Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

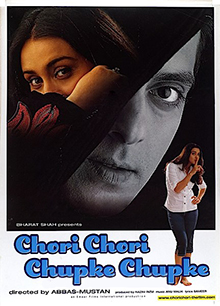

Chori Chori Chupke Chupke

View on Wikipedia

| Chori Chori Chupke Chupke | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Abbas–Mustan |

| Screenplay by | Javed Siddiqui |

| Story by | Neeraj Vora |

| Produced by | Nazim Rizvi |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Thomas A. Xavier |

| Edited by | Hussain A. Burmawala |

| Music by | Songs: Anu Malik Score: Surendra Sodhi |

Production company | Emaar Films International |

| Distributed by | Eros International |

Release date |

|

Running time | 165 minutes[1] |

| Country | India |

| Language | Hindi |

| Budget | ₹13 crore[2] |

| Box office | ₹37.5 crore (equivalent to ₹149 crore or US$18 million in 2023) [3] |

Chori Chori Chupke Chupke (transl. Secretly and Stealthily) is a 2001 Indian Hindi-language romantic drama film directed by Abbas–Mustan, with screenplay and story from Javed Siddiqui and Neeraj Vora respectively. Starring Salman Khan, Rani Mukerji and Preity Zinta in lead roles, the film's music is composed by Anu Malik and lyrics are penned by Sameer. Telling the story of a married couple hiring a young prostitute as a surrogate mother, the film generated controversy during its release for dealing with the taboo issue of surrogate childbirth in India.

Initially set to release on 22 December 2000, Chori Chori Chupke Chupke's release was delayed for several months when producer Nazim Rizvi and financier Bharat Shah were arrested and the Central Bureau of Investigation seized the film's prints on the suspicion that the production had been funded by Chhota Shakeel of the Mumbai underworld. The film was released in March 2001 to a wide audience and emerged as a commercial success, becoming the sixth highest-grossing film of 2001 in India.

Critical praise was majorly directed towards Zinta's performance as a prostitute-turned-surrogate mother, earning her a Best Supporting Actress nomination at the 47th Filmfare Awards, the only nomination for the film. The film has often been associated with surrogacy in Indian popular culture. This film was remade as a television drama series named Dil Se Dil Tak in which Sidharth Shukla portrayed as Raj, Rashami Desai as Priya and Jasmin Bhasin as Madhubala.

Plot

[edit]Raj and Priya, who come from well-to-do Indian families, meet at a wedding and fall in love. Soon after they marry, Priya becomes pregnant. Early in the pregnancy, Priya miscarries and becomes permanently infertile. On Dr. Balraj Chopra's advice, they decide to look for a surrogate mother to bear Raj's child and hide Priya's infertility from his conservative family. Since the process of artificial insemination could be revealed in the Indian media due to the family's renown and position in society, the couple agree that pregnancy should be achieved by means of sexual relations between Raj and the surrogate mother. Raj meets Madhubala "Madhu", a prostitute, who agrees to carry Raj's baby in exchange for money. After some much-needed behavioral grooming and a makeover, Madhu meets Priya—who is unaware of Madhu's background—and the three depart for Switzerland in order to carry out their plan secretly.

Soon Madhu is pregnant with Raj's child, and he happily tells his family that Priya is expecting. Meanwhile, Raj's business partner Ajay Sharma begins to sexually harass Madhu and she decides to leave Switzerland, mistakenly believing that Raj told his friend that she is a prostitute. Eventually, Priya finds out about Madhu's past, but still believes that Madhu should carry their child and begs her to stay. When Madhu is at home by herself, Raj's friend assaults her but Raj arrives in time to save her. Overwhelmed by Raj's kindness, Madhu falls in love with him.

Raj's family suddenly arrives in Switzerland. While Priya reaches for pregnancy-simulating pillows, the family meets the heavily pregnant Madhu who is introduced to them as a friend staying with them while her husband is travelling for business. Raj's grandfather Kailashnath and father Ranjit arrange a Godbharaai, a religious baby shower ceremony. They ask Raj, Priya, and Madhu to return with them to India, where the ritual must be held as formally required by tradition.

The ceremony is very important so Priya sends Madhu as herself. An emotional Madhu becomes conflicted about giving up her child. Finding Madhu's room empty and the money dumped on the bed, a frantic Priya pursues her to the train station and slaps Madhu when she confesses that she loves Raj. By the time Raj arrives, Madhu has gone into premature labour. The doctor announces that either Madhu or the child can be saved, and Priya asks him to save Madhu. However, both mother and baby survive. Frustrated, Madhu gives the baby to Priya, who quickly settles into a hospital bed with "her" baby. Dr. Balraj Chopra lies to Raj's family that while Priya gave birth, Madhu's child was stillborn.

When Madhu is ready to leave, she promises Raj that she will not go back to prostitution. When he takes her to the airport, he realizes that she loves him and kisses her forehead. Madhu leaves happily.

Cast

[edit]The cast is listed below:[4][5]

- Salman Khan as Raj Malhotra

- Rani Mukerji as Priya Malhotra

- Preity Zinta as Madhubala Singh "Madhu"

- Farida Jalal as Asha Malhotra

- Dalip Tahil as Ranjit Kumar Malhotra

- Johnny Lever as Pappu Bhai

- Amrish Puri as Kailashnath Malhotra

- Prem Chopra as Dr. Balraj Chopra

- Apara Mehta as a prostitute

- Ruby Bhatia as a news reporter

- Deepti Bhatnagar as a dancer in the song "Mehendi"

- Adi Irani as Ajay Sharma

Production

[edit]Director duo Abbas–Mustan had almost completed Ajnabee by October 1999 when they declared Chori Chori Chupke Chupke as their next project.[6] The three leads, Salman Khan, Rani Mukerji, and Preity Zinta, previously starred together in the romantic comedy Har Dil Jo Pyar Karega (2000).[6] Producer Nazim Rizvi clarified that the casting of the three actors happened before they signed for the latter film.[7] Khan, Mukerji and Zinta were paid ₹1.5 crore (US$180,000), ₹0.24 crore (US$28,000), and ₹0.25 crore (US$30,000) for their roles, respectively (all sums unadjusted for inflation).[8] Zinta was initially reluctant to play her role, as she was unsure she was suited to play a prostitute, but she eventually accepted it at the directors' persuasion. To prepare for it, she visited several bars and nightclubs in Mumbai's red-light areas to study the lingo and mannerisms of sex-workers.[9][10]

Chori Chori Chupke Chupke was made on a budget of ₹13 crore (equivalent to ₹52 crore or US$6.1 million in 2023).[2] Principal photography started in early 2000 and lasted two months.[4][8] Location filming, performed by Thomas A. Xavier, took place in both Mahabaleshwar and Switzerland.[11][12] The film was edited by Hussain A. Burmawala, and Surendra Sodhi composed the background score.[4][13]

Initially, Shah Rukh Khan was offered the lead role as Raj Malhotra, who had previously worked in the directors' two films Baazigar, and Baadshah. However, he declined due to lack of dates, and then Salman Khan was approached and has accepted the offer.

Themes and influence

[edit]The film generated some controversy before and during its release for being one of the only Hindi-language films dealing with the taboo issue of surrogate childbirth in India, in addition to prostitution in India.[14][15] Surrogacy in the film is not achieved through artificial insemination but sexual intercourse, and author Aditya Bharadwaj argued that the film draws an analogy between surrogacy and prostitution.[16] Anindita Majumdar, author of the book Surrogacy (2018), wrote, "In popular Indian culture, surrogacy has come to be associated with the 2001 Hindi language film Chori Chori Chupke Chupke".[17] According to author Daniel Grey, that Madhubala was a prostitute before becoming a surrogate "reinforces a stereotyped and erroneous popular association between the two roles that has contributed to considerable prejudice on the Subcontinent against women who act as surrogates".[18]

According to The Hindu, some of film's scenes were said to have been borrowed from Pretty Woman (1990) and the storyline inspired by Doosri Dulhan (1983).[19] According to Krämer, the similarities between Pretty Woman and Chori Chori Chupke Chupke are limited to replicated scenes in "merely one plot strand among many", in an otherwise different story.[20] In another book by Majumdar, Transnational Commercial Surrogacy and the (Un)Making of Kin in India (2017), she discusses the similarity between Chori Chori Chupke Chupke and Doosri Dulhan. Majumdar describes the surrogate mothers as "fallen women" who are first portrayed as aberrant women with no interest in motherhood, who gradually develop a sense of maternal instinct during the process of pregnancy.[21]

Anupama Chopra of India Today described Zinta's character of Madhubala as hooker with a heart of gold, as did academic Lucia Krämer.[22][20] Sociologist Steve Derné wrote in his book Globalization on the Ground: New Media and the Transformation of Culture, Class, and Gender in India that through the character of Madhubala, Chori Chori Chupke Chupke becomes one of the films which portray "excessively sexual, greedy women who are redeemed by being remade as consumers". Derné further credited the film with melding the stereotypical "heroine" and "vamp" roles of Hindi heroines in contrast to how they were portrayed in previous decades, describing Zinta as a "legitimate heroine" in the film.[23] S. Banaji spoke of a "transformation in the 'moral' consciousness of the prostitute".[24] Bhawana Somaaya, while critical of the film's "regular packaging of commercial clichés", commended it for the unique portrayal of the wife, played by Mukerji, who is the sole decision-maker in the family throughout the entire process of surrogacy.[25]

Soundtrack

[edit]| Chori Chori Chupke Chupke | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 2000 |

| Genre | Feature film soundtrack |

| Length | 51:41 |

| Label | Universal Music India |

| Producer | Anu Malik |

The soundtrack for Chori Chori Chupke Chupke was composed by Anu Malik and the lyrics were written by Sameer.[4] It was released in 2000 by Universal Music India.[26] According to the Indian trade website Box Office India, with around two million units sold, the soundtrack became the sixth highest-selling music album of the year.[27]

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke" | Alka Yagnik, Babul Supriyo | 7:35 |

| 2. | "Dekhne Walon Ne" | Udit Narayan, Alka Yagnik | 6:13 |

| 3. | "No. 1 Punjabi" | Sonu Nigam, Jaspinder Narula | 7:12 |

| 4. | "Diwani Diwani" | Anu Malik, Anaida | 5:26 |

| 5. | "Diwana Hai Yeh Man" | Sonu Nigam, Alka Yagnik | 6:58 |

| 6. | "Love You Love You Bolo" | Anu Malik, Alka Yagnik | 5:59 |

| 7. | "Mehandi Mehandi" | Jaspinder Narula | 8:57 |

| 8. | "Dulhan Ghar Aayi" (Version 1) | Jaspinder Narula | 1:41 |

| 9. | "Dulhan Ghar Aayi" (Version 2) | Anu Malik | 1:40 |

| Total length: | 51:41 | ||

Release

[edit]

The film's initial release date of 22 December 2000[28] was delayed when producer Nazim Rizvi was arrested in December and film financier Bharat Shah was arrested in January; both were charged with receiving funding from Chhota Shakeel of the Mumbai underworld and pressuring leading Bollywood actors—specifically, Khan—to appear in the film and for the profits to be shared with Shakeel.[28][29][30][31] Rizvi had reportedly been under telephone surveillance by the Mumbai Police for a number of months.[29] The Central Bureau of Investigation seized the film's prints and delivered them to the court receiver.[29] The negatives were released on 12 February 2001 on a judicial order.[32] In its ruling, the court ordered all profits from the film to go to the Maharashtra state government.[29] Rivzi and Shah were still incarcerated when Chori Chori Chupke Chupke opened to the public on 9 March 2001.[29] The film was released with an opening credit thanking the Special Court, MCOCA, the Crime Branch, the Mumbai Police, and the court receiver, "without whose untiring efforts and good office this picture would never have been made".[30]

The film's release took place amid protests due to its alleged funding by the underworld.[33] Due to the controversy surrounding its delayed release—and the recurrent publicity around it—the film was expected to be a big success, with 325 prints sold before release.[34] The director duo held a special screening of the film two days prior to its release for the senior brass of the Mumbai Police, to fulfill a promise made earlier in order to prove that no objectionable content appeared in the film, as could have been projected.[35]

Certified U (suitable for all age groups) by the Central Board of Film Certification,[36] Chori Chori Chupke Chupke opened to a wide audience and emerged a commercial success and one of the highest-grossing films of 2001.[37][38] Still, despite a strong opening, the film gradually lost public interest; it eventually grossed ₹31 crore (US$3.7 million) against its ₹13 crore (US$1.5 million) budget, with additional $1.4 million earned overseas, leaving its worldwide gross in 2001 at ₹37.51 crore (equivalent to ₹149 crore or US$18 million in 2023).[3] Box Office India concluded the film's final commercial performance with the verdict "semi hit".[37]

Reception

[edit]

Critics praised the uniqueness of the film for dealing with the rarely-touched subject of surrogacy, but disliked the execution. Preity Zinta's performance, in what was seen as an unconventional role, was especially noted by a number of critics, with high praise for her portrayal of the gradual change her character goes through over the course of the story.[39][40] Film critic Sukanya Verma, who was left with "mixed emotions" after seeing the film, noted Zinta's role as "the meatiest part of all", finding her transformation throughout the film "amazingly believable".[41] Padmaraj Nair of Screen called Zinta the film's "real scene-stealer" for having delivered "a stunning performance".[42] Vinayak Chakravorty of Hindustan Times hailed Zinta's "admirable zest" as the "trumpcard of the film".[43] Dinesh Raheja of India Today credited Zinta with giving the film "its electric charge".[44] Likewise, Nikhat Kazmi of The Times of India noted Zinta for keeping "the adrenalin gushing" and wrote of "riveting moments" where she "shows flashes of a fine performance".[45] Ziya Us Salam of The Hindu, though similarly fond of Zinta for putting "life into her character of Madhubala", found the actress less convincing in "mouthing the inanities used by the women of the street".[46] M. Shamim, writing for the same publication, believed Zinta had "put her body and soul into the streetwalker's flaming-red dress".[15]

The duo of Salman Khan and Rani Mukerji faced some criticism from Sukanya Verma, who lamented their underdeveloped roles. She considered Mukerji to be "handicapped with a role that doesn't give her much scope besides weeping and sobbing" and stated that Khan's performance lacked substance.[41] Raheja described Khan as "overtly subdued" as opposed to his recent comic roles, but wrote of Mukerji, "The emotions that drive Rani Mukherji's character are not given either a layered detailing or an adequate exposition so she comes across as pale as the pastel-coloured dresses she favours".[44] Chakravorty similarly noted Khan for playing against type.[43] Kazmi similarly disliked their characters in contrast to Zinta's: "From a street-walker to sensitive young girl and then a jealous lover - stray vignettes of flesh and blood form from Preity which come as a respite in a terrain dominated by an ever-say-cheese and forever understanding Rani and an unruffled, mumbling Salman who plays the perfect gentleman with the zeal of a zombie."[45] Padmaraj Nair, however, praised the actors in addition to Zinta, noting Khan for his "understated" performance, and arguing that Mukerji is "at her best".[42]

Chori Chori Chupke Chupke was reviewed positively by a number of critics. Taran Adarsh from the entertainment portal Bollywood Hungama was positive of the film, concluding it "lives up to the towering expectations thanks to the solid drama".[47] Several reviewers appreciated the film for its portrayal of the big family and its overall positive atmosphere, including Kazmi, who found it to be a "modern ode to the ancient Indian family" and admired its "overwhelming feel-goodness".[29][45] Likewise, Us Salam noted the film's "loads of good music, beautiful locales, sweet smiles and lovely feel", and Shamim shared similar sentiments, appreciating the directors for not allowing "any moral issue to cloud the narrative" and filling "the screen with mesmerising charm and beauty of the lifestyle of a well-knit family".[15]

Less positive views were expressed in relation to the film's stereotypical approach and poor execution of the story. Verma found the presentation of the story to be "absurd".[41] Nair was ambivalent towards the film in this regard: "On the one hand, the film stands by family values and desi culture while, on the other, it goes in for cheap gimmicks like hiring a cabaret dancer as a solution for bearing a child just to lure the front benchers and the masses". Still, he ultimately noted an "engrossing" second half and commended the directors for having "done their best to bring a fair amount of conviction while putting it across on the screen".[42]

Vinayak Chakravorty, who gave the film a three-star rating, noted its resemblance to Doosri Dulhan and criticised it for occasionally coming across as "a veritable rerun of the stereotypes". Raheja was critical of the film's lack of subtlety but believed the directors are "masters of pace and don't allow your attention to wander".[44] Suman Tarafdar of Filmfare was particularly critical of the film, calling it "saccarine" and "a film for anyone gullible enough to believe in fairy lands", and noting that Zinta gave "the only slightly noteworthy performance".[48]

Accolades

[edit]Khan was named the Most Sensational Actor at the Bollywood Movie Awards.[49] At the 47th Filmfare Awards, Zinta was nominated in the Best Supporting Actress category, the only nomination for the film.[50]

Legacy

[edit]Chori Chori Chupke Chupke has often been associated with surrogacy in Indian popular culture.[17] It has been screened at a number of events since its release. In 2002, it was one of 30 films screened at a three-month-long Bollywood event organised by the Swiss Government in Zürich.[51] It was later screened at the 2005 Independent South Asian Film Festival and the 2012 Fiji Film Festival.[52][53]

Zinta's role has been noted as one of her notable works. In a column about Zinta, published in an August 2001 issue of Screen magazine, Roshmila Bhattacharya asserted, "If Chori Chori Chupke Chupke found a following in conventional circles, it's thanks to Preity’s handling of yet another 'brave' role".[39] In a 2003 column for Sify about the portrayal of sex-workers in Hindi films, Subhash K. Jha wrote of Zinta that in spite of being "uncomfortable about using all the foul language ... Once she entered the zone of the rented womb Preity had a ball. This remains her best performance yet".[54] Published in the same year, a column analysing Zinta's career by Stardust found her to be "manifested [her]self most prominently ... in [the film]", adding, "Here was Preity essaying a character with tremendous scope for performance, but the scenes in which she excelled was when she did her bubbly act in the initial stages of the film".[55]

References

[edit]- ^ "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke (2001)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b Joseph, Manu (25 December 2000). "Scenes of the Mafia". Outlook. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke Cast & Crew". Bollywood Hungama. 9 March 2001. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke Cast". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b Mittal, Madhur (3 October 1999). "Abbas–Mastan's masti". The Tribune. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Renuka, Methil (27 November 2000). "Action replay". India Today. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Under suspicion". Bollywood Hungama. December 2000. Archived from the original on 24 January 2001. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Ashraf, Syed Firdaus (9 January 2003). "Bharat Shah case: Preity Zinta sticks to her stand". Rediff.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Why Preity refused to play a prostitute..." Sify. IndiaFM News Bureau. 29 April 2005. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Puri, Amrish; Sabharwal, Jyoti (24 May 2006). The Act of Life. Stellar Publishers. p. 335. ISBN 978-81-902247-4-1.

- ^ Mahmood, Abdulla (16 May 2008). "Bollywood hot spots over the years". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Param, Arunachalam (2019). BollySwar: 2001–2010. Mavrix Infotech Private Limited. p. 20. ISBN 978-81-938482-0-3.

- ^ Shikha, Sharma (2020). "Raising awareness on surrogacy through films". Mass Communicator: International Journal of Communication Studies. 14 (2). ISSN 0973-9688.

- ^ a b c Shamim, M. (11 March 2001). "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke — and how!". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Bharadwaj, Aditya (2016). Conceptions: Infertility and Procreative Technologies in India. Berghahn Books. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-78533-231-9.

- ^ a b Majumdar, Anindita (2018). Surrogacy. Oxford University Press. pp. 19–23. ISBN 978-0-19-909654-1.

- ^ Grey, Daniel (2017). Davis, Gayle; Loughran, Tracey (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Infertility in History: Approaches, Contexts and Perspectives. Springer. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-137-52080-7.

- ^ Rustam, Chhupa (25 March 2001). "Double trouble all the way". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 13 March 2002. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b Krämer, Lucia (2017). "Adaptation in Bollywood". In Leitch, Thomas (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-19-933100-0.

- ^ Majumdar, Anindita (2017). Transnational Commercial Surrogacy and the (Un)Making of Kin in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-19-909142-3.

- ^ Chopra, Anupama (2 April 2001). "The courtesan club". India Today. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Derne, Steve D. (2008). Globalization on the Ground: New Media and the Transformation of Culture, Class, and Gender in India. SAGE Publications India. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-81-321-0038-6.

- ^ Banaji, S. (2006). Reading 'Bollywood': The Young Audience and Hindi Films. Springer. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-230-50120-1.

- ^ Somaaya, Bhawana (2004). Cinema: Images & Issues. Rupa & Company. p. 34. ISBN 9788129103703.

- ^ a b "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke (Soundtrack from the Motion Picture)". iTunes. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Music Hits 2000–2009 (Figures in Units)". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ^ a b Rediff Entertainment Bureau (13 December 2000). "Showbuzz! Chori Chori Chupke Chupke producer arrested". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Harding, Luke (14 March 2001). "Dirty money cleans up for Bollywood blockbuster". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b Rajadhyaksha, Ashish (2014). "The Guilty Secret: The Latter Career of the Bollywood's Illegitimacy" (PDF). Asia Research Institute. 230. Bangalore, India.

- ^ "Diamond daddy". India Today. 31 December 2001. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Judge allows release of 'Chori Chori Chupke Chupke'". Rediff.com. 12 February 2001. Archived from the original on 28 December 2004. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ ""Chori Chori" opens amid protests". The Tribune. 9 March 2001. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Debashis (6 March 2001). "Chupke Crores For Chori Chori". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Nahta, Komal (8 March 2001). "Special screening of CCCC for top cops". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ IndiaFM News Bureau (20 December 2000). "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke given U certificate by the Censor". Bollywood Hungama. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Top Hits 2001". Box Office India. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Box Office Collection India 2001". Bollywood Hungama. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, Roshmila (3 August 2001). "Preity Zinta Different Strokes". Screen. Archived from the original on 31 October 2001. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ Kothari, Jitendra (2001). "Preity Zinta: Taking Charge". India Today. TNT Movies. Archived from the original on 26 June 2001. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Verma, Sukanya (9 March 2001). "Preity Trite". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2008.

- ^ a b c Nair, Padmaraj (23 March 2001). "Desi version of Surrogate Mother". Screen. Archived from the original on 3 January 2003. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Chakravorty, Vinayak (9 March 2001). "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2001. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Raheja, Dinesh (2001). "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke — A Preity Show". India Today. Archived from the original on 9 April 2001. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Kazmi, Nikhat (9 March 2001). "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke". The Times of India. The Times Group. Archived from the original on 9 November 2001. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Us Salam, Ziya (16 March 2001). "Film review: Chori Chori Chupke Chupke". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Adarsh, Taran (8 March 2001). "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke Movie Review". Bollywood Hungama. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Tarafdar, Suman (2001). "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke". Filmfare. The Times Group. Indiatimes Movies. Archived from the original on 23 October 2001. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Winners of Bollywood Movie Awards". Bollywood Movie Awards. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ "Preity Zinta: Awards & nominations". Bollywood Hungama. Archived from the original on 26 May 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ Times News Network (23 May 2002). "Bollywood bug bites Switzerland". The Times of India. The Times Group. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "ISAFF 2005 – Festival Launch Party". Tasveer.org. Independent South Asian Film Festival. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Stolz, Ellen (5 October 2012). "FNU Film Festival On". Fiji Sun. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ K. Jha, Subhash (30 October 2003). "Playing the streetwalker". Sify. Archived from the original on 7 March 2004. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Not just Pretty!". Stardust. August 2003. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Raval, Sheela; Chopra, Anupama (22 January 2001). "Bollywood body blow". India Today. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Raval, Sheela (2015). Godfathers of Crime: Face to Face with India's Most Wanted. Hachette India. pp. 174–176. ISBN 978-93-5009-977-3.

- "The Bharat Shah case". Rediff.com. 2003. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

External links

[edit]- Chori Chori Chupke Chupke at IMDb

- Chori Chori Chupke Chupke at Bollywood Hungama (archived)

Chori Chori Chupke Chupke

View on GrokipediaSynopsis

Plot Summary

Raj Malhotra, a wealthy industrialist, marries Priya Bhatia, the daughter of a rival businessman, in a union initially opposed by her father but ultimately accepted after reconciliation.[2] Soon after their wedding on an unspecified date in the film's timeline, the couple discovers that Priya cannot conceive due to complications from a childhood accident that rendered her infertile.[2] To conceal this from their families and preserve marital harmony while fulfilling their longing for a child, Raj arranges for surrogate motherhood by contracting Madhuri "Madhu" Vyas, a compassionate prostitute, for one million rupees; Raj impregnates her during a single encounter to ensure conception.[11][12] As Madhu's pregnancy advances, she develops deep romantic feelings for Raj, complicating the arrangement.[11] To deflect family inquiries about the unexplained pregnancy, Raj presents Madhu as his second wife, invoking cultural allowances for polygamy to legitimize her presence and impending childbirth.[13] Madhu endures harassment from Raj's unscrupulous business associate, who demands sexual favors, prompting her to consider departing, though Raj persuades her to remain until delivery.[12] The families eventually learn the surrogacy truth, yet accommodate Madhu's role.[14] Upon giving birth to a son in a hospital scene, Madhu bonds intensely with the infant and resists surrendering him to Priya, sparking emotional conflict and negotiations.[11] Raj convinces Madhu to relinquish the child by appealing to her selflessness and circumstances, after which she departs; Raj and Priya name the boy and relocate temporarily to Switzerland with Madhu under the pretense of family unity to evade further scrutiny.[13][15]Production

Development

The director duo Abbas and Mustan Burmawalla conceived Chori Chori Chupke Chupke as a departure from their typical thriller genre, focusing on a romantic drama that addressed surrogacy—a rarely explored topic in Indian cinema at the time. The story, centered on a newlywed couple navigating infertility and turning to a surrogate mother, was originally penned by screenwriter Neeraj Vora, who crafted the foundational narrative around themes of marital bonds, societal stigma, and unconventional parenthood.[16] This premise marked an ambitious attempt to blend emotional family dynamics with dramatic tension, drawing on real-world taboos while aiming for commercial appeal through star-driven casting.[4] Javed Siddiqui expanded Vora's story into the full screenplay and dialogues, emphasizing character-driven conflicts such as the surrogate's personal sacrifices and the couple's ethical dilemmas, which were intended to provoke discussion on family ethics without overt preachiness.[16] Producer Nazim Hassan Rizvi, previously involved in lower-budget films, financed the project through his banner Emaar Films Combines, viewing it as a high-stakes venture with a budget reportedly exceeding standard mid-tier productions of the era. Rizvi's involvement brought logistical support for pre-production planning, including location scouting in India and abroad, but the film's development phase also set the stage for later scrutiny over funding sources, as Rizvi was a novice in major league Bollywood projects.[17][18] Early development emphasized sensitivity to cultural norms, with the script undergoing revisions to balance bold elements like premarital pregnancy and sex work with redemptive arcs, ensuring broader audience acceptability. Anu Malik was onboarded early for the musical score, aligning compositions with the film's emotional core to enhance marketability. This phase positioned the film as a potential trendsetter in depicting modern relational challenges, though its execution later drew mixed assessments on depth versus melodrama.[16]Casting

The lead role of Raj Malhotra, a wealthy heir navigating infertility and surrogacy, was portrayed by Salman Khan. Rani Mukerji was cast as his wife Priya Malhotra, who faces health issues preventing conception, while Preity Zinta played Madhubala "Madhu" Singh, the surrogate mother whose involvement complicates family dynamics. Supporting roles included Amrish Puri as Raj's father Kailashnath Malhotra, Dalip Tahil as uncle Ranjit Malhotra, and Farida Jalal as mother Asha Malhotra.[16][19] The casting process drew controversy due to producer Nazim Rizvi's alleged connections to the Mumbai underworld. Rizvi, arrested in December 2000 just before the film's intended release, was charged with links to gangster Chhota Shakeel, who reportedly pressured Salman Khan to participate in the project. This led to investigations by Mumbai police and the CBI, with film prints seized and the release postponed until March 2001 after clearances. Preity Zinta, one of the few witnesses who did not turn hostile, testified about receiving extortion threats related to the production. Despite allegations of coerced involvement, no formal charges against the actors resulted from the probe, and the film proceeded with its selected ensemble.[20][21]Filming

Principal photography for Chori Chori Chupke Chupke took place primarily on location in Switzerland, including Lucerne and areas around Lake Lungern.[22] Several song sequences, such as the title track, were filmed amidst the Swiss landscapes to capture scenic backdrops for the romantic elements of the story.[23] Additional shooting occurred in Mahabaleshwar, a hill station in India, for interior and narrative-driven scenes requiring Indian locales.[24] The production schedule aligned with the film's planned December 2000 release, necessitating efficient location work abroad before post-production delays pushed the premiere to March 2001.[25] No major disruptions were reported during the shoots, though the film's overall timeline was affected by external investigations into its financing post-completion.[26]Post-production and Delays

Following the completion of principal photography, post-production for Chori Chori Chupke Chupke proceeded, including editing, sound mixing, and visual effects, positioning the film for an initial release date of 22 December 2000.[27] However, the process was overshadowed by legal investigations into the film's financing, leading to significant delays in certification and distribution. Prints of the film were seized by authorities, preventing submission to the Central Board of Film Certification and halting any immediate theatrical rollout.[28] The primary cause of the delays stemmed from the December 2000 arrest of producer Nazim Rizvi, who was implicated in a broader probe into Bollywood's alleged ties to organized crime, alongside financier Bharat Shah, a diamond merchant accused of channeling underworld funds—reportedly from figures like Chhota Shakeel—into the production.[6] [29] Rizvi's detention disrupted oversight of final deliverables, while Shah's involvement triggered a Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) inquiry that scrutinized the film's budget and revenue streams, including pre-sale deals worth approximately ₹150 million for distribution and audio-video rights.[30] These events, part of a high-profile crackdown on extortion and money laundering in the industry, postponed the release by several months, with the film ultimately premiering on 9 March 2001 after court interventions allowed limited proceedings under a receiver.[27] [29] Actor Preity Zinta, who portrayed a lead role, later testified in the related trial, describing the experience as intimidating amid threats and abuse from defense counsel, which underscored the production's entanglement in criminal proceedings rather than routine post-production hurdles.[27] Despite the setbacks, the film's technical post-production remained intact, enabling a successful box-office run upon clearance, though the episode highlighted vulnerabilities in Bollywood's opaque financing practices during the era.[29]Cast

Principal Performers

Salman Khan starred as Raj Malhotra, a affluent industrialist who marries Priya but discovers his infertility, leading to the surrogacy arrangement central to the plot.[16] His portrayal was described as controlled, classy, and mature, diverging from his typical high-energy action roles and earning praise for emotional restraint in handling family dilemmas.[31] Rani Mukerji enacted Priya Malhotra, Raj's supportive wife unable to conceive naturally, who agrees to the surrogate motherhood plan while grappling with jealousy and attachment.[16] Critics noted her effective delivery of emotional scenes, with equal screen time and narrative weight shared alongside co-lead Zinta, contributing to the film's exploration of marital strain.[31] Preity Zinta portrayed Madhubala Singh, nicknamed Madhu, a financially desperate woman from a rural background who becomes the surrogate and develops unexpected bonds with the child and family.[16] Her performance, blending vivacity with vulnerability in depicting a sex worker's redemption arc, was highlighted for stealing scenes and adding dynamism to the love triangle dynamics.[32][31] The ensemble's spontaneous chemistry was credited with offsetting script inconsistencies, though some reviews critiqued the overall handling of sensitive character motivations.[33]Supporting Roles

Amrish Puri played Kailashnath Malhotra, the authoritative father of the protagonist Raj, whose traditional values influence key family decisions in the narrative.[34][19] Dalip Tahil portrayed Ranjit Malhotra, Priya's father, contributing to the portrayal of inter-family tensions surrounding infertility and surrogacy arrangements.[35] Farida Jalal appeared as Asha Malhotra, Raj's mother, offering emotional support and maternal perspective amid the central couple's marital challenges.[35] Johnny Lever provided comic relief in a secondary role, injecting humor into otherwise dramatic sequences typical of his Bollywood supporting performances.[36] Prem Chopra featured in an antagonistic supporting capacity, adding conflict to the plot's familial and social dynamics.[36]| Actor | Character | Role Description |

|---|---|---|

| Amrish Puri | Kailashnath Malhotra | Raj's stern father enforcing family norms |

| Dalip Tahil | Ranjit Malhotra | Priya's father involved in surrogacy plot |

| Farida Jalal | Asha Malhotra | Raj's nurturing mother |

| Johnny Lever | (Comic supporting) | Provider of levity and side gags |

| Prem Chopra | (Antagonistic) | Source of external conflict |

Soundtrack

Composition

The soundtrack's music was composed by Anu Malik, with all lyrics penned by Sameer.[37] [38] The compositions blend melodic romantic tunes with festive and folk-influenced tracks, including Punjabi rhythms in "No. 1 Punjabi" and extended wedding sequences in "Mehandi Mehandi" and "Dulhan Ghar Aayi," aligning with the film's narrative of marriage and surrogacy.[38] [37] The album features eight tracks, primarily sung by Alka Yagnik across multiple songs, alongside contributions from Udit Narayan, Sonu Nigam, Jaspinder Narula, Babul Supriyo, Anaida, and Anu Malik himself in one duet.[38] [39]| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chori Chori Chupke Chupke | Alka Yagnik, Babul Supriyo | 7:35 |

| 2 | Dekhne Walon Ne | Alka Yagnik, Udit Narayan | 6:14 |

| 3 | No. 1 Punjabi | Sonu Nigam, Jaspinder Narula | 6:00 |

| 4 | Diwani Diwani | Alka Yagnik, Anaida | 7:00 |

| 5 | Diwana Hai Ye Man | Alka Yagnik, Sonu Nigam | 5:30 |

| 6 | Love You Love You Bolo | Alka Yagnik, Anu Malik | 5:59 |

| 7 | Mehandi Mehandi | Jaspinder Narula | 8:57 |

| 8 | Dulhan Ghar Aayi | Jaspinder Narula | 4:30 |

Commercial Performance

The soundtrack sold 2,000,000 units worldwide.[40] This figure positioned it as a major commercial success in the Indian music market, where physical formats like cassettes dominated sales at the time.[41] Composed by Anu Malik with lyrics by Sameer, the album's popularity was driven by hit tracks such as "Chori Chori Chupke Chupke" and "Dekhne Walon Ne", which contributed to its strong performance amid competition from other Bollywood releases in 2000.[40] No official certifications from bodies like the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry were reported for the album.Themes

Surrogacy and Family Dynamics

The film centers on the surrogacy arrangement entered by protagonists Raj Malhotra (Salman Khan) and Madhuri "Madhu" (Rani Mukerji), who face infertility after Madhu suffers complications from a car accident that prevent her from carrying a pregnancy.[11] Unable to conceive naturally and rejecting adoption or IVF to maintain secrecy, the couple recruits Priya (Preity Zinta), a courtesan, as a traditional surrogate mother who conceives via natural insemination with Raj, making her the biological mother of the child.[42] This decision stems from intense familial pressure, particularly from Raj's grandfather, who insists on a biological heir to continue the family lineage, highlighting patriarchal expectations in Indian joint family structures.[43] The surrogacy process disrupts family dynamics, fostering unintended emotional attachments and conflicts. Priya's growing affection for Raj introduces jealousy and insecurity in Madhu, straining the marital bond despite their mutual commitment, while the secrecy imposed to shield the arrangement from extended family amplifies deception and guilt within the household.[44] The narrative underscores the psychological toll of infertility on the couple, portraying Madhu's despair and Raj's sense of inadequacy under societal norms that equate manhood with fatherhood.[45] Upon the child's birth on an unspecified date in the film's timeline, Priya reluctantly relinquishes custody after emotional turmoil, enabling Raj and Madhu to integrate the infant into their family under the pretense of natural birth, thus restoring surface-level harmony but revealing underlying tensions in non-traditional reproduction.[11] Critics have noted the film's emphasis on the commissioning couple's trauma over the surrogate's agency, reflecting 2001-era Bollywood's limited engagement with surrogacy's ethical complexities, such as exploitation risks in commercial arrangements.[9] This portrayal prioritizes familial continuity and resolution through melodrama rather than realistic exploration of legal or medical surrogacy protocols prevalent by the early 2000s in India.[46]Gender Roles and Social Norms

The film Chori Chori Chupke Chupke depicts gender roles within a traditional Indian familial framework, where women's primary societal value is tied to motherhood and reproductive capacity. The protagonist Madhu, played by Rani Mukerji, faces intense stigma and emotional distress due to her infertility, reflecting broader cultural norms that place the burden of progeny—particularly male heirs—squarely on women, rendering childless wives inadequate in the eyes of extended family and society.[47][43] This portrayal underscores the patriarchal expectation that a woman's fulfillment derives from domesticity and childbearing, with infertility portrayed as a personal failing that disrupts marital harmony and invites communal judgment, as evidenced by the couple's secretive surrogacy arrangement to evade social ostracism.[48] Social norms around surrogacy in the film further entrench these roles, presenting the surrogate Priya (Preity Zinta) as initially embodying a "fallen" or economically desperate femininity, which she redeems through maternal sacrifice and integration into the normative family structure. Priya's arc—from a woman coerced into surrogacy due to financial hardship to one who relinquishes the child while gaining moral redemption—reinforces stereotypes of surrogate mothers as transient figures whose agency is subordinated to the commissioning couple's needs, challenging contractual autonomy while upholding the ideal of selfless, biologically driven motherhood.[9][45] This dynamic highlights causal pressures in Indian society, where economic vulnerabilities disproportionately affect women, funneling them into roles that perpetuate gender hierarchies rather than dismantle them. The narrative's resolution exposes inconsistencies in social norms, forgiving the male lead Raj's (Salman Khan) infidelity and emotional entanglement with Priya in favor of patriarchal family preservation, while women's deviations from prescribed roles invite harsher scrutiny. Such elements critique surface-level taboos like surrogacy but ultimately affirm conservative gender binaries, with women's emotional labor—enduring betrayal, stigma, and sacrifice—serving to restore male-centered domestic order, a pattern critiqued for its misogynistic undertones in reinforcing familial obsession over individual autonomy.[48][49][50]Controversies

Underworld Funding and Investigations

The production of Chori Chori Chupke Chupke came under scrutiny from Mumbai Police in late 2000 amid allegations that its financing involved funds from the underworld syndicate led by Chhota Shakeel, an associate of Dawood Ibrahim.[29][51] Producer Nazim Rizvi, who had been under surveillance for months, was arrested on December 13, 2000, for allegedly channeling mafia money into the film, prompting police to seize the movie's negatives and delay its release.[52][53] Rizvi's financier, diamond merchant Bharat Shah, was arrested on January 8, 2001, after investigations revealed his company, Mega Bollywood, had provided approximately Rs 12.7 crore toward the project's budget, with claims of underworld involvement in the funding pipeline.[26][54] Investigations by the Mumbai Police's Crime Branch, later involving the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), centered on wiretaps and informant testimony linking Rizvi and Shah to Shakeel's network, including assertions that the gangster had invested around Rs 15 crore to launch Rizvi's debut production.[55][56] Mumbai Police Commissioner M. N. Singh publicly identified Chori Chori Chupke Chupke as one of a handful of films suspected of underworld financing during this period, noting patterns of coercion where actors like Salman Khan were reportedly pressured to participate.[57] In March 2001, a special court granted conditional release for the film's distribution prints after legal challenges from the accused, allowing a limited theatrical rollout despite ongoing probes.[58] Rizvi and an associate received six-year prison sentences in 2001 from a special anti-underworld court for conspiring with mafia elements to fund and protect the production, though appeals and bail processes extended their legal battles.[55][59] Shah faced separate charges under the Maharashtra Control of Organized Crime Act (MCOCA), leading to his conviction in 2003 for facilitating tainted funds, with the case highlighting systemic vulnerabilities in Bollywood's opaque financing practices.[26] These probes, while confirming some illicit ties, drew criticism for relying heavily on intercepted communications and unverified informant claims, underscoring challenges in prosecuting cross-border mafia operations.[60]Social and Political Backlash

The release of Chori Chori Chupke Chupke on March 9, 2001, encountered opposition from right-wing Hindu activist groups, who protested the film's screening amid revelations of its partial financing by individuals linked to organized crime. Bajrang Dal, a youth wing affiliated with the Vishva Hindu Parishad, initially announced plans to block the film's nationwide release, citing concerns over the moral implications of underworld involvement in mainstream cinema.[61] This decision was withdrawn on the day of release following negotiations, allowing screenings to proceed amid heavy advance bookings in Mumbai.[62] Broader political discourse highlighted apprehensions about Bollywood's entanglement with criminal elements, with right-wing activists framing the film as emblematic of cultural decay enabled by illicit funds. Protests in Mumbai drew attention to demands for stricter oversight of film financing to preserve societal values, though no formal bans were imposed by government authorities.[29] The controversy amplified calls from Hindu nationalist factions for ethical reforms in the industry, positioning the film as a flashpoint in debates over art's vulnerability to external corruption. Socially, the film's depiction of surrogacy—portraying a childless couple hiring a former sex worker as a surrogate—elicited criticism for oversimplifying ethical complexities and potentially endorsing commodification of motherhood in a conservative context. Contemporary reviews noted flak for the plot's reliance on sentimental tropes that glamorized a taboo reproductive practice without addressing exploitation risks, fueling unease among audiences wary of Western-influenced family norms.[63] This thematic backlash, though overshadowed by funding scandals, contributed to early public skepticism toward commercial surrogacy in India, predating later regulatory debates.[9]Threats to Cast and Crew

During the 2001 production of Chori Chori Chupke Chupke, lead actress Preity Zinta received several extortion calls from callers identifying as associates of underworld figure Chhota Shakeel, demanding Rs 50 lakh (about $110,000 USD).[64] These threats occurred amid the film's alleged underworld financing, which drew police scrutiny and arrests.[7] Zinta confided in her secretary, Pankaj Kharbanda—who also managed Sanjay Dutt's affairs—and reported the incidents, later testifying in the Bharat Shah case on January 9, 2003, where she affirmed the calls happened during filming.[65][66] The set environment was marked by widespread paranoia among cast and crew, exacerbated by the January 2000 shooting of producer Rakesh Roshan by gangsters, which fueled fears of similar reprisals tied to Bollywood's underworld entanglements.[7] Zinta's testimony stood out as other actors, including Sanjay Dutt and Shah Rukh Khan—who had peripheral links to the case—denied or retracted claims of threats, turning hostile in court.[67] She later described the experience as "scary," noting how courtroom abuse during cross-examination intensified the ordeal, yet she persisted despite industry pressure to recant.[27] No verified reports detail direct threats to co-stars Salman Khan or Rani Mukerji specifically from this production, though Khan has faced broader underworld intimidation, including coercion allegations to participate in the film.[68] Crew members, such as producer Nazim Rizvi's associates, encountered indirect risks via the funding probe but lacked documented personal threats. Zinta's case highlighted the perils of underworld infiltration in Bollywood, with her refusal to back down contrasting the silence from peers.[69]Release

Theatrical Premiere

was released theatrically across India on 9 March 2001.[70][1][71] The film premiered on 295 screens, reflecting a broad distribution strategy typical for major Hindi releases of the era.[72] Its opening day performance set a record, grossing ₹1.14 crore nett, the highest first-day collection achieved by any Indian film to date.[72] This strong debut was driven by the star power of Salman Khan, alongside anticipation for the surrogacy-themed narrative directed by Abbas–Mustan.[72]Marketing and Distribution

The film was distributed in India by Eros International and released theatrically on March 9, 2001, across 295 screens.[72] Eros Worldwide handled international distribution from 2001 to 2005, contributing to its overseas earnings.[73] Later home video and video-on-demand rights were acquired by entities including Amazon Prime Video in India and NH Studioz globally starting in 2010.[73] Marketing efforts focused on the star power of Salman Khan, Rani Mukerji, and Preity Zinta, positioning the film as a romantic drama exploring family themes. The soundtrack, composed by Anu Malik, served as a key promotional tool, with audio releases and launch events featuring cast appearances to build anticipation.[74] However, pre-release promotions were constrained by legal scrutiny over production funding, delaying the original December 22, 2000, launch date amid investigations into underworld ties.[29] Clearance by authorities in early 2001 enabled final distribution approvals, allowing standard advertising via posters and trailers emphasizing the ensemble cast.[58]Reception

Box Office Results

Chori Chori Chupke Chupke was produced on a budget of ₹13 crore.[72] The film achieved a worldwide gross of ₹37.51 crore, comprising ₹31 crore from the Indian market and US$1.4 million from overseas territories.[72] Its Indian nett earnings totaled ₹18.35 crore.[14] Box Office India classified the film as a hit, reflecting its strong performance relative to production costs and distributor shares.[72] The movie ranked among the higher-grossing releases of 2001, benefiting from Salman Khan's star draw and the film's thematic appeal during its theatrical run starting March 9, 2001.[75] Overseas earnings were driven primarily by diaspora audiences in regions like the United States, United Kingdom, and Gulf countries, where it grossed approximately US$406,000 in the US alone.[72]| Metric | Amount |

|---|---|

| Budget | ₹13 crore |

| India Nett Gross | ₹18.35 crore |

| India Gross | ₹31 crore |

| Overseas Gross | US$1.4 million |

| Worldwide Gross | ₹37.51 crore |