Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Real gas

View on Wikipedia| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

Real gases are non-ideal gases whose molecules occupy space and have interactions; consequently, they do not adhere to the ideal gas law. To understand the behaviour of real gases, the following must be taken into account:

- compressibility effects;

- variable specific heat capacity;

- van der Waals forces;

- non-equilibrium thermodynamic effects;

- issues with molecular dissociation and elementary reactions with variable composition

For most applications, such a detailed analysis is unnecessary, and the ideal gas approximation can be used with reasonable accuracy. On the other hand, real-gas models have to be used near the condensation point of gases, near critical points, at very high pressures, to explain the Joule–Thomson effect, and in other less usual cases. The deviation from ideality can be described by the compressibility factor Z.

Models

[edit]

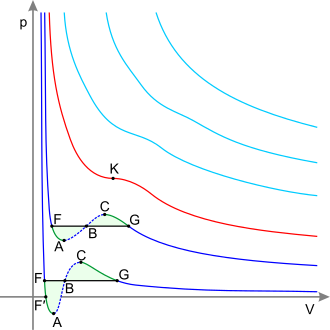

Dark blue curves – isotherms below the critical temperature. Green sections – metastable states.

The section to the left of point F – normal liquid.

Point F – boiling point.

Line FG – equilibrium of liquid and gaseous phases.

Section FA – superheated liquid.

Section F′A – stretched liquid (p<0).

Section AC – analytic continuation of isotherm, physically impossible.

Section CG – supercooled vapor.

Point G – dew point.

The plot to the right of point G – normal gas.

Areas FAB and GCB are equal.

Red curve – Critical isotherm.

Point K – critical point.

Light blue curves – supercritical isotherms

Van der Waals model

[edit]Real gases are often modeled by taking into account their molar weight and molar volume

or alternatively:

Where p is the pressure, T is the temperature, R the ideal gas constant, and Vm the molar volume. a and b are parameters that are determined empirically for each gas, but are sometimes estimated from their critical temperature (Tc) and critical pressure (pc) using these relations:

The constants at critical point can be expressed as functions of the parameters a, b:

With the reduced properties , , the equation can be written in the reduced form:

Redlich–Kwong model

[edit]

The Redlich–Kwong equation is another two-parameter equation that is used to model real gases. It is almost always more accurate than the van der Waals equation, and often more accurate than some equations with more than two parameters. The equation is

or alternatively:

where a and b are two empirical parameters that are not the same parameters as in the van der Waals equation. These parameters can be determined:

The constants at critical point can be expressed as functions of the parameters a, b:

Using , , the equation of state can be written in the reduced form: with

Berthelot and modified Berthelot model

[edit]The Berthelot equation (named after D. Berthelot)[1] is very rarely used,

but the modified version is somewhat more accurate

Dieterici model

[edit]This model (named after C. Dieterici[2]) fell out of usage in recent years

with parameters a, b. These can be normalized by dividing with the critical point state[note 1]:which casts the equation into the reduced form:[3]

Clausius model

[edit]The Clausius equation (named after Rudolf Clausius) is a very simple three-parameter equation used to model gases.

or alternatively:

where

where Vc is critical volume.

Virial model

[edit]The Virial equation derives from a perturbative treatment of statistical mechanics.

or alternatively

where A, B, C, A′, B′, and C′ are temperature dependent constants.

Peng–Robinson model

[edit]Peng–Robinson equation of state (named after D.-Y. Peng and D. B. Robinson[4]) has the interesting property being useful in modeling some liquids as well as real gases.

Wohl model

[edit]

The Wohl equation (named after A. Wohl[5]) is formulated in terms of critical values, making it useful when real gas constants are not available, but it cannot be used for high densities, as for example the critical isotherm shows a drastic decrease of pressure when the volume is contracted beyond the critical volume.

or:

or, alternatively:

where where , , are (respectively) the molar volume, the pressure and the temperature at the critical point.

And with the reduced properties , , one can write the first equation in the reduced form:

Beattie–Bridgeman model

[edit][6] This equation is based on five experimentally determined constants. It is expressed as

where

This equation is known to be reasonably accurate for densities up to about 0.8 ρcr, where ρcr is the density of the substance at its critical point. The constants appearing in the above equation are available in the following table when p is in kPa, Vm is in , T is in K and [7]

| Gas | A0 | a | B0 | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 131.8441 | 0.01931 | 0.04611 | −0.001101 | 4.34×104 |

| Argon, Ar | 130.7802 | 0.02328 | 0.03931 | 0.0 | 5.99×104 |

| Carbon dioxide, CO2 | 507.2836 | 0.07132 | 0.10476 | 0.07235 | 6.60×105 |

| Ethane, C2H6 | 595.791 | 0.05861 | 0.09400 | 0.01915 | 90.00×104 |

| Helium, He | 2.1886 | 0.05984 | 0.01400 | 0.0 | 40 |

| Hydrogen, H2 | 20.0117 | −0.00506 | 0.02096 | −0.04359 | 504 |

| Methane, CH4 | 230.7069 | 0.01855 | 0.05587 | -0.01587 | 12.83×104 |

| Nitrogen, N2 | 136.2315 | 0.02617 | 0.05046 | −0.00691 | 4.20×104 |

| Oxygen, O2 | 151.0857 | 0.02562 | 0.04624 | 0.004208 | 4.80×104 |

Benedict–Webb–Rubin model

[edit]The BWR equation,

where d is the molar density and where a, b, c, A, B, C, α, and γ are empirical constants. Note that the γ constant is a derivative of constant α and therefore almost identical to 1.

Thermodynamic expansion work

[edit]The expansion work of the real gas is different than that of the ideal gas by the quantity .

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ D. Berthelot in Travaux et Mémoires du Bureau international des Poids et Mesures – Tome XIII (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1907)

- ^ C. Dieterici, Ann. Phys. Chem. Wiedemanns Ann. 69, 685 (1899)

- ^ Pippard, Alfred B. (1981). Elements of classical thermodynamics: for advanced students of physics (Repr ed.). Cambridge: Univ. Pr. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-521-09101-5.

- ^ Peng, D. Y. & Robinson, D. B. (1976). "A New Two-Constant Equation of State". Industrial and Engineering Chemistry: Fundamentals. 15: 59–64. doi:10.1021/i160057a011. S2CID 98225845.

- ^ A. Wohl (1914). "Investigation of the condition equation". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 87: 1–39. doi:10.1515/zpch-1914-8702. S2CID 92940790.

- ^ Yunus A. Cengel and Michael A. Boles, Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2010, ISBN 007-352932-X

- ^ Gordan J. Van Wylen and Richard E. Sonntage, Fundamental of Classical Thermodynamics, 3rd ed, New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1986 P46 table 3.3

- ^ The critical state can be calculated by starting with , and taking the derivative with respect to . The equation is a quadratic equation in , and it has a double root precisely when .

Further reading

[edit]- Kondepudi, D. K.; Prigogine, I. (1998). Modern thermodynamics: From heat engines to dissipative structures. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-97393-5.

- Hsieh, J. S. (1993). Engineering Thermodynamics. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-275702-7.

- Walas, S. M. (1985). Fazovyje ravnovesija v chimiceskoj technologii v 2 castach. Butterworth Publishers. ISBN 978-0-409-95162-2.

- Aznar, M.; Silva Telles, A. (1997). "A Data Bank of Parameters for the Attractive Coefficient of the Peng-Robinson Equation of State". Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering. 14 (1): 19–39. doi:10.1590/S0104-66321997000100003.

- Rao, Y. V. C (2004). An introduction to thermodynamics. Universities Press. ISBN 978-81-7371-461-0.

- Xiang, H. W. (2005). The Corresponding-States Principle and its Practice: Thermodynamic, Transport and Surface Properties of Fluids. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-045904-2.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}p_{c}&={\frac {a}{27b^{2}}},&V_{m,c}&=3b,\\[2pt]T_{c}&={\frac {8a}{27bR}},&Z_{c}&={\frac {3}{8}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/452744ebd479362fd083d21e706fccc095309e62)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&=0.42748\,{\frac {R^{2}{T_{\text{c}}}^{\frac {5}{2}}}{p_{\text{c}}}},\\[2pt]b&=0.08664\,{\frac {RT_{\text{c}}}{p_{\text{c}}}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9e2fbac2964b81310524782791854a1e0e1833d6)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}p_{c}&={\left[{\frac {({\sqrt[{3}]{2}}-1)^{7}}{3}}\,R\,{\frac {a^{2}}{b^{5}}}\right]}^{1/3},&V_{m,c}&={\frac {b}{{\sqrt[{3}]{2}}-1}},\\[4pt]T_{c}&={\left[3{\left({\sqrt[{3}]{2}}-1\right)}^{2}{\frac {a}{bR}}\right]}^{2/3},&Z_{c}&={\frac {1}{3}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0d3bba92f778db56afed69f87d00a9e9ca1e0904)

![{\displaystyle b'={\sqrt[{3}]{2}}-1\approx 0.26}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/578b7130159a520fdd079b4a4857ef08fc6e898f)

![{\displaystyle p={\frac {RT}{V_{\text{m}}}}\left[1+{\frac {9}{128}}\cdot {\frac {p}{p_{c}}}\cdot {\frac {T_{c}}{T}}\left(1-6{\frac {T_{\text{c}}^{2}}{T^{2}}}\right)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b3519e2ba24083ffe59e3afdc6488152dad36192)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&={\frac {27R^{2}T_{\text{c}}^{3}}{64p_{\text{c}}}},\\[4pt]b&=V_{\text{c}}-{\frac {RT_{\text{c}}}{4p_{\text{c}}}},\\[4pt]c&={\frac {3RT_{\text{c}}}{8p_{\text{c}}}}-V_{\text{c}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4d89d1316a2120bcd4601ddb0800fad5f643d0b2)

![{\displaystyle pV_{\text{m}}=RT\left[1+{\frac {B(T)}{V_{\text{m}}}}+{\frac {C(T)}{V_{\text{m}}^{2}}}+{\frac {D(T)}{V_{\text{m}}^{3}}}+\cdots \right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c9eebec775b547603397c735dda026641ec5e853)

![{\displaystyle pV_{\text{m}}=RT\left[1+B'(T)p+C'(T)p^{2}+D'(T)p^{3}+\cdots \right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6a36ae0565ecdfd65defd0d41902045ee3d7b6dd)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}a&=6p_{\text{c}}T_{\text{c}}V_{\text{m,c}}^{2},&b&={\frac {V_{\text{m,c}}}{4}},\\[2pt]c&=4p_{\text{c}}T_{\text{c}}^{2}V_{\text{m,c}}^{3}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b07e2253de765b9d529d43df6a4036c8bc2a1b17)

![{\displaystyle p=RTd+d^{2}\left(RT(B+bd)-\left(A+ad-a\alpha d^{4}\right)-{\frac {1}{T^{2}}}\left[C-cd\left(1+\gamma d^{2}\right)\exp \left(-\gamma d^{2}\right)\right]\right)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/08d43caaf20d4f8946f7449bba37b3849305619e)