Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Limestone

View on Wikipedia

| Sedimentary rock | |

Limestone outcrop in the Torcal de Antequera nature reserve of Málaga, Spain | |

| Composition | |

|---|---|

| Calcium carbonate: inorganic crystalline calcite or organic calcareous material |

Limestone is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate CaCO3. Limestone forms when these minerals precipitate out of water containing dissolved calcium. This can take place through both biological and nonbiological processes, though biological processes, such as the accumulation of corals and shells in the sea, have likely been more important for the last 540 million years.[1][2] Limestone often contains fossils which provide scientists with information on ancient environments and on the evolution of life.[3]

About 20% to 25% of sedimentary rock is carbonate rock, and most of this is limestone.[4][3] The remaining carbonate rock is mostly dolomite, a closely related rock, which contains a high percentage of the mineral dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2. Magnesian limestone is an obsolete and poorly defined term used variously for dolomite, for limestone containing significant dolomite (dolomitic limestone), or for any other limestone containing a significant percentage of magnesium.[5] Most limestone was formed in shallow marine environments, such as continental shelves or platforms, though smaller amounts were formed in many other environments. Much dolomite is secondary dolomite, formed by chemical alteration of limestone.[6][7] Limestone is exposed over large regions of the Earth's surface, and because limestone is slightly soluble in rainwater, these exposures often are eroded to become karst landscapes. Most cave systems are found in limestone bedrock.

Limestone has numerous uses: as a chemical feedstock for the production of lime used for cement (an essential component of concrete), as aggregate for the base of roads, as white pigment or filler in products such as toothpaste or paint, as a soil conditioner, and as a popular decorative addition to rock gardens. Limestone formations contain about 30% of the world's petroleum reservoirs.[3]

Description

[edit]

Limestone is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Dolomite, CaMg(CO3)2, is an uncommon mineral in limestone, and siderite or other carbonate minerals are rare. However, the calcite in limestone often contains a few percent of magnesium. Calcite in limestone is divided into low-magnesium and high-magnesium calcite, with the dividing line placed at a composition of 4% magnesium. High-magnesium calcite retains the calcite mineral structure, which is distinct from dolomite. Aragonite does not usually contain significant magnesium.[8] Most limestone is otherwise chemically fairly pure, with clastic sediments (mainly fine-grained quartz and clay minerals) making up less than 5%[9] to 10%[10] of the composition. Organic matter typically makes up around 0.2% of a limestone and rarely exceeds 1%.[11]

Limestone often contains variable amounts of silica in the form of chert or siliceous skeletal fragments (such as sponge spicules, diatoms, or radiolarians).[12] Fossils are also common in limestone.[3]

Limestone is commonly white to gray in color. Limestone that is unusually rich in organic matter can be almost black in color, while traces of iron or manganese can give limestone an off-white to yellow to red color. The density of limestone depends on its porosity, which varies from 0.1% for the densest limestone to 40% for chalk. The density correspondingly ranges from 1.5 to 2.7 g/cm3. Although relatively soft, with a Mohs hardness of 2 to 4, dense limestone can have a crushing strength of up to 180 MPa.[13] For comparison, concrete typically has a crushing strength of about 40 MPa.[14]

Although limestones show little variability in mineral composition, they show great diversity in texture.[15] However, most limestone consists of sand-sized grains in a carbonate mud matrix. Because limestones are often of biological origin and are usually composed of sediment that is deposited close to where it formed, classification of limestone is usually based on its grain type and mud content.[9]

Grains

[edit]

Most grains in limestone are skeletal fragments of marine organisms such as coral or foraminifera.[16] These organisms secrete structures made of aragonite or calcite, and leave these structures behind when they die. Other carbonate grains composing limestones are ooids, peloids, and limeclasts (intraclasts and extraclasts).[17]

Skeletal grains have a composition reflecting the organisms that produced them and the environment in which they were produced.[18] Low-magnesium calcite skeletal grains are typical of articulate brachiopods, planktonic (free-floating) foraminifera, and coccoliths. High-magnesium calcite skeletal grains are typical of benthic (bottom-dwelling) foraminifera, echinoderms, and coralline algae. Aragonite skeletal grains are typical of molluscs, calcareous green algae, stromatoporoids, corals, and tube worms. The skeletal grains also reflect specific geological periods and environments. For example, coral grains are more common in high-energy environments (characterized by strong currents and turbulence) while bryozoan grains are more common in low-energy environments (characterized by quiet water).[19]

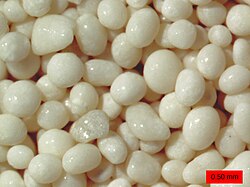

Ooids (sometimes called ooliths) are sand-sized grains (less than 2mm in diameter) consisting of one or more layers of calcite or aragonite around a central quartz grain or carbonate mineral fragment. These likely form by direct precipitation of calcium carbonate onto the ooid. Pisoliths are similar to ooids, but they are larger than 2 mm in diameter and tend to be more irregular in shape. Limestone composed mostly of ooids is called an oolite or sometimes an oolitic limestone. Ooids form in high-energy environments, such as the Bahama platform, and oolites typically show crossbedding and other features associated with deposition in strong currents.[20][21]

Oncoliths resemble ooids but show a radial rather than layered internal structure, indicating that they were formed by algae in a normal marine environment.[20]

Peloids are structureless grains of microcrystalline carbonate likely produced by a variety of processes.[22] Many are thought to be fecal pellets produced by marine organisms. Others may be produced by endolithic (boring) algae[23] or other microorganisms[24] or through breakdown of mollusc shells.[25] They are difficult to see in a limestone sample except in thin section and are less common in ancient limestones, possibly because compaction of carbonate sediments disrupts them.[23]

Limeclasts are fragments of existing limestone or partially lithified carbonate sediments. Intraclasts are limeclasts that originate close to where they are deposited in limestone, while extraclasts come from outside the depositional area. Intraclasts include grapestone, which is clusters of peloids cemented together by organic material or mineral cement. Extraclasts are uncommon, are usually accompanied by other clastic sediments, and indicate deposition in a tectonically active area or as part of a turbidity current.[26]

Mud

[edit]The grains of most limestones are embedded in a matrix of carbonate mud. This is typically the largest fraction of an ancient carbonate rock.[23] Mud consisting of individual crystals less than 5 μm (0.20 mils) in length is described as micrite.[27] In fresh carbonate mud, micrite is mostly small aragonite needles, which may precipitate directly from seawater,[28] be secreted by algae,[29] or be produced by abrasion of carbonate grains in a high-energy environment.[30] This is converted to calcite within a few million years of deposition. Further recrystallization of micrite produces microspar, with grains from 5 to 15 μm (0.20 to 0.59 mils) in diameter.[28]

Limestone often contains larger crystals of calcite, ranging in size from 0.02 to 0.1 mm (0.79 to 3.94 mils), that are described as sparry calcite or sparite. Sparite is distinguished from micrite by a grain size of over 20 μm (0.79 mils) and because sparite stands out under a hand lens or in thin section as white or transparent crystals. Sparite is distinguished from carbonate grains by its lack of internal structure and its characteristic crystal shapes.[31]

Geologists are careful to distinguish between sparite deposited as cement and sparite formed by recrystallization of micrite or carbonate grains. Sparite cement was likely deposited in pore space between grains, suggesting a high-energy depositional environment that removed carbonate mud. Recrystallized sparite is not diagnostic of depositional environment.[31]

Other characteristics

[edit]

Limestone outcrops are recognized in the field by their softness (calcite and aragonite both have a Mohs hardness of less than 4, well below common silicate minerals) and because limestone bubbles vigorously when a drop of dilute hydrochloric acid is dropped on it. Dolomite is also soft but reacts only feebly with dilute hydrochloric acid, and it usually weathers to a characteristic dull yellow-brown color due to the presence of ferrous iron. This is released and oxidized as the dolomite weathers.[9] Impurities (such as clay, sand, organic remains, iron oxide, and other materials) will cause limestones to exhibit different colors, especially with weathered surfaces.

The makeup of a carbonate rock outcrop can be estimated in the field by etching the surface with dilute hydrochloric acid. This etches away the calcite and aragonite, leaving behind any silica or dolomite grains. The latter can be identified by their rhombohedral shape.[9]

Crystals of calcite, quartz, dolomite or barite may line small cavities (vugs) in the rock. Vugs are a form of secondary porosity, formed in existing limestone by a change in environment that increases the solubility of calcite.[32]

Dense, massive limestone is sometimes described as "marble". For example, the famous Portoro "marble" of Italy is actually a dense black limestone.[33] True marble is produced by recrystallization of limestone during regional metamorphism that accompanies the mountain building process (orogeny). It is distinguished from dense limestone by its coarse crystalline texture and the formation of distinctive minerals from the silica and clay present in the original limestone.[34]

Classification

[edit]

Two major classification schemes, the Folk and Dunham, are used for identifying the types of carbonate rocks collectively known as limestone.

Folk classification

[edit]Robert L. Folk developed a classification system that places primary emphasis on the detailed composition of grains and interstitial material in carbonate rocks.[35] Based on composition, there are three main components: allochems (grains), matrix (mostly micrite), and cement (sparite). The Folk system uses two-part names; the first refers to the grains and the second to the cement. For example, a limestone consisting mainly of ooids, with a crystalline matrix, would be termed an oosparite. It is helpful to have a petrographic microscope when using the Folk scheme, because it is easier to determine the components present in each sample.[36]

Dunham classification

[edit]Robert J. Dunham published his system for limestone in 1962. It focuses on the depositional fabric of carbonate rocks. Dunham divides the rocks into four main groups based on relative proportions of coarser clastic particles, based on criteria such as whether the grains were originally in mutual contact, and therefore self-supporting, or whether the rock is characterized by the presence of frame builders and algal mats. Unlike the Folk scheme, Dunham deals with the original porosity of the rock. The Dunham scheme is more useful for hand samples because it is based on texture, not the grains in the sample.[37]

A revised classification was proposed by Wright (1992). It adds some diagenetic patterns to the classification scheme.[38]

Other descriptive terms

[edit]

Travertine is a term applied to calcium carbonate deposits formed in freshwater environments, particularly waterfalls, cascades and hot springs. Such deposits are typically massive, dense, and banded. When the deposits are highly porous, so that they have a spongelike texture, they are typically described as tufa. Secondary calcite deposited by supersaturated meteoric waters (groundwater) in caves is also sometimes described as travertine. This produces speleothems, such as stalagmites and stalactites.[39]

Coquina is a poorly consolidated limestone composed of abraded pieces of coral, shells, or other fossil debris. When better consolidated, it is described as coquinite.[40]

Chalk is a soft, earthy, fine-textured limestone composed of the tests of planktonic microorganisms such as foraminifera, while marl is an earthy mixture of carbonates and silicate sediments.[40]

Formation

[edit]Limestone forms when calcite or aragonite precipitate out of water containing dissolved calcium, which can take place through both biological and nonbiological processes.[41] The solubility of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) is controlled largely by the amount of dissolved carbon dioxide (CO2) in the water. This is summarized in the reaction:

- CaCO3 + H2O + CO2 → Ca2+ + 2 HCO−3

Increases in temperature or decreases in pressure tend to reduce the amount of dissolved CO2 and precipitate CaCO3. Reduction in salinity also reduces the solubility of CaCO3, by several orders of magnitude for fresh water versus seawater.[42]

Near-surface water of the earth's oceans are oversaturated with CaCO3 by a factor of more than six.[43] The failure of CaCO3 to rapidly precipitate out of these waters is likely due to interference by dissolved magnesium ions with nucleation of calcite crystals, the necessary first step in precipitation. Precipitation of aragonite may be suppressed by the presence of naturally occurring organic phosphates in the water. Although ooids likely form through purely inorganic processes, the bulk of CaCO3 precipitation in the oceans is the result of biological activity.[44] Much of this takes place on carbonate platforms.

The origin of carbonate mud,[30] and the processes by which it is converted to micrite,[45] continue to be a subject of research. Modern carbonate mud is composed mostly of aragonite needles around 5 μm (0.20 mils) in length. Needles of this shape and composition are produced by calcareous algae such as Penicillus, making this a plausible source of mud.[46] Another possibility is direct precipitation from the water. A phenomenon known as whitings occurs in shallow waters, in which white streaks containing dispersed micrite appear on the surface of the water. It is uncertain whether this is freshly precipitated aragonite or simply material stirred up from the bottom, but there is some evidence that whitings are caused by biological precipitation of aragonite as part of a bloom of cyanobacteria or microalgae.[47] However, stable isotope ratios in modern carbonate mud appear to be inconsistent with either of these mechanisms, and abrasion of carbonate grains in high-energy environments has been put forward as a third possibility.[30]

Formation of limestone has likely been dominated by biological processes throughout the Phanerozoic, the last 540 million years of the Earth's history. Limestone may have been deposited by microorganisms in the Precambrian, prior to 540 million years ago, but inorganic processes were probably more important and likely took place in an ocean more highly oversaturated in calcium carbonate than the modern ocean.[48]

Diagenesis

[edit]Diagenesis is the process in which sediments are compacted and turned into solid rock. During diagenesis of carbonate sediments, significant chemical and textural changes take place. For example, aragonite is converted to low-magnesium calcite. Diagenesis is the likely origin of pisoliths, concentrically layered particles ranging from 1 to 10 mm (0.039 to 0.394 inches) in diameter found in some limestones. Pisoliths superficially resemble ooids but have no nucleus of foreign matter, fit together tightly, and show other signs that they formed after the original deposition of the sediments.[49]

Silicification occurs early in diagenesis, at low pH and temperature, and contributes to fossil preservation.[50] Silicification takes place through the reaction:[50]

- CaCO3 + H2O + CO2 + H4SiO4 → SiO2 + Ca2+ + 2 HCO−3 + 2 H2O

Fossils are often preserved in exquisite detail as chert.[50][51]

Cementing takes place rapidly in carbonate sediments, typically within less than a million years of deposition. Some cementing occurs while the sediments are still under water, forming hardgrounds. Cementing accelerates after the retreat of the sea from the depositional environment, as rainwater infiltrates the sediment beds, often within just a few thousand years. As rainwater mixes with groundwater, aragonite and high-magnesium calcite are converted to low-calcium calcite. Cementing of thick carbonate deposits by rainwater may commence even before the retreat of the sea, as rainwater can infiltrate over 100 km (60 miles) into sediments beneath the continental shelf.[52]

As carbonate sediments are increasingly deeply buried under younger sediments, chemical and mechanical compaction of the sediments increases. Chemical compaction takes place by pressure solution of the sediments. This process dissolves minerals from points of contact between grains and redeposits it in pore space, reducing the porosity of the limestone from an initial high value of 40% to 80% to less than 10%.[53] Pressure solution produces distinctive stylolites, irregular surfaces within the limestone at which silica-rich sediments accumulate. These may reflect dissolution and loss of a considerable fraction of the limestone bed. At depths greater than 1 km (0.62 miles), burial cementation completes the lithification process. Burial cementation does not produce stylolites.[54]

When overlying beds are eroded, bringing limestone closer to the surface, the final stage of diagenesis takes place. This produces secondary porosity as some of the cement is dissolved by rainwater infiltrating the beds. This may include the formation of vugs, which are crystal-lined cavities within the limestone.[54]

Diagenesis may include conversion of limestone to dolomite by magnesium-rich fluids. There is considerable evidence of replacement of limestone by dolomite, including sharp replacement boundaries that cut across bedding.[55] The process of dolomitization remains an area of active research,[56] but possible mechanisms include exposure to concentrated brines in hot environments (evaporative reflux) or exposure to diluted seawater in delta or estuary environments (Dorag dolomitization).[57] However, Dorag dolomitization has fallen into disfavor as a mechanism for dolomitization,[58] with one 2004 review paper describing it bluntly as "a myth".[56] Ordinary seawater is capable of converting calcite to dolomite, if the seawater is regularly flushed through the rock, as by the ebb and flow of tides (tidal pumping).[55] Once dolomitization begins, it proceeds rapidly, so that there is very little carbonate rock containing mixed calcite and dolomite. Carbonate rock tends to be either almost all calcite/aragonite or almost all dolomite.[57]

Occurrence

[edit]About 20% to 25% of sedimentary rock is carbonate rock,[3] and most of this is limestone.[17][3] Limestone is found in sedimentary sequences as old as 2.7 billion years.[59] However, the compositions of carbonate rocks show an uneven distribution in time in the geologic record. About 95% of modern carbonates are composed of high-magnesium calcite and aragonite.[60] The aragonite needles in carbonate mud are converted to low-magnesium calcite within a few million years, as this is the most stable form of calcium carbonate.[28] Ancient carbonate formations of the Precambrian and Paleozoic contain abundant dolomite, but limestone dominates the carbonate beds of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. Modern dolomite is quite rare. There is evidence that, while the modern ocean favors precipitation of aragonite, the oceans of the Paleozoic and middle to late Cenozoic favored precipitation of calcite. This may indicate a lower Mg/Ca ratio in the ocean water of those times.[61] This magnesium depletion may be a consequence of more rapid sea floor spreading, which removes magnesium from ocean water. The modern ocean and the ocean of the Mesozoic have been described as "aragonite seas".[62]

Most limestone was formed in shallow marine environments, such as continental shelves or platforms. Such environments form only about 5% of the ocean basins, but limestone is rarely preserved in continental slope and deep sea environments. The best environments for deposition are warm waters, which have both a high organic productivity and increased saturation of calcium carbonate due to lower concentrations of dissolved carbon dioxide. Modern limestone deposits are almost always in areas with very little silica-rich sedimentation, reflected in the relative purity of most limestones. Reef organisms are destroyed by muddy, brackish river water, and carbonate grains are ground down by much harder silicate grains.[63] Unlike clastic sedimentary rock, limestone is produced almost entirely from sediments originating at or near the place of deposition.[64]

Limestone formations tend to show abrupt changes in thickness. Large moundlike features in a limestone formation are interpreted as ancient reefs, which when they appear in the geologic record are called bioherms. Many are rich in fossils, but most lack any connected organic framework like that seen in modern reefs. The fossil remains are present as separate fragments embedded in ample mud matrix. Much of the sedimentation shows indications of occurring in the intertidal or supratidal zones, suggesting sediments rapidly fill available accommodation space in the shelf or platform.[65] Deposition is also favored on the seaward margin of shelves and platforms, where there is upwelling deep ocean water rich in nutrients that increase organic productivity. Reefs are common here, but when lacking, ooid shoals are found instead. Finer sediments are deposited close to shore.[66]

The lack of deep sea limestones is due in part to rapid subduction of oceanic crust, but is more a result of dissolution of calcium carbonate at depth. The solubility of calcium carbonate increases with pressure and even more with higher concentrations of carbon dioxide, which is produced by decaying organic matter settling into the deep ocean that is not removed by photosynthesis in the dark depths. As a result, there is a fairly sharp transition from water saturated with calcium carbonate to water unsaturated with calcium carbonate, the lysocline, which occurs at the calcite compensation depth of 4,000 to 7,000 m (13,000 to 23,000 feet). Below this depth, foraminifera tests and other skeletal particles rapidly dissolve, and the sediments of the ocean floor abruptly transition from carbonate ooze rich in foraminifera and coccolith remains (Globigerina ooze) to silicic mud lacking carbonates.[67]

In rare cases, turbidites or other silica-rich sediments bury and preserve benthic (deep ocean) carbonate deposits. Ancient benthic limestones are microcrystalline and are identified by their tectonic setting. Fossils typically are foraminifera and coccoliths. No pre-Jurassic benthic limestones are known, probably because carbonate-shelled plankton had not yet evolved.[68]

Limestones also form in freshwater environments.[69] These limestones are not unlike marine limestone, but have a lower diversity of organisms and a greater fraction of silica and clay minerals characteristic of marls. The Green River Formation is an example of a prominent freshwater sedimentary formation containing numerous limestone beds.[70] Freshwater limestone is typically micritic. Fossils of charophyte (stonewort), a form of freshwater green algae, are characteristic of these environments, where the charophytes produce and trap carbonates.[71]

Limestones may also form in evaporite depositional environments.[72][73] Calcite is one of the first minerals to precipitate in marine evaporites.[74]

Limestone and living organisms

[edit]

Most limestone is formed by the activities of living organisms near reefs, but the organisms responsible for reef formation have changed over geologic time. For example, stromatolites are mound-shaped structures in ancient limestones, interpreted as colonies of cyanobacteria that accumulated carbonate sediments, but stromatolites are rare in younger limestones.[75] Organisms precipitate limestone both directly as part of their skeletons, and indirectly by removing carbon dioxide from the water by photosynthesis and thereby decreasing the solubility of calcium carbonate.[71]

Limestone shows the same range of sedimentary structures found in other sedimentary rocks. However, finer structures, such as lamination, are often destroyed by the burrowing activities of organisms (bioturbation). Fine lamination is characteristic of limestone formed in playa lakes, which lack the burrowing organisms.[76] Limestones also show distinctive features such as geopetal structures, which form when curved shells settle to the bottom with the concave face downwards. This traps a void space that can later be filled by sparite. Geologists use geopetal structures to determine which direction was up at the time of deposition, which is not always obvious with highly deformed limestone formations.[77]

The cyanobacterium Hyella balani can bore through limestone; as can the green alga Eugamantia sacculata and the fungus Ostracolaba implexa.[78]

Micritic mud mounds

[edit]Micricitic mud mounds are subcircular domes of micritic calcite that lacks internal structure. Modern examples are up to several hundred meters thick and a kilometer across, and have steep slopes (with slope angles of around 50 degrees). They may be composed of peloids swept together by currents and stabilized by Thalassia grass or mangroves. Bryozoa may also contribute to mound formation by helping to trap sediments.[79]

Mud mounds are found throughout the geologic record, and prior to the early Ordovician, they were the dominant reef type in both deep and shallow water. These mud mounds likely are microbial in origin. Following the appearance of frame-building reef organisms, mud mounds were restricted mainly to deeper water.[80]

Organic reefs

[edit]Organic reefs form at low latitudes in shallow water, not more than a few meters deep. They are complex, diverse structures found throughout the fossil record. The frame-building organisms responsible for organic reef formation are characteristic of different geologic time periods: Archaeocyathids appeared in the early Cambrian; these gave way to sponges by the late Cambrian; later successions included stromatoporoids, corals, algae, bryozoa, and rudists (a form of bivalve mollusc).[81][82][83] The extent of organic reefs has varied over geologic time, and they were likely most extensive in the middle Devonian, when they covered an area estimated at 5,000,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi). This is roughly ten times the extent of modern reefs. The Devonian reefs were constructed largely by stromatoporoids and tabulate corals, which were devastated by the late Devonian extinction.[84]

Organic reefs typically have a complex internal structure. Whole body fossils are usually abundant, but ooids and interclasts are rare within the reef. The core of a reef is typically massive and unbedded, and is surrounded by a talus that is greater in volume than the core. The talus contains abundant intraclasts and is usually either floatstone, with 10% or more of grains over 2mm in size embedded in abundant matrix, or rudstone, which is mostly large grains with sparse matrix. The talus grades to planktonic fine-grained carbonate mud, then noncarbonate mud away from the reef.[81]

Limestone landscape

[edit]

Limestone is partially soluble, especially in acid, and therefore forms many erosional landforms. These include limestone pavements, pot holes, cenotes, caves and gorges. Such erosion landscapes are known as karsts. Limestone is less resistant to erosion than most igneous rocks, but more resistant than most other sedimentary rocks. It is therefore usually associated with hills and downland, and occurs in regions with other sedimentary rocks, typically clays.[85][86]

Karst regions overlying limestone bedrock tend to have fewer visible above-ground sources (ponds and streams), as surface water easily drains downward through joints in the limestone. While draining, water and organic acid from the soil slowly (over thousands or millions of years) enlarges these cracks, dissolving the calcium carbonate and carrying it away in solution. Most cave systems are through limestone bedrock. Cooling groundwater or mixing of different groundwaters will also create conditions suitable for cave formation.[85]

Coastal limestones are often eroded by organisms which bore into the rock by various means. This process is known as bioerosion. It is most common in the tropics, and it is known throughout the fossil record.[87]

Bands of limestone emerge from the Earth's surface in often spectacular rocky outcrops and islands. Examples include the Rock of Gibraltar,[88] the Burren in County Clare, Ireland;[89] Malham Cove in North Yorkshire and the Isle of Wight,[90] England; the Great Orme in Wales;[91] on Fårö near the Swedish island of Gotland,[92] the Niagara Escarpment in Canada/United States;[93] Notch Peak in Utah;[94] the Ha Long Bay National Park in Vietnam;[95] and the hills around the Lijiang River and Guilin city in China.[96]

The Florida Keys, islands off the south coast of Florida, are composed mainly of oolitic limestone (the Lower Keys) and the carbonate skeletons of coral reefs (the Upper Keys), which thrived in the area during interglacial periods when sea level was higher than at present.[97]

Unique habitats are found on alvars, extremely level expanses of limestone with thin soil mantles. The largest such expanse in Europe is the Stora Alvaret on the island of Öland, Sweden.[98] Another area with large quantities of limestone is the island of Gotland, Sweden.[99] Huge quarries in northwestern Europe, such as those of Mount Saint Peter (Belgium/Netherlands), extend for more than a hundred kilometers.[100]

Uses

[edit]

Limestone is a raw material that is used globally in a variety of different ways including construction, agriculture and as industrial materials.[102] Limestone is very common in architecture, especially in Europe and North America. Many landmarks across the world, including the Great Pyramid and its associated complex in Giza, Egypt, were made of limestone. So many buildings in Kingston, Ontario, Canada were, and continue to be, constructed from it that it is nicknamed the 'Limestone City'.[103] Limestone, metamorphosed by heat and pressure produces marble, which has been used for many statues, buildings and stone tabletops.[104] On the island of Malta, a variety of limestone called Globigerina limestone was, for a long time, the only building material available, and is still very frequently used on all types of buildings and sculptures.[105]

Limestone can be processed into many various forms such as brick, cement, powdered/crushed, or as a filler.[102] Limestone is readily available and relatively easy to cut into blocks or more elaborate carving.[101] Ancient American sculptors valued limestone because it was easy to work and good for fine detail. Going back to the Late Preclassic period (by 200–100 BCE), the Maya civilization (Ancient Mexico) created refined sculpture using limestone because of these excellent carving properties. The Maya would decorate the ceilings of their sacred buildings (known as lintels) and cover the walls with carved limestone panels. Carved on these sculptures were political and social stories, and this helped communicate messages of the king to his people.[106] Limestone is long-lasting and stands up well to exposure, which explains why many limestone ruins survive. However, it is very heavy (density 2.6[107]), making it impractical for tall buildings, and relatively expensive as a building material.

Limestone was most popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Railway stations, banks and other structures from that era were made of limestone in some areas. It is used as a façade on some skyscrapers, but only in thin plates for covering, rather than solid blocks. In the United States, Indiana, most notably the Bloomington area, has long been a source of high-quality quarried limestone, called Indiana limestone. Many famous buildings in London are built from Portland limestone. Houses built in Odesa in Ukraine in the 19th century were mostly constructed from limestone and the extensive remains of the mines now form the Odesa Catacombs.[108]

Limestone was also a very popular building block in the Middle Ages in the areas where it occurred, since it is hard, durable, and commonly occurs in easily accessible surface exposures. Many medieval churches and castles in Europe are made of limestone. Beer stone was a popular kind of limestone for medieval buildings in southern England.[109]

-

Limestone quarry at Cedar Creek, Virginia, US

-

Limestone as building material

-

Limestone is used worldwide as building material.

Limestone is the raw material for production of lime, primarily known for treating soils, purifying water and smelting copper. Lime is an important ingredient used in chemical industries.[110] Limestone and (to a lesser extent) marble are reactive to acid solutions, making acid rain a significant problem to the preservation of artifacts made from this stone. Many limestone statues and building surfaces have suffered severe damage due to acid rain.[111][112] Likewise limestone gravel has been used to protect lakes vulnerable to acid rain, acting as a pH buffering agent.[113] Acid-based cleaning chemicals can also etch limestone, which should only be cleaned with a neutral or mild alkali-based cleaner.[114]

Other uses include:

- It is the raw material for the manufacture of quicklime (calcium oxide), slaked lime (calcium hydroxide), cement and mortar.[59]

- Pulverized limestone is used as a soil conditioner to neutralize acidic soils (agricultural lime).[115]

- Is crushed for use as aggregate—the solid base for many roads as well as in asphalt concrete.[59]

- As a reagent in flue-gas desulfurization, where it reacts with sulfur dioxide for air pollution control.[116]

- In glass making, particularly in the manufacture of soda–lime glass.[117]

- As an additive toothpaste, paper, plastics, paint, tiles, and other materials as both white pigment and a cheap filler.[118]

- As rock dust, to suppress methane explosions in underground coal mines.[119]

- Purified, it is added to bread and cereals as a source of calcium.[120]

- As a calcium supplement in livestock feed, such as for poultry (when ground up).[121]

- For remineralizing and increasing the alkalinity of purified water to prevent pipe corrosion and to restore essential nutrient levels.[122]

- In blast furnaces, limestone binds with silica and other impurities to remove them from the iron.[123]

- It can aid in the removal of toxic components created from coal burning plants and layers of polluted molten metals.[110]

Many limestone formations are porous and permeable, which makes them important petroleum reservoirs.[124] About 20% of North American hydrocarbon reserves are found in carbonate rock. Carbonate reservoirs are very common in the petroleum-rich Middle East,[59] and carbonate reservoirs hold about a third of all petroleum reserves worldwide.[125] Limestone formations are also common sources of metal ores, because their porosity and permeability, together with their chemical activity, promotes ore deposition in the limestone. The lead-zinc deposits of Missouri and the Northwest Territories are examples of ore deposits hosted in limestone.[59]

Scarcity

[edit]Limestone is a major industrial raw material that is in constant demand. This raw material has been essential in the iron and steel industry since the nineteenth century.[126] Companies have never had a shortage of limestone; however, it has become a concern as the demand continues to increase[127] and it remains in high demand today.[128] The major potential threats to supply in the nineteenth century were regional availability and accessibility.[126] The two main accessibility issues were transportation and property rights. Other problems were high capital costs on plants and facilities due to environmental regulations and the requirement of zoning and mining permits.[104] These two dominant factors led to the adaptation and selection of other materials that were created and formed to design alternatives for limestone that suited economic demands.[126]

Limestone was classified as a critical raw material, and with the potential risk of shortages, it drove industries to find new alternative materials and technological systems. This allowed limestone to no longer be classified as critical as replacement substances increased in production; minette ore is a common substitute, for example.[126]

Occupational safety and health

[edit]| NFPA 704 safety square | |

|---|---|

Limestone |

Powdered limestone as a food additive is generally recognized as safe[130] and limestone is not regarded as a hazardous material. However, limestone dust can be a mild respiratory and skin irritant, and dust that gets into the eyes can cause corneal abrasions. Because limestone contains small amounts of silica, inhalation of limestone dust could potentially lead to silicosis or cancer.[129]

United States

[edit]The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for limestone exposure in the workplace as 15 mg/m3 (0.0066 gr/cu ft) total exposure and 5 mg/m3 (0.0022 gr/cu ft) respiratory exposure over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 10 mg/m3 (0.0044 gr/cu ft) total exposure and 5 mg/m3 (0.0022 gr/cu ft) respiratory exposure over an 8-hour workday.[131]

Graffiti

[edit]Removing graffiti from weathered limestone is difficult because it is a porous and permeable material. The surface is fragile, therefore usual abrasion methods run the risk of severe surface loss. Since it is an acid-sensitive stone, some cleaning agents cannot be used due to adverse effects.[132]

Gallery

[edit]-

A stratigraphic section of Ordovician limestone exposed in central Tennessee, U.S. The less-resistant and thinner beds are composed of shale. The vertical lines are drill holes for explosives used during road construction.

-

Photo and etched section of a sample of fossiliferous limestone from the Kope Formation (Upper Ordovician) near Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S.

-

biosparite limestone of the Brassfield Formation (Lower Silurian) near Fairborn, Ohio, U.S., showing grains mainly composed of crinoid fragments

-

Fossils in limestone from the northern Black Sea region

See also

[edit]- Coral sand – Carbonate sand formed in warm oceans

- Charmant Som

- In Praise of Limestone – Poem by W. H. Auden

- Kurkar – Regional name for an aeolian quartz calcrete on the Levantine coast

- Limepit – Old method of calcining limestone

- Sandstone – Type of sedimentary rock

- Liming (soil) – Application of minerals to soil

References

[edit]- ^ Boggs, Sam (2006). Principles of sedimentology and stratigraphy (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 177, 181. ISBN 0-13-154728-3.

- ^ Leong, Goh Cheng (27 October 1995). Certificate Physics And Human Geography; Indian Edition. Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-19-562816-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Boggs 2006, p. 159.

- ^ Blatt, Harvey; Tracy, Robert J. (1996). Petrology : igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic (2nd ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. 295–300. ISBN 0-7167-2438-3.

- ^ Jackson, Julia A., ed. (1997). "Magnesian limestone". Glossary of geology (Fourth ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: American Geological Institute. ISBN 0-922152-34-9.

- ^ Blatt, Harvey; Middleton, Gerard; Murray, Raymond (1980). Origin of sedimentary rocks (2d ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. pp. 446, 510–531. ISBN 0-13-642710-3.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 182–194.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 448–449.

- ^ a b c d Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 295.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 467.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Oates, Tony (17 September 2010). "Lime and Limestone". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology: 1–53. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1209130507212019.a01.pub3. ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6.

- ^ "Compressive strength test". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 452.

- ^ a b Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 295–300.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 449.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 161–164.

- ^ a b Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 297–299.

- ^ Boggs 2006, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Adachi, Natsuko; Ezaki, Yoichi; Liu, Jianbo (February 2004). "The fabrics and origins of peloids immediately after the end-Permian extinction, Guizhou Province, South China". Sedimentary Geology. 164 (1–2): 161–178. Bibcode:2004SedG..164..161A. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2003.10.007.

- ^ a b c Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 298.

- ^ Chafetz, Henry S. (1986). "Marine Peloids: A Product of Bacterially Induced Precipitation of Calcite". SEPM Journal of Sedimentary Research. 56 (6): 812–817. doi:10.1306/212F8A58-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D.

- ^ Samankassou, Elias; Tresch, Jonas; Strasser, André (26 November 2005). "Origin of peloids in Early Cretaceous deposits, Dorset, South England" (PDF). Facies. 51 (1–4): 264–274. Bibcode:2005Faci...51..264S. doi:10.1007/s10347-005-0002-8. S2CID 128851366.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 299–300, 304.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 460.

- ^ a b c Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 300.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Trower, Elizabeth J.; Lamb, Michael P.; Fischer, Woodward W. (16 March 2019). "The Origin of Carbonate Mud". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (5): 2696–2703. Bibcode:2019GeoRL..46.2696T. doi:10.1029/2018GL081620. S2CID 134970335.

- ^ a b Boggs 2006, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 315–317.

- ^ Fratini, Fabio; Pecchioni, Elena; Cantisani, Emma; Antonelli, Fabrizio; Giamello, Marco; Lezzerini, Marco; Canova, Roberta (December 2015). "Portoro, the black and gold Italian "marble"". Rendiconti Lincei. 26 (4): 415–423. doi:10.1007/s12210-015-0420-7. S2CID 129625906.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 474.

- ^ "Carbonate Classification: SEPM STRATA".

- ^ Folk, R. L. (1974). Petrology of Sedimentary Rocks. Austin, Texas: Hemphill Publishing. ISBN 0-914696-14-9.

- ^ Dunham, R. J. (1962). "Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional textures". In Ham, W. E. (ed.). Classification of Carbonate Rocks. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Memoirs. Vol. 1. pp. 108–121.

- ^ Wright, V.P. (1992). "A revised Classification of Limestones". Sedimentary Geology. 76 (3–4): 177–185. Bibcode:1992SedG...76..177W. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(92)90082-3.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 479–480.

- ^ a b Boggs 2006, p. 172.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Boggs 2006, pp. 174–176.

- ^ Morse, John W.; Mackenzie, F. T. (1990). Geochemistry of sedimentary carbonates. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 217. ISBN 0-08-086962-9.

- ^ Boggs 2006, pp. 176–182.

- ^ Jerry Lucia, F. (September 2017). "Observations on the origin of micrite crystals". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 86: 823–833. Bibcode:2017MarPG..86..823J. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2017.06.039.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 460–464.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 180.

- ^ Boggs 2006, pp. 177, 181.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 497–501.

- ^ a b c Götz, Annette E.; Montenari, Michael; Costin, Gelu (2017). "Silicification and organic matter preservation in the Anisian Muschelkalk: Implications for the basin dynamics of the central European Muschelkalk Sea". Central European Geology. 60 (1): 35–52. Bibcode:2017CEJGl..60...35G. doi:10.1556/24.60.2017.002. ISSN 1788-2281.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 497–503.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 312.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 507–509.

- ^ a b Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 312–316.

- ^ a b Boggs 2006, pp. 186–187.

- ^ a b Machel, Hans G. (2004). "Concepts and models of dolomitization: a critical reappraisal". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 235 (1): 7–63. Bibcode:2004GSLSP.235....7M. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2004.235.01.02. S2CID 131159219.

- ^ a b Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 512–528.

- ^ Luczaj, John A. (November 2006). "Evidence against the Dorag (mixing-zone) model for dolomitization along the Wisconsin arch ― A case for hydrothermal diagenesis". AAPG Bulletin. 90 (11): 1719–1738. Bibcode:2006BAAPG..90.1719L. doi:10.1306/01130605077.

- ^ a b c d e Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 445.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 448.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 159-161.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 176-177.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 446, 733.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 468-470.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 446-447.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 306-307.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 474-479.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 308-309.

- ^ Roeser, Patricia; Franz, Sven O.; Litt, Thomas (1 December 2016). "Aragonite and calcite preservation in sediments from Lake Iznik related to bottom lake oxygenation and water column depth". Sedimentology. 63 (7): 2253–2277. Bibcode:2016Sedim..63.2253R. doi:10.1111/sed.12306. ISSN 1365-3091. S2CID 133211098.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, p. 480-482.

- ^ a b Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 309-310.

- ^ Trewin, N. H.; Davidson, R. G. (1999). "Lake-level changes, sedimentation and faunas in a Middle Devonian basin-margin fish bed". Journal of the Geological Society. 156 (3): 535–548. Bibcode:1999JGSoc.156..535T. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.156.3.0535. S2CID 131241083.

- ^ "Term 'evaporite'". Oilfield Glossary. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. 662.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 446, 471–474.

- ^ Blatt, Middleton & Murray 1980, pp. 446–471.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 304.

- ^ Ehrlich, Henry Lutz; Newman, Dianne K. (2009). Geomicrobiology (5th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-8493-7907-9. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- ^ Blatt & Tracy 1996, p. 307.

- ^ Pratt, Brian R. (1995). "The origin, biota, and evolution of deep-water mud-mounds". Spec. Publs Int. Ass. Sediment. 23: 49–123. ISBN 1-4443-0412-7. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ a b Blatt & Tracy 1996, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Riding, Robert (July 2002). "Structure and composition of organic reefs and carbonate mud mounds: concepts and categories". Earth-Science Reviews. 58 (1–2): 163–231. Bibcode:2002ESRv...58..163R. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(01)00089-7.

- ^ Wood, Rachel (1999). Reef evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-857784-2. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ McGhee, George R. (2013). When the invasion of land failed : the legacy of the Devonian extinctions. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-231-16057-5.

- ^ a b Thornbury, William D. (1969). Principles of geomorphology (2d ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 303–344. ISBN 0-471-86197-9.

- ^ "Karst Landscapes of Illinois: Dissolving Bedrock and Collapsing Soil". Prairie Research Institute. Illinois State Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Taylor, P. D.; Wilson, M. A. (2003). "Palaeoecology and evolution of marine hard substrate communities" (PDF). Earth-Science Reviews. 62 (1–2): 1–103. Bibcode:2003ESRv...62....1T. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00131-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009.

- ^ Rodrı́guez-Vidal, J.; Cáceres, L.M.; Finlayson, J.C.; Gracia, F.J.; Martı́nez-Aguirre, A. (October 2004). "Neotectonics and shoreline history of the Rock of Gibraltar, southern Iberia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 23 (18–19). Elsevier (2004): 2017–2029. Bibcode:2004QSRv...23.2017R. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.02.008. hdl:11441/137125. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ McNamara, M.; Hennessy, R. (2010). "The geology of the Burren region, Co. Clare, Ireland" (PDF). Project NEEDN, The Burren Connect Project. Ennistymon: Clare County Council. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Isle of Wight, Minerals" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2006.

- ^ Juerges, A.; Hollis, C. E.; Marshall, J.; Crowley, S. (May 2016). "The control of basin evolution on patterns of sedimentation and diagenesis: an example from the Mississippian Great Orme, North Wales". Journal of the Geological Society. 173 (3): 438–456. Bibcode:2016JGSoc.173..438J. doi:10.1144/jgs2014-149.

- ^ Cruslock, Eva M.; Naylor, Larissa A.; Foote, Yolanda L.; Swantesson, Jan O.H. (January 2010). "Geomorphologic equifinality: A comparison between shore platforms in Höga Kusten and Fårö, Sweden and the Vale of Glamorgan, South Wales, UK". Geomorphology. 114 (1–2): 78–88. Bibcode:2010Geomo.114...78C. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.02.019.

- ^ Luczaj, John A. (2013). "Geology of the Niagara Escarpment in Wisconsin". Geoscience Wisconsin. 22 (1): 34. doi:10.54915/jeoi3571. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Miller, James F. (1969). "Conodont Fauna of the Notch Peak Limestone (Cambro-Ordovician), House Range, Utah". Journal of Paleontology. 43 (2): 413–439. JSTOR 1302317.

- ^ Tran Duc Thanh; Waltham Tony (1 September 2001). "The outstanding value of the geology of Ha Long Bay". Advances in Natural Sciences. 2 (3). ISSN 0866-708X.

- ^ Waltham, Tony (2010). Migon, Piotr (ed.). Guangxi Karst: The Fenglin and Fengcong Karst of Guilin and Yangshuo, in Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. Springer. pp. 293–302. ISBN 978-90-481-3054-2.

- ^ Mitchell-Tapping, Hugh J. (Spring 1980). "Depositional History of the Oolite of the Miami Limestone Formation". Florida Scientist. 43 (2): 116–125. JSTOR 24319647.

- ^ Thorsten Jansson, Stora Alvaret, Lenanders Tryckeri, Kalmar, 1999

- ^ Laufeld, S. (1974). Silurian Chitinozoa from Gotland. Fossils and Strata. Universitetsforlaget.

- ^ Pereira, Dolores; Tourneur, Francis; Bernáldez, Lorenzo; Blázquez, Ana García (2014). "Petit Granit: A Belgian limestone used in heritage, construction and sculpture" (PDF). Episodes. 38 (2): 30. Bibcode:2014EGUGA..16...30P. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b Cassar, Joann (2010). "The use of limestone in historic context". In Smith, Bernard J. (ed.). Limestone in the Built Environment: Present-day Challenges for the Preservation of the Past. Geographical Society of London. pp. 13–23. ISBN 978-1-86239-294-6. Retrieved 20 December 2024.

- ^ a b Oates, J. A. H. (11 July 2008). "7.2 Market Overview". Lime and Limestone: Chemistry and Technology, Production and Uses. John Wiley & Sons. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-527-61201-7.

- ^ "Welcome to the Limestone City". Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- ^ a b Corathers, L.A. (15 February 2019). "Lime". Metals and minerals: US Geological Survey Minerals Yearbook 2014, Volume 1. Washington, DC: USGS (published 2018). p. 43.1. ISBN 978-1-4113-4253-8.

- ^ Cassar, Joann (2010). "The use of limestone in a historic context – the experience of Malta". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 331 (1): 13–25. Bibcode:2010GSLSP.331...13C. doi:10.1144/SP331.2. S2CID 129082854.

- ^ Schele, Linda; Miller, Mary Ellen. The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Kimbell Art Museum. p. 41.

- ^ P. V. Sharma (1997), Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, Cambridge University Press, p. 17, doi:10.1017/CBO9781139171168, ISBN 1-139-17116-X

- ^ "Odessa catacombs". Odessa travel guide. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Ashurst, John; Dimes, Francis G. (1998). Conservation of building and decorative stone. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 117. ISBN 0-7506-3898-2.

- ^ a b Bliss, J. D., Hayes, T. S., & Orris, G. J. (2012, August). Limestone—A Crucial and Versatile Industrial Mineral Commodity. Retrieved February 23, 2021, from https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3089/fs2008-3089.pdf

- ^ Reisener, A.; Stäckle, B.; Snethlage, R. (1995). "ICP on effects on materials". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 85 (4): 2701–2706. Bibcode:1995WASP...85.2701R. doi:10.1007/BF01186242. S2CID 94721996.

- ^ "Approaches in modeling the impact of air pollution-induced material degradation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ Clayton, Janet L.; Dannaway, Eric S.; Menendez, Raymond; Rauch, Henry W.; Renton, John J.; Sherlock, Sean M.; Zurbuch, Peter E. (1998). "Application of Limestone to Restore Fish Communities in Acidified Streams". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 18 (2): 347–360. Bibcode:1998NAJFM..18..347C. doi:10.1577/1548-8675(1998)018<0347:AOLTRF>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Hatch, Jonathan (18 April 2018). "How to clean limestone". How to Clean Things. Saint Paul Media, Inc. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ Oates, J. A. H. (11 July 2008). Lime and Limestone: Chemistry and Technology, Production and Uses. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 111–3. ISBN 978-3-527-61201-7.

- ^ Gutiérrez Ortiz, F. J.; Vidal, F.; Ollero, P.; Salvador, L.; Cortés, V.; Giménez, A. (February 2006). "Pilot-Plant Technical Assessment of Wet Flue Gas Desulfurization Using Limestone". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 45 (4): 1466–1477. doi:10.1021/ie051316o.

- ^ Kogel, Jessica Elzea (2006). Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses. SME. ISBN 0-87335-233-5. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017.

- ^ Huwald, Eberhard (2001). "Calcium carbonate - pigment and filler". In Tegethoff, F. W. (ed.). Calcium Carbonate. Basel: Birkhäuser. pp. 160–170. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-8245-3_7. ISBN 3-0348-9490-2.

- ^ Man, C.K.; Teacoach, K.A. (2009). "How does limestone rock dust prevent coal dust explosions in coal mines?" (PDF). Mining Engineering: 61. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Why Fortified Flour?". Wessex Mill. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "A Guide to Giving Your Layer Hens Enough Calcium". Poultry One. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009.

- ^ "Nutrient minerals in drinking-water and the potential health consequences of consumption of demineralized and remineralized and altered mineral content drinking-water: Consensus of the meeting". World Health Organization report. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007.

- ^ Tylecote, R. F. (1992). A history of metallurgy (2nd ed.). London: Institute of Materials. ISBN 0-901462-88-8.

- ^ Archie, G.E. (1952). "Classification of Carbonate Reservoir Rocks and Petrophysical Considerations". AAPG Bulletin. 36. doi:10.1306/3D9343F7-16B1-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- ^ Boggs 2006, p. p=159.

- ^ a b c d Haumann, S. (2020). "Critical and scarce: the remarkable career of limestone 1850–1914". European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire. 27 (3): 273–293. doi:10.1080/13507486.2020.1737651. S2CID 221052279.

- ^ Sparenberg, O.; Heymann, M. (2020). "Introduction: resource challenges and constructions of scarcity in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries". European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire. 27 (3): 243–252. doi:10.1080/13507486.2020.1737653. S2CID 221055042.

- ^ ResearchAndMarkets.com (9 June 2020). "Global Limestone Market Analysis and Forecasts 2020-2027 - Steady Growth Projected over the Next Few Years - ResearchAndMarkets.com". Limestone - Global Market Trajectory & Analytics. businesswire.com. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ a b Lhoist North America. "Material Safety Data Sheet: Limestone" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21". US Food & Drug Administration. US Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ "Limestone". NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. CDC. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Weaver, Martin E. (October 1995). "Removing Graffiti from Historic Masonry". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Boynton, Robert S. (1980). Chemistry and Technology of Lime and Limestone. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-02771-5.