Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chinese musical notation

View on Wikipedia

Systems of musical notation have been in use in China for over two thousand years. Different systems have been used to record music for bells and for the Guqin stringed instrument. More recently a system of numbered notes (Jianpu) has been used, with resemblances to Western notations.

Ancient

[edit]The earliest known examples of text referring to music in China are inscriptions on musical instruments found in the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (d. 433 B.C.). Sets of 41 chime stones and 65 bells bore lengthy inscriptions concerning pitches, scales, and transposition. The bells still sound the pitches that their inscriptions refer to. Although no notated musical compositions were found, the inscriptions indicate that the system was sufficiently advanced to allow for musical notation. Two systems of pitch nomenclature existed, one for relative pitch and one for absolute pitch. For relative pitch, a solmization system was used.[1]

Guqin notations

[edit]The earliest music notation discovered is a piece of guqin music named Jieshi Diao Youlan (碣石調·幽蘭) during the 6th or 7th century. The notation is named "Wenzi Pu", meaning "written notation".

The tablature of the guqin is unique and complex. The older form is composed of written words describing how to play a melody step-by-step using the plain language of the time, i.e. descriptive notation (Classical Chinese). The early pieces of music are all written by words to explicitly explain the fingerings. Later on, to simplify the method of recording, "Jianzi Pu", which means "abbreviated character" notation, is invented in the late Tang dynasty by Cao Rou (曹柔), a famous Guqin player.

This newer form of guqin notation is composed of bits of Chinese characters put together to indicate the method of play is called prescriptive notation. Rhythm is only vaguely indicated in terms of phrasing. It is used to record fingering actions and string orders, without recording the pitch and tempo, thus make the piece look simpler and give more flexibility to guqin players.

Tabulatures for the qin are collected in what is called qinpu.

Gongche notation

[edit]Gongche notation, dating from the Tang dynasty, used Chinese characters for the names of the scale.

Octave positions are sometimes shown by the addition of an affix or small mark. A chromatic scale could be produced from this by the use of the prefixes gao- (high) to raise a note, or xia- (low) to lower it, by a semitone; but after the 11th century, gao- ceased to be used.[2]

Traditionally, the Gongche notation was written vertically from right to left, but horizontally is also accepted nowadays.

Additionally, this system was also introduced to Korea, aka gong jeok bo in ancient music, and also Kunkunshi, a Ryukyuan musical notation still in use for sanshin.[3]

Jianpu (numbered musical notation)

[edit]The Jianpu system uses numbers to notate music. It is common in East Asia, including Myanmar (Burma), Japan, Mainland China and Taiwan.

The notation was invented by Enlightenment thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau in 1742.[2] It had gained widespread acceptance by 1900.[citation needed] It uses a movable do system, with the scale degrees 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 standing for do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si, while rests are shown as a 0. Dots above or below a numeral indicate the octave of the note it represents. Key signatures, barlines, and time signatures are also employed. Many symbols from Western standard notation, such as bar lines, time signatures, accidentals, tie and slur, and the expression markings are also used. The number of dashes following a numeral represents the number of crotchets (quarter notes) by which the note extends.

| Note | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Solfege | do | re | mi | fa | sol | la | si |

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

The table above shows how the numbers represent the note respectively. The Jianpu uses dots above or below the number to show its octave. They also represent the number of octaves. For example, a dot below the number "6" is an octave lower than "6". It also uses dashes (–) to represent the note length.

References

[edit]- ^ Bagley, Robert (2004). "The Prehistory of Chinese Music Theory Archived 2008-06-09 at the Wayback Machine" (Elsley Zeitlyn Lecture on Chinese Archaeology and Culture), Britac.ac.uk.

- ^ a b editor., Tyrrell, John, 1942- Sadie, Stanley (2001). The new Grove dictionary of music and musicians. Oup USA. ISBN 9780195170672. OCLC 57201422.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Provine, Robert C. (2017-11-22). Provine, Robert C; Tokumaru, Yosihiko; Witzleben, J. Lawrence (eds.). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. doi:10.1201/9781315086507. ISBN 9781315086507.

Chinese musical notation

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Early Origins

The earliest evidence of Chinese musical notation emerges from archaeological discoveries dating to the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), particularly the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, excavated in 1978 near Suizhou, Hubei Province, and dated to approximately 433 BCE.[7] This tomb yielded an extraordinary ensemble of musical instruments, including a set of 65 tuned bronze bells (bianzhong) and 32 stone chimes (bianqing), which together represent the most complete surviving example of ancient Chinese court music apparatus. The instruments bear extensive inscriptions—totaling 3,755 characters, many inlaid with gold—that detail tuning specifications, pitch relationships, and performance guidelines, marking the inception of systematic notation in Chinese music history.[7] These inscriptions primarily denote absolute and relative pitches using specialized terminology derived from bell names, with "huangzhong" (yellow bell) serving as the foundational standard pitch, corresponding to a low tone often equated to modern G♯ or A♭.[8] The notations employ characters and numerical indicators to specify intervals within a 12-tone chromatic framework, though the underlying structure implies a pentatonic scale organized into modes (e.g., equivalents to do-re-mi-sol-la in Western solfège, such as huangzhong, taicu, guxi, and wuyi).[9] For instance, each bell and chime is labeled with its primary and secondary tones—produced by striking different parts of the instrument—along with references to regional tuning standards from states like Zeng, Chu, and Zhou, facilitating precise calibration during ensemble play. This system prioritized harmonic consonance and modal variety, reflecting the theoretical foundations of early Chinese music as outlined in later texts but evidenced here archaeologically.[10] In the context of Warring States ritual music, these notations functioned not as portable scores for composition but as practical engravings for instrument construction, tuning, and ritual performance, ensuring uniformity in ceremonial ensembles that accompanied state sacrifices and ancestral worship.[11] The bells and chimes, arranged in graduated sets on wooden frames, were struck in sequence to produce layered harmonies, with inscriptions guiding musicians on pitch placement and modal shifts to evoke cosmic order and political legitimacy.[7] This inscription-based approach laid the groundwork for later formalized notations during the Han dynasty and beyond.Evolution Through Dynasties

During the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the establishment of the Yuefu Music Bureau in 120 BCE represented a major advancement in musical documentation, as it systematically collected folk songs and poetry whose metrical structures implied rhythmic notations for accompaniment and performance. These Yuefu compositions, often chanted with music, preserved oral traditions in written form and emphasized rhythmic patterns tied to poetic lines. Complementing this, bamboo slips from the period, including examples from Han sites, describe ensemble scales based on the pentatonic system, offering early textual insights into coordinated group music for rituals and entertainment.[12][13][14] In the subsequent Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern dynasties (220–589 CE), musical theory shifted toward more abstract and systematic explorations, with texts emphasizing cyclical pitch systems derived from the 12 lü pipes, using mathematical ratios to approximate a chromatic scale and enable mode rotations. This period's theoretical works built on Han foundations by detailing how the lü pipes—starting from the foundational huangzhong pitch—generated a full chromatic cycle through proportional length adjustments, allowing for versatile ensemble tuning. The integration of Buddhism during these dynasties further enriched theory by introducing ritual elements that adapted cyclical systems to new devotional contexts.[14] The Sui and early Tang dynasties (581–907 CE) achieved greater institutionalization of musical notation within court rituals, standardizing symbols for the core modes—gong, shang, zhi, and yu—to guide large ensembles in performances of yayue ritual music. These notations, often comprising simple ideographic symbols indicating pitch and mode, ensured uniformity across imperial ceremonies involving dozens of musicians on wind, string, and percussion instruments. A key development was the influence of Buddhism and foreign exchanges via the Silk Road, which introduced exotic scales and timbres documented in foundational texts like the Yueji chapter of the Liji, providing cosmological justification for blending them with indigenous systems.[14][15]Guqin Notation

Principles and Symbols

Guqin notation employs a specialized tablature system tailored to the seven-stringed zither, prioritizing prescriptive instructions for fingering, string selection, and performance techniques over fixed pitches or rhythms. This approach distinguishes it from staff-based systems, focusing instead on guiding the player's physical interaction with the instrument to produce idiomatic sounds. The notation evolved historically from wenzi pu, a verbose descriptive form using full Chinese characters to detail actions, which emerged in the 6th to 7th centuries during the Sui and early Tang dynasties, to jianzi pu, a streamlined variant developed in the late Tang dynasty (around the 8th-9th centuries) by figures such as Cao Rou. Wenzi pu relied on lengthy textual explanations for each note, while jianzi pu condensed these into composite characters, enhancing readability and portability for solo performance.[16][17][18] In jianzi pu, the core symbol for each note is a numeric indicator for the string, numbered 1 through 7 from the thickest (lowest pitch) to the thinnest (highest pitch), often combined with characters specifying the left-hand finger position relative to the instrument's 13 hui (position markers). For instance, the left-hand component might include a finger identifier (e.g., symbols derived from "thumb" or "ring finger") followed by a hui number, such as the 7th hui on the 1st string, forming a ligature like a modified Chinese character. Right-hand techniques are denoted by affixes or surrounding radicals, drawing from a set of approximately 18 basic symbols for plucking actions, including gou (hook, downward stroke with thumb), ti (upward flick with index), mo (downward stroke with index), and pi (split, outward thumb motion). Harmonics are indicated by encircling the string number or using a dedicated symbol like fan (overtone), while slides and presses incorporate directional radicals. These elements cluster vertically or horizontally to form compact, readable notation.[17][18][19] Pitch in guqin notation is relative, defined within modal frameworks rather than absolute frequencies, allowing flexibility in tuning while maintaining intervallic relationships central to Chinese music theory. Modes such as gong (starting on the open 1st string as the tonic) or shang (emphasizing the 2nd string) guide the perceptual hierarchy, with the standard tuning (e.g., 5-6-1-2-3-5-6 in solfege) producing pentatonic structures across the strings. This contrasts with notations for instruments like bianzhong bells, which often specify fixed pitches via gongche symbols. Rhythm and duration are not rigidly quantified in traditional jianzi pu, leaving interpretation to the performer based on oral tradition; however, relative lengths may be suggested through horizontal lines or spacing between symbols, with longer lines implying sustained notes. Ornamentation, including vibrato (yinyin) and trills, is conveyed via auxiliary symbols or repeated radicals, while sectional tempo is marked by descriptive affixes such as man (slow) or kuai (fast), often appearing at the piece's outset or transitions.[18][19][16]| Category | Key Symbols/Examples | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Strings | 1–7 (numeric characters) | String selection, 1 (lowest) to 7 (highest) |

| Left-Hand Positions | 徽 (hui) + number (e.g., 七徽 for 7th hui); finger radicals (e.g., 拇 for thumb) | Pressing location relative to hui markers |

| Right-Hand Techniques | 勾 (gou), 挑 (ti), 抹 (mo), 剔 (te) | Plucking directions and manners (e.g., hook, flick, wipe, pick) |

| Harmonics/Open | Circle around number or 泛 (fan) | Open string or overtone production |

| Tempo Affixes | 慢 (man), 快 (kuai) | Slow or fast pace indicators |

Historical Examples

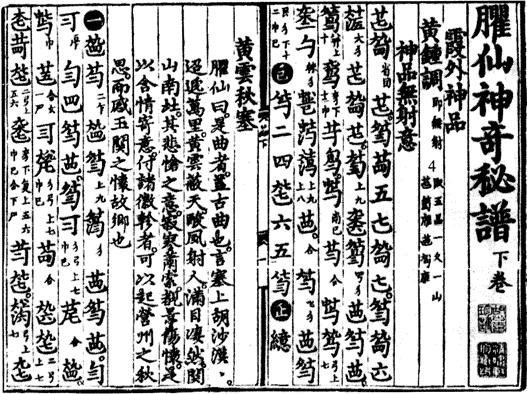

One of the earliest surviving examples of guqin notation is the score for Jieshi Diao Youlan (碣石調·幽蘭, "Solitary Orchid in the Jieshi Mode"), originating from the Tang dynasty in the 7th century CE and preserved in a manuscript now held by the Tokyo National Museum.[20] This piece, traditionally attributed to the scholar Qiu Ming (493–590 CE) during the Liang dynasty, employs the ancient wenzi pu (文字譜, "written notation") system, which uses descriptive Chinese characters to specify techniques such as right-hand plucking (bo 擘 for outward stroke and tiao 挑 for inward flick) on particular strings and left-hand harmonics (fan yin 泛音) at specific positions along the instrument's 13 hui (徽, studs).[21] For instance, a typical excerpt might read "乙十一" (yi shi yi), indicating a harmonic sounded by lightly touching the 11th hui on the second string while plucking, producing a resonant, ethereal tone that evokes the melody's contemplative mood.[20] This notation not only captures the piece's structure but also its poetic essence, drawing from Cao Zhi's ancient verse to symbolize isolation and natural harmony. A pivotal anthology illustrating the evolution of guqin notation is Shen Qi Mi Pu (神奇秘譜, "Wondrous and Secret Score"), compiled in 1425 CE during the Ming dynasty by Prince Zhu Quan (1378–1448).[22] This collection features 64 pieces, many composed or arranged by Zhu himself, and demonstrates the transition to more concise jianzi pu (減字譜, "reduced character notation"), where abbreviated symbols layer instructions for rhythm—often implied through repetition and grouping—mood via tuning modes (diao 調), and expressive effects like the "dragon chant" (long yin 龍吟), rendered with trilling harmonics and sliding tones symbolized by characters such as "龍" combined with position markers.[23] Pieces like Gaoshan (高山, "High Mountains") showcase these elements, with notations guiding performers to create cascading arpeggios that mimic flowing water and towering peaks, blending technical precision with emotional depth.[22] Zhu Quan's Shen Qi Mi Pu marked a key standardization of guqin notation in the early 15th century, refining approximately 19 core symbols for right-hand techniques (such as mo 抹 for inward stroke and gua 刮 for scraping) that became foundational for later handbooks and influenced Qing dynasty publications like Wuyin Qinpu (無射琴譜, 1722).[24] This codification facilitated wider dissemination among literati, ensuring consistency across regions and generations. Guqin notation has been instrumental in preserving the refined music of Chinese literati culture, safeguarding aesthetic ideals of subtlety and introspection against oral transmission's fragility; by the 19th century, over 1,000 unique pieces had been documented in various handbooks, forming a vast repertoire that reflects philosophical and poetic traditions.[25]Gongche Notation

Structure and Usage

Gongche notation employs a system of Chinese characters to denote pitches within the traditional pentatonic scale, primarily using characters such as 工 (gōng) for the first degree (do), 尺 (chě) for the second (re), 上 (shàng) for the third (mi), 凡 (fán) for the fifth (sol), 六 (liù) for the sixth (la), and 五 (wǔ) for the seventh (ti) in extended scales.[26] These characters cycle to represent higher or lower pitches, with dots placed above or below them to indicate octaves— a single dot for one octave above or below the central range, and multiple dots for further extensions. Additional symbols like 上 and 乙 extend for higher octaves. Rhythmic values are marked by horizontal lines or flags attached to the characters, where longer lines signify sustained notes and shorter ones indicate quicker durations, though exact interpretations can vary by regional practice; circles or other introductory symbols often denote beats and tempo.[26] This character-based approach allows for a compact, vertical writing style that aligns with classical Chinese script, facilitating its use in ensemble scores.[27] The notation originated during the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) as a simplified system for transcribing music in court ensembles, evolving from earlier informal notations used in banquet and ritual music.[26] Over subsequent dynasties, it incorporated additional symbols for accidentals to accommodate hexatonic or heptatonic scales, such as "pan" (攀), which raises the fourth degree to create a sharpened fa in certain modes. This development enabled greater expressive range while maintaining the pentatonic foundation, making it suitable for both fixed-pitch instruments and modal variations in imperial performances.[27] In vocal music traditions, gongche notation integrates directly with lyrics, where characters are inscribed alongside or above the text to guide pitch and rhythm, often specifying the starting mode (e.g., gong mode) and tempo through introductory symbols like circles for beats. For instance, in Kunqu opera scores such as those from "The Peony Pavilion," the notation aligns melodic lines with poetic verses, allowing singers to follow the undulating contours that evoke natural imagery while adhering to the specified rhythmic structure.[28] A defining feature of gongche notation is its cyclical design, where the sequence of characters shifts relative to the tonic to denote key or mode changes, functioning as a movable-do system that adapts to different pentatonic starting points without fixed pitch assignments.[26] This contrasts with Western solfège, which assigns consistent syllables to absolute pitches, enabling gongche to emphasize modal flexibility and contextual interpretation in performance.| Character | Pinyin | Scale Degree (Movable-Do) | Example Pitch Correspondence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 工 | gōng | 1 (do) | C |

| 尺 | chě | 2 (re) | D |

| 上 | shàng | 3 (mi) | E |

| 凡 | fán | 5 (sol) | G |

| 六 | liù | 6 (la) | A |

| 五 | wǔ | 7 (ti) | B |