Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Graph automorphism

View on WikipediaIn the mathematical field of graph theory, an automorphism of a graph is a form of symmetry in which the graph is mapped onto itself while preserving the edge–vertex connectivity.

Formally, an automorphism of a graph G = (V, E) is a permutation σ of the vertex set V, such that the pair of vertices (u, v) form an edge if and only if the pair (σ(u), σ(v)) also form an edge. That is, it is a graph isomorphism from G to itself. Automorphisms may be defined in this way both for directed graphs and for undirected graphs. The composition of two automorphisms is another automorphism, and the set of automorphisms of a given graph, under the composition operation, forms a group, the automorphism group of the graph. In the opposite direction, by Frucht's theorem, all groups can be represented as the automorphism group of a connected graph – indeed, of a cubic graph.[1][2]

Computational complexity

[edit]Constructing the automorphism group of a graph, in the form of a list of generators, is polynomial-time equivalent to the graph isomorphism problem, and therefore solvable in quasi-polynomial time, that is with running time for some fixed .[3][4] Consequently, like the graph isomorphism problem, the problem of finding a graph's automorphism group is known to belong to the complexity class NP, but not known to be in P nor to be NP-complete, and therefore may be NP-intermediate.

The easier problem of testing whether a graph has any symmetries (nontrivial automorphisms), known as the graph automorphism problem, also has no known polynomial time solution.[5] There is a polynomial time algorithm for solving the graph automorphism problem for graphs where vertex degrees are bounded by a constant.[6] The graph automorphism problem is polynomial-time many-one reducible to the graph isomorphism problem, but the converse reduction is unknown.[3][7][8] By contrast, hardness is known when the automorphisms are constrained in a certain fashion; for instance, determining the existence of a fixed-point-free automorphism (an automorphism that fixes no vertex) is NP-complete, and the problem of counting such automorphisms is ♯P-complete.[5][8]

Algorithms, software and applications

[edit]While no worst-case polynomial-time algorithms are known for the general Graph Automorphism problem, finding the automorphism group (and printing out an irredundant set of generators) for many large graphs arising in applications is rather easy. Several open-source software tools are available for this task, including NAUTY,[9] BLISS[10] and SAUCY.[11][12] SAUCY and BLISS are particularly efficient for sparse graphs, e.g., SAUCY processes some graphs with millions of vertices in mere seconds. However, BLISS and NAUTY can also produce Canonical Labeling, whereas SAUCY is currently optimized for solving Graph Automorphism. An important observation is that for a graph on n vertices, the automorphism group can be specified by no more than generators, and the above software packages are guaranteed to satisfy this bound as a side-effect of their algorithms (minimal sets of generators are harder to find and are not particularly useful in practice). It also appears that the total support (i.e., the number of vertices moved) of all generators is limited by a linear function of n, which is important in runtime analysis of these algorithms. However, this has not been established for a fact, as of March 2012.

Practical applications of Graph Automorphism include graph drawing and other visualization tasks, solving structured instances of Boolean Satisfiability arising in the context of Formal verification and Logistics. Molecular symmetry can predict or explain chemical properties.

Symmetry display

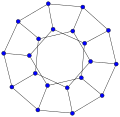

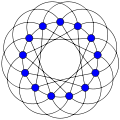

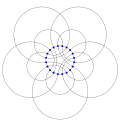

[edit]Several graph drawing researchers have investigated algorithms for drawing graphs in such a way that the automorphisms of the graph become visible as symmetries of the drawing. This may be done either by using a method that is not designed around symmetries, but that automatically generates symmetric drawings when possible,[13] or by explicitly identifying symmetries and using them to guide vertex placement in the drawing.[14] It is not always possible to display all symmetries of the graph simultaneously, so it may be necessary to choose which symmetries to display and which to leave unvisualized.

Graph families defined by their automorphisms

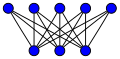

[edit]Several families of graphs are defined by having certain types of automorphisms:

- An asymmetric graph is an undirected graph with only the trivial automorphism.

- A vertex-transitive graph is an undirected graph in which every vertex may be mapped by an automorphism into any other vertex.

- An edge-transitive graph is an undirected graph in which every edge may be mapped by an automorphism into any other edge.

- A symmetric graph is a graph such that every pair of adjacent vertices may be mapped by an automorphism into any other pair of adjacent vertices.

- A distance-transitive graph is a graph such that every pair of vertices may be mapped by an automorphism into any other pair of vertices that are the same distance apart.

- A semi-symmetric graph is a graph that is edge-transitive but not vertex-transitive.

- A half-transitive graph is a graph that is vertex-transitive and edge-transitive but not symmetric.

- A skew-symmetric graph is a directed graph together with a permutation σ on the vertices that maps edges to edges but reverses the direction of each edge. Additionally, σ is required to be an involution.

Inclusion relationships between these families are indicated by the following table:

|

|

| ||

| distance-transitive | distance-regular | strongly regular | ||

|

|

|||

| symmetric (arc-transitive) | t-transitive, t ≥ 2 | |||

|

|

| ||

| vertex- and edge-transitive | edge-transitive and regular | edge-transitive | ||

|

|

|||

| vertex-transitive | regular | |||

|

||||

| Cayley graph |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Frucht, R. (1938), "Herstellung von Graphen mit vorgegebener abstrakter Gruppe", Compositio Mathematica (in German), 6: 239–250, ISSN 0010-437X, Zbl 0020.07804.

- ^ Frucht, R. (1949), "Graphs of degree three with a given abstract group", Canadian Journal of Mathematics, 1 (4): 365–378, doi:10.4153/CJM-1949-033-6, ISSN 0008-414X, MR 0032987, S2CID 124723321.

- ^ a b Mathon, R. (1979). "A note on the graph isomorphism counting problem". Information Processing Letters. 8 (3): 131–132. doi:10.1016/0020-0190(79)90004-8.

- ^ Dona, Daniele; Bajpai, Jitendra; Helfgott, Harald Andrés (October 12, 2017). "Graph isomorphisms in quasi-polynomial time". arXiv:1710.04574 [math.GR].

- ^ a b Lubiw, Anna (1981), "Some NP-complete problems similar to graph isomorphism", SIAM Journal on Computing, 10 (1): 11–21, doi:10.1137/0210002, MR 0605600.

- ^ Luks, Eugene M. (1982), "Isomorphism of graphs of bounded valence can be tested in polynomial time", Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 25 (1): 42–65, doi:10.1016/0022-0000(82)90009-5.

- ^ Köbler, Johannes; Schöning, Uwe; Torán, Jacobo (1993), Graph Isomorphism Problem: The Structural Complexity, Birkhäuser Verlag, ISBN 0-8176-3680-3, OCLC 246882287

- ^ a b Torán, Jacobo (2004). "On the hardness of graph isomorphism" (PDF). SIAM Journal on Computing. 33 (5): 1093–1108. doi:10.1137/S009753970241096X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ^ McKay, Brendan (1981), "Practical Graph Isomorphism" (PDF), Congressus Numerantium, 30: 45–87, retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ^ Junttila, Tommi; Kaski, Petteri (2007), "Engineering an efficient canonical labeling tool for large and sparse graphs" (PDF), Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop on Algorithm Engineering and Experiments (ALENEX07).

- ^ Darga, Paul; Sakallah, Karem; Markov, Igor L. (June 2008), "Faster symmetry discovery using sparsity of symmetries", Proceedings of the 45th annual Design Automation Conference (PDF), pp. 149–154, doi:10.1145/1391469.1391509, ISBN 978-1-60558-115-6, S2CID 15629172, archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-01-26, retrieved 2011-04-14.

- ^ Katebi, Hadi; Sakallah, Karem; Markov, Igor L. (July 2010), "Symmetry and Satisfiability: An Update" (PDF), Proc. Satisfiability Symposium (SAT).

- ^ Di Battista, Giuseppe; Tamassia, Roberto; Tollis, Ioannis G. (1992), "Area requirement and symmetry display of planar upward drawings", Discrete and Computational Geometry, 7 (1): 381–401, doi:10.1007/BF02187850; Eades, Peter; Lin, Xuemin (2000), "Spring algorithms and symmetry", Theoretical Computer Science, 240 (2): 379–405, doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(99)00239-X.

- ^ Hong, Seok-Hee (2002), "Drawing graphs symmetrically in three dimensions", Proc. 9th Int. Symp. Graph Drawing (GD 2001), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 2265, Springer-Verlag, pp. 106–108, doi:10.1007/3-540-45848-4_16, ISBN 978-3-540-43309-5.

External links

[edit]Graph automorphism

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In graph theory, a graph is typically denoted as , where is the set of vertices and is the set of edges representing unordered pairs of distinct vertices.[6] An automorphism of an undirected graph is a bijective mapping such that for all distinct vertices , the pair belongs to if and only if belongs to .[1] This permutation of the vertices preserves the adjacency relation, meaning it maps the graph onto itself while maintaining its structural properties.[2] A graph automorphism is a special case of a graph isomorphism, where the mapping is from the graph to itself rather than between two potentially distinct graphs.[2] Specifically, while a graph isomorphism requires that if and only if for graphs and , an automorphism restricts this to .[7] The concept extends naturally to directed graphs, denoted where consists of ordered pairs (arcs). An automorphism here is a bijection such that if and only if , preserving the direction of edges.[8] For weighted graphs, where each edge or is assigned a weight , an automorphism must additionally satisfy for all such pairs, ensuring weights are preserved under the mapping.[9] The set of all automorphisms of a graph , denoted , forms a group under the operation of function composition, with the identity mapping as the neutral element and inverses given by the inverse permutations.[1] This automorphism group captures the symmetries of and is a subgroup of the symmetric group on .[10]Basic Properties

Graph automorphisms preserve fundamental structural invariants of the graph, including the degree sequence, the number of edges, and connectivity properties, as they maintain adjacency relations between vertices.[1] Specifically, since an automorphism maps adjacent vertices to adjacent vertices and non-adjacent to non-adjacent, the degrees of vertices remain unchanged, ensuring the sorted list of degrees is invariant.[1] The total number of edges is preserved because the mapping is a bijection on the edge set, and connectivity—such as the graph being connected or the number of connected components—is unaltered under this symmetry.[1] In matrix terms, an automorphism corresponds to a permutation matrix such that if is the adjacency matrix of the graph, then .[11] This equation reflects the preservation of adjacency: the -entry of equals 1 if and only if the permuted entries match, confirming the structure is unchanged.[11] Automorphisms act as permutations on the vertex set, partitioning vertices into orbits under the group action, where an orbit consists of all vertices reachable from a given vertex via repeated applications of automorphisms.[1] Fixed points are vertices in singleton orbits, remaining unchanged by every automorphism in the group.[1] In the cycle decomposition of the permutation representation, cycles correspond to the symmetric mappings within orbits, illustrating how the automorphism rearranges vertices while preserving the graph's edges.[1] Since automorphisms preserve adjacency, they also preserve graph distances, defined as the length of shortest paths between vertices; this holds generally but is particularly structured in distance-regular graphs, where the number of vertices at a fixed distance from any vertex is constant.[12]Examples

A simple example of a graph automorphism is provided by the complete graph , also known as the triangle, which consists of three vertices all connected to each other. The automorphisms of include permutations of the vertices that preserve adjacency, such as cyclic rotations (mapping vertices 1 to 2, 2 to 3, and 3 to 1) and reflections (such as swapping vertices 2 and 3 while fixing 1). The full automorphism group is isomorphic to the symmetric group of order 6.[13] Cycle graphs for exhibit rotational and reflectional symmetry. An automorphism here corresponds to rotating the cycle or reflecting it over an axis through a vertex and the midpoint of the opposite edge. The automorphism group is isomorphic to the dihedral group of order , consisting of rotations and reflections.[14] Complete graphs on vertices, where every pair of distinct vertices is adjacent, have the maximum possible symmetry among graphs with vertices. Any permutation of the vertices preserves the complete set of edges, so is isomorphic to the symmetric group of order .[15] Path graphs on vertices, formed by connecting vertices in a linear sequence (e.g., vertices 1-2-...-n), have limited symmetry. For , the only non-trivial automorphism is the reflection that reverses the path, mapping vertex to . Thus, , the cyclic group of order 2.[13] The Petersen graph, a 3-regular graph on 10 vertices often drawn as an outer pentagon, an inner star, and connections between them, is a more complex example with high symmetry despite its non-planar structure. Its automorphism group has order 120 and is isomorphic to the symmetric group .[16]Automorphism Groups

Group Structure

The automorphism group of a graph consists of all bijections that preserve adjacency and non-adjacency, forming a group under composition.[17] This group embeds naturally as a subgroup of the symmetric group , where each automorphism corresponds to a permutation of the vertex set that maintains the graph's structure.[1] The action of on the vertex set is faithful, meaning the kernel of the action is trivial: no non-identity automorphism fixes every vertex, ensuring that is isomorphic to its image in .[17] This faithful permutation representation highlights how symmetries of the graph translate directly into permutations without redundancy. is generated by a set of permutations that reflect the graph's symmetries, often expressible in terms of cycles or transpositions corresponding to basic transformations like rotations or reflections in highly symmetric graphs.[1] For instance, in vertex-transitive graphs, generators can be chosen to include elements that cycle vertices within orbits, with the minimal number of such generators bounded by in many cases.[17] Key subgroups of include the stabilizers of individual vertices or edges; the vertex stabilizer consists of automorphisms fixing a particular vertex , and similarly for edges, these stabilizers capture local symmetries.[1] Normal subgroups arise in the structure of when considering quotients that preserve the permutation action, such as minimal normal subgroups in primitive actions, which often take abelian forms like elementary abelian -groups.[17] Early foundational work linking group actions to graphical enumerations dates to Arthur Cayley in 1878, who introduced representations of abstract groups via labeled digraphs, paving the way for modern understandings of automorphism groups as permutation groups acting on graphs.[18]Order and Orbit-Stabilizer Theorem

The order of the automorphism group of a graph with vertex set of size can be determined using tools from group theory, particularly the orbit-stabilizer theorem, which relates the size of the group to the sizes of orbits and stabilizers under its natural action on the vertices. The orbit-stabilizer theorem states that for any vertex , , where is the orbit of and is the stabilizer subgroup fixing . This relation holds because acts as a permutation group on , and the theorem applies to any group action.[17] If is vertex-transitive (i.e., acts transitively on , so for all ), then . The size of the stabilizer can often be computed by examining the action on the neighbors of or other structural features.[1] For non-transitive graphs, the order is the product of the sizes of the orbits times the orders of their corresponding stabilizers, obtained recursively by applying the theorem to the orbits and their point stabilizers.[17] This recursive application leverages the structure of the permutation representation of to build up the full order without enumerating all elements. Burnside's lemma provides a complementary tool for analyzing the action of by counting the number of orbits in related sets, such as proper vertex colorings or subgraphs, via the average number of fixed points: the number of orbits is , where is the number of elements fixed by . Although this formula requires knowledge of to apply directly, it can verify computed orders by checking consistency with known orbit counts in symmetric structures.[1] For example, consider the cycle graph on 4 vertices, which is vertex-transitive. The stabilizer of any vertex consists of the identity and the reflection through that vertex and its opposite, so . Thus, , corresponding to the dihedral group of order 8. Similarly, for the complete graph , (permutations of the remaining vertices), yielding .Computational Aspects

Complexity of Recognition

The decision problem of determining whether a given graph has a non-identity automorphism, often denoted as the GRAPH AUTOMORPHISM problem, lies in the complexity class NP. A nondeterministic Turing machine can solve it by guessing a permutation of the vertices and verifying in polynomial time whether it preserves the edge set, thereby confirming a nontrivial automorphism if one exists.[19] However, the problem is not known to be NP-complete; while restricted variants, such as deciding the existence of a fixed-point-free automorphism, are NP-complete, the general case is widely believed to be NP-intermediate.[20] The GRAPH AUTOMORPHISM problem is intimately related to the GRAPH ISOMORPHISM problem, with both residing in NP and sharing equivalent reductions in many settings. In 2015, László Babai announced a quasi-polynomial-time algorithm for GRAPH ISOMORPHISM, running in time for some constant , which implies the same complexity for recognizing nontrivial automorphisms since the automorphism group can be computed using a polynomial number of isomorphism tests.[21] This breakthrough was confirmed through subsequent refinements and verifications in the 2020s, establishing quasi-polynomial solvability for both problems without resolving whether they are in P.[22] In the worst case, naive algorithms for GRAPH AUTOMORPHISM require exponential time, such as for exhaustive search over all permutations of vertices, reflecting the inherent difficulty for dense or highly symmetric graphs. However, for graphs of bounded maximum degree , Luks developed a polynomial-time algorithm in 1982, leveraging group-theoretic techniques to reduce the search space effectively. As of 2025, no polynomial-time algorithm exists for the general GRAPH AUTOMORPHISM problem, maintaining its status as a cornerstone of complexity theory. Recent developments have focused on algebraic approaches, including linear algebra methods over finite fields, which enhance decomposition techniques in Babai's framework and yield improved bounds for structured graph classes, though the general case remains quasi-polynomial.[23]Connection to Graph Isomorphism

Graph automorphisms play a central role in addressing the graph isomorphism problem, which asks whether two graphs are structurally identical up to relabeling of vertices. The automorphism group Aut(G) of a graph G encodes the symmetries of G, and these symmetries can be leveraged to reduce isomorphism testing to more tractable computations. Specifically, by identifying invariants under Aut(G), one can map non-isomorphic labelings to a common representative form, allowing direct comparison of graphs for isomorphism.[24] A key technique linking automorphisms to isomorphism is canonical labeling, which assigns to each graph a unique labeling invariant under its automorphism group. This process reduces the isomorphism problem to equality checking: two graphs are isomorphic if and only if their canonical labelings are identical. Computing a canonical form involves exploring the orbits of Aut(G) to select a "minimal" labeling among all possible automorphic equivalents, often using backtrack search refined by symmetry detection. For instance, Brendan McKay's algorithm in the nauty software package computes such labelings by generating automorphisms to prune redundant branches, achieving practical efficiency for graphs up to thousands of vertices. This approach exploits the structure of Aut(G) to avoid enumerating all n! labelings, particularly when |Aut(G)| is large, as symmetries collapse many equivalents into fewer orbits.[25][26] The Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) method provides another bridge between automorphisms and isomorphism through color refinement, which iteratively partitions vertices into color classes based on neighborhood structures. Stabilizers in this refinement process correspond to orbits under Aut(G), as equivalent vertices under automorphism receive the same color. The k-dimensional WL algorithm stabilizes to reveal these orbits, enabling isomorphism testing by comparing refined color partitions; if the partitions differ, the graphs are non-isomorphic. This connection highlights how Aut(G) influences the method's power: full orbit detection via WL often suffices for practical isomorphism, though higher dimensions may be needed for graphs with rich symmetries. The original formulation by Weisfeiler and Lehman in 1968, extended in Weisfeiler's 1976 work, ties the method to cellular algebras where automorphism groups act as centralizers preserving orbit structures.[27] The size and structure of Aut(G) further modulate the difficulty of isomorphism testing. If Aut(G) is trivial (i.e., |Aut(G)| = 1, containing only the identity), isomorphism becomes relatively easier, as there are no non-trivial symmetries to account for in matching vertices, allowing straightforward refinement without orbit collapsing. Conversely, a large Aut(G) can aid efficiency by reducing the search space through symmetry exploitation in canonical forms, but it may hinder if the group is computationally hard to generate, as in highly symmetric graphs like strongly regular ones. This duality underscores the interplay: trivial automorphisms simplify direct comparisons, while expansive ones demand robust group computation to leverage for faster isomorphism resolution.[17][28] Historically, the connection traces to George Pólya's 1937 enumeration theorem, which uses group actions—precursors to modern automorphism computations—to count distinct graphs up to isomorphism. Pólya's method applies Burnside's lemma over the action of the symmetric group on potential edge sets, yielding generating functions whose coefficients give isomorphism class sizes. This framework influenced early isomorphism algorithms by emphasizing orbit counting under group actions, providing a combinatorial foundation for later algebraic approaches to Aut(G)-invariant forms.Algorithms for Computation

Computing the automorphism group of a graph typically involves backtrack search algorithms that explore possible permutations while pruning the search space using symmetries detected during the process. The Nauty algorithm, introduced by Brendan D. McKay in 1981, is a seminal backtrack-based method that computes generators for the automorphism group by constructing a canonical labeling of the graph.[29] It employs partition refinement to group vertices into equitable classes based on their structural roles, iteratively splitting partitions until they distinguish non-equivalent vertices or reveal automorphisms.[30] A core technique in Nauty is the individualization-refinement procedure, where a vertex from a non-trivial cell in the current partition is selected and "individualized" by assigning it a unique color, followed by refining the partition to propagate this distinction through the graph's structure. This process is repeated, building a partition nest that guides the backtrack search until a base of the group is found, allowing enumeration of automorphisms. The search prunes branches using the orbit-stabilizer theorem to avoid redundant explorations of equivalent configurations.[30] Once candidate generators are identified through backtracking, the Schreier-Sims algorithm is adapted to represent and process the permutation group efficiently, computing a base and strong generating set (BSGS) to determine the group's order and orbits. In implementations like Nauty and its successor Traces, a randomized variant of the Schreier method is used to manage the group elements, ensuring probabilistic completeness while handling large groups. Traces, developed as an extension in the 2010s by McKay and Adolfo Piperno, enhances Nauty's depth-first search with breadth-first strategies for certain subproblems, improving performance on dense graphs.[31][30] In the worst case, these backtrack algorithms exhibit exponential time complexity bounded by , reflecting the factorial number of potential permutations divided by the group order, though practical heuristics like early pruning and refined invariants make them efficient for graphs with up to several thousand vertices.[30]Applications and Tools

Uses in Graph Algorithms

Graph automorphisms play a key role in symmetry reduction techniques for graph algorithms, particularly in model checking and constraint satisfaction problems, where they enable orbit partitioning to significantly reduce the explored state space. In probabilistic model checking, automorphisms define permutations that preserve transition probabilities in models like discrete-time Markov chains, allowing states to be grouped into orbits—equivalence classes under the automorphism group—such that only one representative per orbit needs to be analyzed, reducing the state space from exponential size (for symmetric components each with local states) to a polynomial fraction like . This approach has been implemented using multi-terminal binary decision diagrams to efficiently compute and apply the reduction without loss of verification accuracy. Similarly, in constraint satisfaction problems modeled as graphs, automorphisms facilitate partitioning variables into symmetric orbits, pruning redundant search branches and accelerating solutions for symmetric instances like scheduling or circuit verification. Graph canonization, which produces a unique labeled representation invariant under automorphisms, is essential for efficient querying in graph databases and comparing chemical structures. In database querying, canonization normalizes graphs to enable fast isomorphism checks during subgraph matching or similarity searches, avoiding redundant computations over symmetric labelings. For chemical structure comparison, automorphism partitioning identifies symmetric atoms and bonds in molecular graphs, enabling polynomial-time canonical labeling via iterative refinement of vertex invariants based on extended connectivity and planar embedding properties, which has been applied to large structures like fullerenes with up to thousands of atoms. This ensures unique string representations (e.g., canonical SMILES) for database indexing and substructure retrieval in cheminformatics. In network analysis, graph automorphisms aid in detecting symmetric motifs—recurrent subgraphs with high automorphism groups—in social and biological networks, revealing structural redundancies that inform functional insights. For biological networks, such as protein interaction graphs, the symmetry compression method exploits automorphisms to compress symmetric subgraphs before enumeration, eliminating isomorphic duplicates and speeding up motif discovery by orders of magnitude in highly symmetric topologies, while preserving exact results through lossless decompression. In social networks, automorphisms help identify symmetric communities or roles by partitioning vertices into orbits, enabling scalable detection of motifs like balanced triads that indicate stable relationships. The automorphism group Aut(G) is central to enumeration algorithms via Pólya's enumeration theorem, which counts distinct graphs up to isomorphism by averaging the number of fixed colorings over group elements, applied to edge or vertex labelings to generate non-isomorphic structures. This method, originally developed for counting chemical compounds and graphs, uses the cycle index of Aut(G) to compute the number of unlabeled graphs with given properties, such as trees or regular graphs, avoiding exhaustive enumeration of the labeled graphs on vertices. Recent developments in cryptography leverage graph automorphisms for constructing secure hash functions based on symmetric graph structures, enhancing post-quantum resistance. In group-subgroup pair graphs, automorphisms induced by subgroup actions ensure vertex-transitive properties, allowing hash outputs invariant to symmetric traversals and reducing collision risks through normalized walks analyzed via group presentations. Similarly, structural hashing of directed graphs employs automorphism orbits for canonical node representations, guaranteeing that isomorphic subgraphs yield identical hashes while maintaining collision resistance, as proven for quotient graphs under symmetry.Software Implementations

Nauty and Traces form a widely used command-line suite for computing graph automorphisms and canonical labelings, particularly effective for both dense and sparse graphs. Developed by Brendan McKay and Adolfo Piperno, the tools employ partition refinement and backtrack search to determine the full automorphism group as a set of generators, supporting graphs with up to millions of vertices depending on memory availability, though practical limits around 100,000 vertices are common for dense instances on standard hardware.[32][31] SageMath integrates graph automorphism computation within its broader mathematical framework, returning the automorphism group as a permutation group object that leverages GAP for subsequent group-theoretic analysis. Theautomorphism_group() method refines an optional vertex partition to compute the largest equitable subgroup, supporting both undirected and directed graphs, and optionally uses external libraries like Bliss for faster execution on large inputs. This integration allows seamless exploration of group properties such as order, orbits, and generators directly in a Python-like environment.[33]

NetworkX, a Python library for graph analysis, provides automorphism support through its VF2++ algorithm implementation, which enables checking whether a proposed vertex mapping preserves graph structure and can thus verify individual automorphisms or generate partial mappings for self-isomorphisms. While it does not compute the full automorphism group natively, the isomorphism matchers facilitate automorphism detection by treating the graph against itself, making it suitable for smaller graphs or integration with custom backtrack routines.[34]

The GAP system, via its GRAPE package, specializes in permutation group computations tailored to graph automorphisms, representing Aut(G) as a subgroup of the symmetric group on vertices. GRAPE interfaces with Nauty or Bliss to efficiently calculate generators of the automorphism group, even for colored graphs, and supports isomorphism testing between graphs; for example, it handles the automorphism group of the Johnson graph J(4,2) with order 48. This makes GAP ideal for algebraic graph theory applications where group structure is central.[35]