Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bubble point

View on Wikipedia

In thermodynamics, the bubble point is the temperature (at a given pressure) where the first bubble of vapor is formed when heating a liquid consisting of two or more components.[1][2] Given that vapor will probably have a different composition than the liquid, the bubble point (along with the dew point) at different compositions are useful data when designing distillation systems.[3]

For a single component the bubble point and the dew point are the same and are referred to as the boiling point.

Calculating the bubble point

[edit]At the bubble point, the following relationship holds:

where

- .

K is the distribution coefficient or K factor, defined as the ratio of mole fraction in the vapor phase to the mole fraction in the liquid phase at equilibrium.

When Raoult's law and Dalton's law hold for the mixture, the K factor is defined as the ratio of the vapor pressure to the total pressure of the system:[1]

Given either of or and either the temperature or pressure of a two-component system, calculations can be performed to determine the unknown information.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b McCabe, Warren L.; Smith, Julian C.; Harriot, Peter (2005), Unit Operations of Chemical Engineering (seventh ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 737–738, ISBN 0-07-284823-5

- ^ Smith, J. M.; Van Ness, H. C.; Abbott, M. M. (2005), Introduction to Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics (seventh ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 342, ISBN 0-07-310445-0

- ^ Perry, R.H.; Green, D.W., eds. (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-hill. ISBN 0-07-049841-5.

- ^ Smith, J. M.; Van Ness, H. C.; Abbott, M. M. (2005), Introduction to Chemical Engineering Thermodynamics (seventh ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 351, ISBN 0-07-310445-0

Bubble point

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Concepts

Bubble Point Temperature

The bubble point temperature of a liquid mixture is defined as the temperature at which the first bubble of vapor forms upon heating the mixture at constant pressure, marking the initiation of the boiling process for the multicomponent system.[4] This condition represents the point where the liquid phase is in equilibrium with an infinitesimal amount of vapor, with the overall composition matching that of the liquid.[4] At the bubble point temperature, the total vapor pressure exerted by the components in the mixture equals the prevailing system pressure, allowing the formation of the initial vapor bubble while the bulk remains liquid.[4] This equilibrium arises from the summation of partial pressures according to principles such as Raoult's law for ideal solutions, where the vapor composition differs from the liquid due to preferential evaporation of more volatile components.[4] For instance, in a binary mixture like ethanol-water at 1 atm, the bubble point temperature occurs around 78.2°C for pure ethanol but shifts higher with increasing water content, reflecting the interplay of component volatilities.[5] In the case of a pure substance, the bubble point temperature is the boiling point at the given pressure, as there is no compositional variation to influence phase transition. For mixtures, however, this temperature is generally lower than the boiling point of the least volatile component, as the presence of more volatile species accelerates the onset of vaporization.[4] Several factors govern the bubble point temperature: the mixture's composition, where increasing the mole fraction of volatile components decreases the temperature; the system pressure, which exhibits a direct relationship such that higher pressures elevate the required temperature to achieve equilibrium; and the relative volatilities of the components, which widen the temperature range over which boiling progresses in non-ideal mixtures.[4] These elements are fundamentally tied to vapor-liquid equilibrium conditions.[4]Bubble Point Pressure

The bubble point pressure is defined as the pressure at which the first bubble of vapor forms from a liquid mixture upon reduction of the system pressure at constant temperature, marking the onset of vapor-liquid equilibrium for the mixture.[6] This pressure serves as the saturation pressure, below which the liquid becomes unstable and phase separation begins, transitioning the system from a single liquid phase to a two-phase mixture.[7] At the bubble point pressure, the physical process involves the equality between the total system pressure and the sum of the partial pressures exerted by each component in the liquid phase, based on their mole fractions and individual vapor pressures at the given temperature.[8] For ideal mixtures, this follows from Raoult's law, where each partial pressure is the product of the liquid mole fraction and the pure component's saturation vapor pressure, leading to the initiation of infinitesimal vapor formation without significant composition change in the bulk liquid. This equilibrium condition ties into broader phase behavior principles, where the bubble point delineates the boundary of liquid stability under isothermal compression or decompression. In practical contexts, such as underground oil reservoirs, the bubble point pressure indicates the threshold below which dissolved gas evolves from the crude oil, potentially reducing oil mobility and affecting production rates; typical values for conventional reservoir oils range from 1800 to 2600 psi.[7] For pure substances, the bubble point pressure coincides exactly with the vapor pressure at that temperature, as there are no compositional effects to consider.[1] Several factors influence the bubble point pressure, including temperature, which generally increases the pressure due to higher volatility of components; mixture composition, where higher concentrations of lighter, more volatile species elevate the pressure; and intermolecular interactions, which alter activity coefficients and thus deviate from ideal behavior, impacting overall volatility.[7] These influences are captured in empirical correlations like that of Standing (1947), which relates bubble point pressure to solution gas-oil ratio, gas specific gravity, reservoir temperature, and oil API gravity.[9]Thermodynamic Principles

Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium

Vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) represents the state in a system where the liquid and vapor phases coexist with unchanging compositions over time, achieved when the rate of evaporation from the liquid phase equals the rate of condensation from the vapor phase. This dynamic balance ensures that the partial pressures of components in the vapor phase remain constant, reflecting equal molecular exchange between phases./11%3A_Liquids_Solids_and_Intermolecular_Forces/11.05%3A_Vaporization_and_Vapor_Pressure) The Gibbs phase rule governs the constraints on such equilibria, stating that the degrees of freedom in a system is given by , where is the number of components and is the number of phases. For a binary system () at VLE (), , allowing specification of two intensive variables, such as temperature and liquid composition, to uniquely determine the remaining properties like pressure and vapor composition. At the bubble point condition within this framework—where the first infinitesimal vapor bubble forms in equilibrium with the bulk liquid—fixing the pressure and liquid composition (one variable for a binary mixture) determines the equilibrium temperature, effectively reducing the independent variables to align with the univariant nature of the saturation curve for that composition. At VLE, the fundamental criterion for equilibrium is the equality of chemical potentials for each component across phases, which translates to the equality of fugacities: for component , where is the fugacity in the liquid phase and in the vapor phase. Fugacity, analogous to pressure for ideal gases but accounting for non-ideal behavior, ensures that the escaping tendency of each component is identical in both phases, maintaining compositional stability. This condition underpins the thermodynamic consistency of VLE and directly defines the bubble point as the pressure or temperature where this equality holds for the incipient vapor phase matching the overall system pressure./06%3A_Fugacity)[10] While many VLE analyses assume ideal gas behavior for the vapor phase to simplify calculations—treating fugacity as partial pressure—these assumptions falter at high pressures, low temperatures, or near critical points, where intermolecular forces and finite molecular volumes cause significant deviations. In such cases, real gas corrections via equations of state are essential to accurately compute fugacities and predict equilibrium states.[11] Historically, the concept of VLE for ideal mixtures was formalized by Raoult's law, proposed by François-Marie Raoult in 1887, which posits that the partial vapor pressure of each component in an ideal solution is proportional to its mole fraction in the liquid phase. This early model laid the groundwork for understanding ideal VLE behavior and remains a cornerstone for introductory analyses, though extensions for non-ideal systems followed later.[12][13]Role in Phase Behavior

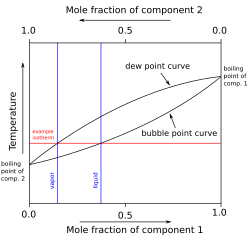

In temperature-composition (T-x-y) phase diagrams at constant pressure, the bubble point curve represents the locus of temperatures at which the first infinitesimal bubble of vapor forms from a liquid mixture of varying compositions, marking the boundary between the single-phase liquid region and the two-phase liquid-vapor region.[14] This curve, often nonlinear for nonideal mixtures, illustrates how the boiling temperature decreases or increases with composition depending on the relative volatilities of the components, providing a visual tool for understanding the onset of vaporization in isothermal or isobaric processes.[15] For binary systems, the bubble point curve forms the lower boundary of the two-phase envelope in T-x-y diagrams, separating the subcooled liquid region from the coexistence area where partial vaporization occurs, and it connects the boiling points of the pure components.[15] In contrast, multicomponent systems are typically represented in pressure-temperature (P-T) space, where the bubble point appears as a line tracing the conditions under which the first vapor bubble emerges from the liquid phase, influenced by the overall composition and forming part of the phase envelope that encloses the two-phase region.[16] Unlike binary systems, which show distinct dew and bubble curves meeting at the critical point, multicomponent behavior extends this to broader envelopes with cricondentherm and cricondenbar points, but the bubble line still delineates the liquid region's limit.[3] The presence of azeotropes significantly alters the shape of the bubble point curve due to strong nonideal interactions between components. In systems forming minimum boiling azeotropes, such as ethanol-water, the curve exhibits a minimum temperature point where the liquid and vapor compositions coincide, causing the bubble and dew curves to touch and deviate from ideal linearity, which complicates separation processes.[4] For maximum boiling azeotropes, like nitric acid-water, the curve instead shows a maximum temperature extremum, resulting in a peaked shape that reverses the typical volatility trend and leads to the azeotrope having a higher boiling point than either pure component.[4] At the bubble point, the phase transition initiates vaporization, where heating a liquid mixture beyond this temperature produces an initial vapor phase enriched in the more volatile components, while the remaining liquid becomes depleted in those components, driving compositional changes across the two-phase region.[17] This selective vaporization underpins distillation and other separation techniques, as the vapor's composition shifts progressively toward the lighter end-member with continued heating until the dew point is reached.[17] Experimental determination of bubble points relies on techniques like ebulliometry, which measures the equilibrium temperature at which vapor bubbles first appear in a boiling liquid under controlled pressure. In a typical setup, an inclined ebulliometer with a stirrer maintains quasi-static conditions, allowing precise temperature readings for binary or multicomponent mixtures as vaporization begins, often validated against models like Raoult's law for ideal cases.[18] This method ensures accurate data for phase diagrams by minimizing superheating and providing reproducible results across composition ranges.[18]Calculation Methods

For Ideal Mixtures

For ideal mixtures, the bubble point is determined under the assumption that the components obey Raoult's law, which states that the partial pressure of each component in the vapor phase is equal to the product of its liquid mole fraction and the saturation vapor pressure of the pure component , or .[19] This ideal behavior assumes no interactions between unlike molecules beyond simple averaging, leading to linear vapor pressure-composition relationships.[19] The fundamental equation for the bubble point condition is the equality of the total pressure to the sum of partial pressures: This equation is solved iteratively for the temperature when and the are specified, as depends on temperature. The saturation vapor pressures are typically calculated using the Antoine equation: where is in bar, is in K, and , , are empirical constants specific to each component, valid over defined temperature ranges (e.g., for benzene from 287.7 to 354.1 K with , , ; for toluene from 308.5 to 384.7 K with , , ).[20][21] The iterative procedure to find the bubble point temperature proceeds as follows:- Select an initial guess for , often between the boiling points of the pure components.

- Compute for each component using the Antoine equation.

- Calculate the sum and compare it to .

- Adjust (increase if the sum is less than , decrease otherwise) and repeat until convergence within a specified tolerance, such as 0.1 K.[22]