Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cinder Cone and the Fantastic Lava Beds

View on Wikipedia

Cinder Cone is a cinder cone volcano in Lassen Volcanic National Park within the United States. It is located about 10 mi (16 km) northeast of Lassen Peak and provides an excellent view of Brokeoff Mountain, Lassen Peak, and Chaos Crags.

Key Information

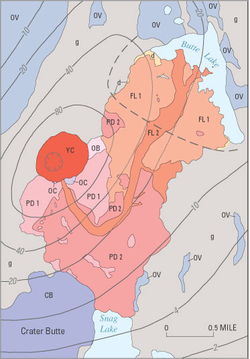

The cone was built to a height of 750 ft (230 m) above the surrounding area and spread ash over 30 sq mi (78 km2). Then, like many cinder cones, it was snuffed out when several basalt lava flows erupted from its base. These flows, called the Fantastic Lava Beds, spread northeast and southwest, and dammed creeks, first creating Snag Lake on the south and then Butte Lake to the north. Butte Lake is fed by water from Snag Lake seeping through the lava beds. Nobles Emigrant Trail goes around Snag Lake and follows the edge of the lava beds.

Its age has been controversial since the 1870s, when many people thought it was only a few decades old. Later, the cone and associated lava flows were thought to have formed about 1700 or during a 300-year- long series of eruptions ending in 1851. Recent studies by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) scientists, working in cooperation with the National Park Service to better understand volcanic hazards in the Lassen area, have firmly established that Cinder Cone was formed during two eruptions that occurred in the 1650s.

Geography

[edit]Cinder Cone lies in Lassen and Shasta counties, in Northern California, within the United States. Located 1.5 mi (2.4 km) southwest of Butte Lake and 2.2 mi (3.5 km) southeast of Prospect Peak[1] (which dwarfs Cinder Cone),[2] it is also sometimes referred to as Black Butte or Cinder Butte.[1] The volcano lies in the northeastern corner of Lassen Volcanic National Park.[3]

Nearby Snag Lake formed when lava known as the Painted Dunes flows dammed the Grassy Creek stream, which is fed by water from the central plateau of the national park area. Water from this lake feeds Butte Lake, located 2 mi (3.2 km) to the north. Butte Lake is the sole remaining fragment of a much larger body of water filled with lava during Cinder Cone's eruptive period. Diatomite sediment, formed from the aggregation of diatoms on the lake's floor, run along the edges of the Fantastic Lava Beds and mark the margins of this former lake.[4]

Description and geology

[edit]

Cinder Cone is a 700 ft (210 m)-high volcanic cone of loose scoria.[5] The youngest mafic volcano in the Lassen volcanic center,[6] it is surrounded by unvegetated block lava and has concentric craters at its summit,[5] which have diameters of 1,050 ft (320 m) and 590 ft (180 m).[3] Cinder Cone comprises five basaltic andesite and andesite lava flows, and it also has two cinder cone volcanoes, with two scoria cones, the first of which was mostly destroyed by lava flows from its base.[6] Cinder cone volcanoes are typically monogenetic, meaning that they only undergo one eruptive period before ceasing activity forever. These eruptions often consist of the ejection of tephra, though they may also generate lava flows, which often originate from vents near the base rather than the summit of the volcanic edifice.[7]

The summit of Cinder Cone has a crater with a double rim (photo), probably created by two different phases of one eruptive period.[8] The cone also has a widespread ash deposit identifiable for 8 to 10 mi (13 to 16 km) from the cone. Blocks of red, cemented scoria within the Painted Dunes lava flows (photo) are pieces of this earlier cone, which were carried away by the flowing lava.[4]

When Cinder Cone formed, the magma feeding the eruption changed composition, shifting from basaltic andesite to andesite before returning to basaltic andesite with increased titanium content. While basaltic andesites are volcanic rocks containing 53 to 57% silica, andesites are those containing 57 to 63% silica. The lava flows and scorias at the volcano closely resemble each other despite distinct chemical compositions, forming dark, fine-grained rocks, with a few visible crystals of the minerals olivine, plagioclase, and quartz.[4]

The early group of volcanic deposits at Cinder Cone, which have relatively little titanium, include older scoria cone, the Old Bench flow, the two Painted Dunes flows, and the lower part of the widespread ash layer. The second group, erupted later and comparatively rich in titanium, consists of the large, younger scoria cone, the upper part of the ash layer, and the two Fantastic Lava Beds flows. Radiocarbon dating places these occurrences between 1630 and 1670 CE.[4] At the Old Bench and Painted Dunes lava flows, the volcanic ash is brightly oxidized because it interacted with the lava flows when they were still hot. It shares its compositional group with the Fantastic Lava Beds flows, which represent the last flows erupted at Cinder Cone. Ultimately, the eruptive sequence at Cinder Cone took place over the course of several months.[4]

An unusual characteristic of the Fantastic Lava Beds is the presence of anomalous quartz crystal xenocrysts (foreign bodies in igneous rock). Geologists think that they were picked up from wall rocks by the lava as it moved toward the surface.[9]

Human history

[edit]Beginnings of a controversy

[edit]

After traveling through Northern California in the spring of 1851, two gold prospectors reported seeing an erupting volcano that "threw up fire to a terrible height"[4] and that they had walked for 10 mi (16 km) over rocks that burned through their boots.[10] This narrative complemented several accounts of activity at the volcano across 1850 and 1851, which all claimed to observe the eruptions from at least 40 mi (64 km) away.[5]

During the early 1870s, medical doctor and amateur scientist H. W. Harkness from San Francisco, California, visited the Cinder Cone area.[11] Intrigued by the "apparent youthfulness" of the area's volcanic landmarks, he observed several features to argue that Cinder Cone was only about 25 years old.[4] He presented his conclusions at a meeting of the California Academy of Sciences, and was contacted by Academy member Henry Chapman, who informed him of the gold prospector story. A number of other people reached out to Harkness about seeing volcanic activity in Lassen in about 1851, such as O. M. Wozencraft, which led Harkness to think that Cinder Cone had erupted recently.[4]

Though there were multiple reports of eruptive activity near Lassen in Northern California newspapers during the 1850s, the details remain inconsistent. The first such report, which was published in the August 21, 1850, edition of the Daily Pacific News (a San Francisco newspaper), cited an unnamed observer who claimed to have seen "burning lava still running down the sides" at Cinder Cone.[5] In 1859, the San Francisco Times published an article with testimony from Wozencraft and a companion in which they claimed to have seen flames in the sky from a volcanic eruption from a location west of the Lassen area. Receiving widespread attention, the article was widely reprinted, despite the fact that the account lacked specific dates or locations for their claims. Poking fun at Wozencraft's claims, the Shasta Republican wrote several times throughout April 1859 that "the Dr.'s imagination is far more active than any volcano in our County or State."[4] Harkness' 1875 report cites the date of Wozencraft's sighting to be the winter of 1850–1851.[4]

Early geologic studies

[edit]

The first geologist to study Cinder Cone was Joseph Diller.[12][13] One of the first USGS scientists to study volcanoes, Diller took careful notes on Cinder Cone and interviewed many Native Americans and European trappers and settlers inhabiting the Lassen region during 1850, none of whom remembered volcanic activity there. Aware of an "emigrant road" (the Nobles Emigrant Trail), which had been utilized by settlers coming to California in the early 1850s, that passes close to the base of Cinder Cone, he interviewed a number of people who "crossed the trail" in 1853.[4] They noted that a large, solitary willow bush (Salix scouleriana) near the summit of Cinder Cone had not been destroyed by any eruptive activity. The bush is still alive and has not been altered much since.[4]

Because the willow at the summit of Cinder Cone was already mature in 1853, Diller concluded it was extremely unlikely that an eruption could have occurred there in the winter of 1850.[4] He also noted that trees rooted in volcanic ash erupted from the cone were about 200 years old and that the oldest trees on related lava flows were about 150 years old. Diller believed he recognized two eruptive sequences, which each produced lava flows. However, he thought that only the older eruption was explosive, creating Cinder Cone and the ash deposits. In regard to the explosive eruption, he concluded that "Whatever may be the historical testimony as to the time of the eruption, the geologic evidence clearly demonstrates that it must have occurred long before the beginning of the present century" (before 1800).[4] Diller therefore speculated that the explosive eruption had occurred between about 1675 and 1700 and that the younger, quiet eruption was "certainly" sometime before 1840.[4]

On May 6, 1907, both Cinder Cone and Lassen Peak were designated national monuments, administered by the National Forest Service.[14] Cinder Cone's name was officially recognized by the United States Board on Geographic Names in 1927.[1] In the mid-1930s, USGS volcanologist R. H. Finch attempted to improve on Diller's work. On the basis of other studies done at Cinder Cone, Finch thought (1) that there had been at least five separate lava-flow events, as suggested by crude, experimental magnetic measurements;[15] (2) that the youngest lava flow was extruded in 1851, accepting Harkness' (1875) historical "evidence" and ignoring Diller's interviews and conclusions; and (3) that there had been at least two distinct explosive eruptions of the cone.[16] Using these assumptions and tree-ring measurements, Finch proposed a complex and detailed eruptive chronology for Cinder Cone that spanned nearly 300 years.[17] From measurements of the rings of one particular tree, which showed two periods of slow growth, he thought that the two explosive eruptions occurred in 1567 and 1666. He also concluded that the five lava flows were extruded in 1567, 1666, 1720, 1785, and 1851.[4]

New geologic studies

[edit]

After Finch published his work in 1937, few additional studies were done on volcanic hazards in the Lassen area. However, that changed after the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington. As a result, the USGS began reevaluating the risks posed by other potentially active volcanoes in the Cascade Range, including those in Lassen Volcanic National Park. Since that time, USGS scientists have been working in cooperation with the National Park Service to better understand volcanic hazards in the Lassen area. As part of this work, the history of Cinder Cone has been reexamined. Most of the features of Cinder Cone have changed little since Harkness first described them in the 1870s, but all of the assumptions on which Finch based his conclusions have now been shown to be incorrect.[4]

Through new field and laboratory work and by reinterpreting data from previous studies, USGS scientists have shown that the entire eruptive sequence at Cinder Cone represents a single continuous event. Because the orientation of the Earth's magnetic field in northern California during the 1850s is well known and is different from the remnant magnetizations at Cinder Cone, the lava flows there could not have been erupted in 1850 or 1852. Also, there are no discernible differences in the magnetic orientation recorded by any of the Cinder Cone lava flows, and so the flows had to be extruded during an interval of less than 50 years.[4]

Although paleomagnetic evidence can be used to rule out the 1850s as the age of Cinder Cone, it does not provide an actual age for its eruption. By measuring levels of carbon-14 in samples of wood from trees killed by the eruption of Cinder Cone, USGS scientists obtained a radiocarbon date for the eruption of between 1630 and 1670. Such a date is also consistent with the remnant magnetization preserved in the lava flows. The series of eruptions that produced the volcanic deposits at Cinder Cone were complex and are by no means completely understood. However, the new studies done by USGS scientists refute the purported accounts of an eruption in the early 1850s and confirm Diller's (1891, 1893) interpretation that Cinder Cone erupted in the latter half of the 17th century. They also suggest that the 1666 tree-ring date proposed by Finch (1937) for his "second" explosive eruption at Cinder Cone might actually date the entire eruptive sequence.[4][18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Cinder Cone". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 36.

- ^ a b Heiken 1978, p. 119.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Clynne, M. (May 24, 2005). Diggles, M. (ed.). "How Old is "Cinder Cone"?–Solving a Mystery in Lassen Volcanic National Park, California: Fact Sheet 023-00". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Harris 2005, p. 94.

- ^ a b "The Formation of Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park". California Volcano Observatory. United States Geological Survey. December 13, 2012. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 33.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 34.

- ^ James 1966, pp. 303–312.

- ^ Harris 2005, p. 95.

- ^ Harkness 1875, pp. 408–412.

- ^ Diller 1891.

- ^ Diller 1893, pp. 93–96.

- ^ "Cinder Cone and Lassen Peak National Monuments Celebrate 100th Birthday". National Park Service. February 28, 2015. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ Jones 1928, pp. 61–65.

- ^ Finch & Anderson 1930, pp. 245–273.

- ^ Finch 1937, pp. 140–146.

- ^ Sheppard et al. 2009, pp. 213–221.

Sources

[edit]- Diller, J. S. (1891). "A Late Volcanic Eruption in Northern California and Its Peculiar Lava". United States Geological Survey Bulletin. 79. United States Geological Survey.

- Diller, J. S. (1893). "Our Youngest Volcano". National Geographic. Vol. 4. National Geographic Partners. pp. 93–96.

- Finch, R. H. (1937). "A Tree Ring Calendar for Dating Volcanic Events at Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park, California". American Journal of Science. 33. American Journal of Science: 140–146. doi:10.2475/ajs.s5-33.194.140.

- Finch, R. H.; Anderson, C. A. (1930). "The Quartz Basalt Eruptions of Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park, California". University of California Publications in the Geological Sciences. 19. University of California: 245–273.

- Harris, S. L. (2005). Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes (Third ed.). Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. pp. 127–132. ISBN 0-87842-511-X.

- Harris, Ann G.; Tuttle,Esther; Tuttle, Sherwood D. (1997). Geology of National Parks (Fifth ed.). Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing. ISBN 0-7872-5353-7.

- Harkness, H. W. (1875). "A Recent Volcano in Plumas County". California Academy of Sciences Proceedings. 5. California Academy of Sciences: 408–412.

- Heiken, G. (June 1978). "Characteristics of Tephra From Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park, California". Bulletin of Volcanology. 41 (2). Springer Science+Business Media: 119–130. Bibcode:1978BVol...41..119H. doi:10.1007/bf02597025. S2CID 129896578.

- James, D. E. (March 1, 1966). "Geology and Rock Magnetism of Cinder Cone Lava Flows, Lassen Volcanic National Park, California". GSA Bulletin. 77 (3). Geological Society of America: 303–312. Bibcode:1966GSAB...77..303J. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1966)77[303:GARMOC]2.0.CO;2.

- Jones, A. E. (1928). "Magnetism of Cinder Cone Lava Flows. Lassen Volcanic National Park, California". Hawaiian Volcano Observatory Bulletin. 16: 61–65.

- Sheppard, P.R.; Ort, M.H.; Anderson, K.C.; Clynne, M.A.; May, E.M. (2009). "Multiple dendrochronological responses to the eruption of Cinder Cone, Lassen Volcanic National Park, CA". Dendrochronologia. 27: 213–221. doi:10.1016/j.dendro.2009.09.001.