Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Burrowing parrot

View on Wikipedia

| Burrowing parrot | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Cyanoliseus |

| Species: | C. patagonus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cyanoliseus patagonus (Vieillot, 1818)

| |

| |

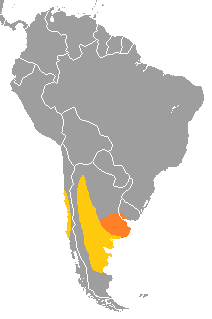

| yellow is nesting area, orange is area of seasonal food migrations | |

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus), also known as the burrowing parakeet or the Patagonian conure, is a species of parrot native to Argentina and Chile. It belongs to the monotypic genus Cyanoliseus, with four subspecies that are currently recognized.

The burrowing parrot is unmistakable with a distinctive white eye ring, white breast marking, olive green body colour, and brightly coloured underparts. Named for their nesting habits, burrowing parrots excavate elaborate burrows in cliff faces and ravines in order to rear their chicks. They inhabit dry, open country up to 2000 m in elevation.[2] Once abundant across Argentina and Chile, burrowing parrot populations have been in decline due to exploitation and persecution.[2]

Taxonomy, phylogeny and systematics

[edit]

The burrowing parrot was first described in 1818 by Louis Pierre Vieillot as Psittacus patagonus.[3] The genus was later renamed Cyanoliseus by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1854.[4]

The burrowing parrot is the only member of the genus Cyanoliseus, making it monotypic. Together with other genera of long-tailed New World parrots, Cyanoliseus is a part of the Tribe Arini, which in turn is a part of the subfamily Arinae, or Neotropical parrots, in the family of true parrots, Psittacidae. The closest relative of the burrowing parrot is thought to be the Nanday parakeet.[5][6]

There are four recognized subspecies, however the subspecies C. p. conlara is considered doubtfully distinct:[7]

- C. p. patagonus (Vieillot) is the nominate subspecies found in central to southeast Argentina, with some migrants reaching southern Uruguay[2]

- C. p. andinus (Dabbene and Lillo) is found in northwest Argentina, from Salta to San Juan.[2] Plumage is duller than the nominate C. p. patagonus, with much fainter markings.[8] This population is estimated to be approximately 2000 individuals.[9]

- C. p. conlara (Nores and Yzurieta) can be found in San Luis, between the ranges of C. p. patagonus and C. p. andinus, and is visually similar to C. p. patagonus except for a darker breast, suggesting that C. p. conlara may be a hybrid instead of a distinct subspecies[7][9]

- C. p. bloxami (Olson), formerly C. p. byroni, also known as the Greater Patagonian Conure,[10] is the Chilean sub-population. Formerly occurring from Atacama to Valdivia, this subspecies is now restricted to isolated populations in central Chile in the O'Higgins, Maule and Atacama regions.[2] Unlike the nominate subspecies, the white breast markings of this subspecies are prominent and extend across the whole breast, and the yellow underparts and red abdomen are much brighter.[8] It is larger in size than C. p. patagonus at 315-390g.[10] Populations are currently estimated at 5000-6000 individuals.[9]

Another subspecies, C. p. whitleyi (Kinnear), was described but has since been determined to be an aviary hybrid between a burrowing parrot and a species from the genus Aratinga or possibly Primolius.[2][8]

A study on mitochondrial DNA in burrowing parrots suggests that the species originated in Chile, the Argentinian populations arising during the Late Pleistocene from "a single migration event across the Andes, which gave rise to all extant Argentinean mitochondrial lineages".[9] The Andes represent a strong geographical barrier, thus isolating the Chilean population, which were found to be genetically and phenotypically distinct from the Argentinian populations.[9] This study found no support for C. p. conlara as a subspecies, and instead suggests a hybrid zone between the C. p. patagonus and C. p. andinus ranges where C. p. conlara represents the hybrid phenotype.

Description

[edit]Adults measure 39–52 cm in length, with a wingspan of 23–25 cm and a long, graduated tail that can range from 21 to 26 cm. Burrowing parrots are slightly sexually dimorphic, with males being slightly larger and weighing approximately 253-340 g, while females weigh 227-304 g,[2][8] making it the largest member of the group of New World parakeet species commonly known as conures.[11]

The burrowing parrot is a distinctive parrot; it has a bare, white eye ring and post-ocular patch, its head and upper back are olive-brown, and its throat and breast are grey-brown with a whitish pectoral marking, which is variable and rarely extends across the whole breast.[2][8] The lower thighs and the center of the abdomen are orange-red, and it is thought that the extent and hue of the red plumage indicates the quality of the individual as a breeding partner and parent.[12] The lower back, upper thighs, rump, vent and flanks are yellow, and the wing coverts olive green.[2] The tail is olive green with a blue caste when viewed from above and brown from below.[8] The burrowing parrot has a grey bill and yellow-white iris with pink legs.[8] Immature birds look like adults but with a horn coloured upper mandible patch and a pale grey iris.[2][8]

While both sexes look visually similar to the human eye, the burrowing parrot is sexually dichromatic. Males tend to have significantly redder and larger abdominal red patches,[12] and both sexes look different under UV light, with males have brighter green feathers and females having brighter blue feathers.[13]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The burrowing parrot can be found in much of Argentina, and there are isolated populations in central Chile.[2] In the winter, birds in central and southern Argentina may migrate north as far as southern Uruguay, making them austral migrants, while Chilean birds migrate vertically down slope to avoid colder altitudes.[8] Movements in the populations of northwestern Argentina are also known to occur according to food availability.[8]

The burrowing parrot prefers dry, open country, particularly in the vicinity of water courses, up to 2000 m in elevation.[2] Habitats include montane grassy shrubland, Patagonian steppes, arid lowland, woodland savanna, and the plains of the Gran Chaco.[2][8] They may also inhabit farmland and the edges of urban areas.[2]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]Diet

[edit]The diet of the burrowing parrot comprises seeds, berries, fruits, and possibly vegetable matter,[8] and they can be seen feeding on the ground or in trees and shrubs.[2] Their diet varies seasonally, with fruit consumption peaking during Argentina's summer (December–February), where one study found that fruit makes up 2% of their crop contents in November–December, 74% in January, 25% in February, 35%,in March and 8% in April.[8] Specifically, burrowing parrots have been observed feeding on the fruit from various species such as the red crowberry (Empetrum rubrum), Chilean palo verde (Geoffroea decorticans), Lycium salsum, pepper trees (Schinus sp.), Prosopis sp., Discaria sp., as well as cacti.[2] In the winter, the burrowing parrot feeds predominantly on seeds from cultivated crops and wild plants such as thistles, as well as the Patagonian oak (Nothofagus obliqua) and the Carboncillo (Cordia decandra) in the Chilean foothills.[2]

Reproduction

[edit]Best known for its nesting habits, the burrowing parrot excavates industrious burrows in limestone or sandstone cliff faces, often in ravines. These burrows can be as much as 3 m deep into a cliff-face, connecting with other tunnels to create a labyrinth, ending in a nesting chamber.[8] Breeding pairs will reuse burrows from previous years but may enlarge them.[14] They nest in large colonies, some of the largest ever recorded for parrots, which is thought to reduce predation.[14] The parrots tend to select larger, taller ravines, allowing for larger colonies and higher burrows and resulting in higher breeding success.[14]

In the absence of acceptable ravines or cliffs to use as nesting sites, burrowing parrots will use anthropogenic substrates such as quarries, wells and pits.[15] Rarely, they have been known to nest in tree cavities.[16]

Studies have shown that burrowing parrots are both socially and genetically monogamous.[17] The breeding season begins in September, and eggs are laid up to December, with two up to five eggs laid per clutch.[2] The incubation period is 24–25 days, where the female is the sole incubator while the male provides for her.[18] Eggs hatch asynchronously, and mortality is higher for fourth and fifth chicks in a clutch.[18] Both parents care for the chicks. Chicks begin to fledge in late December until February, approximately eight weeks after hatching,[8] and the fledglings depend on their parents for up to four months.[18]

Thermoregulation

[edit]In order to cope with an unpredictable climate, burrowing parrots increase their body mass and decrease their basal metabolic rate (BMR) in the winter in order to conserve energy, insulate against cold ambient temperatures and to survive reductions in food availability, in concurrence with other birds found in the southern hemisphere.[19]

Status and relationship to humans

[edit]

The burrowing parrot currently has an overall conservation status of least concern according to the IUCN Red List, but populations are currently declining, due to exploitation for the wildlife trade and persecution as a crop pest.[20] Their nesting habits make them particularly vulnerable to human disturbances and habitat degradation.[2] It is nonetheless currently listed under Appendix II of CITES, allowing for international trade,[2] but the endangered C. p. bloxami Chilean subspecies is on the Chilean national vertebrate red list.[9]

The burrowing parrot was officially named as a crop pest in Argentina in 1984, leading to increased persecution.[2] Their status as a crop pest has excluded them protection under Argentina's ban on wildlife trade,[2] however the province of Río Negro has deemed population reductions sufficient and banned hunting and trade of the burrowing parrot as of 2004.[9] Studies have shown that the effects of crop predation by burrowing parrots is economically insignificant.[21] Additionally, birds of the Chilean subspecies (C. p. bloxami) have been hunted for feast-day in Chile.[2]

The Mapuche people of the province of Neuquén in the Patagonian Andes celebrate the annual fledging of burrowing parrots with a festival.[22]

Aviculture

[edit]The burrowing parrot, commonly called the Patagonian conure in aviculture, is a popular companion parrot. It is known for being playful, gentle and affectionate with humans, even cuddly when tame - it can also learn to talk and mimic sounds from its environment. As a large parakeet, it requires plenty of living space and the opportunity to fly on a regular basis in order to thrive.[23] The maximum verified lifespan for this species in captivity is 19.5 years, however plausible claims of burrowing parrots living up to 34.1 years have also been reported.[24]

The subspecies typically found in aviculture is the nominate ssp., Cyanoliseus patagonus patagonus - also known as the lesser Patagonian conure. Tens of thousands of burrowing parakeets were previously removed from the wild and exported for the pet trade, but most birds available for purchase as pets are nowadays captive-bred.[25]

References

[edit]![]() Media related to Cyanoliseus patagonus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cyanoliseus patagonus at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Cyanoliseus patagonus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T22685779A132255876. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22685779A132255876.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Collar, Nigel; Boesman, Peter F. D. (2020-03-04), Billerman, Shawn M.; Keeney, Brooke K.; Rodewald, Paul G.; Schulenberg, Thomas S. (eds.), "Burrowing Parakeet (Cyanoliseus patagonus)", Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, doi:10.2173/bow.burpar.01, S2CID 241425121, retrieved 2020-10-15

- ^ Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine, etc. Vol. t.25 (1817) (Nouv. éd. presqu' entièrement refondue et considérablement angmentée. ed.). Paris: Chez Deterville. 1817. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.20211.

- ^ Bonaparte, Charles Lucien (1857). Opera ornithologica. Vol. 2. Paris?.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Tavares, Erika Sendra; Baker, Allan J.; Pereira, Sérgio Luiz; Miyaki, Cristina Yumi (2006-06-01). "Phylogenetic Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Parrots (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae: Arini) Inferred from Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Sequences". Systematic Biology. 55 (3): 454–470. doi:10.1080/10635150600697390. ISSN 1076-836X. PMID 16861209.

- ^ Wright, Timothy F.; Schirtzinger, Erin E.; Matsumoto, Tania; Eberhard, Jessica R.; Graves, Gary R.; Sanchez, Juan J.; Capelli, Sara; Müller, Heinrich; Scharpegge, Julia; Chambers, Geoffrey K.; Fleischer, Robert C. (2008-07-24). "A Multilocus Molecular Phylogeny of the Parrots (Psittaciformes): Support for a Gondwanan Origin during the Cretaceous". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 25 (10): 2141–2156. doi:10.1093/molbev/msn160. ISSN 1537-1719. PMC 2727385. PMID 18653733.

- ^ a b Forshaw, Joseph Michael (2010). Parrots of the world. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3620-8. OCLC 705945316.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Forshaw, Joseph M. (1989). Parrots of the World (3rd ed.). Willoughby, NSW, Australia: Lansdowne Editions. pp. 470–472. ISBN 0-7018-2800-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Masello, Juan F.; Quillfeldt, Petra; Munimanda, Gopi K.; Klauke, Nadine; Segelbacher, Gernot; Schaefer, H. Martin; Failla, Mauricio; Cortes, Maritza; Moodely, Yoshan (15 June 2011). "The high Andes, gene flow and a stable hybrid zone shape the genetic structure of a wide-ranging South American parrot". Frontiers in Zoology. 8: 16. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-8-16. PMC 3142489. PMID 21672266.

- ^ a b "Patagonian Conure". World Parrot Trust. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Types of conures | with pictures! - Psittacology". Psittacology. 13 April 2020.

- ^ a b MASELLO, Juan F.; PAGNOSSIN, María Luján; LUBJUHN, Thomas; QUILLFELDT, Petra (2004-06-18). "Ornamental non-carotenoid red feathers of wild burrowing parrots". Ecological Research. 19 (4): 421–432. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1703.2004.00653.x. ISSN 0912-3814. S2CID 6123165.

- ^ Masello, Juan F.; Lubjuhn, T.; Quillfeldt, Petra (August 2009). "Hidden dichromatism in Burrowing Parrots Cyanoliseus patagonus as revealed by spectrometric colour analysis". Hornero. 24: 47. doi:10.56178/eh.v24i1.729. hdl:20.500.12110/hornero_v024_n01_p047. S2CID 55392503 – via Research Gate.

- ^ a b c Ramirez-Herranz, Myriam; Rios, Rodrigo S.; Vargas-Rodriguez, Renzo; Novoa-Jerez, Jose-Enrique; Squeo, Francisco A. (2017-04-26). "The importance of scale-dependent ravine characteristics on breeding-site selection by the Burrowing Parrot, Cyanoliseus patagonus". PeerJ. 5 e3182. doi:10.7717/peerj.3182. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5408729. PMID 28462019.

- ^ Tella, José L.; Canale, Antonela; Carrete, Martina; Petracci, Pablo; Zalba, Sergio M. (2014). "Anthropogenic Nesting Sites Allow Urban Breeding in Burrowing ParrotsCyanoliseus patagonus". Ardeola. 61 (2): 311–321. doi:10.13157/arla.61.2.2014.311. hdl:11336/21787. ISSN 0570-7358. S2CID 84131010.

- ^ Zungu, Manqoba M.; Brown, Mark; Downs, Colleen T. (2018). "Seasonal thermoregulation in the burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus)". Journal of Thermal Biology. 38 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2012.10.001. ISSN 0306-4565. PMID 24229804.

- ^ Masello, Juan F.; Sramkova, Anna; Quillfeldt, Petra; Epplen, Jörg Thomas; Lubjuhn, Thomas (24 July 2002). "Genetic monogamy in burrowing parrots Cyanoliseus patagonus?". Journal of Avian Biology. 33 (1): 99–103. doi:10.1034/j.1600-048x.2002.330116.x. ISSN 0908-8857.

- ^ a b c Masello, Juan F.; Quillfeldt, Petra (2002). "Chick Growth and Breeding Success of the Burrowing Parrot". The Condor. 104 (3): 574. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2002)104[0574:cgabso]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0010-5422.

- ^ Zungu, Manqoba M.; Brown, Mark; Downs, Colleen T. (January 2013). "Seasonal thermoregulation in the burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus)". Journal of Thermal Biology. 38 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2012.10.001. ISSN 0306-4565. PMID 24229804.

- ^ International), BirdLife International (BirdLife (2018-08-07). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Cyanoliseus patagonus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2020-10-15.

- ^ Sánchez, Rocío; Ballari, Sebastián A.; Bucher, Enrique H.; Masello, Juan F. (2016-06-27). "Foraging by burrowing parrots has little impact on agricultural crops in northeastern Patagonia, Argentina". International Journal of Pest Management. 62 (4): 326–335. doi:10.1080/09670874.2016.1198061. hdl:11336/129774. ISSN 0967-0874. S2CID 89257448.

- ^ Masello, Juan F.; Quillfeldt, Petra (2004). "News from El Cóndor, Patagonia,Argentina". PsittaScene.

- ^ "Patagonian Conure Health, Personality, Colors and Sounds". 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Patagonian conure (Cyanoliseus patagonus) longevity, ageing, and life history". The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Patagonian Conure Fact Sheet". 2 January 2013.

External links

[edit]Burrowing parrot

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Systematics

Etymology and Classification

The common name burrowing parrot (also rendered as burrowing parakeet) originates from the species' specialized nesting strategy, whereby pairs and colonies excavate extensive tunnels into vertical cliff faces, riverbanks, or earthen escarpments to rear their young, a trait uncommon among parrots.[2] An alternative vernacular name, Patagonian conure, highlights its core range across the arid and semi-arid landscapes of Patagonia in southern South America.[7] The binomial Cyanoliseus patagonus stems from the species' initial scientific description by French ornithologist Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1818, originally classified as Psittacus patagonus.[8] The genus Cyanoliseus was formalized in 1854 by Charles Lucien Bonaparte, who reassigned the species to this newly erected taxon, establishing it as a monotypic genus with no other included members.[2] The specific epithet patagonus directly references Patagonia, the ecoregion encompassing much of the bird's native habitat in Argentina and Chile.[9] Taxonomically, C. patagonus is situated in the order Psittaciformes, encompassing all parrots and cockatoos, and the family Psittacidae, the true parrots of the New World and Old World tropics.[9] Within Psittacidae, it forms a distinct lineage among the long-tailed Neotropical parrots (tribe Arini), distinguished by molecular and morphological analyses that affirm its isolated generic status.[2] Four subspecies are currently recognized, varying primarily in plumage intensity and geographic isolation: C. p. patagonus (nominate, central Patagonia), C. p. andinus (Andean slopes), C. p. conlara (west-central Argentina), and C. p. bloxami (southern populations).[8]Phylogeny and Subspecies

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) occupies a monotypic genus within the Psittacidae family, subfamily Arinae, and tribe Arini, as established by molecular phylogenetic analyses of Neotropical parrots using mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences. These studies position it among core Arini taxa, with evolutionary affinities to other South American conure-like genera, reflecting a shared Neotropical radiation estimated to have occurred in the Miocene. Genus-level monotypy underscores its distinct morphological and behavioral adaptations, such as burrowing nest excavation, which differentiate it from congeners in related clades.[10] Population-level phylogeny, inferred from mitochondrial DNA (e.g., cytochrome b and control region), indicates an ancestral range in central Chile, with a single eastward dispersal across the Andes approximately 120,000 years ago during the Pleistocene, leading to divergence between western and eastern lineages. The Andean cordillera subsequently imposed a strong barrier to gene flow, fostering genetic structure and a stable hybrid zone in northern Patagonia where limited admixture occurs. This vicariant pattern aligns with phylogeographic patterns in other Andean avifauna, driven by Pleistocene climate oscillations rather than recent anthropogenic factors.[11][12] Four subspecies are currently recognized, primarily distinguished by geographic isolation, subtle size variations, and minor plumage differences, though taxonomic boundaries remain under scrutiny due to ongoing gene flow in contact zones:| Subspecies | Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| C. p. patagonus | Central to southeast Argentina | Nominate form; smaller size, olive-brown plumage with yellow lower back.[13][14] |

| C. p. andinus | Northwest Argentina | Adapted to Andean foothills; limited morphological data.[13][14] |

| C. p. conlara | West-central Argentina | Intermediate form in transitional habitats.[13][14] |

| C. p. bloxami | Central Chile | Largest subspecies; represents the ancestral western lineage.[13][14] |

Physical Characteristics

Morphology and Plumage

The Burrowing Parrot possesses a robust, stocky build typical of Arini parrots, with a strong, curved bill adapted for cracking hard seeds and excavating nesting burrows in cliffs.[2] Its wings are pointed and moderately long, facilitating agile flight in flocks, while the tail is long and graduated, aiding in maneuverability. Zygodactyl feet with sharp claws assist in climbing and digging.[15] Plumage is predominantly dull olive-green with gray-brown tones on the head, neck, back, breast, and mantle, providing camouflage in arid scrublands. Wing coverts exhibit a subtle glossy bronze sheen enhancing the olive coloration. A distinctive bare white patch adorns the cheeks, contrasting with the surrounding feathers, and the sides of the upper breast show creamy to buffy-white markings. Red feathers, particularly on the abdominal region and undertail coverts, are ornamental and produced by psittacofulvins, unique non-carotenoid pigments biosynthesized by parrots, signaling individual quality.[16][17][18] Sexual dichromatism is cryptic to the human eye but detectable via spectrometry; males display brighter reflectance in ultraviolet and visible spectra across several plumage patches, potentially aiding mate choice, while females appear duller overall.[19] Juveniles resemble adults but with softer, less defined plumage edges and reduced red pigmentation, undergoing a single annual prebasic molt. Bare parts include a pale gray to horn-colored bill, dark brown irises, and grayish legs.[16]Size, Weight, and Sexual Dimorphism

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) measures 39–52 cm in total length, including the tail, with wingspans of 23–25 cm.[20] [21] Body mass typically ranges from 240–310 g in adults, averaging around 270–280 g.[22] [23] Sexual dimorphism is slight, with no conspicuous differences in plumage coloration visible to the human eye, though spectrometric analysis reveals hidden dichromatism in feather reflectance between sexes.[24] [25] Males exhibit structural size advantages of approximately 5% over females, particularly in wing length and tarsus length, while bill length shows no significant difference.[26] [27] Body mass does not differ markedly between sexes after controlling for structural size.[28] This dimorphism aligns with patterns in other Arini parrots, where males are marginally larger, potentially linked to roles in territory defense and provisioning.[29]Distribution and Habitat

Geographic Range

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) is endemic to southern South America, with its primary distribution spanning central and southern Argentina from Salta and Córdoba provinces in the north to northeastern Santa Cruz province in the south, and extending westward into central Chile from the Atacama Region to the Maule Region.[1][30] Populations occur in dry, open habitats up to 2,000 meters elevation, though they are now patchily distributed due to historical declines.[1] The species comprises four subspecies with distinct ranges: C. p. andinus in northwestern Argentina (e.g., Salta, Jujuy, and Tucumán provinces); C. p. conlara in west-central Argentina (San Luis and Córdoba provinces); C. p. patagonus across central to southeastern Argentina from Mendoza and La Pampa southward to Chubut and Río Negro provinces, with post-breeding movements northward into northern Argentina and occasional vagrants to Uruguay; and C. p. byrsii in central Chile.[1][13] While once more continuous, current distributions reflect fragmentation from habitat loss and persecution, with core populations concentrated in arid steppes and river valleys.[30][1]Habitat Preferences and Adaptations

The Burrowing Parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) primarily inhabits arid and semi-arid open landscapes, including steppes, scrublands, and flat grasslands characterized by dry climates, strong winds, and low rainfall, ranging up to elevations of 2,000 m.[31] These preferences extend across southern Argentina and central Chile, where the species favors areas with accessible ravines or cliffs suitable for nesting, often along river valleys or in geomorphological features like alluvial terraces.[32] Substrates for nesting typically consist of sand mixed with small stones, which facilitate excavation while providing tunnel stability, with a preference for larger and taller ravines that support extensive colonies.[32] Nesting sites are selected at multiple scales, prioritizing intrinsic ravine features such as size, height, and south-facing orientation for microclimatic stability over broader landscape factors like distance to water, though proximity to water bodies correlates with higher nest densities.[32] This selection reflects adaptations to treeless environments, as the species is one of few parrots capable of primary cavity excavation, burrowing into soft cliffs to create nests that protect against predators and harsh weather.[32] Colony formation in expansive ravines leverages the dilution effect to minimize predation risk, enabling high-density breeding in otherwise resource-limited arid zones.[32] Physiologically, the Burrowing Parrot exhibits seasonal thermoregulatory adjustments suited to Patagonian extremes, including higher body mass in winter (mean 260.3 ± 6.3 g, 7.7% greater than summer) for insulation and broad thermoneutral zones year-round to conserve energy in unpredictable conditions.[33] Core body temperature remains stable across seasons with consistent circadian rhythms, while elevated mass-specific metabolic rates in summer support activity amid heat.[33] The species demonstrates behavioral flexibility by increasingly utilizing anthropogenic sites, such as urban quarries and rural cliffs in southwestern Buenos Aires province, adapting to habitat fragmentation.[3]Behavior and Ecology

Social Structure and Daily Activities

The burrowing parrot maintains a highly gregarious social structure, forming large flocks numbering in the hundreds to thousands of individuals year-round, except during incubation when pairs may isolate temporarily.[34][35] These flocks enhance predator detection through collective vigilance and enable coordinated movements for foraging and roosting, with birds exhibiting noisy vocalizations and synchronized flight patterns during group activities.[6] Pair bonds are typically long-term and monogamous, both socially and genetically, providing stability within the fluid flock dynamics.[4] Daily routines are diurnal, centered on foraging expeditions where flocks depart roosts at dawn to exploit ground-level resources such as seeds, fruits, and berries in open arid landscapes.[36] Foraging groups, documented up to 263 individuals in transit from breeding areas, display ground-feeding behaviors, often in agricultural fields or scrublands, with heightened sensitivity to environmental threats prompting sentinel-like scanning by peripheral members.[36][34] Midday may involve resting or preening in shaded areas, while late afternoon sees flocks returning noisily to communal roosts in cliff burrows, trees, or artificial structures like wires, where they aggregate for overnight protection.[6]Diet and Foraging Behavior

The diet of the burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) consists primarily of seeds foraged from the ground in open arid habitats, supplemented by fruits, berries, and pulp from plant pods, with vegetable matter occasionally consumed.[5] Fruits from woody species such as Prosopis alba, P. nigra, and Geoffroea decorticans become significant during the breeding season (September–February), comprising up to 74% of crop contents in January and supporting consistent breeding and molt due to their reliable availability compared to seasonal grass seeds.[37] Burrowing parrots predominate on soft seeds from unripe pods (wasting 4.1–11.1 viable seeds per pod) and exclusively consume the pulp encasing hard seeds from ripe pods of keystone Prosopis species, thereby facilitating seed dispersal through pod transport and discard. Foraging behavior involves dispersal in small flocks from nesting colonies to patches of natural or modified vegetation, where birds feed both on the ground and in low-standing plants; traveling flocks may reach 263 individuals, but feeding groups remain smaller and exhibit high vigilance, with sentinels alerting to threats during perching, feeding, or drinking.[39][34] In agricultural areas of northeastern Patagonia, they preferentially target post-harvest stover from wheat, maize, and sunflower fields (41% of observations), spilled grains on cultivated pastures (12%), and road margins (10%), largely ignoring growing crops and causing minimal damage (0.1–0.4% of sunflower yield, confined to field borders).[35] Individuals occasionally visit recently burned fields to ingest ground substances, potentially charcoal for digestive aid. Nestlings receive 3–6 feedings daily by adults provisioning from these sites.[39]Reproduction and Nesting

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) is a colonial nester, excavating burrows in soft sandstones, limestones, earthen cliffs, or ravines known as barrancas. Burrows typically measure an average depth of 1.5 meters and terminate in an incubation chamber where eggs are laid directly on bare ground without nesting material. Each burrow is occupied by a single breeding pair, and colonies can be extensive, with the largest known at El Cóndor in northeastern Patagonia, Argentina, supporting over 35,000 active nests, representing approximately 71% of the global breeding population. Pairs arrive at colonies 1-2 months prior to egg-laying and gradually depart post-fledging. Breeding occurs seasonally, with one clutch laid per year consisting of 2-5 eggs, and mean clutch sizes reported as 3.2 ± 1.3 eggs (range 1-5) in monitored nests. Incubation lasts approximately 24 days, primarily performed by the female during the day while the male incubates at night and provides food to the female. The species exhibits social and genetic monogamy in its breeding system. Hatching success can reach 81.3%, though nest success varies annually, with apparent success rates of 80.4% in some seasons and 51.2% in others due to factors like predation or abandonment. Chicks hatch and are fed by both parents, with fledging occurring after several weeks; detailed chick growth studies indicate variable productivity influenced by environmental conditions. Breeding pairs defend nests aggressively, showing risk-taking behaviors such as approaching threats closely. In recent years, populations have adapted to anthropogenic nesting sites, including urban structures, enabling breeding in modified habitats.[3][40][32][41][42][43][44]Physiological Adaptations

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) demonstrates robust thermoregulatory capabilities suited to the arid, seasonally variable climate of Patagonia, where temperatures can range from frosts and snow in winter to highs exceeding 30°C in summer. Individuals maintain a circadian rhythm in core body temperature, fluctuating between a minimum of 38.5°C before dawn and a maximum of 40.5°C in the afternoon, enabling precise daily adjustments to environmental demands.[45] This rhythm supports energy conservation during rest and activity peaks, reflecting physiological flexibility in endothermic regulation.[33] Seasonally, body mass increases significantly in winter compared to summer, providing enhanced insulation and fat reserves to withstand cold stress, with birds exhibiting broad thermoneutral zones that minimize metabolic costs across both seasons.[45] These adaptations, combined with behavioral nesting in burrows that buffer extreme temperatures, allow the species to inhabit elevations up to 2,000 m where heavy snow and frosts occur regularly.[33] Physiological stress responses, such as variations in leukocyte profiles during droughts, further indicate resilience to environmental extremes, though these are modulated by individual condition rather than fixed traits.[46] The parrot's strong mandibular musculature and bill morphology facilitate excavation of nesting cavities in soft cliffs, a primary cavity-excavating behavior unique among parrots, supported by efficient oxygen transport in blood parameters linked to foraging demands.[32] Hematological traits, including elevated heterophils during stress, correlate with body condition and support sustained burrowing efforts in nutrient-poor soils.[47] These features underscore causal links between physiology and ecology, enabling long-distance flights of up to 66 km at average speeds of 37 km/h for foraging in sparse habitats.[34]Conservation and Population Dynamics

Current Status and Population Estimates

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, indicating that it does not meet criteria for higher threat categories despite ongoing pressures.[1] This assessment reflects a large global population size exceeding thresholds for Vulnerable status (fewer than 10,000 mature individuals), but the species exhibits a decreasing trend due to habitat loss, illegal trapping, and agricultural conflicts.[1][7] Global population estimates place the number of mature individuals at approximately 95,000, derived from extrapolations of density data across core ranges in Argentina, Chile, and smaller populations in Bolivia.[1] Regional variations show concentrations in Patagonia, with Argentine subpopulations including around 8,000 pairs in southern areas and smaller groups elsewhere, while Chilean efforts have increased local numbers from 217 individuals in the 1980s to nearly 4,500 by 2021 through targeted conservation.[48][49] Local studies in urbanized Argentine sites report breeding pair estimates of 1,363–1,612, contributing to site-specific totals of about 5,448 individuals, though these represent subsets of the broader population.[50] Population declines are uneven, with heavier impacts in northern ranges from deforestation and persecution as crop pests, contrasted by stability or growth in protected Patagonian cliffs where nesting colonies persist.[1] Monitoring challenges, including variable survey methods and vast arid habitats, contribute to estimate uncertainties, but aerial and ground counts consistently support the overall large but declining status.[50][44]Major Threats

The burrowing parrot faces ongoing population declines primarily from habitat loss and degradation, driven by conversion of native grasslands and arid shrublands to intensive agriculture and overgrazing by livestock, which erodes soil stability in river valleys and cliffs critical for burrowing nests.[1][6] In Patagonia, Argentina, agricultural expansion has fragmented key breeding habitats, reducing available nesting sites and foraging areas for seeds and fruits.[51] Illegal capture for the international pet trade represents a severe historical and persistent threat, with 122,914 wild-caught individuals reported in trade since the species' listing on CITES Appendix II in 1981, despite regulatory efforts.[1] This exploitation targets adults and fledglings from large colonies, exacerbating declines in localized populations, particularly in northern Argentina and southern Chile.[7] Persecution as an agricultural pest contributes to direct mortality, as farmers destroy nests and shoot birds to protect crops like corn and sunflowers, with reports of colony raids in response to perceived damage.[51] In Argentina, where the species is nationally listed as threatened, such conflicts have led to the intentional sabotage of breeding cliffs.[3] Additional pressures include unregulated tourism in breeding areas, where off-road vehicles and foot traffic disturb colonies and cause chick mortality by collapsing burrows, as observed in coastal Patagonian sites.[6] Localized threats in Chile encompass invasive species predation, wildfires, and domestic pet attacks on nests, compounded by climate-driven changes in arid habitats.[49] Unusual mass die-offs, such as the 2021 event in Río Negro Province, Argentina, affecting thousands at colonies like El Cóndor, highlight vulnerabilities to unidentified factors including potential disease outbreaks or toxins, underscoring the need for monitoring.[52]Conservation Measures and Outcomes

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) benefits from international trade regulation under CITES Appendix II, listed in 1981, which has documented 122,914 wild-caught individuals exported since then, enabling monitored quotas to curb overexploitation for the pet trade.[1] In Chile, national protections enacted around 1986 prohibited hunting and trapping, coupled with enforcement and habitat safeguards along river basins, resulted in a population recovery for the subspecies C. p. bloxami from approximately 217 individuals in the mid-1980s to nearly 4,500 by 2021, though it remains classified as endangered domestically due to persistent vulnerabilities.[49] [3] In Argentina, where the species is categorized as threatened, measures include targeted colony protections by the Wildlife Conservation Society, such as advocating for legal safeguards of key nesting cliffs in Patagonia to mitigate agricultural habitat loss, alongside long-term monitoring programs funded by the World Parrot Trust since 2003 to assess distribution and ecological needs.[53] [51] Private initiatives, like those from Tompkins Conservation and Rewilding Argentina, focus on steppe restoration and anti-poaching in Patagonia, promoting indirect benefits through broader ecosystem recovery.[54] [55] Outcomes vary regionally: successful recoveries in Chile demonstrate the efficacy of strict enforcement against direct persecution, with breeding productivity observed in monitored urban-adjacent sites contributing to local stability.[49] In Argentina, adaptation to anthropogenic nesting substrates, such as quarries and urban cliffs, has buffered some populations against habitat degradation, yielding density estimates of up to 1.5 pairs per hectare in surveyed southwestern areas as of 2023, though overall declines persist in unprotected zones due to incomplete threat mitigation.[3] [50] Mass mortality events, such as those reported in 2021 from unknown causes, underscore gaps in comprehensive monitoring, with calls for expanded veterinary and genetic studies to enhance resilience.[52] Globally, the species' IUCN Least Concern status reflects these patchy successes, but subspecies-level threats highlight the need for sustained, cross-border efforts.Human Interactions

Aviculture and Captive Breeding

Burrowing parrots, commonly referred to as Patagonian conures in aviculture, have been maintained in captivity since the mid-20th century and were historically among the most frequently traded parrot species in Europe.[43] These birds exhibit hardiness in temperate climates, thriving in outdoor aviaries without the need for enclosed shelters once acclimatized, provided they are protected from extreme weather.[56] In pet settings, they demand substantial daily interaction due to their highly social disposition, forming strong pair bonds with mates or human caregivers, though their vocalizations can be intense and persistent.[57][22] Captive breeding of burrowing parrots typically occurs in spacious aviaries, where one or two pairs can successfully reproduce in enclosures as small as 4.5 meters long, though larger setups facilitate colonial nesting akin to their wild behavior.[22] Pairs generally reach sexual maturity around three years of age, though isolated reports indicate breeding as early as one year.[56] Monogamous bonding is common, necessitating careful pair selection to avoid aggression; breeding requires provision of deep nest boxes simulating natural burrows to encourage egg-laying, with clutches mirroring wild patterns of 2–5 eggs.[58] Successful reproduction demands meticulous attention to diet, enriched with proteins and calcium during egg production and chick-rearing phases, alongside monitoring for pair compatibility to minimize infanticide risks observed in some conure species.[59]Agricultural Conflicts and Pest Status

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) is frequently regarded by farmers in Argentina as an agricultural pest due to perceived crop raiding, particularly on seeds and grains in expanded cultivation areas of Patagonia.[6][60] This perception has led to official classification as a pest species, resulting in exclusion from national wildlife trade bans and ongoing persecution through shooting and habitat disturbance, especially in regions like Río Negro and Buenos Aires provinces where agricultural expansion overlaps with foraging ranges.[61][51] Empirical assessments, however, indicate minimal actual damage to crops. A 2016 study in northeastern Patagonia quantified foraging impacts across sunflower, corn, and alfalfa fields, recording negligible seed loss attributable to burrowing parrots—less than 0.1% of total yield in monitored plots—and concluded that no targeted pest management is warranted.[62] Observations confirmed that while flocks visit fields, their diet primarily consists of native seeds, fruits, and insects, with crop consumption opportunistic and not economically significant, challenging farmer claims of substantial losses in areas like Carmen de Patagones.[60][63] These discrepancies highlight broader human-wildlife conflicts driven by agricultural intensification into former grassland habitats, where anecdotal reports amplify perceived threats despite limited verifiable data.[64] Persecution persists, contributing to local population declines, though conservation advocates argue for evidence-based approaches over reactive culling, given the species' overall vulnerability from habitat loss and trapping.[65][56]Urban Adaptation and Anthropogenic Sites

The burrowing parrot (Cyanoliseus patagonus) exhibits notable flexibility in nesting habitat selection, enabling breeding populations to persist in urban and peri-urban landscapes through the exploitation of human-modified sites. These include abandoned quarries, roadside ravines, and water wells, which mimic the soft-soil cliffs preferred in natural settings but provide accessible cavities for burrowing.[66][3] Such adaptations have facilitated urban colonization, particularly in northern Argentinian Patagonia, where 57% of identified nesting sites and 60–80% of breeding pairs occur in urban environments, with the remainder in rural areas.[3] Nest density varies significantly across anthropogenic substrates, with mean densities highest in roadside ravines (exceeding those in quarries), and urban roadsides supporting greater concentrations than rural counterparts.[3] Colonies in these sites display facultative coloniality, ranging from solitary pairs to aggregations of up to 300 breeding pairs, allowing the species to maintain reproductive output amid habitat fragmentation.[67] In the southwest Buenos Aires province, urbanized habitats host substantial populations, with monitoring revealing stable breeding activity in modified ravines and cliffs proximate to human settlements.[50] This urban adaptation underscores the species' behavioral plasticity, as it shifts from pristine arid ecosystems to human-altered terrains without evident declines in site occupancy, though long-term viability depends on the persistence of these artificial substrates.[68] Observations confirm breeding success in such locales, contributing to broader patterns where over 40% of South American parrot species, including C. patagonus, reproduce within city limits.[69]References

- https://www.[mdpi](/page/MDPI).com/1424-2818/13/5/204