Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cardiac plexus

View on Wikipedia| Cardiac plexus | |

|---|---|

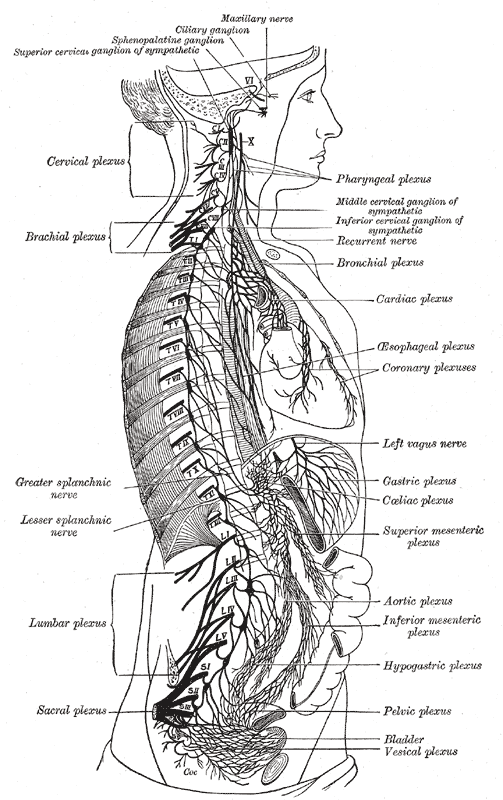

The right sympathetic chain and its connections with the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic plexuses. (Cardiac plexus labeled at center right.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | plexus cardiacus |

| TA98 | A14.3.03.013 |

| TA2 | 6688 |

| FMA | 6628 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The cardiac plexus is a plexus of nerves situated at the base of the heart that innervates the heart.

Structure

[edit]The cardiac plexus is divided into a superficial part, which lies in the concavity of the aortic arch, and a deep part, between the aortic arch and the trachea. The two parts are, however, closely connected. The sympathetic component of the cardiac plexus comes from cardiac nerves, which originate from the sympathetic trunk. The parasympathetic component of the cardiac plexus originates from the cardiac branches of the vagus nerve.

Superficial part

[edit]The superficial part of the cardiac plexus lies beneath the aortic arch, in front of the right pulmonary artery. It is formed by the superior cervical cardiac branch of the left sympathetic trunk and the inferior cardiac branch of the left vagus nerve.[1] A small ganglion, the cardiac ganglion of Wrisberg, is occasionally found connected with these nerves at their point of junction. This ganglion, when present, is situated immediately beneath the arch of the aorta, on the right side of the ligamentum arteriosum.

The superficial part of the cardiac plexus gives branches to:

- the deep part of the plexus.

- the anterior coronary plexus.

- the left anterior pulmonary plexus.

Deep part

[edit]The deep part of the cardiac plexus is situated in front of the bifurcation of the trachea (known as the carina), above the point of division of the pulmonary artery, and behind the aortic arch. It is formed by the cardiac nerves derived from the cervical ganglia of the sympathetic trunk, and the cardiac branches of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves.

The only cardiac nerves which do not enter into the formation of the deep part of the cardiac plexus are the superior cardiac nerve of the left sympathetic trunk, and the lower of the two superior cervical cardiac branches from the left vagus nerve, which pass to the superficial part of the plexus.

Right half

[edit]The branches from the right half of the deep part of the cardiac plexus pass, some in front of, and others behind, the right pulmonary artery; the former, the more numerous, transmit a few filaments to the anterior pulmonary plexus, and are then continued onward to form part of the anterior coronary plexus; those behind the pulmonary artery distribute a few filaments to the right atrium, and are then continued onward to form part of the posterior coronary plexus.

Left half

[edit]The left half of the deep part of the plexus is connected with the superficial part of the cardiac plexus, and gives filaments to the left atrium, and to the anterior pulmonary plexus, and is then continued to form the greater part of the posterior coronary plexus.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 984 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 984 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Gibbins, Ian (2012-01-01), Mai, Jürgen K.; Paxinos, George (eds.), "Chapter 5 - Peripheral Autonomic Pathways", The Human Nervous System (Third Edition), San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 141–185, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-374236-0.10005-7, ISBN 978-0-12-374236-0, retrieved 2020-11-20

External links

[edit]- thoraxlesson4 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (thoraxautonomicner)

- thoraxlesson5 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

Cardiac plexus

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Location and gross organization

The cardiac plexus is a network of autonomic nerve fibers situated at the base of the heart, primarily surrounding the aortic arch and the tracheal bifurcation. This plexus serves as a key site for the convergence of sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs that regulate cardiac function. It lies within the superior mediastinum, positioned close to the origins of the great vessels emerging from the heart.[3][4] The gross organization of the cardiac plexus features a flattened, irregular meshwork of interconnected nerve fibers and small ganglia, blending sympathetic and parasympathetic components into a unified structure. It is broadly divided into superficial and deep parts relative to the aortic arch: the superficial portion lies anterior to the arch, nestled between the arch and the right pulmonary artery, while the deep portion is positioned posterior to the arch and anterior to the tracheal bifurcation. These divisions facilitate the distribution of fibers toward the heart's coronary arteries and conduction system. The plexus maintains continuity with adjacent pulmonary and coronary plexuses, allowing for coordinated visceral innervation.[3] In terms of anatomical relations, the superficial cardiac plexus is situated anterior to the right pulmonary artery and inferior to the ligamentum arteriosum, while the deep part rests posterior to the ascending aorta and pulmonary trunk, anterior to the trachea and tracheal bifurcation. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve, looping around the aortic arch, contributes branches to the deep plexus and lies in close proximity along the tracheoesophageal groove. These relations position the plexus amid critical thoracic structures, influencing surgical approaches in the mediastinum.[3][4][7] Embryologically, the cardiac plexus arises from neural crest cells that migrate during early heart development to establish visceral efferent pathways. These cells, originating from the vagal and cardiac neural crest regions, contribute significantly to the formation of parasympathetic ganglia and fibers within the plexus, particularly at the venous pole of the heart. This migration occurs during early embryonic stages, around E8-E10 in mouse embryos, integrating with placodal-derived elements to form the mixed autonomic innervation.[8][9]Superficial part

The superficial part of the cardiac plexus is formed primarily by the superior cervical cardiac branch from the left sympathetic trunk, which carries postganglionic sympathetic fibers, and the superior cardiac branch from the left vagus nerve, which conveys preganglionic parasympathetic fibers.[1] These contributions converge to create a network anterior to the right pulmonary artery and to the right of the ligamentum arteriosum, beneath the aortic arch.[2] Within this region, the vagus branches interconnect with the sympathetic fibers, forming a dense plexus that includes the cardiac ganglion of Wrisberg as a key junction point; from here, mixed nerve bundles distribute primarily to the atria.[1] Ascending branches from the superficial plexus extend toward the superior aspect of the heart, providing innervation mainly to the sinoatrial node and the atrial myocardium to modulate heart rate and atrial contractility.[10] Microscopically, the superficial cardiac plexus consists predominantly of preganglionic parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerves, intermixed with postganglionic sympathetic fibers from the cervical ganglia, reflecting its role in integrating autonomic inputs before final synaptic relays in atrial ganglia.[11] This composition supports rapid parasympathetic modulation while facilitating sympathetic enhancement of cardiac output.Deep part

The deep part of the cardiac plexus is formed by interlacing branches from the superior, middle, and inferior cervical cardiac nerves, which convey sympathetic postganglionic fibers, and from the recurrent laryngeal nerves, which provide parasympathetic preganglionic fibers.[12][13] This posterior division receives contributions predominantly from the right superior, middle, and inferior cervical cardiac nerves, as well as the left middle and inferior cervical cardiac nerves, alongside bilateral recurrent laryngeal inputs.[14][12] Positioned between the aortic arch and the tracheal bifurcation, the deep part lies posterior to the pulmonary trunk bifurcation, anterior to the trachea, and communicates with the anterior superficial part across vascular structures.[15][16] A notable feature in its distribution is the left inferior cervical cardiac branch, which courses posteriorly and loops around the ligamentum arteriosum, the remnant of the fetal ductus arteriosus, before joining the plexus. Within the deep part, these nerves form a dense interconnecting network that extends branches along the coronary arteries toward the ventricular myocardium and the atrioventricular node, facilitating targeted autonomic modulation.[15][13] The fiber composition features a higher proportion of sympathetic postganglionic fibers directed to the ventricles and Purkinje fibers, supporting enhanced myocardial contractility and conduction.[17][18]Neural contributions

Sympathetic inputs

The sympathetic inputs to the cardiac plexus primarily originate from postganglionic neurons located in the superior, middle, and inferior (including the fused stellate) cervical ganglia of the sympathetic chain. Preganglionic sympathetic fibers arise from intermediolateral cell column neurons in the upper thoracic spinal segments T1 through T4, with occasional contributions from T5. These preganglionic fibers exit the spinal cord via ventral roots, pass through the white rami communicantes to enter the sympathetic trunk, and ascend to synapse in the cervical paravertebral ganglia.[10][19][1] The postganglionic fibers from these cervical ganglia form the cervical cardiac nerves, which initially course superiorly alongside the common carotid arteries before descending along the arch of the aorta to converge on the cardiac plexus near the aortic arch and pulmonary trunk. The right sympathetic trunk provides a greater proportion of fibers to the right cardiac plexus and right heart structures, while the left sympathetic trunk contributes more extensively to the left side, reflecting the bilateral but asymmetric organization of the innervation. These pathways ensure targeted distribution, with fibers integrating into both the superficial and deep portions of the cardiac plexus.[10][1][3] Upon reaching the cardiac plexus, the sympathetic cardiac branches pass through the plexus to distribute fibers to the heart, releasing norepinephrine to influence cardiac excitability. This integration allows for the convergence of sympathetic signals with local neural networks, facilitating coordinated modulation of heart rate and contractility. Notably, asymmetry persists in these inputs: right-sided cervical cardiac nerves predominate in accelerating the sinoatrial node, whereas left-sided nerves exert stronger effects on ventricular force generation.[1][20][19]Parasympathetic inputs

The parasympathetic innervation of the cardiac plexus originates from the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X), with preganglionic fibers arising primarily from the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus in the medulla oblongata.[10][21] These fibers travel via the vagus nerve, exiting the skull through the jugular foramen and descending in the carotid sheath before branching to the heart.[22] The pathways involve superior and inferior cervical cardiac branches from both the right and left vagus nerves, which contribute to the cardiac plexus; additionally, the left vagus provides input through its recurrent laryngeal nerve via inferior cardiac branches.[10][23] These branches often form common trunks with sympathetic fibers, more frequently on the right side (approximately 67% in fetuses) than the left (20% in fetuses), before integrating into the plexus.[23] The preganglionic fibers are long, synapsing with postganglionic neurons in terminal ganglia located within or near the cardiac plexus and on the heart surface.[21][11] Within the cardiac plexus, parasympathetic fibers integrate into both the superficial and deep parts, where postganglionic neurons release acetylcholine onto muscarinic receptors in cardiac tissue.[10] This neurotransmission slows sinoatrial node firing and reduces atrioventricular conduction velocity, contributing to overall cardiac inhibition.[21] Parasympathetic fibers are concentrated in the atrial regions, with sparser distribution to the ventricles.[24] There is notable asymmetry in vagal inputs: the right vagus primarily influences sinoatrial node inhibition, while the left vagus exerts greater control over atrioventricular node delay, though some overlap exists.[10][25]Function

Role in cardiac regulation

The cardiac plexus plays a central role in autonomic regulation of the heart by integrating sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs to modulate cardiac output and rhythm. Sympathetic activation through the plexus enhances heart rate (positive chronotropy), atrioventricular conduction velocity (positive dromotropy), and myocardial contractility (positive inotropy), primarily via stimulation of β1-adrenergic receptors on cardiac myocytes and pacemaker cells.[26] This augmentation supports increased cardiac performance during physiological demands such as exercise or stress. In contrast, parasympathetic activation via the plexus decreases heart rate (negative chronotropy) and slows atrioventricular nodal conduction (negative dromotropy) through muscarinic M2 receptor activation, establishing vagal tone dominance under resting conditions to conserve energy.[26] The dual innervation mediated by the cardiac plexus enables fine-tuned adjustments to cardiac function through integrative mechanisms, such as baroreceptor reflexes, where afferent signals from arterial baroreceptors modulate efferent sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow via the plexus to maintain blood pressure homeostasis and optimize cardiac output.[26] For instance, elevated blood pressure triggers increased parasympathetic activity and reduced sympathetic tone through the plexus, thereby lowering heart rate and contractility. This balanced control allows rapid responses to stressors, ensuring adaptive cardiovascular performance.[27] The plexuses distribute fibers to the sinoatrial node, atrioventricular node, atria, and ventricles, ensuring coordinated electromechanical activity across cardiac chambers.[25] Neurotransmitter dynamics within the cardiac plexus underpin these regulatory effects, with norepinephrine released from sympathetic postganglionic fibers binding to adrenergic receptors to drive excitatory responses, and acetylcholine from parasympathetic fibers activating muscarinic receptors for inhibitory actions.[26] Additionally, neuropeptides such as vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), co-released from parasympathetic neurons, contribute to coronary vasodilation and mild positive inotropic effects, enhancing myocardial perfusion during autonomic activation.[28]Interactions with other plexuses

The cardiac plexus maintains intricate connections with the pulmonary plexus, primarily through shared vagal branches that facilitate coordinated reflexes between the heart and lungs during respiration. The deep portion of the cardiac plexus, located anterior to the tracheal bifurcation, directly links to the anterior pulmonary plexus, allowing parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve to distribute to both structures.[1] This integration enables cardiopulmonary receptors to detect changes in intrathoracic pressure and blood flow, triggering vagal afferents that converge in the nucleus tractus solitarius for reflex adjustments in heart rate and pulmonary vascular tone.[1] The cardiac plexus integrates with the phrenic nerve through minor sensory afferents, primarily via sympathetic communications that contribute to pain referral pathways in cardiac pathology. The phrenic nerve, originating from C3-C5 roots, exchanges fibers with the cardiac plexus via the ansa subclavia and inferior cervical cardiac nerves, including catecholaminergic elements that may serve sensory functions.[29] These connections allow cardiac nociceptive signals to travel along phrenic pathways, potentially referring pain to the shoulder or neck during ischemic events, though the contribution remains limited compared to primary sympathetic routes.[29] Bidirectional signaling within the cardiac plexus involves receiving sensory inputs from coronary afferents, which are relayed to the spinal cord primarily via sympathetic chains for central processing. Coronary afferents, including both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers, detect mechanical and chemical changes in the myocardium and vasculature, conveying information on ischemia or distension back through the plexus.[11] Sympathetic afferents reenter the upper thoracic spinal cord (T1-T5 levels) via the sympathetic trunk and dorsal root ganglia, enabling reflexes that modulate autonomic outflow to the heart.[11] Functional synergy between the cardiac plexus and the carotid sinus plexus enhances baroreflex arcs, optimizing blood pressure homeostasis through complementary autonomic modulation. Baroreceptors in the carotid sinus detect arterial pressure changes and signal via the glossopharyngeal nerve to the nucleus tractus solitarius, which inhibits sympathetic outflow and activates vagal efferents to the cardiac plexus.[30] This interaction allows the cardiac plexus to adjust sinoatrial node firing and ventricular contractility in concert with vascular tone alterations, forming a negative feedback loop that stabilizes systemic pressure during fluctuations.[30]Clinical significance

Associated disorders

Cardiac autonomic neuropathy (CAN) represents a primary pathological condition affecting the cardiac plexus, often resulting from diabetic or other damage to autonomic nerve fibers. In diabetic CAN, progressive degeneration of small nerve fibers in the cardiac plexus leads to impaired parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation, manifesting as reduced heart rate variability (HRV) and an increased risk of arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia, due to unbalanced autonomic control.[31] Primary autonomic neuropathies, including non-diabetic forms, can involve damage to the intrinsic cardiac ganglia and neurons, contributing to silent ischemia and sudden cardiac death through diminished reflex responses to hemodynamic changes.[24] Surgical trauma to the autonomic nerves supplying the heart frequently occurs during procedures like coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), causing temporary denervation that disrupts normal sympathetic-parasympathetic balance. This denervation can result in sinus bradycardia attributable to unopposed parasympathetic activity or orthostatic hypotension from impaired baroreflex-mediated vasoconstriction, typically resolving within weeks to months as nerve function recovers.[32] Inflammatory conditions, such as viral myocarditis, can involve the cardiac autonomic nerves through direct neuronal inflammation or secondary fibrosis, altering nerve conduction and autonomic signaling. In viral myocarditis, immune-mediated damage to nerve fibers exacerbates arrhythmias and heart failure by promoting sympathetic hyperactivity and vagal withdrawal.[33] Congenital anomalies rarely affect the cardiac plexus directly, but autonomic innervation impairment has been observed in DiGeorge syndrome (22q11.2 deletion), where developmental defects in neural crest-derived structures lead to vasomotor instability and autonomic imbalance that heightens risks of hypotension and arrhythmias post-stress or surgery.[34] Diagnostic markers for cardiac plexus impairment include abnormal heart rate responses during tilt-table testing, where failure to appropriately modulate heart rate and blood pressure upon postural change indicates underlying autonomic dysfunction, often confirming plexus-related issues in suspected CAN or post-surgical cases.[24]Surgical and diagnostic relevance

In surgical procedures involving the thorax, the cardiac plexus must be carefully considered to avoid unintended disruption, which can lead to cardiac denervation and subsequent arrhythmias. During heart transplantation, the extrinsic cardiac nerves forming the plexus are severed, resulting in complete autonomic denervation of the donor heart immediately post-procedure, potentially contributing to early postoperative arrhythmias due to loss of sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation.[35] Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy, often performed for hyperhidrosis or refractory ventricular arrhythmias, risks partial or complete disruption of the sympathetic contributions to the cardiac plexus by interrupting the thoracic sympathetic chain at levels T1-T4, which may exacerbate arrhythmogenic risks if the procedure extends beyond targeted segments.[36] Diagnostic imaging plays a key role in identifying abnormalities affecting the cardiac plexus, particularly in cases of neurogenic tumors. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can visualize enlargement or mass effects from tumors such as schwannomas originating from the cardiac plexus or adjacent vagus nerve branches, appearing as well-defined, enhancing soft-tissue masses in the mediastinum or pericardium that may compress cardiac structures.[37] Positron emission tomography (PET) scans using metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) assess autonomic nervous system activity by evaluating uptake in sympathetic nerve terminals within the cardiac plexus and intrinsic ganglia, with reduced uptake indicating denervation or dysfunction in conditions like heart failure or post-surgical states.[38] Electrophysiological assessments provide non-invasive evaluation of cardiac plexus function following surgical interventions. Holter monitoring detects signs of denervation, such as reduced heart rate variability or fixed sinus rates, in the early postoperative period after procedures like sympathectomy or transplantation, helping to quantify the extent of autonomic imbalance.[39] Spectral analysis of heart rate variability (HRV) from Holter data further evaluates plexus integrity by measuring low-frequency (sympathetic) and high-frequency (parasympathetic) components, where diminished variability post-surgery signals impaired autonomic regulation.[40] Therapeutic interventions targeting the cardiac plexus inputs have shown promise in managing heart failure. Implantable vagal nerve stimulation devices, such as those applied at the cervical level, enhance parasympathetic tone to the cardiac plexus, improving left ventricular function and reducing remodeling in patients with reduced ejection fraction, as evidenced by clinical trials demonstrating decreased hospitalization rates.[41] The cardiac plexus was first systematically described by Wilhelm His in 1884, with modern anatomical mapping advanced through intraoperative nerve stimulation techniques that identify functional neural pathways during cardiac surgery to guide precise interventions.[42][43]References

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/[neuroscience](/page/Neuroscience)/cardiac-plexus

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1923077-overview