Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Phase transition

View on Wikipedia

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic states of matter: solid, liquid, and gas, and in rare cases, plasma. A phase of a thermodynamic system and the states of matter have uniform physical properties. During a phase transition of a given medium, certain properties of the medium change as a result of the change of external conditions, such as temperature or pressure. This can be a discontinuous change; for example, a liquid may become gas upon heating to its boiling point, resulting in an abrupt change in volume. The identification of the external conditions at which a transformation occurs defines the phase transition point.

Types

[edit]States of matter

[edit]

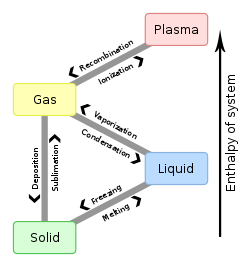

Phase transitions commonly refer to when a substance transforms between one of the four states of matter to another. At the phase transition point for a substance, for instance the boiling point, the two phases involved - liquid and vapor, have identical free energies and therefore are equally likely to exist. Below the boiling point, the liquid is the more stable state of the two, whereas above the boiling point the gaseous form is the more stable.

Common transitions between the solid, liquid, and gaseous phases of a single component, due to the effects of temperature and/or pressure are identified in the following table:

To From

|

Solid | Liquid | Gas | Plasma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Melting | Sublimation | ||

| Liquid | Freezing | Vaporization | ||

| Gas | Deposition | Condensation | Ionization | |

| Plasma | Recombination |

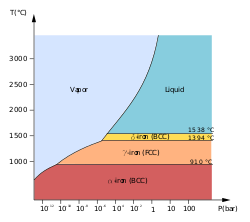

For a single component, the most stable phase at different temperatures and pressures can be shown on a phase diagram. Such a diagram usually depicts states in equilibrium. A phase transition usually occurs when the pressure or temperature changes and the system crosses from one region to another, like water turning from liquid to solid as soon as the temperature drops below the freezing point. In exception to the usual case, it is sometimes possible to change the state of a system diabatically (as opposed to adiabatically) in such a way that it can be brought past a phase transition point without undergoing a phase transition. The resulting state is metastable, i.e., less stable than the phase to which the transition would have occurred, but not unstable either. This occurs in superheating and supercooling, for example. Metastable states do not appear on usual phase diagrams.

Structural

[edit]

Phase transitions can also occur when a solid changes to a different structure without changing its chemical makeup. In elements, this is known as allotropy, whereas in compounds it is known as polymorphism. The change from one crystal structure to another, from a crystalline solid to an amorphous solid, or from one amorphous structure to another (polyamorphs) are all examples of solid to solid phase transitions.

The martensitic transformation occurs as one of the many phase transformations in carbon steel and stands as a model for displacive phase transformations. Order-disorder transitions such as in alpha-titanium aluminides. As with states of matter, there is also a metastable to equilibrium phase transformation for structural phase transitions. A metastable polymorph which forms rapidly due to lower surface energy will transform to an equilibrium phase given sufficient thermal input to overcome an energetic barrier.

Many dynamic, or soft, Microporous materials exhibit structural phase transitions between closed and open forms. Metal–organic frameworks, in particular, have been extensively studied for this behavior. The phase landscape can be more complex, with intermediate phases discovered.[1] Further examples show that guest molecules can stabilize specific phases, resulting in crystal configurations that depend on the composition of the surrounding atmosphere.[2]

Magnetic

[edit]

Phase transitions can also describe the change between different kinds of magnetic ordering. The most well-known is the transition between the ferromagnetic and paramagnetic phases of magnetic materials, which occurs at what is called the Curie point. Another example is the transition between differently ordered, commensurate or incommensurate, magnetic structures, such as in cerium antimonide. A simplified but highly useful model of magnetic phase transitions is provided by the Ising model.

Mixtures

[edit]

Phase transitions involving solutions and mixtures are more complicated than transitions involving a single compound. While chemically pure compounds exhibit a single temperature melting point between solid and liquid phases, mixtures can either have a single melting point, known as congruent melting, or they have different liquidus and solidus temperatures resulting in a temperature span where solid and liquid coexist in equilibrium. This is often the case in solid solutions, where the two components are isostructural.

There are also a number of phase transitions involving three phases: a eutectic transformation, in which a two-component single-phase liquid is cooled and transforms into two solid phases. The same process, but beginning with a solid instead of a liquid is called a eutectoid transformation. A peritectic transformation, in which a two-component single-phase solid is heated and transforms into a solid phase and a liquid phase. A peritectoid reaction is a peritectoid reaction, except involving only solid phases. A monotectic reaction consists of change from a liquid and to a combination of a solid and a second liquid, where the two liquids display a miscibility gap.[3]

Separation into multiple phases can occur via spinodal decomposition, in which a single phase is cooled and separates into two different compositions.

Non-equilibrium mixtures can occur, such as in supersaturation.

Other examples

[edit]

Other phase changes include:

- Microphase separation in block copolymers.[4][5]

- Transition to a mesophase between solid and liquid, such as one of the "liquid crystal" phases.

- The dependence of the adsorption geometry on coverage and temperature, such as for hydrogen on iron (110).

- The emergence of superconductivity in certain metals and ceramics when cooled below a critical temperature.

- The emergence of metamaterial properties in artificial photonic media as their parameters are varied.[6][7]

- Quantum condensation of bosonic fluids (Bose–Einstein condensation). The superfluid transition in liquid helium is an example of this.

- The breaking of symmetries in the laws of physics during the early history of the universe as its temperature cooled.

- Isotope fractionation occurs during a phase transition, the ratio of light to heavy isotopes in the involved molecules changes. When water vapor condenses (an equilibrium fractionation), the heavier water isotopes (18O and 2H) become enriched in the liquid phase while the lighter isotopes (16O and 1H) tend toward the vapor phase.[8]

Phase transitions occur when the thermodynamic free energy of a system is non-analytic for some choice of thermodynamic variables (cf. phases). This condition generally stems from the interactions of a large number of particles in a system, and does not appear in systems that are small. Phase transitions can occur for non-thermodynamic systems, where temperature is not a parameter. Examples include: quantum phase transitions, dynamic phase transitions, and topological (structural) phase transitions. In these types of systems other parameters take the place of temperature. For instance, connection probability replaces temperature for percolating networks.

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

Classifications

[edit]Ehrenfest classification

[edit]Paul Ehrenfest classified phase transitions based on the behavior of the thermodynamic free energy as a function of other thermodynamic variables.[9] Under this scheme, phase transitions were labeled by the lowest derivative of the free energy that is discontinuous at the transition. First-order phase transitions exhibit a discontinuity in the first derivative of the free energy with respect to some thermodynamic variable.[10] The various solid/liquid/gas transitions are classified as first-order transitions because they involve a discontinuous change in density, which is the (inverse of the) first derivative of the free energy with respect to pressure. Second-order phase transitions are continuous in the first derivative (the order parameter, which is the first derivative of the free energy with respect to the external field, is continuous across the transition) but exhibit discontinuity in a second derivative of the free energy.[10] These include the ferromagnetic phase transition in materials such as iron, where the magnetization, which is the first derivative of the free energy with respect to the applied magnetic field strength, increases continuously from zero as the temperature is lowered below the Curie temperature. The magnetic susceptibility, the second derivative of the free energy with the field, changes discontinuously. Under the Ehrenfest classification scheme, there could in principle be third, fourth, and higher-order phase transitions. For example, the Gross–Witten–Wadia phase transition in 2-d lattice quantum chromodynamics is a third-order phase transition, and the Tracy–Widom distribution can be interpreted as a third-order transition.[11][12] The Curie points of many ferromagnetics is also a third-order transition, as shown by their specific heat having a sudden change in slope.[13][14]

In practice, only the first- and second-order phase transitions are typically observed. The second-order phase transition was for a while controversial, as it seems to require two sheets of the Gibbs free energy to osculate exactly, which is so unlikely as to never occur in practice. Cornelis Gorter replied the criticism by pointing out that the Gibbs free energy surface might have two sheets on one side, but only one sheet on the other side, creating a forked appearance.[15] ([13] pp. 146--150)

The Ehrenfest classification implicitly allows for continuous phase transformations, where the bonding character of a material changes, but there is no discontinuity in any free energy derivative. An example of this occurs at the supercritical liquid–gas boundaries.

The first example of a phase transition which did not fit into the Ehrenfest classification was the exact solution of the Ising model, discovered in 1944 by Lars Onsager. The exact specific heat differed from the earlier mean-field approximations, which had predicted that it has a simple discontinuity at critical temperature. Instead, the exact specific heat had a logarithmic divergence at the critical temperature.[16] In the following decades, the Ehrenfest classification was replaced by a simplified classification scheme that is able to incorporate such transitions.

Modern classifications

[edit]In the modern classification scheme, phase transitions are divided into two broad categories, named similarly to the Ehrenfest classes:[9]

First-order phase transitions are those that involve a latent heat. During such a transition, a system either absorbs or releases a fixed (and typically large) amount of energy per volume. During this process, the temperature of the system will stay constant as heat is added: the system is in a "mixed-phase regime" in which some parts of the system have completed the transition and others have not.[17][18]

Familiar examples are the melting of ice or the boiling of water (the water does not instantly turn into vapor, but forms a turbulent mixture of liquid water and vapor bubbles). Yoseph Imry and Michael Wortis showed that quenched disorder can broaden a first-order transition. That is, the transformation is completed over a finite range of temperatures, but phenomena like supercooling and superheating survive and hysteresis is observed on thermal cycling.[19][20][21]

Second-order phase transitions are also called "continuous phase transitions". They are characterized by a divergent susceptibility, an infinite correlation length, and a power law decay of correlations near criticality. Examples of second-order phase transitions are the ferromagnetic transition, superconducting transition (for a Type-I superconductor the phase transition is second-order at zero external field and for a Type-II superconductor the phase transition is second-order for both normal-state–mixed-state and mixed-state–superconducting-state transitions) and the superfluid transition. In contrast to viscosity, thermal expansion and heat capacity of amorphous materials show a relatively sudden change at the glass transition temperature[22] which enables accurate detection using differential scanning calorimetry measurements. Lev Landau gave a phenomenological theory of second-order phase transitions.

Apart from isolated, simple phase transitions, there exist transition lines as well as multicritical points, when varying external parameters like the magnetic field or composition.

Several transitions are known as infinite-order phase transitions. They are continuous but break no symmetries. The most famous example is the Kosterlitz–Thouless transition in the two-dimensional XY model. Many quantum phase transitions, e.g., in two-dimensional electron gases, belong to this class.

The liquid–glass transition is observed in many polymers and other liquids that can be supercooled far below the melting point of the crystalline phase. This is atypical in several respects. It is not a transition between thermodynamic ground states: it is widely believed that the true ground state is always crystalline. Glass is a quenched disorder state, and its entropy, density, and so on, depend on the thermal history. Therefore, the glass transition is primarily a dynamic phenomenon: on cooling a liquid, internal degrees of freedom successively fall out of equilibrium. Some theoretical methods predict an underlying phase transition in the hypothetical limit of infinitely long relaxation times.[23][24] No direct experimental evidence supports the existence of these transitions.

Characteristic properties

[edit]Phase coexistence

[edit]A disorder-broadened first-order transition occurs over a finite range of temperatures where the fraction of the low-temperature equilibrium phase grows from zero to one (100%) as the temperature is lowered. This continuous variation of the coexisting fractions with temperature raised interesting possibilities. On cooling, some liquids vitrify into a glass rather than transform to the equilibrium crystal phase. This happens if the cooling rate is faster than a critical cooling rate, and is attributed to the molecular motions becoming so slow that the molecules cannot rearrange into the crystal positions.[25] This slowing down happens below a glass-formation temperature Tg, which may depend on the applied pressure.[22][26] If the first-order freezing transition occurs over a range of temperatures, and Tg falls within this range, then there is an interesting possibility that the transition is arrested when it is partial and incomplete. Extending these ideas to first-order magnetic transitions being arrested at low temperatures, resulted in the observation of incomplete magnetic transitions, with two magnetic phases coexisting, down to the lowest temperature. First reported in the case of a ferromagnetic to anti-ferromagnetic transition,[27] such persistent phase coexistence has now been reported across a variety of first-order magnetic transitions. These include colossal-magnetoresistance manganite materials,[28][29] magnetocaloric materials,[30] magnetic shape memory materials,[31] and other materials.[32] The interesting feature of these observations of Tg falling within the temperature range over which the transition occurs is that the first-order magnetic transition is influenced by magnetic field, just like the structural transition is influenced by pressure. The relative ease with which magnetic fields can be controlled, in contrast to pressure, raises the possibility that one can study the interplay between Tg and Tc in an exhaustive way. Phase coexistence across first-order magnetic transitions will then enable the resolution of outstanding issues in understanding glasses.

Critical points

[edit]In any system containing liquid and gaseous phases, there exists a special combination of pressure and temperature, known as the critical point, at which the transition between liquid and gas becomes a second-order transition. Near the critical point, the fluid is sufficiently hot and compressed that the distinction between the liquid and gaseous phases is almost non-existent. This is associated with the phenomenon of critical opalescence, a milky appearance of the liquid due to density fluctuations at all possible wavelengths (including those of visible light).

Symmetry

[edit]Phase transitions often involve a symmetry breaking process. For instance, the cooling of a fluid into a crystalline solid breaks continuous translation symmetry: each point in the fluid has the same properties, but each point in a crystal does not have the same properties (unless the points are chosen from the lattice points of the crystal lattice). Typically, the high-temperature phase contains more symmetries than the low-temperature phase due to spontaneous symmetry breaking, with the exception of certain accidental symmetries (e.g. the formation of heavy virtual particles, which only occurs at low temperatures).[33]

Order parameters

[edit]An order parameter is a measure of the degree of order across the boundaries in a phase transition system; it normally ranges between zero in one phase (usually above the critical point) and nonzero in the other.[34] At the critical point, the order parameter susceptibility will usually diverge.

An example of an order parameter is the net magnetization in a ferromagnetic system undergoing a phase transition. For liquid/gas transitions, the order parameter is the difference of the densities.

From a theoretical perspective, order parameters arise from symmetry breaking. When this happens, one needs to introduce one or more extra variables to describe the state of the system. For example, in the ferromagnetic phase, one must provide the net magnetization, whose direction was spontaneously chosen when the system cooled below the Curie point. However, note that order parameters can also be defined for non-symmetry-breaking transitions.[citation needed]

Some phase transitions, such as superconducting and ferromagnetic, can have order parameters for more than one degree of freedom. In such phases, the order parameter may take the form of a complex number, a vector, or even a tensor, the magnitude of which goes to zero at the phase transition.[citation needed]

There also exist dual descriptions of phase transitions in terms of disorder parameters. These indicate the presence of line-like excitations such as vortex- or defect lines.

Relevance in cosmology

[edit]Symmetry-breaking phase transitions play an important role in cosmology. As the universe expanded and cooled, the vacuum underwent a series of symmetry-breaking phase transitions. For example, the electroweak transition broke the SU(2)×U(1) symmetry of the electroweak field into the U(1) symmetry of the present-day electromagnetic field. This transition is important to explain the asymmetry between the amount of matter and antimatter in the present-day universe, according to electroweak baryogenesis theory.

Progressive phase transitions in an expanding universe are implicated in the development of order in the universe, as is illustrated by the work of Eric Chaisson[35] and David Layzer.[36]

See also relational order theories and order and disorder.

Critical exponents and universality classes

[edit]Continuous phase transitions are easier to study than first-order transitions due to the absence of latent heat, and they have been discovered to have many interesting properties. The phenomena associated with continuous phase transitions are called critical phenomena, due to their association with critical points.

Continuous phase transitions can be characterized by parameters known as critical exponents. The most important one is perhaps the exponent describing the divergence of the thermal correlation length by approaching the transition. For instance, let us examine the behavior of the heat capacity near such a transition. We vary the temperature T of the system while keeping all the other thermodynamic variables fixed and find that the transition occurs at some critical temperature Tc. When T is near Tc, the heat capacity C typically has a power law behavior:

The heat capacity of amorphous materials has such a behaviour near the glass transition temperature where the universal critical exponent α = 0.59[37] A similar behavior, but with the exponent ν instead of α, applies for the correlation length.

The critical exponents are not necessarily the same above and below the critical temperature. When a continuous symmetry is explicitly broken down to a discrete symmetry by irrelevant (in the renormalization group sense) anisotropies, then some exponents (such as , the exponent of the susceptibility) are not identical.[38]

For , the heat capacity remains differentiable at the transition temperature, although discontinuities appear at higher-order derivatives.[39]

For , the heat capacity has a "kink" at the transition temperature. This is the behavior of liquid helium at the lambda transition from a normal state to the superfluid state, for which experiments have found α = −0.013 ± 0.003. At least one experiment was performed in the zero-gravity conditions of an orbiting satellite to minimize pressure differences in the sample.[40] This experimental value of α agrees with theoretical predictions based on variational perturbation theory.[41]

For 0 < α < 1, the heat capacity diverges at the transition temperature (though, since α < 1, the enthalpy stays finite). An example of such behavior is the 3D ferromagnetic phase transition. In the three-dimensional Ising model for uniaxial magnets, detailed theoretical studies have yielded the exponent α ≈ +0.110.

Some model systems do not obey a power-law behavior. For example, mean field theory predicts a finite discontinuity of the heat capacity at the transition temperature, and the two-dimensional Ising model has a logarithmic divergence. However, these systems are limiting cases and an exception to the rule. Real phase transitions exhibit power-law behavior.

Several other critical exponents, β, γ, δ, ν, and η, are defined, examining the power law behavior of a measurable physical quantity near the phase transition. Exponents are related by scaling relations, such as

It can be shown that there are only two independent exponents, e.g. ν and η.

It is a remarkable fact that phase transitions arising in different systems often possess the same set of critical exponents. This phenomenon is known as universality. For example, the critical exponents at the liquid–gas critical point have been found to be independent of the chemical composition of the fluid.

More impressively, but understandably from above, they are an exact match for the critical exponents of the ferromagnetic phase transition in uniaxial magnets. Such systems are said to be in the same universality class. Universality is a prediction of the renormalization group theory of phase transitions, which states that the thermodynamic properties of a system near a phase transition depend only on a small number of features, such as dimensionality and symmetry, and are insensitive to the underlying microscopic properties of the system. Again, the divergence of the correlation length is the essential point.

Critical phenomena

[edit]There are also other critical phenomena; e.g., besides static functions there is also critical dynamics. As a consequence, at a phase transition one may observe critical slowing down or speeding up. Connected to the previous phenomenon is also the phenomenon of enhanced fluctuations before the phase transition, as a consequence of lower degree of stability of the initial phase of the system. The large static universality classes of a continuous phase transition split into smaller dynamic universality classes. In addition to the critical exponents, there are also universal relations for certain static or dynamic functions of the magnetic fields and temperature differences from the critical value.[citation needed]

Experimental

[edit]A variety of methods are applied for studying the various effects. Selected examples are:

- Hall effect (measurement of magnetic transitions)

- Mössbauer spectroscopy (simultaneous measurement of magnetic and non-magnetic transitions. Limited up to about 800–1000 °C)

- Neutron diffraction

- Perturbed angular correlation (simultaneous measurement of magnetic and non-magnetic transitions. No temperature limits. Over 2000 °C already performed, theoretical possible up to the highest crystal material, such as tantalum hafnium carbide 4215 °C.)

- Raman Spectroscopy

- SQUID (measurement of magnetic transitions)

- Thermogravimetry (very common)

- X-ray diffraction

In other systems

[edit]Phase transitions in biology

[edit]Phase transitions play many important roles in biological systems. Examples include the lipid bilayer formation, the coil-globule transition in the process of protein folding and DNA melting, liquid crystal-like transitions in the process of DNA condensation, cooperative ligand binding to DNA and proteins with the character of phase transition[42] or the change in the process of genetic expression at the onset of eukaryotes, marked by an algorithmic phase transition.[43]

In biological membranes, gel to liquid crystalline phase transitions play a critical role in physiological functioning of biomembranes. In gel phase, due to low fluidity of membrane lipid fatty-acyl chains, membrane proteins have restricted movement and thus are restrained in exercise of their physiological role. Plants depend critically on photosynthesis by chloroplast thylakoid membranes which are exposed cold environmental temperatures. Thylakoid membranes retain innate fluidity even at relatively low temperatures because of high degree of fatty-acyl disorder allowed by their high content of linolenic acid, 18-carbon chain with 3-double bonds.[44] Gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition temperature of biological membranes can be determined by many techniques including calorimetry, fluorescence, spin label electron paramagnetic resonance and NMR by recording measurements of the concerned parameter by at series of sample temperatures. A simple method for its determination from 13-C NMR line intensities has also been proposed.[45]

It has been proposed that some biological systems might lie near critical points. Examples include neural networks in the salamander retina,[46] bird flocks[47] gene expression networks in Drosophila,[48] and protein folding.[49] However, it is not clear whether or not alternative reasons could explain some of the phenomena supporting arguments for criticality.[50] It has also been suggested that biological organisms share two key properties of phase transitions: the change of macroscopic behavior and the coherence of a system at a critical point.[51] Phase transitions are prominent feature of motor behavior in biological systems.[52] Spontaneous gait transitions,[53] as well as fatigue-induced motor task disengagements,[54] show typical critical behavior as an intimation of the sudden qualitative change of the previously stable motor behavioral pattern.

The characteristic feature of second order phase transitions is the appearance of fractals in some scale-free properties. It has long been known that protein globules are shaped by interactions with water. There are 20 amino acids that form side groups on protein peptide chains range from hydrophilic to hydrophobic, causing the former to lie near the globular surface, while the latter lie closer to the globular center. Twenty fractals were discovered in solvent associated surface areas of > 5000 protein segments.[55] The existence of these fractals proves that proteins function near critical points of second-order phase transitions.

In groups of organisms in stress (when approaching critical transitions), correlations tend to increase, while at the same time, fluctuations also increase. This effect is supported by many experiments and observations of groups of people, mice, trees, and grassy plants.[56]

Phase transitions in social systems

[edit]Phase transitions have been hypothesised to occur in social systems viewed as dynamical systems. A hypothesis proposed in the 1990s and 2000s in the context of peace and armed conflict is that when a conflict that is non-violent shifts to a phase of armed conflict, this is a phase transition from latent to manifest phases within the dynamical system.[57]: 49

See also

[edit]- Allotropy – Property of some chemical elements to exist in two or more different forms

- Autocatalytic reactions and order creation – Chemical reaction whose product is also its catalyst

- Crystal growth – Major stage of a crystallization process

- Abnormal grain growth – Phenomenon of certain material grains growing faster than others

- Differential scanning calorimetry – Thermoanalytical technique

- Diffusionless transformations – Shift of atomic positions in a crystal structure

- Ehrenfest equations

- Ising Model – Mathematical model of ferromagnetism in statistical mechanics

- Jamming (physics)

- Kelvin probe force microscope – Noncontact variant of atomic force microscopy

- Landau theory – Theory of continuous phase transitions of second order phase transitions

- Laser-heated pedestal growth – Crystal growth technique

- List of states of matter – States of Matter

- Micro-pulling-down – Crystal growth technique

- Percolation theory – Mathematical theory on behavior of connected clusters in a random graph

- Continuum percolation theory – Branch of mathematics in probability theory

- Superfluid film – Thin layer of liquid in a superfluid state

- Superradiant phase transition – Process in quantum optics

- Topological quantum field theory – Field theory involving topological effects in physics

References

[edit]- ^ Liu, Yun; Her, Jae-Hyuk; Dailly, Anne; Ramirez-Cuesta, Anibal J.; Neumann, Dan A.; Brown, Craig M. (2008). "Reversible structural transition in MIL-53 with large temperature hysteresis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (35): 11813–11818. doi:10.1021/ja803669w. PMID 18693731.

- ^ Stracke, K; Evans, JD (2025). "Investigating the Temperature-Induced Expansion of MIL-53 under Different Gas Environments Using Molecular Simulations". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 129 (6): 3226–3233. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.4c10584 (inactive 6 September 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of September 2025 (link) - ^ Askeland, Donald R.; Haddleton, Frank; Green, Phil; Robertson, Howard (1996). The Science and Engineering of Materials. Chapman & Hall. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-412-53910-7.

- ^ "Block Copolymer Theory. III. Statistical Mechanics of the Microdomain Structure," Eugene Helfand, Macromolecules 1975, 8, 4, 552-556, https://doi.org/10.1021/ma60046a032

- ^ "Microphase segregation in molten randomly grafted copolymers," Shuyan Qi et. al., Journal of Chemical Physics 115, 3387-3400 (2001), https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1382856

- ^ Rybin, M.V.; et al. (2015). "Phase diagram for the transition from photonic crystals to dielectric metamaterials". Nature Communications. 6 10102. arXiv:1507.08901. Bibcode:2015NatCo...610102R. doi:10.1038/ncomms10102. PMC 4686770. PMID 26626302.

- ^ Eds. Zhou, W., and Fan. S., Semiconductors and Semimetals. Vol 100. Photonic Crystal Metasurface Optoelectronics Archived 25 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Elsevier, 2019

- ^ Carol Kendall (2004). "Fundamentals of Stable Isotope Geochemistry". USGS. Archived from the original on 16 October 2000. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ a b Jaeger, Gregg (1 May 1998). "The Ehrenfest Classification of Phase Transitions: Introduction and Evolution". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 53 (1): 51–81. doi:10.1007/s004070050021. S2CID 121525126.

- ^ a b Blundell, Stephen J.; Katherine M. Blundell (2008). Concepts in Thermal Physics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856770-7.

- ^ Gross, David J. (1980), "Possible third-order phase transition in the large N lattice gauge theory", Physical Review D, 21 (2): 446–453, Bibcode:1980PhRvD..21..446G, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.21.446

- ^ Majumdar, Satya N; Schehr, Grégory (31 January 2014). "Top eigenvalue of a random matrix: large deviations and third order phase transition". Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment. 2014 (1) P01012. arXiv:1311.0580. Bibcode:2014JSMTE..01..012M. doi:10.1088/1742-5468/2014/01/P01012. ISSN 1742-5468. S2CID 119122520.

- ^ a b Pippard, Alfred B. (1981). Elements of classical thermodynamics: for advanced students of physics (Repr ed.). Cambridge: Univ. Pr. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-521-09101-5.

- ^ Austin, J. B. (November 1932). "Heat Capacity of Iron - A Review". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 24 (11): 1225–1235. doi:10.1021/ie50275a006. ISSN 0019-7866.

- ^ Jaeger, Gregg (1 May 1998). "The Ehrenfest Classification of Phase Transitions: Introduction and Evolution". Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 53 (1): 51–81. doi:10.1007/s004070050021. ISSN 1432-0657.

- ^ Stanley, H. Eugene (1971). Introduction to Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Faghri, A., and Zhang, Y., Transport Phenomena in Multiphase Systems, Elsevier, Burlington, MA, 2006,

- ^ Faghri, A., and Zhang, Y., Fundamentals of Multiphase Heat Transfer and Flow Archived 14 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Springer, New York, NY, 2020

- ^ Imry, Y.; Wortis, M. (1979). "Influence of quenched impurities on first-order phase transitions". Phys. Rev. B. 19 (7): 3580–3585. Bibcode:1979PhRvB..19.3580I. doi:10.1103/physrevb.19.3580.

- ^ Kumar, Kranti; Pramanik, A. K.; Banerjee, A.; Chaddah, P.; Roy, S. B.; Park, S.; Zhang, C. L.; Cheong, S.-W. (2006). "Relating supercooling and glass-like arrest of kinetics for phase separated systems: DopedCeFe2and(La,Pr,Ca)MnO3". Physical Review B. 73 (18) 184435. arXiv:cond-mat/0602627. Bibcode:2006PhRvB..73r4435K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.73.184435. ISSN 1098-0121. S2CID 117080049.

- ^ Pasquini, G.; Daroca, D. Pérez; Chiliotte, C.; Lozano, G. S.; Bekeris, V. (2008). "Ordered, Disordered, and Coexistent Stable Vortex Lattices inNbSe2Single Crystals". Physical Review Letters. 100 (24) 247003. arXiv:0803.0307. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100x7003P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.247003. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 18643617. S2CID 1568288.

- ^ a b Ojovan, M.I. (2013). "Ordering and structural changes at the glass-liquid transition". J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 382: 79–86. Bibcode:2013JNCS..382...79O. doi:10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2013.10.016.

- ^ Gotze, Wolfgang. "Complex Dynamics of Glass-Forming Liquids: A Mode-Coupling Theory."

- ^ Lubchenko, V. Wolynes; Wolynes, Peter G. (2007). "Theory of Structural Glasses and Supercooled Liquids". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 58: 235–266. arXiv:cond-mat/0607349. Bibcode:2007ARPC...58..235L. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104653. PMID 17067282. S2CID 46089564.

- ^ Greer, A. L. (1995). "Metallic Glasses". Science. 267 (5206): 1947–1953. Bibcode:1995Sci...267.1947G. doi:10.1126/science.267.5206.1947. PMID 17770105. S2CID 220105648.

- ^ Tarjus, G. (2007). "Materials science: Metal turned to glass". Nature. 448 (7155): 758–759. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..758T. doi:10.1038/448758a. PMID 17700684. S2CID 4410586.

- ^ Manekar, M. A.; Chaudhary, S.; Chattopadhyay, M. K.; Singh, K. J.; Roy, S. B.; Chaddah, P. (2001). "First-order transition from antiferromagnetism to ferromagnetism inCe(Fe0.96Al0.04)2". Physical Review B. 64 (10) 104416. arXiv:cond-mat/0012472. Bibcode:2001PhRvB..64j4416M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.64.104416. ISSN 0163-1829. S2CID 16851501.

- ^ Banerjee, A.; Pramanik, A. K.; Kumar, Kranti; Chaddah, P. (2006). "Coexisting tunable fractions of glassy and equilibrium long-range-order phases in manganites". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 18 (49): L605. arXiv:cond-mat/0611152. Bibcode:2006JPCM...18L.605B. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/49/L02. S2CID 98145553.

- ^ Wu W.; Israel C.; Hur N.; Park S.; Cheong S. W.; de Lozanne A. (2006). "Magnetic imaging of a supercooling glass transition in a weakly disordered ferromagnet". Nature Materials. 5 (11): 881–886. Bibcode:2006NatMa...5..881W. doi:10.1038/nmat1743. PMID 17028576. S2CID 9036412.

- ^ Roy, S. B.; Chattopadhyay, M. K.; Chaddah, P.; Moore, J. D.; Perkins, G. K.; Cohen, L. F.; Gschneidner, K. A.; Pecharsky, V. K. (2006). "Evidence of a magnetic glass state in the magnetocaloric material Gd5Ge4". Physical Review B. 74 (1) 012403. Bibcode:2006PhRvB..74a2403R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.74.012403. ISSN 1098-0121.

- ^ Lakhani, Archana; Banerjee, A.; Chaddah, P.; Chen, X.; Ramanujan, R. V. (2012). "Magnetic glass in shape memory alloy: Ni45Co5Mn38Sn12". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 24 (38) 386004. arXiv:1206.2024. Bibcode:2012JPCM...24L6004L. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/24/38/386004. ISSN 0953-8984. PMID 22927562. S2CID 206037831.

- ^ Kushwaha, Pallavi; Lakhani, Archana; Rawat, R.; Chaddah, P. (2009). "Low-temperature study of field-induced antiferromagnetic-ferromagnetic transition in Pd-doped Fe-Rh". Physical Review B. 80 (17) 174413. arXiv:0911.4552. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..80q4413K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.174413. ISSN 1098-0121. S2CID 119165221.

- ^ Ivancevic, Vladimir G.; Ivancevic, Tijiana, T. (2008). Complex Nonlinearity. Berlin: Springer. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-3-540-79357-1. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Clark, J.B.; Hastie, J.W.; Kihlborg, L.H.E.; Metselaar, R.; Thackeray, M.M. (1994). "Definitions of terms relating to phase transitions of the solid state". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 66 (3): 577–594. doi:10.1351/pac199466030577. S2CID 95616565.

- ^ Chaisson, Eric J. (2001). Cosmic Evolution. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00342-2.

- ^ David Layzer, Cosmogenesis, The Development of Order in the Universe, Oxford Univ. Press, 1991

- ^ Ojovan, Michael I.; Lee, William E. (2006). "Topologically disordered systems at the glass transition" (PDF). Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 18 (50): 11507–11520. Bibcode:2006JPCM...1811507O. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/50/007. S2CID 96326822.

- ^ Leonard, F.; Delamotte, B. (2015). "Critical exponents can be different on the two sides of a transition". Phys. Rev. Lett. 115 (20) 200601. arXiv:1508.07852. Bibcode:2015PhRvL.115t0601L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.200601. PMID 26613426. S2CID 22181730.

- ^ Campbell, I. A.; Petit, D.; Mari, P. O.; Bernardi, L. W. (1999). "Critical exponents in spin glasses: Numerics and experiments". arXiv:cond-mat/9912235.

- ^ Lipa, J.; Nissen, J.; Stricker, D.; Swanson, D.; Chui, T. (2003). "Specific heat of liquid helium in zero gravity very near the lambda point". Physical Review B. 68 (17) 174518. arXiv:cond-mat/0310163. Bibcode:2003PhRvB..68q4518L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.68.174518. S2CID 55646571.

- ^ Kleinert, Hagen (1999). "Critical exponents from seven-loop strong-coupling φ4 theory in three dimensions". Physical Review D. 60 (8) 085001. arXiv:hep-th/9812197. Bibcode:1999PhRvD..60h5001K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.60.085001. S2CID 117436273.

- ^ D.Y. Lando and V.B. Teif (2000). "Long-range interactions between ligands bound to a DNA molecule give rise to adsorption with the character of phase transition of the first kind". J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 17 (5): 903–911. doi:10.1080/07391102.2000.10506578. PMID 10798534. S2CID 23837885.

- ^ Muro, Enrique M.; Ballesteros, Fernando J.; Luque, Bartolo; Bascompte, Jordi (2025). "The emergence of eukaryotes as an evolutionary algorithmic phase transition". PNAS. 122 (13) e2422968122. Bibcode:2025PNAS..12222968M. doi:10.1073/pnas.2422968122. PMC 12002324. PMID 40146859.

- ^ Yashroy RC (1987). "13C NMR studies of lipid fatty acyl chains of chloroplast membranes". Indian Journal of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 24 (6): 177–178. doi:10.1016/0165-022X(91)90019-S. PMID 3428918.

- ^ YashRoy, R C (1990). "Determination of membrane lipid phase transition temperature from 13-C NMR intensities". Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods. 20 (4): 353–356. doi:10.1016/0165-022X(90)90097-V. PMID 2365951.

- ^ Tkacik, Gasper; Mora, Thierry; Marre, Olivier; Amodei, Dario; Berry II, Michael J.; Bialek, William (2014). "Thermodynamics for a network of neurons: Signatures of criticality". arXiv:1407.5946 [q-bio.NC].

- ^ Bialek, W; Cavagna, A; Giardina, I (2014). "Social interactions dominate speed control in poising natural flocks near criticality". PNAS. 111 (20): 7212–7217. arXiv:1307.5563. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.7212B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1324045111. PMC 4034227. PMID 24785504.

- ^ Krotov, D; Dubuis, J O; Gregor, T; Bialek, W (2014). "Morphogenesis at criticality". PNAS. 111 (10): 3683–3688. arXiv:1309.2614. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.3683K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1324186111. PMC 3956198. PMID 24516161.

- ^ Mora, Thierry; Bialek, William (2011). "Are biological systems poised at criticality?". Journal of Statistical Physics. 144 (2): 268–302. arXiv:1012.2242. Bibcode:2011JSP...144..268M. doi:10.1007/s10955-011-0229-4. S2CID 703231.

- ^ Schwab, David J; Nemenman, Ilya; Mehta, Pankaj (2014). "Zipf's law and criticality in multivariate data without fine-tuning". Physical Review Letters. 113 (6) 068102. arXiv:1310.0448. Bibcode:2014PhRvL.113f8102S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.068102. PMC 5142845. PMID 25148352.

- ^ Longo, G.; Montévil, M. (1 August 2011). "From physics to biology by extending criticality and symmetry breakings". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. Systems Biology and Cancer. 106 (2): 340–347. arXiv:1103.1833. doi:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.03.005. PMID 21419157. S2CID 723820.

- ^ Kelso, J. A. Scott (1995). Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior (Complex Adaptive Systems). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-61131-2.

- ^ Diedrich, F. J.; Warren, W. H. Jr. (1995). "Why change gaits? Dynamics of the walk-run transition". Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance. 21 (1): 183–202. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.21.1.183. PMID 7707029.

- ^ Hristovski, R.; Balagué, N. (2010). "Fatigue-induced spontaneous termination point--nonequilibrium phase transitions and critical behavior in quasi-isometric exertion". Human Movement Science. 29 (4): 483–493. doi:10.1016/j.humov.2010.05.004. PMID 20619908.

- ^ Moret, Marcelo; Zebende, Gilney (January 2007). "Amino acid hydrophobicity and accessible surface area". Physical Review E. 75 (1) 011920. Bibcode:2007PhRvE..75a1920M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.75.011920. PMID 17358197.

- ^ Gorban, A.N.; Smirnova, E.V.; Tyukina, T.A. (August 2010). "Correlations, risk and crisis: From physiology to finance". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications. 389 (16): 3193–3217. arXiv:0905.0129. Bibcode:2010PhyA..389.3193G. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2010.03.035. S2CID 276956. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Diane Hendrick (June 2009), Complexity Theory and Conflict Transformation: An Exploration of Potential and Implications (PDF), Department of Peace Studies, University of Bradford, Wikidata Q126669745, archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2022

Further reading

[edit]- Anderson, P.W., Basic Notions of Condensed Matter Physics, Perseus Publishing (1997).

- Faghri, A., and Zhang, Y., Fundamentals of Multiphase Heat Transfer and Flow Archived 14 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020.

- Fisher, M.E. (1974). "The renormalization group in the theory of critical behavior". Rev. Mod. Phys. 46 (4): 597–616. Bibcode:1974RvMP...46..597F. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.46.597.

- Goldenfeld, N., Lectures on Phase Transitions and the Renormalization Group, Perseus Publishing (1992).

- Ivancevic, Vladimir G; Ivancevic, Tijana T (2008), Chaos, Phase Transitions, Topology Change and Path Integrals, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-79356-4, retrieved 14 March 2013

- M.R. Khoshbin-e-Khoshnazar, Ice Phase Transition as a sample of finite system phase transition, (Physics Education (India) Volume 32. No. 2, Apr - Jun 2016) Archived 29 April 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- Kleinert, H., Gauge Fields in Condensed Matter, Vol. I, "Superfluidity and Vortex lines; Disorder Fields, Phase Transitions", pp. 1–742, World Scientific (Singapore, 1989); Paperback ISBN 9971-5-0210-0 (physik.fu-berlin.de readable online Archived 27 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine)

- Kleinert, Hagen; Verena Schulte-Frohlinde (2001). Critical Properties of φ4-Theories. World Scientific. ISBN 981-02-4659-5. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. (readable online Archived 29 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine).

- Kogut, J.; Wilson, K (1974). "The Renormalization Group and the epsilon-Expansion". Phys. Rep. 12 (2): 75–199. Bibcode:1974PhR....12...75W. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(74)90023-4.

- Krieger, Martin H., Constitutions of matter : mathematically modelling the most everyday of physical phenomena, University of Chicago Press, 1996. Contains a detailed pedagogical discussion of Onsager's solution of the 2-D Ising Model.

- Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M., Statistical Physics Part 1, vol. 5 of Course of Theoretical Physics, Pergamon Press, 3rd Ed. (1994).

- Mussardo G., "Statistical Field Theory. An Introduction to Exactly Solved Models of Statistical Physics", Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Schroeder, Manfred R., Fractals, chaos, power laws : minutes from an infinite paradise, New York: W. H. Freeman, 1991. Very well-written book in "semi-popular" style—not a textbook—aimed at an audience with some training in mathematics and the physical sciences. Explains what scaling in phase transitions is all about, among other things.

- H. E. Stanley, Introduction to Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena (Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1971).

- Yeomans J. M., Statistical Mechanics of Phase Transitions, Oxford University Press, 1992.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Phase changes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Phase changes at Wikimedia Commons

- Interactive Phase Transitions on lattices Archived 5 July 2025 at the Wayback Machine with Java applets

- Universality classes from Sklogwiki

Phase transition

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Early Empirical Observations

Joseph Black's experiments in the 1760s provided the first systematic empirical evidence distinguishing heat absorbed during phase changes from that causing temperature rise in single phases. Observing that equal masses of ice and water, when heated, required significantly more thermal input to convert ice to water at 0°C than to elevate the temperature of already liquid water, Black quantified the latent heat of fusion for ice as approximately 144 times the heat capacity of water per degree Fahrenheit.[13] This demonstrated that during melting, temperature remained constant at the transition point despite continued heat application, challenging prevailing caloric theories and highlighting the energy barrier inherent to solid-liquid phase shifts.[14] Black extended these findings to vaporization, noting analogous latent heat during boiling, where water at 100°C absorbed substantial heat without temperature increase until fully converted to steam.[15] His 1762 lecture at the University of Glasgow formalized these observations, establishing calorimetry as a tool for probing phase boundaries and revealing that phase transitions involve discrete energy quanta tied to molecular rearrangements rather than continuous thermal expansion.[13] These results, derived from precise thermometer use post-1700s improvements, underscored the reproducibility of transition temperatures under constant pressure, laying empirical groundwork for later thermodynamic models.[16] Preceding Black, informal observations of phase phenomena—like the sharp freezing of water bodies or irregular heating in metallurgy—date to antiquity, but lacked quantification until reliable thermometry enabled controlled replication.[14] Black's work thus marked the onset of rigorous empiricism, confirming phase transitions as objective, measurable discontinuities in material properties driven by thermal energy thresholds.[15]Emergence of Theoretical Frameworks

The foundational thermodynamic framework for phase transitions was established by Josiah Willard Gibbs through his phase rule, derived in the papers "On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances" published in 1876 and 1878. This rule expresses the degrees of freedom in a multiphase system as , where denotes the number of independent chemical components and the number of phases, with the +2 accounting for temperature and pressure as variables under equilibrium conditions.[17] Gibbs' formulation enabled quantitative predictions of phase coexistence and stability, shifting analysis from purely empirical observations to rigorous thermodynamic constraints, though it remained phenomenological without microscopic underpinnings.[18] In 1933, Paul Ehrenfest advanced this framework by classifying phase transitions according to the order of discontinuities in thermodynamic derivatives. First-order transitions exhibit jumps in first-order derivatives of potentials like entropy or volume (manifesting as latent heat), while second-order transitions show discontinuities in second-order derivatives such as specific heat or compressibility, with continuous first derivatives.[19] This scheme highlighted the need to distinguish transition types based on thermodynamic singularities, influencing subsequent theoretical developments despite limitations in handling critical phenomena where higher derivatives diverge.[20] Lev Landau's 1937 theory marked a pivotal phenomenological advance for second-order transitions, introducing an order parameter to quantify symmetry breaking between disordered and ordered phases. Near the transition temperature , Landau expanded the free energy as , where the quadratic term drives the transition and higher even powers ensure stability; minimization yields above and below, predicting mean-field exponents like .[21] This symmetry-based approach, rooted in group theory, explained diverse transitions (e.g., ferromagnetic ordering) via universal free-energy forms, bridging thermodynamics to microscopic order while approximating fluctuations inadequately near criticality.[22]Key Milestones in 20th Century

In 1933, Paul Ehrenfest introduced a thermodynamic classification of phase transitions based on the order of discontinuities in derivatives of the free energy, distinguishing first-order transitions (discontinuous first derivatives like volume or entropy) from higher-order ones where lower derivatives remain continuous.[19] This framework, rooted in empirical observations of singularities in equations of state, provided an initial systematic categorization but later proved insufficient for capturing microscopic behaviors in continuous transitions.[23] Lev Landau advanced the field in 1937 with a general phenomenological theory for second-order phase transitions, employing the concept of an order parameter to describe symmetry breaking and expanding the Gibbs free energy in powers of this parameter near the critical point.[21] Landau's approach explained the emergence of new phases through minimization of the free energy functional, incorporating fluctuations via coupling to external fields, and applied successfully to phenomena like superfluidity in helium-4.[24] However, as a mean-field theory, it overestimated critical exponents by neglecting long-range correlations. A pivotal exact result came in 1944 when Lars Onsager solved the two-dimensional Ising model for ferromagnetic order-disorder transitions on a square lattice with zero external field, deriving the partition function and demonstrating a logarithmic divergence in specific heat without latent heat, alongside finite spontaneous magnetization below the critical temperature.[25] This solution exposed limitations in mean-field approximations like Landau's, as the critical exponents deviated from classical predictions (e.g., specific heat exponent α=0 with logarithmic singularity rather than mean-field jump), and underscored the role of dimensionality in transition behavior.[26] The 1960s saw preparatory scaling hypotheses from researchers like Leo Kadanoff and Benjamin Widom, positing universality in critical exponents across systems with similar symmetries and dimensions, but microscopic justification awaited Kenneth Wilson's 1971 formulation of the renormalization group transformation.[27] Wilson's method iteratively coarse-grains the system's degrees of freedom, revealing fixed points that govern infrared behavior and enabling computation of non-mean-field exponents via epsilon expansions near upper critical dimensions, thus resolving long-standing discrepancies in critical phenomena and earning him the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physics.[28] This development shifted focus from phenomenological models to scale-invariant microscopic theories, profoundly influencing understanding of continuous phase transitions.Fundamental Concepts

Definition and Thermodynamic Basis

A phase transition is a change in the thermodynamic state of a system from one phase to another, where a phase represents a homogeneous and mechanically stable configuration of matter with uniform physical properties throughout.[1] These transitions manifest as discontinuities or singularities in thermodynamic variables such as volume, entropy, or specific heat capacity, distinguishing them from smooth variations within a single phase.[4] Empirically observed examples include the melting of ice at 0°C and 1 atm, where solid and liquid water coexist, or the boiling of water at 100°C under the same conditions. The thermodynamic foundation of phase transitions rests on the minimization of the system's appropriate free energy potential, which dictates equilibrium stability. For processes at constant temperature and volume, the Helmholtz free energy (with as internal energy and as entropy) is minimized; at constant temperature and pressure, the Gibbs free energy (where is pressure and volume) governs stability./23:_Phase_Equilibria/23.02:_Gibbs_Energies_and_Phase_Diagrams) Stable phases correspond to global minima of these potentials, and a transition occurs when the free energies of competing phases become equal, enabling coexistence along a phase boundary in the phase diagram.[29] This equality implies that the chemical potentials of the phases match, as for a single-component system with particles.[4] Along coexistence curves, the Clapeyron equation relates the slope of the boundary to the enthalpy change and volume change of the transition, derived from the condition for both phases at equilibrium. Phase transitions introduce non-analyticities in the free energy, reflecting the emergence of collective order or structural reorganization driven by thermal fluctuations and interparticle interactions, as opposed to analytic continuations within phases.[30] This framework, rooted in classical thermodynamics, provides a causal explanation for why systems spontaneously shift phases: the drive toward free energy minimization favors the configuration with the lowest potential under prevailing conditions.[31]Order Parameters and Symmetry

In continuous phase transitions, the order parameter serves as a measurable quantity that is zero in the symmetric, disordered phase and acquires a nonzero expectation value in the ordered phase, quantifying the degree of ordering and distinguishing the phases thermodynamically.[32] This parameter must transform irreducibly under the system's symmetry group, ensuring that its expansion in the Landau free energy respects the underlying symmetries.[33] The appearance of a nonzero order parameter below the critical temperature signals spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB), where the ground state or thermal equilibrium state selects a configuration that lacks the full symmetry of the Hamiltonian or Lagrangian governing the system, even though all states collectively restore the symmetry.[34] In Landau theory, this is captured by expanding the free energy density as , where is the order parameter, , and ; above , the minimum is at (symmetric phase), while below , minima occur at finite , selecting a broken-symmetry direction.[32] Higher-order invariants, such as cubic terms (), can induce first-order transitions if present, but SSB remains tied to the stabilization of ordered states with reduced symmetry.[33] Specific examples illustrate the interplay: in ferromagnetic transitions, the magnetization acts as the order parameter, breaking continuous rotational symmetry in spin space (SO(3)) as aligns spontaneously along a direction, with magnitude near in mean-field approximation.[34] For the superfluid transition in helium-4, the complex scalar order parameter breaks U(1) phase symmetry, enabling off-diagonal long-range order and superflow.[32] In nematic liquid crystals, the tensorial order parameter breaks isotropic rotational symmetry (O(3)) down to uniaxial D_{\infty h}, reflecting molecular alignment without preferred direction reversal.[33] These cases highlight how the order parameter's representation under the symmetry group dictates the possible broken phases and associated Goldstone modes, which emerge as massless excitations restoring continuous symmetries in the low-temperature phase.[34] For first-order transitions, such as liquid-gas coexistence, an order parameter like the density difference jumps discontinuously, but SSB is absent in the strict sense, as both phases share the same symmetry group, with the transition driven by free-energy minimization rather than continuous symmetry reduction.[35] In contrast, SSB in continuous transitions underpins universality classes, where critical exponents depend on the dimensionality, range of interactions, and symmetry of the order parameter, as formalized in renormalization group theory beyond mean-field approximations.[32]States of Matter Involved

Phase transitions primarily involve transformations between the classical states of matter: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma.[36] In the solid state, atoms or molecules are arranged in a fixed, ordered lattice with definite shape and volume, resisting deformation under moderate forces.[37] The liquid state features particles in close proximity but with sufficient kinetic energy to flow and conform to container shapes while maintaining volume.[37] Gases consist of widely spaced particles moving freely, expanding to fill containers and exhibiting neither fixed shape nor volume.[37] Plasma, often regarded as the fourth classical state, comprises ionized particles—free electrons and positive ions—prevalent in high-temperature environments like stars or lightning, where thermal energy overcomes atomic binding.[36] These states are distinguished by macroscopic properties such as density, compressibility, and response to external fields, with transitions driven by changes in temperature, pressure, or composition.[6] Common transitions include melting (solid to liquid), occurring at the melting point where vibrational energy disrupts lattice order, as in ice to water at 0°C under standard pressure; freezing (liquid to solid), the reverse process; vaporization (liquid to gas), such as boiling water at 100°C; and condensation (gas to liquid).[38] Sublimation transforms solids directly to gas, exemplified by dry ice (solid CO₂) at -78.5°C, while deposition reverses this, as in frost formation.[38] Ionization converts gas to plasma via high energy input, and recombination yields gas from plasma.[38] Within solids, phase transitions can shift between polymorphic forms, like graphite to diamond under extreme pressure, without altering the overall solid state.[1] Beyond classical states, phase transitions access non-classical or exotic states under specialized conditions, such as Bose-Einstein condensates formed by cooling bosons to near absolute zero (achieved experimentally in 1995 with rubidium-87 atoms at 170 nK), where quantum coherence dominates.[39] Superfluids, like liquid helium-4 below 2.17 K, exhibit frictionless flow via transitions involving Cooper pairs.[40] These transitions highlight how varying thermodynamic parameters reveals diverse macroscopic behaviors, though classical solid-liquid-gas-plasma interconversions remain foundational to most observed phenomena.[6]Classifications

Ehrenfest Classification

The Ehrenfest classification, introduced by physicist Paul Ehrenfest in 1933, categorizes phase transitions based on the continuity of derivatives of the Gibbs free energy with respect to temperature and pressure .[20] The order of a transition is defined as the lowest integer such that the th-order derivative of is discontinuous at the transition point, while lower-order derivatives remain continuous.[19] This thermodynamic approach aimed to generalize the distinction between transitions like melting (discontinuous volume) and hypothetical continuous ones, without relying on microscopic details.[20] In first-order transitions, the first derivatives—entropy and volume —exhibit discontinuities, implying latent heat and a region of phase coexistence where both phases are stable.[6] Examples include the solid-liquid transition in water at 0°C and 1 atm, where volume jumps by about 9% upon melting, and the boiling of liquids.[5] These transitions involve hysteresis and supercooling or superheating effects due to the energy barrier between phases.[19] Second-order transitions feature continuous first derivatives but discontinuous second derivatives, such as the specific heat or the thermal expansion coefficient .[6] Ehrenfest initially applied this to the superconducting transition in mercury below 4.15 K at zero field, where resistivity drops discontinuously but entropy appears continuous (though later measurements refined this).[20] No latent heat occurs, and the transition is reversible without hysteresis.[5] Higher-order transitions () are defined similarly, with discontinuities in even higher derivatives, but empirical examples are scarce and often reclassified under modern schemes due to subtler singularities near critical points.[19] The Ehrenfest scheme provided a foundational phenomenological framework but overlooks divergences (rather than mere discontinuities) in derivatives at critical phenomena, as revealed by later statistical mechanics; for instance, the liquid-gas critical point at 31°C and 73.8 atm for CO₂ shows infinite susceptibility, not fitting neatly into finite-order discontinuities.[20] Despite these limitations, it remains a reference for distinguishing transitions by thermodynamic response functions.[19]First-Order and Continuous Transitions

First-order phase transitions feature a discontinuous change in the first derivatives of the thermodynamic potential, such as the Gibbs free energy G with respect to temperature (entropy S = -∂G/∂T) or pressure (volume V = ∂G/∂P), leading to latent heat Q = T ΔS and coexistence of phases separated by a finite energy barrier.[41][42] This discontinuity manifests as a jump in the order parameter, enabling hysteresis and metastability, where the system can persist in a higher-free-energy phase until nucleation overcomes the barrier./04%3A_Phase_Transitions/4.01%3A_First_order_phase_transitions) The Clapeyron equation dP/dT = ΔH / (T ΔV) governs the slope of the coexistence curve, with ΔH denoting the enthalpy of transition.[6] Prominent examples include the solid-liquid transition in water at the triple point (0.01°C, 611.657 Pa), where ice and liquid coexist with a volume contraction ΔV ≈ -1.6 × 10^{-6} m³/mol and latent heat of fusion 6.01 kJ/mol, and the liquid-vapor transition along the boiling curve up to the critical point (373.946°C, 22.064 MPa)./04%3A_Phase_Transitions/4.01%3A_First_order_phase_transitions) Solid-solid transformations, such as the α-to-γ phase change in iron at 912°C under ambient pressure, also qualify, involving atomic rearrangements with associated latent heats around 0.9 kJ/mol.[6] Continuous phase transitions, termed second-order in the Ehrenfest scheme, maintain continuity in first derivatives of G but exhibit discontinuities or divergences in second derivatives, such as specific heat C = -T ∂²G/∂T², without latent heat or phase coexistence./04%3A_Phase_Transitions/4.02%3A_Continuous_phase_transitions) The order parameter η evolves continuously from zero, often following mean-field power laws near the critical temperature T_c, with susceptibilities diverging as |T - T_c|^{-γ} where γ ≈ 1 in classical theory.[43] These transitions lack a barrier, proceeding via correlated fluctuations over diverging length scales ξ ~ |T - T_c|^{-ν}, underpinning universality classes beyond Ehrenfest's thermodynamic criteria.[5] Key instances encompass the ferromagnetic transition in iron at T_c = 1043 K, where spontaneous magnetization M vanishes continuously above the Curie point amid diverging magnetic susceptibility, and the superconducting-normal transition in mercury at 4.15 K under zero field, marked by zero-resistance onset without enthalpy jump./04%3A_Phase_Transitions/4.02%3A_Continuous_phase_transitions) The liquid-gas critical point in carbon dioxide at 31.0°C and 7.38 MPa exemplifies endpoint termination of first-order lines, yielding isotropic fluid with vanishing distinctions in density and compressibility divergence.[6] Unlike first-order cases, continuous transitions evade nucleation, driven instead by symmetry restoration through thermal agitation.[43]Quantum and Topological Classifications

Quantum phase transitions differ from thermal phase transitions by occurring at absolute zero temperature, where the absence of thermal fluctuations means that changes in the ground state are driven by quantum fluctuations tuned via a non-temperature control parameter, such as magnetic field strength, pressure, or electron density.[44] These transitions emerge as the system approaches a quantum critical point, where the ground-state energy landscape undergoes qualitative changes, often leading to enhanced quantum fluctuations that can influence finite-temperature properties over a fan-shaped quantum critical region in the phase diagram.[44] Quantum phase transitions are classified as continuous or first-order based on whether the order parameter changes discontinuously or through divergent correlation lengths, with continuous ones exhibiting universality classes analogous to but distinct from classical critical points due to the role of imaginary time in effective theories.[45] Prominent examples include the superconductor-to-normal metal transition under magnetic field suppression of Cooper pairs, observable in high-temperature superconductors like YBa₂Cu₃O₇₋δ at fields exceeding 100 T, and the metal-insulator transition in materials such as vanadium dioxide (VO₂) tuned by doping, where quantum fluctuations dictate the Mott or Anderson localization mechanisms.[46] In theoretical models, the Bose-Hubbard model at integer filling demonstrates a quantum phase transition from superfluid to Mott insulator at a critical hopping-to-interaction ratio U/t ≈ 5.8–16.7 depending on dimensionality, marking the onset of incompressible behavior without symmetry breaking in the strict T=0 limit but with precursors at low temperatures.[47] Experimental signatures include non-Fermi liquid behavior, such as linear resistivity versus temperature in heavy-fermion compounds like CeCu₆₋ₓAuₓ near x=0.1, attributed to proximity to antiferromagnetic quantum critical points.[48] Topological phase transitions delineate phases of matter distinguished not by spontaneous symmetry breaking or local order parameters, but by global topological invariants that remain robust against smooth deformations, provided underlying symmetries like time-reversal or particle-hole are preserved.[49] These transitions typically involve the closing and reopening of an energy gap at high-symmetry points in momentum space, driven by tuning parameters that alter band topology, and evade conventional Landau-Ginzburg descriptions due to the absence of a dual scalar order parameter pairing trivial and nontrivial sectors.[49] Classification schemes for topological phases and their transitions follow the Altland-Zirnbauer (AZ) tenfold way, categorizing systems into 10 symmetry classes (A, AI, AII, AIII, BDI, C, CI, CII, D, DIII) based on combinations of time-reversal (TRS), particle-hole (PHS), and chiral (S) symmetries, with topological invariants computed via K-theory or homotopy groups that predict the number and nature of gapless boundary modes.[50] In two dimensions, the integer quantum Hall effect exemplifies a topological transition where plateaus in Hall conductance σ_xy = n e²/h (n integer) separate Chern insulator phases, with transitions occurring via dissipationless edge state reconfiguration under varying magnetic field or filling factor, as realized in GaAs heterostructures at cryogenic temperatures below 1 K.[51] Three-dimensional topological insulators, such as Bi₂Se₃, undergo transitions to trivial insulators by breaking TRS with magnetic doping, closing the bulk gap while preserving helical surface states protected by Z₂ invariants.[52] Recent extensions include hybrid classifications for interacting systems, where fractional topological order in fractional quantum Hall states at filling ν=1/3 introduces anyon excitations, with phase boundaries mapped via entanglement spectroscopy in cold-atom realizations.[53] These classifications underscore causal distinctions from symmetry-broken phases, as topological protection arises from band geometry rather than energetic minimization alone.[54]Types of Phase Transitions

Structural and Crystallographic Transitions

Structural phase transitions refer to changes in the arrangement of atoms within a crystalline solid that alter the crystal symmetry or lattice structure, typically induced by variations in temperature, pressure, or composition, without changing the material's chemical identity.[55] These transitions occur between distinct solid phases and are distinguished from liquid-solid or gas-solid changes by the preservation of long-range order, though the specific symmetry and topology of that order evolve.[56] Empirical observations, such as shifts in X-ray diffraction patterns, confirm these alterations, reflecting causal mechanisms rooted in minimizing free energy through atomic rearrangements.[57] Crystallographic transitions specifically involve modifications to the unit cell parameters, space group symmetry, or coordination environments, often manifesting as distortions like tilting of polyhedra or shear deformations.[58] They can proceed via two primary mechanisms: displacive, where atoms undergo collective, diffusionless shifts with minimal bond breaking, leading to continuous or nearly continuous changes; or reconstructive, involving bond rupture, atomic diffusion, and nucleation-growth processes that disrupt and rebuild the lattice topology.[56] Displacive mechanisms predominate in transitions preserving structural similarity, such as martensitic transformations, while reconstructive ones require thermal activation to overcome energy barriers associated with diffusion, as evidenced by kinetic studies showing hysteresis and latent heat release.[59] Order-disorder subtypes, a variant of displacive transitions, arise from randomizing positional or orientational degrees of freedom, like cation site occupancy in alloys.[60] In metals, prominent examples include the allotropic transformation in tin from white (tetragonal) to gray (diamond cubic) at 13.2°C, a reconstructive first-order transition driven by density changes and volume expansion of 27%, which proceeds via nucleation and growth due to the incompatibility of lattices.[56] Iron exhibits multiple structural shifts, such as body-centered cubic (α) to face-centered cubic (γ) at 912°C, involving reconstructive diffusion to accommodate packing efficiency under thermal expansion.[61] Martensitic transitions in steels, by contrast, are displacive, featuring rapid, shear-dominated austenite-to-martensite conversion below 727°C, with variants oriented by habit planes to minimize strain energy, as quantified by invariant line strain analysis.[62] Ceramics display analogous transitions, such as the displacive ferroelectric shift in barium titanate (BaTiO3) from paraelectric cubic to tetragonal at 120°C, where off-center Ti displacements break inversion symmetry, enabling piezoelectricity; this is continuous near the Curie point, with soft phonon modes signaling instability.[63] Zirconia (ZrO2) undergoes a reconstructive tetragonal-to-monoclinic transition upon cooling below 1170°C, generating 3-5% volume expansion that induces cracking unless stabilized, as in yttria-partially stabilized variants; the mechanism involves oxygen coordination changes from 7 to 8, confirmed by high-resolution electron microscopy.[64] In silicates like quartz, the α-β inversion at 573°C is displacive, rotating SiO4 tetrahedra to alter trigonal symmetry, with no diffusion required, highlighting how lattice vibrations couple to macroscopic strain.[55] These transitions underpin materials functionality, influencing mechanical toughness via transformation toughening in ceramics or enabling shape-memory effects in alloys through reversible displacive paths.[65] Pressure-induced variants, such as isosymmetric second-order shifts increasing coordination (e.g., in silicates at gigapascal ranges), demonstrate how compressive stress alters bonding preferences without symmetry loss, as revealed by diamond-anvil cell experiments.[66] Source credibility in this domain favors experimental crystallography from peer-reviewed journals over theoretical models alone, given occasional discrepancies between simulations and observed kinetics in reconstructive cases.[67]Magnetic and Superconducting Transitions

Magnetic phase transitions occur when the magnetic ordering of spins in a material changes with temperature or external fields, often exhibiting critical behavior near the transition point. A prominent example is the ferromagnetic-to-paramagnetic transition at the Curie temperature , above which spontaneous magnetization vanishes and the material behaves as a paramagnet. For pure iron, K; cobalt has K; and nickel K.[68] These transitions are typically second-order, characterized by a continuous order parameter— the magnetization —that follows a power-law decay below , with in three dimensions from Ising universality class simulations, deviating from mean-field .[69] Antiferromagnetic transitions occur at the Néel temperature , where staggered magnetization orders antiparallel spins; for instance, in MnO, K. Ferrimagnetic materials like magnetite (FeO) show transitions at K, involving unequal antiparallel sublattices.[70] These magnetic transitions involve symmetry breaking in spin orientations, with susceptibility diverging as near , where experimentally for ferromagnets.[69] Fluctuations become long-range correlated, leading to critical phenomena observable in neutron scattering, revealing spin waves below that soften at the transition. In applied fields, first-order transitions can emerge, as in manganites where colossal magnetoresistance accompanies metal-insulator changes.[71] Superconducting phase transitions mark the onset of zero electrical resistance and the Meissner effect—expulsion of magnetic fields—below a critical temperature . Discovered in mercury at K in 1911, conventional superconductors follow Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory, where electrons form Cooper pairs via phonon-mediated attraction, opening an energy gap .[72][73] The transition is second-order in BCS, with specific heat showing a discontinuity at , and exponential tail below. High-temperature superconductors, such as YBaCuO with K and HgBaCaCuO reaching 134 K under pressure, deviate from BCS pairing mechanisms, possibly involving magnetic fluctuations.[73] In superconductors, the order parameter is a complex scalar representing the density of Cooper pairs, with near in Ginzburg-Landau phenomenology. Quantum phase transitions in superconductors occur at under doping or pressure, separating superconducting from insulating states, as observed in cuprates where domes with carrier concentration.[74] Critical fields , bound the phase, with type-I showing abrupt Meissner expulsion and type-II forming vortices. Recent studies confirm field-induced transitions within superconducting states, like in CeRhAs at K with T.[75]Transitions in Mixtures and Fluids