasty: Charlie Finley's Oakland A's, Locker had told Cubs general manager John Holland that he would only pitch one season for the Cubs, then he wanted to be traded back to the A's as owner Charlie Finley had agreed to try to arrange. Locker moved his family to Oakland and planned to live and work there after his baseball career. Holland and Charlie Finley obliged the pitcher's request but it turned out to be a bad deal for the A's. Locker had to undergo surgery to remove bone chips from his pitching elbow and would sit out the entire 1974 season.

Finley sent Locker back to the Cubs just days after winning the 1974 World Series in exchange for veteran outfielder Billy Williams.[5] Locker's 1975 season would be his last in the majors.

Retirement

[edit]Since April 2010, Locker has been the creator and webmaster of a Marvin Miller tribute site, ThanksMarvin.com.[6] The site collects memorabilia about the late Major League Baseball Player Association Executive Director in an attempt to raise awareness of Miller's importance in the American Labor Unions in the United States and to get Miller elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame when his name came up for a ballot in 2014 as part of the "Expansion Era" group. Miller died on November 27, 2012, at the age of 95, but was selected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in December 2019, for induction in 2020.

Locker died in Bozeman, Montana, on August 15, 2022. He was 84.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Scherer, Keith. "Bob Locker". sabr.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved September 4, 2022.

- ^ "The Milwaukee Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ Durso, Joseph. "Drabowsky Back in Oriole Fold," The New York Times, Wednesday, June 17, 1970. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Durso, Joseph. "4 Trades Made at Meetings," The New York Times, Tuesday, December 4, 1973. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

- ^ "The Day - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ Locker, Bob (2010). "Thanks Marvin". Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ^ Robert Awtry Locker

- Oakland Athletics 1971 Press/Radio/TV Guide. Published by the Oakland A's Baseball Club.

- Markusen, Bruce. Baseball's Last Dynasty: Charlie Finley's Oakland A's. Master Press, Indianapolis, 1998.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB · Baseball Reference · Fangraphs · Baseball Reference (Minors) · Retrosheet · Baseball Almanac