Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

China Development Bank

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Simplified Chinese | 国家开发银行 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 國家開發銀行 | ||||||

| |||||||

China Development Bank (CDB) is a policy bank of China under the State Council. Established in 1994, it has been described as the engine that powers the national government's economic development policies.[2][3] It has raised funds for numerous large-scale infrastructure projects, including the Three Gorges Dam and the Shanghai Pudong International Airport.

The bank is the second-largest bond issuer in China after the Ministry of Finance. In 2009, it accounted for about a quarter of the country's yuan bonds and is the biggest foreign-currency lender. CDB debt is owned by local banks and treated as a risk-free asset under the proposed People's Republic of China capital adequacy rules (i.e. the same treatment as PRC government bonds).[3]

History

[edit]

The China Development Bank (CDB) was established in 1994 to provide development-oriented financing for high-priority government projects, particularly major infrastructure and projects that raise quality of life.[4]: 209 It is under the direct jurisdiction of the State Council and the People's Central Government. At present, it has 35 branches across the country and one representative office.

The main objective as a state financial institution is to support the macroeconomic policies of the central government and to support national economic development and strategic structural changes in the economy.[5] The bank provides financing for national projects such as infrastructure development, basic industries, energy, and transportation.[6] Most of CDB's loans are for domestic projects, and it began lending for projects abroad in the early 2000s.[7]: 41

From 1994 to 1998, CDB's fundraising was subject to a higher degree of state control than in later periods.[7]: 32 In the 1990s, CDB facilitated the creation of China's interbank bond market.[7]: 9 Initially, the People's Bank of China (PBOC) required domestic financial institutions such as commercial banks to buy policy bank bonds.[7]: 32 At this stage, the PBOC usually set high yields and did not permit the apportioned bonds to be sold on the secondary market.[7]: 33 In February 1996, CDB began its first overseas bond issuance in Japan, followed a year later by an issuance in the United States.[7]: 34 Overseas issuance helped CDB diversify its funding sources.[7]: 34 Ultimately, the issuance of bonds allowed CDB to become a financially independent bank without the state's tax revenues.[7]: 9

In April 1998, former PBOC deputy governor Chen Yuan, the eldest son of Chen Yun, was appointed CDB's governor.[7]: 34 [8]: 63 Chen implemented reforms designed to increase CDB's autonomy by reducing state involvement in CDB's fundraising and lending.[7]: 34

From 1998 to 2008, CDB increased its fundraising autonomy and used an auction-based bond issuance mechanism to raise its funds.[7]: 32 In 1999, CDB offered China's first floating rate bond.[7]: 35

CDB plays a major role in alleviating infrastructure and energy bottlenecks in the Chinese economy. In 2003, CDB made loan arrangements for, or evaluated and underwrote, a total of 460 national debt projects and issued 246.8 billion yuan in loans. This accounted for 41% of its total investment. CDB's loans to the "bottleneck" investments that the government prioritizes amounted to 91% of its total loan count. It also issued a total of 357.5 billion yuan in loans to western areas and more than 174.2 billion yuan to old industrial bases in Northeast China. These loans substantially increased the economic growth and structural readjustments of the Chinese economy.[9]

In 2005 and 2006, CDB successfully issued two pilot Asset-Backed Securities[10] (ABS) products in the domestic China market. Along with other ABS products issued by China Construction Bank, CDB has created a foundation for a promising debt capital and structured finance market.[11][12]

China and Venezuela established the China-Venezuela Joint Fund in 2007, with the goal of offering capital funding for infrastructure projects in Venezuela which can be performed by Chinese companies.[7]: 98–99 CDB lent $4 billion to the fund and the Venezuelan Economic and Social Development Bank (BANDES) contributed $2 billion.[7]: 98

As part of China's response to the 2008 financial crisis, emphasis on CDB's policy aspects increased and the state formalized its credit guarantee for CDB.[7]: 32 CDB was one of the financial agencies implementing China's stimulus plan and vastly increased its lending for infrastructure and industrial projects.[7]: 37–38

From 2009 to 2019, CDB has issued 1.6 trillion yuan in loans to more than 4,000 projects involving infrastructure, communications, transportation, and basic industries. The investments are spread along the Yellow River, and both south and north of the Yangtze River. CDB has been increasingly focusing on developing the western and northwestern provinces in China. This could help reduce the growing economic disparity in the western provinces, and it has the potential to revitalize the old industrial bases of northeast China.[13]

In 2010, CDB provided $30 billion in financing to Chinese solar power manufacturers.[14]: 1

At the end of 2010, CDB held US$687.8 billion in loans, more than twice the amount of the World Bank.[3]

After Chen left the governorship of CDB in 2013, the bank's institutional power decreased.[7]: 157

The next CDB governor, Hu Huaibang, removed CDB personnel to staff the bank with personnel loyal to himself.[7]: 158 Hu then leveraged his personal influence to approve large amounts of industrial loans which ultimately failed.[7]: 158 Hu was removed from office in 2018 on suspicion of corruption and he was sentenced to life in prison in 2021 for accepting bribes to approve projects that should not have passed CDB criteria.[7]: 158–159 Following these events, CDB became significantly more cautious in its financing decisions.[7]: 159

CDB is among the state entities which contribute to the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, which was established in an effort to decrease China's reliance on foreign semiconductor companies.[15]: 274 The fund was established in 2014.[15]: 274

In 2014, CDB was one of the funders of the Silk Road Fund, along with the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, China Investment Corporation, and Export-Import Bank of China.[4]: 221

In 2015, China used its foreign exchange reserves to recapitalize CDB, which in turn empowered it to make significant foreign loans.[8]: 70

In 2017, CDB provided RMB 130 billion to fund infrastructure and environmental upgrading in Xiong'an.[16]: 155

As of December 2018, outstanding loans to 11 provincial-level regions along the belt amounted to 3.85 trillion yuan (about 575 billion U.S. dollars), according to the CDB. New yuan loans to these regions reached 304.5 billion yuan last year, accounting for 48 percent of the bank's total new yuan loans. The funds mainly went to major projects in the fields of ecological protection and restoration, infrastructure connectivity, and industrial transformation and upgrading. The CDB will continue to support ecological protection and green development of the Yangtze River in 2019, said CDB Chairman Zhao Huan. China issued a development plan for the Yangtze River Economic Belt in September 2016 and a guideline for green development of the belt in 2017. The Yangtze River Economic Belt consists of nine provinces and two municipalities that cover roughly one-fifth of China's land. It has a population of 600 million and generates more than 40 percent of the country's GDP.[17]

As of at least 2018, CDB was the world's largest development bank, with total assets exceeding 16 trillion RMB.[18]: 101

In 2020, China joined the G20-led Debt Service Suspension Initiative, through which official bilateral creditors suspended debt repayments of 73 of the poorest debtor countries.[7]: 134 China did not include CDB loans as part of the initiative under the logic that CDB was a commercial lender rather than an official bilateral creditor.[7]: 135

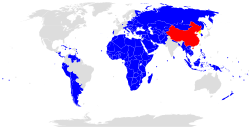

Along with the Silk Road Fund and the Export-Import Bank of China, the China Development Bank is one of the primary financing sources for Belt and Road Initiative projects in Africa,[19]: 245 and is an important funder of BRI projects more generally.[20]

Organizational structure

[edit]The Governors of the bank report to a Board of Supervisors, who are accountable to the central government. There are four vice governors and two assistant governors.[21] At the end of 2004, CDB had about 3,500 employees.[citation needed] About 1,000 of CDB's employees work at the Beijing Headquarters, with the rest in 35 mainland branches; including a representative office in Tibet and a branch in Hong Kong.[citation needed]

As of 2021, the CDB has more than 9,000 employees.[1]

CDB does not accept deposits from individuals.[7]: 39 Its depositors are other financial agencies that are collaborating with CDB or entities which are repaying loans borrowed from CDB.[7]: 39

Ownership

[edit]CDB is wholly state-owned through multiple state bodies.[7]: 85 As of 2019, the owners were Central Huijin Investment Ltd. (one of China's sovereign funds), Buttonwood Investment Holding Company Ltd. (owned by the State Administration of Foreign Exchange), and the National Council for Social Security Fund.[7]: 85

Subsidiaries and other ventures

[edit]In 2018, CDB was among the Chinese banks which launched the China-Arab Bank Consortium.[22]

Leadership

[edit]

CDB has a thirteen-member board of directors.[7]: 84 Three are the executives in charge of managing CDB.[7]: 84 Six are directors from the agencies that hold shares of CDB.[7]: 84 The four "government-ministry directors" come from the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Commerce, and the People's Bank of China.[7]: 84

List of governors

[edit]| Name (English) | Name (Chinese) | Tenure begins | Tenure ends | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yao Zhenyan | 姚振炎 | March 1994 | March 1998 | [7]: 83 |

| Chen Yuan | 陈元 | March 1998 | September 2008 | [7]: 83 |

| Jiang Chaoliang | 蒋超良 | September 2008 | November 2011 | |

| Zheng Zhijie | 郑之杰 | October 2012 | October 2019 | |

| Ouyang Weimin | 欧阳卫民 | October 2019 | May 2023 | |

| Tan Jiong | 谭炯 | May 2023 |

List of chairmen of the board

[edit]| Name (English) | Name (Chinese) | Tenure begins | Tenure ends | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen Yuan | 陈元 | September 2008 | April 2013 | |

| Hu Huaibang | 胡怀邦 | April 2013 | September 2018 | [7]: 83 |

| Zhao Huan | 赵欢 | September 2018 | [7]: 83 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "About China Development Bank 2021". www.cdb.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-06-22. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ CDB History Archived Archived 2005-07-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Michael Forsythe, Henry Sanderson (June 2011). "Financing China Costs Poised to Rise With CDB Losing Sovereign-Debt Status". Bloomberg Market Magazine.

- ^ a b Lin, Shuanglin (2022). China's Public Finance: Reforms, Challenges, and Options. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-09902-8.

- ^ "China Development Bank International Investment Limited - Investor Relations". cdb-intl.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-21. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "China Development Bank International Investment Limited - Portfolio". cdb-intl.com. 2019-08-30. Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Chen, Muyang (2024). The Latecomer's Rise: Policy Banks and the Globalization of China's Development Finance. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501775857. JSTOR 10.7591/jj.6230186.

- ^ a b Liu, Zongyuan Zoe (2023). Sovereign Funds: How the Communist Party of China Finances its Global Ambitions. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. doi:10.2307/jj.2915805. ISBN 9780674271913. JSTOR jj.2915805. S2CID 259402050.

- ^ "Annual report" (PDF). www.cdb-intl.com. 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Handbook of China's Financial System1/61 Chapter 6: Bond MarketHandbook on China's Financial System" (PDF). www.zhiguohe.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Annual report" (PDF). www.cdb-intl.com. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Annual report" (PDF). www.cdb-intl.com. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Lewis, Joanna I. (2023). Cooperating for the Climate: Learning from International Partnerships in China's Clean Energy Sector. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-54482-5.

- ^ a b Zhang, Angela Huyue (2024). High Wire: How China Regulates Big Tech and Governs Its Economy. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197682258.001.0001. ISBN 9780197682258.

- ^ Hu, Richard (2023). Reinventing the Chinese City. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21101-7.

- ^ Wang, Ling; Lee, Shao-ju; Chen, Ping; Jiang, Xiao-mei; Liu, Bing-lian (2016-06-20). Contemporary Logistics in China: New Horizon and New Blueprint. Springer. p. 124. ISBN 9789811010521.

- ^ Lan, Xiaohuan (2024). How China Works: An Introduction to China's State-led Economic Development. Translated by Topp, Gary. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-0080-6. ISBN 978-981-97-0079-0.

- ^ Murphy, Dawn (2022). China's Rise in the Global South: the Middle East, Africa, and Beijing's Alternative World Order. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-3009-3.

- ^ Curtis, Simon; Klaus, Ian (2024). The Belt and Road City: Geopolitics, Urbanization, and China's Search for a New International Order. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 167. doi:10.2307/jj.11589102. ISBN 9780300266900. JSTOR jj.11589102.

- ^ China Development Bank

- ^ Zhang, Chuchu (2025). China's Changing Role in the Middle East: Filling a Power Vacuum?. Changing Dynamics in Asia-Middle East Relations series. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-032-76275-3.

External links

[edit]China Development Bank

View on GrokipediaHistory

Establishment and Initial Mandate (1994–Early 2000s)

The China Development Bank (CDB) was established on 17 March 1994 pursuant to a special decree issued by the State Council of the People's Republic of China, functioning as a state-owned policy bank alongside the Export-Import Bank of China and the Agricultural Development Bank of China.[10][11] This creation addressed the inefficiencies in China's banking system, where state-owned commercial banks had been burdened with non-performing loans from directed policy lending for infrastructure and heavy industry; the policy banks were thus separated to handle such developmental financing explicitly, allowing commercial institutions to prioritize profitability.[12][13] The CDB's initial mandate emphasized medium- and long-term wholesale lending to support national economic priorities, targeting sectors such as infrastructure development, basic industries (including energy, transportation, and raw materials), and strategic projects to enhance competitiveness and public welfare.[14][15] Unlike commercial banks, it operated under government directives rather than pure market principles, with funding derived from bond issuances, deposits, and state support to finance large-scale endeavors aligned with Five-Year Plans.[11][12] In its early operations through the late 1990s and into the early 2000s, the CDB concentrated on domestic projects, providing financing for initiatives like power generation facilities, highways, and urban development to drive industrialization and regional balancing.[14][15] However, it encountered significant hurdles, including rapid accumulation of bad loans from politically directed lending, placing it near insolvency by the late 1990s, which necessitated subsequent recapitalization and reforms to stabilize operations while adhering to its developmental role.[16][13] By the early 2000s, amid China's accession to the World Trade Organization, the bank began tentative international extensions but remained predominantly focused on internal growth financing.[17][15]Reforms, Recovery, and Expansion (Mid-2000s–2010s)

In the mid-2000s, the China Development Bank (CDB) addressed elevated non-performing loans stemming from its policy lending role in infrastructure and heavy industry projects during the 1990s and early 2000s. By 2002, CDB collaborated with UBS Warburg to manage and dispose of approximately RMB 40 billion in distressed assets, marking an early effort to strengthen balance sheet recovery through securitization and international partnerships.[18] These measures aligned with broader Chinese banking sector initiatives to offload NPLs via asset management companies, reducing CDB's exposure and improving operational efficiency ahead of deeper structural changes.[19] A pivotal reform occurred in 2008, when the State Council approved CDB's transformation from a pure policy bank into a state-owned commercial entity, enabling it to pursue profit-oriented operations while retaining a developmental mandate.[20] This shift, formalized by December 2008 through incorporation as the China Development Bank Corporation, allowed CDB to issue marketable financial bonds without implicit sovereign guarantees, fostering market discipline and access to diverse funding sources.[21] The reform addressed prior vulnerabilities, such as reliance on low-cost policy financing, by emphasizing risk management and commercial viability, though it risked higher funding costs as bond ratings adjusted to reflect commercial status.[22] Post-reform, CDB expanded aggressively in the 2010s, with total assets surpassing $1 trillion by 2013 and reaching $3 trillion by the mid-decade, driven by domestic infrastructure financing and international outreach.[23] Internationally, lending surged from 2005 onward, financing over 200 projects across 18 Latin American countries by the early 2010s, including a $30 billion credit line to Venezuela in 2010 for oil-backed infrastructure.[24] This growth supported China's "Going Out" strategy, channeling funds into energy, transportation, and resource sectors abroad, while domestically prioritizing urbanization and high-speed rail, with loan disbursements exceeding RMB 10 trillion annually by 2015. The expansion, however, amplified risks from opaque lending practices and geopolitical dependencies, as evidenced by subsequent debt sustainability concerns in recipient nations.[25]Recent Operations and Policy Shifts (2020s)

In the early 2020s, the China Development Bank (CDB) adjusted its international operations amid global economic disruptions and evolving strategic priorities, with overseas development loans from China's two primary policy banks, including CDB, totaling just $10.5 billion across 28 new commitments in 2020 and 2021—the lowest volume in over a decade.[26][27] This contraction reflected Beijing's deliberate pivot from financing large-scale, resource-intensive projects, particularly in oil and gas, toward smaller-scale, sustainability-focused initiatives dubbed "small and beautiful" under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[28] By 2021, commitments to emerging economies alone fell to $3.7 billion, a 13-year low, driven by heightened scrutiny on debt sustainability and environmental impacts in recipient countries.[28] Domestically, CDB ramped up support for pandemic recovery and infrastructure stabilization, issuing loans for flood relief in July 2020 amid widespread natural disasters exacerbating COVID-19 effects.[29] The bank maintained its role in financing key sectors like transportation, energy, and urban development, while navigating China's property sector challenges, where policy banks like CDB hold significant exposure to real estate-linked projects.[5] Policy emphasis shifted toward green financing, with CDB pledging expanded credit for energy conservation, emissions reduction, afforestation, and disaster mitigation by June 2024 to advance the "beautiful China" ecological agenda.[30] Under the BRI framework, CDB integrated stricter environmental guidelines following December 2020 regulatory updates, prioritizing low-carbon infrastructure and aligning with Paris Agreement commitments, though overall lending volumes remained subdued into the mid-2020s due to fiscal caution and geopolitical tensions.[31] This evolution underscores CDB's adaptation to domestic economic deceleration—growth slowed to 4.7% in Q2 2024 and 4.6% in Q3—and a broader policy reorientation from expansionary credit to risk-managed, quality-focused development finance.[32]Mandate and Core Functions

Policy Bank Role and Objectives

The China Development Bank (CDB), established on March 17, 1994, by special decree of the State Council, functions as China's sole statutory policy-oriented financial institution at the ministry level, wholly owned by the central government.[11] Unlike commercial banks, which prioritize profitability and risk-adjusted returns, CDB's core role is to implement national macroeconomic policies through medium- and long-term financing for projects aligned with state development strategies, mobilizing domestic and international resources via bond issuance and lending rather than deposit-taking.[11][33] This policy bank mandate emphasizes non-profit-driven support for strategic national priorities, including guarantees, investment, and advisory services to guide fixed-asset investments and resource allocation.[11] As of December 31, 2004, approximately 99.1% of its outstanding loans, totaling RMB 1,397.3 billion, were directed toward infrastructure and foundational industrial projects, underscoring its focus on long-term economic structuring over short-term commercial viability.[11] CDB's primary objectives center on fostering sustainable economic growth by financing large-scale infrastructure, basic industries, and pillar sectors such as transportation, electric power, telecommunications, and petrochemicals, while promoting balanced regional development and addressing economic weaknesses.[11] It supports the government's medium- and long-term plans by channeling funds into key construction projects that commercial lenders may deem too risky or unprofitable, thereby enabling rapid industrialization and urbanization.[33] In recent years, this has extended to bolstering scientific and technological innovation, green development, and high-quality economic expansion, with initiatives like specialized loan schemes for basic research and low-carbon projects reinforcing its role in state-directed priorities.[10] By issuing policy-oriented bonds—reaching RMB 20 trillion cumulatively by 2020—CDB guides social capital toward national focal areas, including poverty alleviation and industrial upgrading, without the profit constraints typical of market-driven banking.[34][10] Overall, CDB operates as a development finance instrument to execute central directives, providing concessional or directed lending that aligns private sector activities with public policy goals, such as enhancing energy security, transport networks, and strategic industries essential for China's economic resilience and global competitiveness.[14] This role has evolved to include international dimensions, but domestically remains anchored in supporting macroeconomic stability and targeted growth sectors, as evidenced by its extension of RMB 650 billion in loans in 2021 for innovation and infrastructure.[35][11]Domestic Financing Priorities

The China Development Bank (CDB) directs the majority of its domestic lending toward medium- and long-term financing for infrastructure projects that address economic bottlenecks and support national strategic priorities, including transportation, energy, and urban development.[4][5] In 2024, CDB disbursed nearly 267 billion yuan to 102 key nationwide projects focused on network-type infrastructure in transportation, energy, water resources, digital development, and logistics.[36] This emphasis stems from CDB's mandate as a policy bank to bolster macroeconomic stability and economic lifelines, with infrastructure loans often comprising over 65% of monthly medium- and long-term disbursements, as seen in early 2023 when 137.8 billion yuan targeted such areas.[37] Key subsectors include transportation infrastructure, where CDB has financed major initiatives in railways, highways, waterways, urban transit, and airports.[38] For instance, in recent years, the bank has issued loans totaling 1.53 trillion yuan for projects encompassing industrial upgrading and urban development alongside transport networks.[39] Energy financing prioritizes power generation and grid enhancements, contributing to alleviating domestic supply constraints.[14] These efforts align with China's five-year plans, channeling funds to high-priority government initiatives that enhance connectivity and industrial capacity without relying on short-term commercial lending models. CDB also emphasizes green and sustainable development, leading domestic banks in green loan balances, which reached 2.3 trillion yuan by July 2021, with ongoing support for clean energy infrastructure, ecological protection, and pollution control.[40] This includes financing across sectors for renewable energy projects and energy conservation, reflecting a strategic shift toward environmental goals amid national policies for carbon neutrality.[5][14] Additional priorities encompass advanced manufacturing and inclusive finance, with loans extended to small and micro enterprises to foster technological self-reliance and regional equity.[37] In 2021, CDB increased domestic RMB loans by 1 trillion yuan to over 2.85 trillion yuan total, targeting these areas to improve livelihoods and guide private investment.[41] Overall, domestic operations reinforce CDB's role in sustaining high-quality growth, with total CNY loans rising 650 billion yuan in 2021 alone to support urbanization and key industries.[35]International Development Finance

The China Development Bank (CDB) extends international development finance primarily through medium- and long-term loans, equity investments, and syndicated facilities targeted at infrastructure, energy, transportation, and resource extraction projects in developing economies. These activities support China's strategic interests, including resource security, market access for Chinese firms, and geopolitical influence via initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Unlike multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, CDB lending often features resource-backed terms, where repayments are secured by commodities like oil or minerals, and emphasizes co-financing with Chinese state-owned enterprises. By prioritizing projects aligned with national priorities, CDB has positioned itself as the largest Chinese financier for overseas cooperation, with commitments channeled through direct lending and subsidiaries.[33][42] CDB's international portfolio expanded significantly post-2008, coinciding with China's global economic outreach. As of 2015, outstanding overseas loans reached $210 billion, reflecting a focus on high-return sectors amid domestic credit constraints. Under the BRI framework, launched in 2013, CDB has financed over 1,300 projects by the end of 2022, covering construction, energy, and connectivity in more than 100 countries, often in partnership with the Export-Import Bank of China. Annual commitments vary with global conditions; for instance, CDB participated in BRI-related engagements totaling tens of billions in sectors like power and rail, though exact breakdowns remain partially opaque due to commercial confidentiality. This financing has enabled rapid project execution but raised concerns over debt sustainability in recipient nations, as evidenced by restructurings in cases like Angola and Venezuela.[42][43][44] Notable examples illustrate CDB's approach. In September 2015, CDB provided a $5 billion loan to Venezuela's state oil company PDVSA for field development and upgrades, structured with a 10-year maturity and repayments via discounted oil shipments, part of a broader $10 billion package. Similarly, in December 2015, CDB committed $10 billion to Angola for oil sector recapitalization and infrastructure, repayable against future petroleum exports amid the country's fiscal crisis. In emerging Asia, CDB extended a $170 million loan in 2016 for the construction of Xiamen University's Malaysia campus, including academic facilities and dormitories. More recently, on March 18, 2020, CDB signed a $500 million foreign currency term facility with Sri Lanka to bolster reserves during the COVID-19 downturn. These loans typically carry interest rates around 4-6% and maturities of 10-15 years, differing from concessional aid by emphasizing commercial viability.[45][46][47][48] CDB's global presence is bolstered by overseas branches in hubs like London, New York, and Hong Kong, facilitating deal structuring and risk mitigation through tools like export credit insurance. While data from trackers like AidData document over 1,000 CDB-linked projects since 2000, totaling hundreds of billions in commitments, official figures understate "hidden" debts hidden in balance sheets of state firms, potentially exceeding $200 billion by 2016 across Chinese lenders. This model has driven infrastructure gaps closure in recipients but invites scrutiny for opacity and alignment with host governance standards, contrasting transparent multilateral norms.[49][50]Organizational Framework

Ownership, Governance, and Regulation

The China Development Bank (CDB) operates as a wholly state-owned policy bank under the direct leadership of the State Council of the People's Republic of China.[51] Its ownership structure reflects centralized state control, with the Ministry of Finance holding 36.54% of shares, Central Huijin Investment Ltd.—a subsidiary of the sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation—owning 58.21%, and the remaining stakes distributed among other state-affiliated entities such as social security funds.[14][1] This configuration ensures that equity is predominantly vested in government organs, aligning the bank's operations with national policy objectives rather than commercial profit maximization.[13] Governance at CDB is structured hierarchically to maintain accountability to central authorities. The bank is led by a chairman and president appointed by the State Council, supported by a board of directors comprising executive members responsible for daily management, non-executive directors representing major shareholders, and representatives from supervising government ministries.[13] A board of supervisors oversees the directors, with governors and vice governors reporting directly to this body, which in turn is accountable to the central government; as of recent structures, there are typically four vice governors and two assistant governors handling specialized portfolios such as international finance and risk management.[13] Senior management, spanning 29 internal departments, executes directives under this framework, prioritizing state-directed development lending over independent shareholder influence.[13] Regulation of CDB falls under the National Financial Regulatory Administration (NFRA), which succeeded the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC) in 2023 and enforces prudential standards across policy and commercial banks.[52] The NFRA mandates CDB to maintain a capital adequacy ratio (CAR) as its core regulatory metric, alongside requirements for triennial business assessments and adjustments to align with evolving national priorities.[53][54] Specialized measures, such as the "Measures for the Supervision and Administration of China Development Bank," govern its operations, emphasizing risk monitoring and off-site supervision while accommodating its policy bank status, which grants exemptions from certain commercial banking constraints like deposit-taking prohibitions.[54][13] This supervisory regime integrates CDB into China's broader financial stability framework but subjects it to less stringent enforcement compared to purely commercial entities, reflecting its role in executing state imperatives.[13]Structure, Subsidiaries, and Global Presence

The China Development Bank (CDB) maintains a hierarchical organizational structure centered on its Beijing headquarters, which houses core departments responsible for policy formulation, risk management, and operational oversight, including a four-tier risk management framework involving the board of directors, senior management, business departments, and branches. This setup supports its role as a policy bank, with specialized units for domestic lending, international finance, and equity investments. As of recent reports, CDB employs over 10,000 staff, with around 1,000 at headquarters and the remainder distributed across its domestic and international network.[11][10] Domestically, CDB operates 37 primary branches and four secondary branches across mainland China, covering major provinces and regions to facilitate infrastructure and development financing, alongside a representative office in Tibet. It also maintains an offshore branch in Hong Kong to handle international transactions and cross-border activities. These branches focus on medium- and long-term lending aligned with national priorities such as energy, transportation, and urban development.[2][55] CDB's subsidiaries include specialized entities such as China Development Bank Capital Corporation Limited (CDB Capital), which manages equity investments and funds; China Development Bank Securities Co., Ltd., focused on securities and capital markets; China Development Bank Financial Leasing Co., Ltd., providing leasing services for equipment and infrastructure; and the China-Africa Development Fund, dedicated to investments in African projects. These subsidiaries, numbering around five in total, extend CDB's capabilities into non-lending areas like private equity and regional development funds, often operating semi-independently while aligned with the parent bank's mandate.[56][14] For global presence, CDB has expanded through 11 overseas representative offices as of 2023, located in key cities including London, Moscow, Cairo, Rio de Janeiro, Caracas, and Minsk, to support international lending and Belt and Road Initiative projects. These offices primarily engage in project appraisal, partnership building, and market intelligence rather than full banking operations, reflecting CDB's strategy of resource mobilization abroad while prioritizing concessional financing for strategic infrastructure in developing regions.[2][57][15]Leadership and Key Personnel

Governors and Chairmen

The China Development Bank (CDB) is governed by a chairman, who serves as the primary executive leader and party secretary, and a president (行长), responsible for operational management, with both positions appointed by the State Council under the leadership of the Communist Party of China Central Committee.[10] These roles have evolved since the bank's founding, reflecting shifts in policy priorities from domestic infrastructure to international development finance. Yao Zhiyan served as the inaugural president from the bank's establishment on March 17, 1994, until 1998, overseeing initial setup and early lending for national projects. Chen Yuan, son of senior Communist leader Chen Yun, succeeded as president in April 1998 and held the position until May 2013, also assuming the chairmanship around 2000–2008 during a period of rapid expansion in the bank's assets and global outreach.[58][59] Under Chen, CDB's loan portfolio grew significantly, funding key infrastructure like the Three Gorges Dam and early overseas initiatives, though this era later drew scrutiny for risk accumulation in state-directed lending.[59] Hu Huai Bang replaced Chen as chairman in April 2013, serving until his dismissal in September 2018 amid a Central Commission for Discipline Inspection probe into "serious violations of discipline," including corruption allegations tied to lending approvals during his prior role at Bank of Communications.[60][61][62] Zhao Huan, formerly with China Construction Bank, has chaired CDB since November 2018, emphasizing alignment with national strategies like dual circulation and Belt and Road support.[63] Post-Chen presidents have included figures focused on risk management and international expansion; Ouyang Weimin acted as president by 2022, directing efforts in regional development like Ningxia's infrastructure. Tan Jiong, previously at the Ministry of Finance, was appointed vice chairman and president in May 2023, continuing oversight of policy-aligned financing amid economic slowdowns.[63] Leadership transitions often coincide with broader anti-corruption campaigns and policy recalibrations, underscoring CDB's role as a state instrument rather than an independent entity.[61]Influential Figures and Decision-Making

Chen Yuan, who served as chairman of the China Development Bank (CDB) from 1998 to 2013, was instrumental in reshaping the institution from a struggling entity into a globally influential development finance provider. Under his leadership, CDB shifted toward commercial operations, achieving profitability through diversified lending in infrastructure, energy, and overseas investments, while amassing assets exceeding $1 trillion by 2013.[13] His background as deputy governor of the People's Bank of China and son of revolutionary leader Chen Yun provided leverage to navigate political constraints, enabling aggressive expansion aligned with state priorities like resource security.[64] Subsequent chairmen faced challenges amid anti-corruption drives and economic shifts. Hu Huaibang, chairman from 2013 to 2018, oversaw continued growth in policy lending but was investigated for serious disciplinary violations in July 2019 by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, highlighting risks of elite capture in state-directed finance.[65] Zhao Huan, appointed chairman and party secretary in November 2018, previously led the Agricultural Bank of China; his tenure emphasizes risk management and alignment with "high-quality development" under Xi Jinping's directives, including Belt and Road Initiative financing.[66] Vice Chairman and President Tan Jiong, in role since May 2023, supports operational execution in domestic and international portfolios.[63] CDB's decision-making integrates corporate governance with party-state oversight, reflecting its status as a policy bank under the State Council. The board of directors, comprising 13 members including three executive directors (chairman, vice chairman, and others), four from government agencies, and independents, approves major strategies and risks; it is accountable to a board of supervisors for compliance.[14][10] Senior management, overseeing 29 departments, handles loan approvals within predefined policy areas like infrastructure and strategic industries, conducting independent risk assessments often backed by state insurers for high-exposure projects.[13][67] Ultimate authority resides with the Communist Party committee, ensuring decisions prioritize national objectives over short-term profitability, as evidenced by 2013 reforms that formalized a "four-tier" risk framework while retaining policy mandates.[10] This structure enables rapid mobilization for state goals but exposes CDB to non-commercial risks, such as opaque overseas deals.[14]Economic Contributions and Achievements

Role in China's Infrastructure and Growth

The China Development Bank (CDB), established as a policy-oriented financial institution in 1994, has provided critical medium- and long-term financing for domestic infrastructure projects, targeting sectors such as transportation, energy, and urbanization to alleviate economic bottlenecks and support sustained growth.[68] By extending loans for large-scale initiatives that commercial banks often avoid due to extended repayment horizons and perceived risks, CDB has enabled the state to direct capital toward productive assets, fostering industrialization and regional integration.[5] This approach has aligned with national five-year plans, prioritizing investments that enhance logistical efficiency and capacity expansion, which in turn have underpinned China's average annual GDP growth exceeding 9% from 1994 to 2010.[13] In the transportation domain, CDB has financed extensive networks of railways, highways, waterways, and urban transit systems, with loans supporting major projects that improved inter-provincial connectivity and reduced logistics costs.[38] For instance, from January to May 2023, the bank extended 268.7 billion yuan (approximately $37.78 billion) specifically for transport infrastructure construction.[69] In 2024, CDB disbursed 1.53 trillion yuan (about $213.37 billion) in nationwide infrastructure loans, a substantial portion directed toward transport and energy facilities that bolstered supply chains and industrial output.[39] These efforts have contributed to China's emergence as a global leader in high-speed rail mileage, exceeding 40,000 kilometers by 2023, by funding track expansions and electrification that facilitated labor mobility and merchandise flows critical to export-led growth.[14] CDB's infrastructure lending has also extended to energy projects, including power generation and grid enhancements, which have ensured reliable supply for manufacturing hubs and urban centers amid rapid electrification demands.[68] By August 2025, the bank's outstanding medium- and long-term loans for infrastructure surpassed 6 trillion yuan ($843.81 billion), reflecting cumulative commitments that have driven fixed-asset investment as a key engine of economic expansion.[70] This financing model, backed by low-cost policy funding and government directives, has accelerated urbanization— with over 60% of the population urbanized by 2020—while amplifying multiplier effects on employment and ancillary industries, though it has raised concerns about long-term debt sustainability not directly tied to revenue-generating assets.[5] Overall, CDB's role has been instrumental in translating state priorities into tangible capacity buildup, enabling China to achieve middle-income status through infrastructure-led development.[13]Support for Strategic Initiatives like BRI

The China Development Bank (CDB) has served as a primary financier for China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, by extending policy-oriented loans to infrastructure, energy, and capacity-building projects in participating countries. These efforts align with Beijing's strategic objectives of enhancing connectivity, trade routes, and resource access, with CDB leveraging its development banking model to mobilize capital for large-scale endeavors often involving Chinese state-owned enterprises. By the end of 2017, CDB's cumulative loans to BRI countries surpassed 180 billion USD, representing about 30% of its international business portfolio at that time.[6] In May 2017, during the second Belt and Road Forum, CDB committed 250 billion RMB (approximately 36 billion USD) in special loans specifically earmarked for BRI priorities: 100 billion RMB for infrastructure connectivity, 100 billion RMB for production capacity cooperation, and 50 billion RMB for financial collaboration. That year alone, CDB disbursed 17.6 billion USD in loans to BRI countries for sectors including infrastructure, telecommunications, industrial parks, and energy. Outstanding loans for BRI-related international cooperation projects reached 312.4 billion USD by early 2019, while cumulative lending since the initiative's inception exceeded 260 billion USD as of mid-2021.[6][71][72] Notable examples include CDB's medium- and long-term financing in September 2013 for the Garmensh natural gas field project in Turkmenistan, operated by China National Petroleum Corporation, which supports annual production of 30 billion cubic meters of gas to bolster energy security along BRI pipelines. In June 2016, CDB participated in syndicated loans for the 1.5 billion USD Jinnah International Photovoltaic Industrial Park in Pakistan, a 900 MW solar facility that marked an early BRI push into renewable energy cooperation. More recently, CDB contributed to the Jakarta-Bandung High-Speed Railway in Indonesia, a flagship 142 km project completed in 2023, exemplifying rail infrastructure financing under the initiative.[6][73]Criticisms, Risks, and Controversies

Debt Practices and Borrower Sustainability

CDB's overseas lending, primarily through policy-oriented loans for infrastructure and resource projects, emphasizes commercial viability over comprehensive debt sustainability assessments, often prioritizing project-level returns secured by collateral such as commodities or assets rather than borrowers' overall fiscal capacity.[42] These loans typically carry interest rates of approximately 5% (around 2% above six-month LIBOR), with grace periods of about 4 years and maturities averaging 13 years, terms that are less concessional than those from the World Bank or IMF and impose relatively rapid repayment pressures on low-income borrowers.[42] [74] Unlike multilateral lenders, CDB financing frequently lacks public transparency on terms, includes strict confidentiality clauses, and favors Chinese state-owned enterprises as contractors, which can inflate costs and limit local economic spillovers, thereby straining borrower budgets without proportional developmental benefits.[75] This approach has contributed to elevated debt vulnerabilities in recipient countries, where CDB loans—often extended to sovereigns or state-owned entities—account for a significant share of hidden or off-balance-sheet liabilities not captured in official debt statistics.[76] For instance, AidData estimates unreported debt to Chinese institutions, including CDB, at $385 billion globally as of recent analyses, representing a gap between official figures and actual exposures that exacerbates sustainability risks by delaying recognition of over-indebtedness.[76] In Africa, CDB's state-backed bilateral lending has been linked to distress in nations like Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where commodity price volatility amplified repayment challenges on infrastructure loans tied to resource exports.[77] Similarly, CDB provided $50 billion in loans to Venezuela from 2001 to 2015, collateralized by oil revenues, which intensified fiscal strain amid declining exports and contributed to multiple defaults without substantial debt relief from China.[78] Empirical data underscore broader patterns: as of 2021, over 60% of China's overseas lending portfolio, with CDB as a primary actor, was owed by countries in arrears, restructuring, or conflict, driven by factors including high interest rates, short maturities (often under 10 years on average), and exposure to external shocks like commodity busts or rising global rates.[79] [80] In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 40% of debt to China—much financed by CDB—resides in countries classified by the World Bank as in or at high risk of debt distress, with limited evidence of rigorous ex-ante sustainability analyses comparable to IMF debt sustainability frameworks.[81] China's adoption of a debt sustainability framework in 2019, modeled partly on World Bank and IMF standards, has yielded uneven application, with reluctance to provide permanent haircuts or integrate into multilateral restructurings, often resulting in rollovers that defer rather than resolve burdens.[82] [83]| Borrower Example | CDB Loan Exposure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Venezuela | $50 billion (2001–2015), oil-collateralized | Contributed to serial defaults and economic collapse; minimal permanent relief.[78] |

| Sudan | $1.5 billion (2012) to state oil firm | Hidden debt elevated total liabilities; repayment tied to petroleum exports amid sanctions.[76] |

| Zambia | Significant infrastructure loans (pre-2020) | Debt distress declaration in 2020; Chinese lending, including CDB, complicated G20-led restructuring.[84] [85] |