Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chromatic polynomial

View on Wikipedia

The chromatic polynomial is a graph polynomial studied in algebraic graph theory, a branch of mathematics. It counts the number of graph colorings as a function of the number of colors and was originally defined by George David Birkhoff to study the four color problem. It was generalised to the Tutte polynomial by Hassler Whitney and W. T. Tutte, linking it to the Potts model of statistical physics.

History

[edit]George David Birkhoff introduced the chromatic polynomial in 1912, defining it only for planar graphs, in an attempt to prove the four color theorem. If denotes the number of proper colorings of G with k colors then one could establish the four color theorem by showing for all planar graphs G. In this way he hoped to apply the powerful tools of analysis and algebra for studying the roots of polynomials to the combinatorial coloring problem.

Hassler Whitney generalised Birkhoff’s polynomial from the planar case to general graphs in 1932. In 1968, Ronald C. Read asked which polynomials are the chromatic polynomials of some graph, a question that remains open, and introduced the concept of chromatically equivalent graphs.[1] Today, chromatic polynomials are one of the central objects of algebraic graph theory.[2]

Definition

[edit]

For a graph G, counts the number of its (proper) vertex k-colorings. Other commonly used notations include , , or . There is a unique polynomial which evaluated at any integer k ≥ 0 coincides with ; it is called the chromatic polynomial of G.

For example, to color the path graph on 3 vertices with k colors, one may choose any of the k colors for the first vertex, any of the remaining colors for the second vertex, and lastly for the third vertex, any of the colors that are different from the second vertex's choice. Therefore, is the number of k-colorings of . For a variable x (not necessarily integer), we thus have . (Colorings which differ only by permuting colors or by automorphisms of G are still counted as different.)

Deletion–contraction

[edit]The fact that the number of k-colorings is a polynomial in k follows from a recurrence relation called the deletion–contraction recurrence or Fundamental Reduction Theorem.[3] It is based on edge contraction: for a pair of vertices and the graph is obtained by merging the two vertices and removing any edges between them. If and are adjacent in G, let denote the graph obtained by removing the edge . Then the numbers of k-colorings of these graphs satisfy:

Equivalently, if and are not adjacent in G and is the graph with the edge added, then

This follows from the observation that every k-coloring of G either gives different colors to and , or the same colors. In the first case this gives a (proper) k-coloring of , while in the second case it gives a coloring of . Conversely, every k-coloring of G can be uniquely obtained from a k-coloring of or (if and are not adjacent in G).

The chromatic polynomial can hence be recursively defined as

- for the edgeless graph on n vertices, and

- for a graph G with an edge (arbitrarily chosen).

Since the number of k-colorings of the edgeless graph is indeed , it follows by induction on the number of edges that for all G, the polynomial coincides with the number of k-colorings at every integer point x = k. In particular, the chromatic polynomial is the unique interpolating polynomial of degree at most n through the points

Tutte’s curiosity about which other graph invariants satisfied such recurrences led him to discover a bivariate generalization of the chromatic polynomial, the Tutte polynomial .

Examples

[edit]| Triangle | |

| Complete graph | |

| Edgeless graph | |

| Path graph | |

| Any tree on n vertices | |

| Cycle | |

| Petersen graph |

Properties

[edit]For fixed G on n vertices, the chromatic polynomial is a monic polynomial of degree exactly n, with integer coefficients.

The chromatic polynomial includes at least as much information about the colorability of G as does the chromatic number. Indeed, the chromatic number is the smallest positive integer that is not a zero of the chromatic polynomial,

The polynomial evaluated at , that is , yields times the number of acyclic orientations of G.[4]

The derivative evaluated at 1, equals the chromatic invariant up to sign.

If G has n vertices and c components , then

- The coefficients of are zeros.

- The coefficients of are all non-zero and alternate in signs.

- The coefficient of is 1 (the polynomial is monic).

- The coefficient of is

We prove this via induction on the number of edges on a simple graph G with vertices and edges. When , G is an empty graph. Hence per definition . So the coefficient of is , which implies the statement is true for an empty graph. When , as in G has just a single edge, . Thus coefficient of is . So the statement holds for k = 1. Using strong induction assume the statement is true for . Let G have edges. By the contraction-deletion principle,

Let and

Hence .

Since is obtained from G by removal of just one edge e, , so and thus the statement is true for k.

- The coefficient of is , where is the number of triangles (3-cycle subgraphs) in .

- The coefficient of is times the number of acyclic orientations that have a unique sink, at a specified, arbitrarily chosen vertex.[5]

- The absolute values of coefficients of every chromatic polynomial form a log-concave sequence.[6]

The last property is generalized by the fact that if G is a k-clique-sum of and (i.e., a graph obtained by gluing the two at a clique on k vertices, isomorphic to the complete graph ), then

A graph G with n vertices is a tree if and only if

Chromatic equivalence

[edit]

Two graphs are said to be chromatically equivalent if they have the same chromatic polynomial. Isomorphic graphs have the same chromatic polynomial, but non-isomorphic graphs can be chromatically equivalent. For example, all trees on n vertices have the same chromatic polynomial. In particular, is the chromatic polynomial of both the claw graph and the path graph on 4 vertices.

A graph is chromatically unique if it is determined by its chromatic polynomial, up to isomorphism. In other words, G is chromatically unique, then would imply that G and H are isomorphic. All cycle graphs are chromatically unique.[7]

Chromatic roots

[edit]A root (or zero) of a chromatic polynomial, called a “chromatic root”, is a value x where . Chromatic roots have been very well studied, in fact, Birkhoff’s original motivation for defining the chromatic polynomial was to show that for planar graphs, for x ≥ 4. This would have established the four color theorem.

No graph can be 0-colored, so 0 is always a chromatic root. Only edgeless graphs can be 1-colored, so 1 is a chromatic root of every graph with at least one edge. On the other hand, except for these two points, no graph can have a chromatic root at a real number smaller than or equal to 32/27.[8] A result of Tutte connects the golden ratio with the study of chromatic roots, showing that chromatic roots exist very close to : If is a planar triangulation of a sphere then

While the real line thus has large parts that contain no chromatic roots for any graph, every point in the complex plane is arbitrarily close to a chromatic root in the sense that there exists an infinite family of graphs whose chromatic roots are dense in the complex plane.[9]

Colorings using all colors

[edit]For a graph G on n vertices, let denote the number of colorings using exactly k colors up to renaming colors (so colorings that can be obtained from one another by permuting colors are counted as one; colorings obtained by automorphisms of G are still counted separately). In other words, counts the number of partitions of the vertex set into k (non-empty) independent sets. Then counts the number of colorings using exactly k colors (with distinguishable colors). For an integer x, all x-colorings of G can be uniquely obtained by choosing an integer k ≤ x, choosing k colors to be used out of x available, and a coloring using exactly those k (distinguishable) colors. Therefore:

where denotes the falling factorial. Thus the numbers are the coefficients of the polynomial in the basis of falling factorials.

Let be the k-th coefficient of in the standard basis , that is:

Stirling numbers give a change of basis between the standard basis and the basis of falling factorials. This implies:

- and

Categorification

[edit]The chromatic polynomial is categorified by a homology theory closely related to Khovanov homology.[10]

Algorithms

[edit]| Chromatic polynomial | |

|---|---|

| Input | Graph G with n vertices. |

| Output | Coefficients of |

| Running time | for some constant |

| Complexity | #P-hard |

| Reduction from | #3SAT |

| #k-colorings | |

|---|---|

| Input | Graph G with n vertices. |

| Output | |

| Running time | In P for . for . Otherwise for some constant |

| Complexity | #P-hard unless |

| Approximability | No FPRAS for |

Computational problems associated with the chromatic polynomial include

- finding the chromatic polynomial of a given graph G;

- evaluating at a fixed x for given G.

The first problem is more general because if we knew the coefficients of we could evaluate it at any point in polynomial time because the degree is n. The difficulty of the second type of problem depends strongly on the value of x and has been intensively studied in computational complexity. When x is a natural number, this problem is normally viewed as computing the number of x-colorings of a given graph. For example, this includes the problem #3-coloring of counting the number of 3-colorings, a canonical problem in the study of complexity of counting, complete for the counting class #P.

Efficient algorithms

[edit]For some basic graph classes, closed formulas for the chromatic polynomial are known. For instance this is true for trees and cliques, as listed in the table above.

Polynomial time algorithms are known for computing the chromatic polynomial for wider classes of graphs, including chordal graphs[11] and graphs of bounded clique-width.[12] The latter class includes cographs and graphs of bounded tree-width, such as outerplanar graphs.

Deletion–contraction

[edit]The deletion-contraction recurrence gives a way of computing the chromatic polynomial, called the deletion–contraction algorithm. In the first form (with a minus), the recurrence terminates in a collection of empty graphs. In the second form (with a plus), it terminates in a collection of complete graphs. This forms the basis of many algorithms for graph coloring. The ChromaticPolynomial function in the Combinatorica package of the computer algebra system Mathematica uses the second recurrence if the graph is dense, and the first recurrence if the graph is sparse.[13] The worst case running time of either formula satisfies the same recurrence relation as the Fibonacci numbers, so in the worst case, the algorithm runs in time within a polynomial factor of

on a graph with n vertices and m edges.[14] The analysis can be improved to within a polynomial factor of the number of spanning trees of the input graph.[15] In practice, branch and bound strategies and graph isomorphism rejection are employed to avoid some recursive calls, the running time depends on the heuristic used to pick the vertex pair.

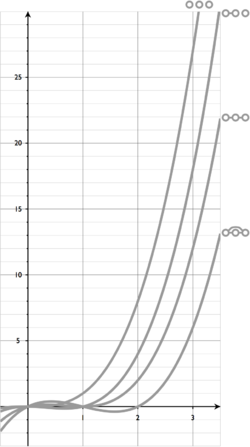

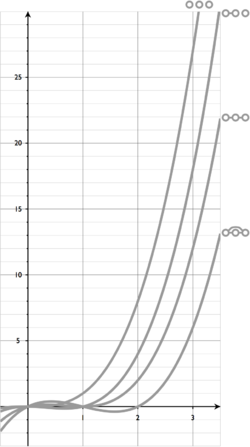

Cube method

[edit]There is a natural geometric perspective on graph colorings by observing that, as an assignment of natural numbers to each vertex, a graph coloring is a vector in the integer lattice. Since two vertices and being given the same color is equivalent to the ’th and ’th coordinate in the coloring vector being equal, each edge can be associated with a hyperplane of the form . The collection of such hyperplanes for a given graph is called its graphic arrangement. The proper colorings of a graph are those lattice points which avoid forbidden hyperplanes. Restricting to a set of colors, the lattice points are contained in the cube . In this context the chromatic polynomial counts the number of lattice points in the -cube that avoid the graphic arrangement.

Computational complexity

[edit]The problem of computing the number of 3-colorings of a given graph is a canonical example of a #P-complete problem, so the problem of computing the coefficients of the chromatic polynomial is #P-hard. Similarly, evaluating for given G is #P-complete. On the other hand, for it is easy to compute , so the corresponding problems are polynomial-time computable. For integers the problem is #P-hard, which is established similar to the case . In fact, it is known that is #P-hard for all x (including negative integers and even all complex numbers) except for the three “easy points”.[16] Thus, from the perspective of #P-hardness, the complexity of computing the chromatic polynomial is completely understood.

In the expansion

the coefficient is always equal to 1, and several other properties of the coefficients are known. This raises the question if some of the coefficients are easy to compute. However the computational problem of computing ar for a fixed r ≥ 1 and a given graph G is #P-hard, even for bipartite planar graphs.[17]

No approximation algorithms for computing are known for any x except for the three easy points. At the integer points , the corresponding decision problem of deciding if a given graph can be k-colored is NP-hard. Such problems cannot be approximated to any multiplicative factor by a bounded-error probabilistic algorithm unless NP = RP, because any multiplicative approximation would distinguish the values 0 and 1, effectively solving the decision version in bounded-error probabilistic polynomial time. In particular, under the same assumption, this rules out the possibility of a fully polynomial time randomised approximation scheme (FPRAS). There is no FPRAS for computing for any x > 2, unless NP = RP holds.[18]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Read (1968)

- ^ Several chapters Biggs (1993)

- ^ Dong, Koh & Teo (2005)

- ^ Stanley (1973)

- ^ Ellis-Monaghan & Merino (2011)

- ^ Huh (2012)

- ^ Chao & Whitehead (1978)

- ^ Jackson (1993)

- ^ Sokal (2004)

- ^ Helme-Guizon & Rong (2005)

- ^ Naor, Naor & Schaffer (1987).

- ^ Giménez, Hliněný & Noy (2005); Makowsky et al. (2006).

- ^ Pemmaraju & Skiena (2003)

- ^ Wilf (1986)

- ^ Sekine, Imai & Tani (1995)

- ^ Jaeger, Vertigan & Welsh (1990), based on a reduction in (Linial 1986).

- ^ Oxley & Welsh (2002)

- ^ Goldberg & Jerrum (2008)

References

[edit]- Biggs, N. (1993), Algebraic Graph Theory, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-45897-9

- Chao, C.-Y.; Whitehead, E. G. (1978), "On chromatic equivalence of graphs", Theory and Applications of Graphs, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 642, Springer, pp. 121–131, ISBN 978-3-540-08666-6

- Dong, F. M.; Koh, K. M.; Teo, K. L. (2005), Chromatic polynomials and chromaticity of graphs, World Scientific Publishing Company, ISBN 978-981-256-317-0

- Ellis-Monaghan, Joanna A.; Merino, Criel (2011), "Graph polynomials and their applications I: The Tutte polynomial", in Dehmer, Matthias (ed.), Structural Analysis of Complex Networks, arXiv:0803.3079, doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4789-6_9, ISBN 978-0-8176-4789-6, S2CID 585250

- Giménez, O.; Hliněný, P.; Noy, M. (2005), "Computing the Tutte polynomial on graphs of bounded clique-width", Proc. 31st Int. Worksh. Graph-Theoretic Concepts in Computer Science (WG 2005), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 3787, Springer-Verlag, pp. 59–68, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.353.6385, doi:10.1007/11604686_6, ISBN 978-3-540-31000-6

- Goldberg, L.A.; Jerrum, M. (2008), "Inapproximability of the Tutte polynomial", Information and Computation, 206 (7): 908, arXiv:cs/0605140, doi:10.1016/j.ic.2008.04.003, S2CID 53304001

- Helme-Guizon, Laure; Rong, Yongwu (2005), "A categorification of the chromatic polynomial", Algebraic & Geometric Topology, 5 (4): 1365–1388, arXiv:math/0412264, doi:10.2140/agt.2005.5.1365, S2CID 1339633

- Huh, June (2012), "Milnor numbers of projective hypersurfaces and the chromatic polynomial of graphs", Journal of the American Mathematical Society, 25 (3): 907–927, arXiv:1008.4749, doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-2012-00731-0, MR 2904577, S2CID 13523955

- Jackson, B. (1993), "A Zero-Free Interval for Chromatic Polynomials of Graphs", Combinatorics, Probability and Computing, 2 (3): 325–336, doi:10.1017/S0963548300000705, S2CID 39978844

- Jaeger, F.; Vertigan, D. L.; Welsh, D. J. A. (1990), "On the computational complexity of the Jones and Tutte polynomials", Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 108 (1): 35–53, Bibcode:1990MPCPS.108...35J, doi:10.1017/S0305004100068936, S2CID 121454726

- Linial, N. (1986), "Hard enumeration problems in geometry and combinatorics", SIAM J. Algebr. Discrete Methods, 7 (2): 331–335, doi:10.1137/0607036

- Makowsky, J. A.; Rotics, U.; Averbouch, I.; Godlin, B. (2006), "Computing graph polynomials on graphs of bounded clique-width", Proc. 32nd Int. Worksh. Graph-Theoretic Concepts in Computer Science (WG 2006), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 4271, Springer-Verlag, pp. 191–204, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.76.2320, doi:10.1007/11917496_18, ISBN 978-3-540-48381-6

- Naor, J.; Naor, M.; Schaffer, A. (1987), "Fast parallel algorithms for chordal graphs", Proc. 19th ACM Symp. Theory of Computing (STOC '87), pp. 355–364, doi:10.1145/28395.28433, ISBN 978-0897912211, S2CID 12132229.

- Oxley, J. G.; Welsh, D. J. A. (2002), "Chromatic, flow and reliability polynomials: The complexity of their coefficients.", Combinatorics, Probability and Computing, 11 (4): 403–426, doi:10.1017/S0963548302005175, S2CID 14918970

- Pemmaraju, S.; Skiena, S. (2003), Computational Discrete Mathematics: Combinatorics and Graph Theory with Mathematica, Cambridge University Press, section 7.4.2, ISBN 978-0-521-80686-2

- Read, R. C. (1968), "An introduction to chromatic polynomials" (PDF), Journal of Combinatorial Theory, 4: 52–71, doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(68)80087-0

- Sekine, Kyoko; Imai, Hiroshi; Tani, Seiichiro (1995), "Computing the Tutte polynomial of a graph of moderate size", in Staples, John; Eades, Peter; Katoh, Naoki; Moffat, Alistair (eds.), Algorithms and Computation, 6th International Symposium, ISAAC '95, Cairns, Australia, December 4–6, 1995, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 1004, Springer, pp. 224–233, doi:10.1007/BFb0015427, ISBN 978-3-540-60573-7

- Sokal, A. D. (2004), "Chromatic Roots are Dense in the Whole Complex Plane", Combinatorics, Probability and Computing, 13 (2): 221–261, arXiv:cond-mat/0012369, doi:10.1017/S0963548303006023, S2CID 5549332

- Stanley, R. P. (1973), "Acyclic orientations of graphs" (PDF), Discrete Math., 5 (2): 171–178, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(73)90108-8

- Voloshin, Vitaly I. (2002), Coloring Mixed Hypergraphs: Theory, Algorithms and Applications., American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-2812-0

- Wilf, H. S. (1986), Algorithms and Complexity, Prentice–Hall, ISBN 978-0-13-021973-2

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W., "Chromatic polynomial", MathWorld

- Chromatic polynomial at PlanetMath.

- Code for computing Tutte, Chromatic and Flow Polynomials by Gary Haggard, David J. Pearce and Gordon Royle: [1]

Chromatic polynomial

View on GrokipediaDefinition

Formal definition

The chromatic polynomial of a graph , denoted , counts the number of proper vertex colorings of using at most distinguishable colors, such that no two adjacent vertices receive the same color. The chromatic polynomial was introduced by George D. Birkhoff in 1912. Further developments, including the deletion-contraction recurrence, were made by Hassler Whitney in 1932.[6][7][4] A proper coloring assigns colors to the vertices of from a set of available colors in such a way that adjacent vertices must differ in color.[4] The function is a monic polynomial in the variable of degree , where is the number of vertices in , and it has integer coefficients that alternate in sign.[4][5] For any graph with at least one vertex, , which holds in particular for connected graphs containing edges; in general, the value of factors as the product over the chromatic polynomials of its connected components, thereby relating it to the number of such components.[4][6] For the introductory example of an edgeless graph on vertices, , since there are no adjacency constraints and each vertex may be colored freely.[4]Deletion-contraction recurrence

The deletion-contraction recurrence is a cornerstone for computing the chromatic polynomial of a graph , providing a recursive relation based on edge operations. For any non-loop edge in , the formula states: where denotes the deletion of (the graph with removed, preserving all other edges and vertices), and denotes the contraction of . This recurrence, introduced by Hassler Whitney, allows the polynomial to be expressed in terms of simpler subgraphs.[8] Contraction of an edge merges vertices and into a single new vertex , with all edges originally incident to or now incident to ; any self-loops formed in this process are removed, as loops prevent proper colorings. Deletion simply removes without altering vertices or other edges. These operations preserve the structure relevant to coloring counts while reducing the graph's complexity.[8] The proof relies on an inclusion-exclusion principle applied to proper -colorings. The quantity counts all proper colorings of , which include cases where the endpoints of receive the same color or different colors. Proper colorings of correspond precisely to those of where the endpoints have different colors, since forbids the same color. The colorings of where the endpoints share a color are in bijection with the proper colorings of , as contraction enforces the same color on the identified vertices. Subtracting thus isolates the valid colorings for .[8] Base cases anchor the recurrence. For a graph with a single vertex (edgeless with one vertex), , as there is one way to color it with each of colors. A graph containing a loop has for all , since no proper coloring exists. For the graph consisting of two vertices connected by a single edge, , accounting for choices of distinct colors for the endpoints. These cases handle terminal reductions in the recursion.[9] The recurrence defines a unique polynomial, as iterative application to any edge sequence reduces to disjoint unions of isolated vertices and possibly loops, yielding an expression that matches the number of proper colorings for all positive integers . The result is independent of the choice of edges or reduction order, confirming the well-definedness of as a polynomial of degree equal to the number of vertices in .[8]History

Origins in graph coloring

The study of graph coloring originated in the late 19th century as mathematicians sought to resolve the four-color theorem, which posits that any map can be colored with at most four colors such that no adjacent regions share the same color. In the 1880s, Peter Guthrie Tait advanced this area by examining edge colorings of cubic (3-regular) planar graphs, demonstrating that the four-color theorem is equivalent to the statement that every bridgeless cubic planar graph is 3-edge-colorable.[10] Tait's approach transformed the vertex-coloring problem of maps into an edge-coloring problem on their dual graphs, providing an early combinatorial framework for enumerating colorings without explicitly using polynomials.[10] Building on these foundations, George David Birkhoff introduced the concept of the chromatic polynomial in 1912 to quantify the number of proper vertex colorings of a graph as a function of the number of available colors, specifically targeting an algebraic proof of the four-color theorem for planar graphs. Birkhoff's formulation expressed the count of colorings via a determinant of a matrix derived from the graph's structure, offering a tool to bound the polynomial at four colors and thereby establish non-negativity for planar maps. This innovation shifted focus from qualitative colorability to quantitative enumeration, motivated primarily by the need to analyze map colorings systematically. In 1932, Hassler Whitney generalized and formalized Birkhoff's chromatic polynomial as an intrinsic invariant of arbitrary graphs, independent of planarity, and established key properties such as its monic nature and deletion-contraction recurrence. Whitney's work emphasized the polynomial's role in capturing the essence of proper colorings—assignments of colors to vertices such that no adjacent vertices share the same color—extending its utility beyond map problems to broader graph-theoretic inquiries. These early developments laid the groundwork for using chromatic enumeration to tackle scheduling and resource allocation modeled as graph colorings, though the primary impetus remained the four-color challenge.Key developments and contributors

In 1968, Ronald C. Read published a seminal expository paper that revitalized interest in chromatic polynomials by deriving their key properties, exploring computational methods for their evaluation, and providing explicit expressions for classes of graphs such as trees, where the polynomial simplifies to for a tree with vertices and colors.[11] During the 1960s and 1970s, Sami Beraha advanced the understanding of chromatic roots through his investigations into the four-color problem for planar graphs, introducing the Beraha numbers—such as , , and subsequent terms defined by —which identify potential accumulation points of non-integer real roots of chromatic polynomials for recursively constructible planar triangulations. In the mid-20th century, W. T. Tutte deepened connections between chromatic polynomials and broader algebraic structures by extending the dichromatic polynomial (now known as the Tutte polynomial) to matroids and exploring its universal properties, as detailed in his monograph on graph polynomials, which unified deletion-contraction recurrences across graphs and matroids while relating evaluations to chromatic counts. The 2000s saw the introduction of categorification techniques inspired by Khovanov's homology for links, with Laure Helme-Guizon and Yongwu Rong constructing graded cohomology groups for graphs whose Euler characteristic recovers the chromatic polynomial, thereby lifting the invariant to a richer homological structure.[12] Recent developments through 2025 include quantum algorithms leveraging string-net condensation and Fibonacci anyon braiding to approximate evaluations of chromatic polynomials for complex graphs, enabling scalable sampling that classical methods struggle with due to exponential growth.[13]Examples

Trees and paths

Trees provide simple yet illustrative examples for understanding the chromatic polynomial, as they are connected acyclic graphs. The path graph , which consists of vertices connected in a linear chain, has chromatic polynomial . This formula arises from direct enumeration of proper colorings: the endpoint vertex can be colored in ways, and each of the remaining vertices must differ in color from its unique neighbor, offering choices each.[1] More generally, every tree on vertices shares the identical chromatic polynomial , regardless of the specific tree structure. This uniformity can be established using the deletion-contraction recurrence: removing a leaf edge disconnects the graph into a smaller tree and an isolated vertex, whose chromatic polynomials multiply appropriately under the recurrence, leading by induction to the stated formula.[14] Alternatively, the result follows from counting rooted trees in colorings, where one vertex is chosen as root ( choices) and the remaining vertices are assigned colors differing from their parent ( choices each).[14] Trees are bipartite graphs, meaning their chromatic number is 2—they require at least two colors for a proper coloring but admit no odd cycles that would demand more. However, the chromatic polynomial enumerates all proper -colorings for any positive integer , yielding positive values for all while vanishing at and . This polynomial is monic of degree , with leading term , reflecting the total unrestricted colorings minus constraints from the edges. To illustrate, consider small paths (which are trees) and the number of proper colorings:- For (isolated vertex): , so 2 colors yield 2 colorings.

- For (single edge): , so 2 colors yield 2 colorings.

- For (path of three vertices): , so 2 colors yield 2 colorings.

- For (path of four vertices): , so 2 colors yield 2 colorings.

Cycles and complete graphs

The chromatic polynomial for the cycle graph with vertices is given bywhere is the number of available colors.[15] This formula arises from the deletion-contraction recurrence relation, which states that for any graph and edge , , where is with edge deleted and is with contracted.[16] Applying this recursively to reduces the problem to computing the polynomial for a path graph , which has the form .[15] The resulting expression exhibits an oscillatory behavior due to the alternating sign term, reflecting the cyclic structure: for even , the polynomial evaluates positively for , while for odd , it requires for positive values, aligning with the chromatic number of even and odd cycles, respectively.[15] A special case occurs when , where is isomorphic to the complete graph , the triangle. Substituting into the cycle formula yields , confirming the equivalence.[15] This derivation via deletion-contraction provides an inductive proof, starting from smaller cycles and building up, and can also be obtained through inclusion-exclusion principles counting colorings where adjacent vertices differ.[15] For the complete graph with vertices, where every pair of vertices is adjacent, the chromatic polynomial is the falling factorial

This follows directly from sequential vertex coloring: the first vertex has choices, the second has (to differ from the first), the third has (to differ from the first two), and so on, up to the -th vertex with choices.[16] The product form highlights the binomial nature, as it equals for integer , emphasizing the need for at least colors to properly color .[16] As an extension involving both cycles and complete subgraphs, the wheel graph (a cycle with an additional hub vertex connected to all rim vertices) has chromatic polynomial

This can be derived by first coloring the hub ( choices), then the rim as a cycle with restricted colors avoiding the hub's color ( effective colors), incorporating the cycle formula adjusted for the constraints.[17]

Properties

Fundamental theorems

The chromatic polynomial exhibits multiplicativity with respect to disjoint unions of graphs. Specifically, if and are two graphs with no vertices in common, then the chromatic polynomial of their disjoint union satisfies .[4] This property extends to disconnected graphs: if consists of connected components , then .[4] A proof sketch follows from the definition of proper colorings: since the components are independent, the total number of ways to color with colors is the product of the numbers for each component, as color assignments to vertices in different components impose no restrictions on each other.[4] The chromatic polynomial is always a monic polynomial of degree , where is the number of vertices in . Thus, it can be expressed as , with leading coefficient 1. To see this, note that the total number of vertex colorings without adjacency restrictions is , and the deletion-contraction recurrence subtracts terms that account for invalid colorings, preserving the degree and leading term by induction on the number of edges.[4] The coefficients of the chromatic polynomial alternate in sign. In the expansion , the are nonnegative integers, with and for . Stanley's theorem provides a combinatorial interpretation: the absolute values count the number of acyclic orientations of with exactly sinks (or equivalently, via duality, relate to broken cycle structures). A proof uses inclusion-exclusion on cycles in the graph, showing that the signed coefficients arise from overcounting colorings that violate independence along circuit edges, with induction on the number of vertices confirming the alternation.[18] Evaluating the chromatic polynomial at yields if has at least one edge, and if is edgeless.[4] This follows directly from the coloring interpretation: with one color, all vertices must receive the same color, which is proper only if no edges exist to connect same-colored adjacent vertices; in the edgeless case, there is exactly one such coloring. For disconnected graphs, the multiplicativity ensures the result holds as long as any component has an edge.[4]Chromatic equivalence and roots

Two graphs and are said to be chromatically equivalent if they have the same chromatic polynomial, denoted for all , even if and are not isomorphic.[19] This phenomenon highlights that the chromatic polynomial does not uniquely determine the isomorphism class of a graph.[20] A classic example occurs with trees: all trees on vertices are chromatically equivalent, sharing the polynomial , regardless of their specific structure.[21] For , the path graph and the star graph provide a pair of non-isomorphic chromatically equivalent graphs, both with .[22] The roots of the chromatic polynomial , known as chromatic roots, are the complex numbers satisfying .[23] These roots are algebraic integers, and their locations in the complex plane have been extensively studied, with known bounds excluding certain regions such as the disk except for specific cases.[24] For planar graphs, the four-color theorem implies that there are no chromatic roots at integers greater than or equal to 5, as for all integers .[25] More refined conjectures address real chromatic roots; for instance, it is conjectured that planar graphs have no real roots in the interval , building on the theorem's assurance that 4 is not a root.[26] In the context of planar triangulations, chromatic roots exhibit intriguing asymptotic behavior, often approaching the Beraha numbers, defined as for positive integers .[27] These numbers arise as potential accumulation points of roots for sequences of triangulations with increasing vertices, with early Beraha numbers including , , and .[28] The four-color theorem connects to this framework, as the absence of roots exceeding 4 aligns with roots clustering near 0, 1, 2, 3, or higher Beraha numbers rather than values greater than 4.[25] Numerical investigations into these root distributions for planar graphs have persisted into the 2020s, refining understandings of their density and limits, though comprehensive resolutions of related conjectures remain open.[29]Surjective colorings

The surjective chromatic polynomial of a graph , denoted , enumerates the proper vertex colorings of using exactly distinguishable colors, meaning every color is assigned to at least one vertex.[30] This variant emphasizes colorings where the color assignment is surjective onto the set of colors, distinguishing it from the standard chromatic polynomial , which permits unused colors.[31] The surjective chromatic polynomial relates to the standard one via inclusion-exclusion: This expression derives from subtracting overcounts of non-surjective colorings in the inclusion-exclusion framework applied to the image sizes of color maps.[31] Equivalently, , where denotes the graph Stirling number of the second kind, counting the partitions of into exactly nonempty independent sets.[31] The coefficients of the chromatic polynomial connect to acyclic orientations through Stanley's theorem, where and is the number of acyclic orientations of with components.[18] For the surjective variant, the transformation via Stirling numbers and inclusion-exclusion yields coefficients interpretable in terms of these orientations.[31] Such colorings correspond to surjective graph homomorphisms from to the complete graph . In the 2010s, results showed that mutual surjective homomorphisms between graphs imply identical chromatic polynomials, establishing a Cantor-Bernstein-like property for chromatic equivalence via these mappings.[32] Applications include fixed- enumerations in combinatorial partition functions and analyzing graph invariants under homomorphism counts.[33]Categorification

Categorification of the chromatic polynomial involves constructing higher categorical structures, such as chain complexes or homology theories, that lift the polynomial to graded invariants whose Euler characteristic recovers the original counting function. In particular, chromatic homology provides a graded vector space for a graph and integer , satisfying where the dimensions are taken over a suitable ground field and depend polynomially on .[34] This construction was introduced by Helme-Guizon and Rong in 2005, who defined graded cohomology groups for graphs via a chain complex based on cubical posets associated to the graph's edges, motivated by Khovanov's 2000 categorification of the Jones polynomial for links into Khovanov homology.[34] The resulting chromatic homology is analogous to Khovanov homology but adapted to graph structures, with chain groups generated by certain subgraphs or colorings that respect the deletion-contraction recurrence of the chromatic polynomial.[34] Key properties of chromatic homology include the recovery of the chromatic polynomial as its Euler characteristic and the provision of refined invariants through the ranks of the homology groups, which capture more detailed topological information than the polynomial alone.[34] For instance, the homology satisfies long exact sequences mirroring the deletion-contraction relation, ensuring compatibility with graph operations.[34] These ranks enable applications such as distinguishing pairs of chromatically equivalent graphs—those sharing the same chromatic polynomial but differing in structure—via non-isomorphic homology groups, as demonstrated for cochromatic polygon-trees and other examples over specific ground rings like . In the 2020s, extensions have addressed limitations in tying chromatic homology to broader algebraic topology, including developments in chromatic symmetric homology, which lifts Stanley's chromatic symmetric function and distinguishes graphs with identical symmetric functions while detecting planarity in certain cases.[29] Further advances include multipath cohomology for directed graphs, providing an oriented variant that builds on chromatic homology but accounts for arc directions, thus resolving its orientation-blindness.[35] Additionally, a 2025 spanning tree model reinterprets the chromatic complex using spanning trees, offering combinatorial generators that enhance computational and structural insights into the homology.[36]Computation

Recursive methods

The deletion-contraction recurrence provides the foundation for a recursive algorithm to compute the chromatic polynomial of a graph . For a non-empty edge set, select an edge ; the polynomial satisfies , where is the graph with deleted and is the graph with contracted by merging its endpoints into a single vertex (discarding any resulting loops). Base cases include the edgeless graph on vertices, where , and graphs containing loops, where . This recursive approach, based on the deletion-contraction recurrence, builds a recursion tree by repeatedly applying the relation until base cases are reached, with the final polynomial obtained by combining results via subtraction.[4][8][7] To mitigate redundant computations in the recursion tree—where isomorphic subgraphs may arise multiple times—implementations employ memoization, storing the chromatic polynomials of encountered subgraphs (often represented in canonical form) for reuse. This dynamic programming technique significantly reduces the effective number of unique subgraph evaluations, though the overall space required grows with the number of distinct subgraphs.[21] The time complexity of the basic recursive algorithm is exponential. In the worst case, such as for dense graphs, it requires operations, where is the th Bell number counting set partitions (growing asymptotically faster than for any constant but slower than ); this arises from the branching factor and the need to process up to partitions in the recursion. For sparse graphs with edges, the complexity improves to roughly , as the recursion depth and branching are bounded by the edge count.[37] Optimizations enhance efficiency for practical computations. Parallelization exploits the independent deletion and contraction branches, allowing simultaneous evaluation on multi-core systems to halve the effective time for balanced trees. Additionally, graph symmetries via automorphism groups reduce redundant branches by identifying equivalent edges or subgraphs for selective recursion, often using canonical labeling to prune isomorphic cases during memoization.[37] Software tools implement these recursive methods effectively. SageMath provides a built-inchromatic_polynomial function using a recursive deletion-contraction approach optimized with observations on edge ordering to minimize branching. The nauty package supports symmetry detection through graph canonization, which integrates with recursive implementations (e.g., in Maple or custom codes) to enable efficient memoization by avoiding duplicate computations on automorphic subgraphs.[38][39]

As an illustrative example, consider the 4-cycle graph with vertices and edges . Apply deletion-contraction to edge :

- Deletion: is a 4-path (---), an edgeless graph after known path reduction, yielding .

- Contraction: merges and into , forming a triangle --, with .

![{\displaystyle [0,k]^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8df6fe0f0693f5c9e7c12c2cb0e2631660d37344)

![{\displaystyle [0,k]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0dda1392a37e0feafb1454ceec449724ab056a3a)