Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Graph property

View on Wikipedia

In graph theory, a graph property or graph invariant is a property of graphs that depends only on the abstract structure, not on graph representations such as particular labellings or drawings of the graph.[1]

Definitions

[edit]While graph drawing and graph representation are valid topics in graph theory, in order to focus only on the abstract structure of graphs, a graph property is defined to be a property preserved under all possible isomorphisms of a graph. In other words, it is a property of the graph itself, not of a specific drawing or representation of the graph. Informally, the term "graph invariant" is used for properties expressed quantitatively, while "property" usually refers to descriptive characterizations of graphs. For example, the statement "graph does not have vertices of degree 1" is a "property" while "the number of vertices of degree 1 in a graph" is an "invariant".

More formally, a graph property is a class of graphs with the property that any two isomorphic graphs either both belong to the class, or both do not belong to it.[1] Equivalently, a graph property may be formalized using the indicator function of the class, a function from graphs to Boolean values that is true for graphs in the class and false otherwise; again, any two isomorphic graphs must have the same function value as each other. A graph invariant or graph parameter may similarly be formalized as a function from graphs to a broader class of values, such as integers, real numbers, sequences of numbers, or polynomials, that again has the same value for any two isomorphic graphs.[2]

Properties of properties

[edit]Many graph properties are well-behaved with respect to certain natural partial orders or preorders defined on graphs:

- A graph property P is hereditary if every induced subgraph of a graph with property P also has property P. For instance, being a perfect graph or being a chordal graph are hereditary properties.[1]

- A graph property is monotone if every subgraph of a graph with property P also has property P. For instance, being a bipartite graph or being a triangle-free graph is monotone. Every monotone property is hereditary, but not necessarily vice versa; for instance, subgraphs of chordal graphs are not necessarily chordal, so being a chordal graph is not monotone.[1]

- A graph property is minor-closed if every graph minor of a graph with property P also has property P. For instance, being a planar graph is minor-closed. Every minor-closed property is monotone, but not necessarily vice versa; for instance, minors of triangle-free graphs are not necessarily themselves triangle-free.[1]

These definitions may be extended from properties to numerical invariants of graphs: a graph invariant is hereditary, monotone, or minor-closed if the function formalizing the invariant forms a monotonic function from the corresponding partial order on graphs to the real numbers.

Additionally, graph invariants have been studied with respect to their behavior with regard to disjoint unions of graphs:

- A graph invariant is additive if, for all two graphs G and H, the value of the invariant on the disjoint union of G and H is the sum of the values on G and on H. For instance, the number of vertices is additive.[1]

- A graph invariant is multiplicative if, for all two graphs G and H, the value of the invariant on the disjoint union of G and H is the product of the values on G and on H. For instance, the Hosoya index (number of matchings) is multiplicative.[1]

- A graph invariant is maxing if, for all two graphs G and H, the value of the invariant on the disjoint union of G and H is the maximum of the values on G and on H. For instance, the chromatic number is maxing.[1]

In addition, graph properties can be classified according to the type of graph they describe: whether the graph is undirected or directed, whether the property applies to multigraphs, etc.[1]

Values of invariants

[edit]The target set of a function that defines a graph invariant may be one of:

- A truth-value, true or false, for the indicator function of a graph property.

- An integer, such as the number of vertices or chromatic number of a graph.

- A real number, such as the fractional chromatic number of a graph.

- A sequence of integers, such as the degree sequence of a graph.

- A polynomial, such as the Tutte polynomial of a graph.

Graph invariants and graph isomorphism

[edit]Easily computable graph invariants are instrumental for fast recognition of graph isomorphism, or rather non-isomorphism, since for any invariant at all, two graphs with different values cannot (by definition) be isomorphic. Two graphs with the same invariants may or may not be isomorphic, however.

A graph invariant I(G) is called complete if the identity of the invariants I(G) and I(H) implies the isomorphism of the graphs G and H. Finding an efficiently-computable such invariant (the problem of graph canonization) would imply an easy solution to the challenging graph isomorphism problem. However, even polynomial-valued invariants such as the chromatic polynomial are not usually complete. The claw graph and the path graph on 4 vertices both have the same chromatic polynomial, for example.

Examples

[edit]Properties

[edit]- Connected graphs

- Bipartite graphs

- Planar graphs

- Triangle-free graphs

- Perfect graphs

- Eulerian graphs

- Hamiltonian graphs

Integer invariants

[edit]- Order, the number of vertices

- Size, the number of edges

- Number of connected components

- Circuit rank, a linear combination of the numbers of edges, vertices, and components

- diameter, the longest of the shortest path lengths between pairs of vertices

- girth, the length of the shortest cycle

- Vertex connectivity, the smallest number of vertices whose removal disconnects the graph

- Edge connectivity, the smallest number of edges whose removal disconnects the graph

- Chromatic number, the smallest number of colors for the vertices in a proper coloring

- Chromatic index, the smallest number of colors for the edges in a proper edge coloring

- Choosability (or list chromatic number), the least number k such that G is k-choosable

- Independence number, the largest size of an independent set of vertices

- Clique number, the largest order of a complete subgraph

- Arboricity

- Graph genus

- Pagenumber

- Hosoya index

- Wiener index

- Colin de Verdière graph invariant

- Boxicity

Real number invariants

[edit]- Clustering coefficient

- Betweenness centrality

- Fractional chromatic number

- Algebraic connectivity

- Isoperimetric number

- Estrada index

- Strength

Sequences and polynomials

[edit]- Degree sequence

- Graph spectrum

- Characteristic polynomial of the adjacency matrix

- Chromatic polynomial, the number of -colorings viewed as a function of

- Tutte polynomial, a bivariate function that encodes much of the graph's connectivity

Edge partition

[edit]- (a, b)-decomposition for any natural a,b

See also

[edit]- Hereditary property

- Logic of graphs, one of several formal languages used to specify graph properties

- Topological index, a closely related concept in chemical graph theory

External links

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lovász, László (2012), "4.1 Graph parameters and graph properties", Large Networks and Graph Limits, Colloquium Publications, vol. 60, American Mathematical Society, pp. 41–42, ISBN 978-1-4704-1583-9.

- ^ Nešetřil, Jaroslav; Ossona de Mendez, Patrice (2012), "3.10 Graph Parameters", Sparsity: Graphs, Structures, and Algorithms, Algorithms and Combinatorics, vol. 28, Springer, pp. 54–56, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-27875-4, ISBN 978-3-642-27874-7, MR 2920058.

Graph property

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Definition

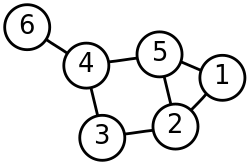

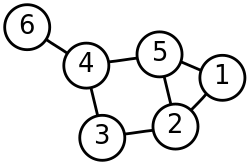

In graph theory, a graph is formally defined as an ordered pair , where is a finite set of vertices (also called nodes) and is a set of unordered pairs of distinct vertices from , representing edges that connect them.[5] This structure captures pairwise relationships between elements, such as connections in networks or dependencies in systems. A graph isomorphism is a bijective mapping between the vertex sets of two graphs and such that two vertices in are adjacent if and only if their images under are adjacent in .[6] Isomorphic graphs are considered structurally identical, differing only in the labeling or naming of their vertices and edges. A graph property is a family of graphs that is closed under isomorphism; that is, for a subset of all possible graphs, if and is isomorphic to , then .[3] Equivalently, it is any characteristic of graphs that depends solely on their abstract structure, independent of specific vertex or edge labels. Graph properties are typically defined on unlabeled graphs, which are equivalence classes of labeled graphs under isomorphism, ensuring that relabeling does not alter membership in .[7] In contrast, labeled graphs assign distinct identifiers to vertices, but properties ignore such labels to focus on relational structure. Basic examples include being a simple graph (no loops or multiple edges between the same pair of vertices), which is essential in modeling real-world networks without self-references or duplicate connections; being undirected (edges have no direction), common in symmetric relations like social ties; and being finite, which aligns with computational tractability in algorithm design and analysis.[5] These properties provide foundational building blocks for more complex analyses in areas such as optimization and data representation. Graph invariants, such as the number of vertices, represent a subclass where the property assigns a specific value preserved under isomorphism rather than a binary yes/no classification.Invariance under Graph Isomorphism

Graph isomorphism is defined as a bijective mapping between the vertex sets of two graphs that preserves the adjacency relation, meaning two vertices are adjacent in one graph if and only if their images under the mapping are adjacent in the other.[8] This structure-preserving bijection ensures that isomorphic graphs have identical connectivity patterns, disregarding any arbitrary labeling of vertices.[9] Graph properties are required to be invariant under isomorphism to capture the intrinsic structural features of a graph, independent of vertex labels or representations, thereby avoiding inconsistencies arising from superficial labeling differences.[10] To see this formally, suppose and are isomorphic via a bijection that preserves edges, and let be a property defined solely in terms of adjacency relations. If holds, then for any edge or non-edge in , the corresponding structure in under satisfies the same relational conditions, implying also holds; otherwise, would depend on labeling artifacts rather than the underlying structure, leading to contradictory classifications of equivalent graphs.[11] This invariance principle ensures that properties reliably distinguish graphs based on their combinatorial essence.[12] The foundational role of isomorphism invariance was recognized early in graph theory's development, notably in Hassler Whitney's 1932 work on congruent graphs, which explored mappings preserving graph connectivity,[13] and in Dénes Kőnig's 1936 monograph Theory of Finite and Infinite Graphs, which systematized graph structures with explicit consideration of isomorphisms in classification.[14] These contributions underscored invariance as essential to the field's theoretical framework. Such invariance has profound implications for graph recognition, as it permits the categorization of graphs up to isomorphism, treating all relabelings of the same structure as equivalent and facilitating the study of graph classes without regard to representational details.[9] This approach underpins algorithms and theorems that classify graphs by shared properties, enabling efficient identification of structural similarities across diverse applications.[15]Classification of Properties

Hereditary Properties

A hereditary graph property is a class of graphs that is closed under the operation of taking induced subgraphs. Formally, if a graph belongs to the property and is an induced subgraph of , then also belongs to . This closure ensures that the property is preserved when vertices and the edges between them are removed, making it "inherited" by substructures. Such properties are fundamental in graph theory because they capture structural constraints that remain invariant under vertex deletion.[4] Hereditary properties are precisely those that can be characterized by a family of forbidden induced subgraphs, possibly infinite. That is, a graph belongs to if and only if it contains none of the graphs in the forbidden family as an induced subgraph. The minimal elements of fully define the property, as any graph inducing a forbidden subgraph must contain a minimal one. This characterization distinguishes hereditary properties from minor-closed ones, which are closed under both vertex/edge deletions and contractions but form a stricter class—all minor-closed properties are hereditary, but the converse does not hold, as contractions can introduce structures absent in induced subgraphs alone. For instance, the property of being claw-free (no induced ) is hereditary but not minor-closed, since edge contractions may create claws.[16][17] Examples of hereditary properties abound in structural graph theory. The class of edgeless graphs is hereditary, forbidden by the induced (a single edge). Bipartite graphs form a hereditary class, as they forbid all induced odd cycles of length at least 3. Chordal graphs, which admit perfect elimination orderings, are hereditary and characterized by the absence of induced cycles of length 4 or more. These examples illustrate how forbidden induced subgraphs provide a clean structural description, often leading to algorithmic or extremal insights.[4] In applications, hereditary properties play a central role in structural graph theory, particularly in the study of perfect graphs. The Strong Perfect Graph Theorem establishes that a graph is perfect—meaning its chromatic number equals its clique number for every induced subgraph—if and only if it contains no induced odd hole (cycle of length at least 5) or odd antihole. This characterization underscores the significance of hereditary closure in resolving long-standing conjectures and enabling polynomial-time recognition algorithms for such classes.[18]Monotone Properties

In graph theory, a property of graphs is monotone increasing with respect to edges if, whenever a graph satisfies , then any supergraph of obtained by adding edges also satisfies ; similarly, is monotone decreasing with respect to edges if any subgraph obtained by deleting edges from also satisfies .[19] These properties can also be defined with respect to vertices, where adding or removing vertices (along with their incident edges) preserves the property, though edge-monotone variants are more commonly studied, particularly for properties like connectivity that depend primarily on edge structure.[19] Many decision problems in graph theory that are NP-complete correspond to monotone properties; for instance, Hamiltonicity—the property of containing a Hamiltonian cycle—is monotone increasing, as adding edges to a Hamiltonian graph yields another Hamiltonian graph.[20] [19] Representative examples include connectivity, which is monotone increasing under edge addition (since adding edges cannot disconnect a connected graph), and acyclicity (being forest-like), which is monotone decreasing under edge addition (or equivalently, increasing under edge deletion, as adding edges can create cycles).[19] Monotone properties play a central role in extremal graph theory, where the goal is often to determine the maximum number of edges in a graph satisfying a monotone decreasing property, such as avoiding a forbidden subgraph . Turán's theorem provides the foundational result in this area, stating that the maximum number of edges in an -vertex graph without a complete subgraph is achieved by the balanced complete -partite graph , with .[19] This theorem, originally proved in 1941, exemplifies how monotone decreasing properties like -freeness lead to precise extremal bounds and constructions.[19] Hereditary properties, which are closed under induced subgraph deletion, form a subclass of edge- and vertex-monotone decreasing properties.[21]Graph Invariants

Definition and Role

In graph theory, a graph invariant is a function that assigns to each graph a value from a specified codomain—such as the integers, real numbers, or other mathematical structures—such that isomorphic graphs receive identical values. This ensures the invariant depends solely on the abstract structure of the graph, remaining unchanged under relabeling of vertices or other isomorphisms.[22] Unlike general graph properties, which are typically binary and indicate whether a graph satisfies a yes/no condition (such as planarity or connectivity), graph invariants yield quantitative outputs that capture measurable aspects of the graph's structure.[11] This quantitative nature allows invariants to provide finer-grained distinctions between non-isomorphic graphs, serving as tools for partial isomorphism testing where equal invariant values suggest possible similarity but do not guarantee isomorphism.[23] A complete invariant, by contrast, fully resolves the isomorphism problem: two graphs are isomorphic if and only if their invariant values match.[24] Graph invariants play a central role in graph theory by enabling the classification and comparison of graphs without explicit isomorphism checks, which is computationally challenging.[22] Basic examples include the order of a graph , defined as , the number of vertices, and the size, defined as , the number of edges; both are preserved under isomorphism and provide initial filters for distinguishing graphs.[25] The development of graph invariants has paralleled efforts to address the graph isomorphism problem since the early 20th century, with significant contributions from George Pólya in his 1937 work on combinatorial enumeration, where invariants facilitated counting distinct graphs up to isomorphism via group actions.[26]Computational Aspects

The computational complexity of determining graph invariants varies widely, with some admitting efficient polynomial-time algorithms while others are NP-hard or worse. Efficient algorithms exist for several fundamental invariants. Connectivity, which measures whether a graph is connected or the number of its connected components, can be computed using breadth-first search (BFS) or depth-first search (DFS), both running in O(|V| + |E|) time by traversing the graph from an arbitrary starting vertex and identifying reachable components. The diameter, the longest shortest path between any pair of vertices, is also in P and can be found by running BFS from each vertex, yielding an O(|V|(|V| + |E|)) algorithm, though approximations or heuristics improve practicality for large graphs. For the chromatic number, which gives the minimum colors needed to color vertices without adjacent same-color pairs, exact computation is NP-hard, but the greedy coloring algorithm provides an approximation using at most Δ + 1 colors, where Δ is the maximum degree, by sequentially assigning the smallest available color to each vertex in a fixed order.[27] Graph invariants play a key role in isomorphism testing, where the goal is to determine if two graphs are structurally identical up to relabeling. Many invariants, such as the degree sequence or spectrum, serve as quick heuristics: if they differ, the graphs are non-isomorphic, but equality does not confirm isomorphism. The full graph isomorphism (GI) problem was long open regarding its placement in P, but in 2015, László Babai announced a quasi-polynomial time algorithm running in exp(O((log n)^c)) time for some constant c, an improvement over subexponential bounds; subsequent refinements in 2017 and 2018 maintained this quasi-polynomial complexity without resolving it to strict polynomial time as of 2025.[28][29] Recent advances leverage machine learning for approximating hard-to-compute invariants on large graphs. Graph neural networks (GNNs), which propagate node features through message-passing layers to produce permutation-invariant embeddings, have shown promise in estimating invariants like the clique number or clustering coefficient by training on graph datasets, often achieving sublinear-time approximations that outperform traditional heuristics in scalability.[30][31]| Invariant | Complexity Class |

|---|---|

| Connectivity | P (O( |

| Diameter | P (O( |

| Chromatic number | NP-hard |