Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Coercivity

View on Wikipedia

Coercivity, also called the magnetic coercivity, coercive field or coercive force, is a measure of the ability of a ferromagnetic material to withstand an external magnetic field without becoming demagnetized. Coercivity is usually measured in oersted or ampere/meter units and is denoted HC.

An analogous property in electrical engineering and materials science, electric coercivity, is the ability of a ferroelectric material to withstand an external electric field without becoming depolarized.

Ferromagnetic materials with high coercivity are called magnetically hard, and are used to make permanent magnets. Materials with low coercivity are said to be magnetically soft. The latter are used in transformer and inductor cores, recording heads, microwave devices, and magnetic shielding.

Definitions

[edit]

Coercivity in a ferromagnetic material is the intensity of the applied magnetic field (H field) required to demagnetize that material, after the magnetization of the sample has been driven to saturation by a strong field. This demagnetizing field is applied opposite to the original saturating field. There are however different definitions of coercivity, depending on what counts as 'demagnetized', thus the bare term "coercivity" may be ambiguous:

- The normal coercivity, HCn, is the H field required to reduce the magnetic flux (average B field inside the material) to zero.

- The intrinsic coercivity, HCi, is the H field required to reduce the magnetization (average M field inside the material) to zero.

- The remanence coercivity, HCr, is the H field required to reduce the remanence to zero, meaning that when the H field is finally returned to zero, then both B and M also fall to zero (the material reaches the origin in the hysteresis curve).[1]

The distinction between the normal and intrinsic coercivity is negligible in soft magnetic materials, however it can be significant in hard magnetic materials.[1] The strongest rare-earth magnets lose almost none of the magnetization at HCn.

Experimental determination

[edit]| Material | Coercivity (kA/m) |

|---|---|

| Supermalloy (16Fe:79Ni:5Mo) |

0.0002[2]: 131, 133 |

| Permalloy (Fe:4Ni) | 0.0008–0.08[3] |

| Iron filings (0.9995 wt) | 0.004–37.4[4][5] |

| Electrical steel (11Fe:Si) | 0.032–0.072[6] |

| Raw iron (1896) | 0.16[7] |

| Nickel (0.99 wt) | 0.056–23[5][8] |

| Ferrite magnet (ZnxFeNi1−xO3) |

1.2–16[9] |

| 2Fe:Co,[10] iron pole | 19[5] |

| Cobalt (0.99 wt) | 0.8–72[11] |

| Alnico | 30–150[12] |

| Disk drive recording medium (Cr:Co:Pt) |

140[13] |

| Neodymium magnet (NdFeB) | 800–950[14][15] |

| 12Fe:13Pt (Fe48Pt52) | ≥980[16] |

| ?(Dy,Nb,Ga(Co):2Nd:14Fe:B) | 2040–2090[17][18] |

| Samarium-cobalt magnet (2Sm:17Fe:3N; 10 K) |

<40–2800[19][20] |

| Samarium-cobalt magnet | 3200[21] |

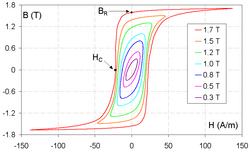

Typically the coercivity of a magnetic material is determined by measurement of the magnetic hysteresis loop, also called the magnetization curve, as illustrated in the figure above. The apparatus used to acquire the data is typically a vibrating-sample or alternating-gradient magnetometer. The applied field where the data line crosses zero is the coercivity. If an antiferromagnet is present in the sample, the coercivities measured in increasing and decreasing fields may be unequal as a result of the exchange bias effect.[citation needed]

The coercivity of a material depends on the time scale over which a magnetization curve is measured. The magnetization of a material measured at an applied reversed field which is nominally smaller than the coercivity may, over a long time scale, slowly relax to zero. Relaxation occurs when reversal of magnetization by domain wall motion is thermally activated and is dominated by magnetic viscosity.[22] The increasing value of coercivity at high frequencies is a serious obstacle to the increase of data rates in high-bandwidth magnetic recording, compounded by the fact that increased storage density typically requires a higher coercivity in the media.[citation needed]

Theory

[edit]At the coercive field, the vector component of the magnetization of a ferromagnet measured along the applied field direction is zero. There are two primary modes of magnetization reversal: single-domain rotation and domain wall motion. When the magnetization of a material reverses by rotation, the magnetization component along the applied field is zero because the vector points in a direction orthogonal to the applied field. When the magnetization reverses by domain wall motion, the net magnetization is small in every vector direction because the moments of all the individual domains sum to zero. Magnetization curves dominated by rotation and magnetocrystalline anisotropy are found in relatively perfect magnetic materials used in fundamental research.[23] Domain wall motion is a more important reversal mechanism in real engineering materials since defects like grain boundaries and impurities serve as nucleation sites for reversed-magnetization domains. The role of domain walls in determining coercivity is complicated since defects may pin domain walls in addition to nucleating them. The dynamics of domain walls in ferromagnets is similar to that of grain boundaries and plasticity in metallurgy since both domain walls and grain boundaries are planar defects.[citation needed]

Significance

[edit]As with any hysteretic process, the area inside the magnetization curve during one cycle represents the work that is performed on the material by the external field in reversing the magnetization, and is dissipated as heat. Common dissipative processes in magnetic materials include magnetostriction and domain wall motion. The coercivity is a measure of the degree of magnetic hysteresis and therefore characterizes the lossiness of soft magnetic materials for their common applications.

The saturation remanence and coercivity are figures of merit for hard magnets, although maximum energy product is also commonly quoted. The 1980s saw the development of rare-earth magnets with high energy products but undesirably low Curie temperatures. Since the 1990s new exchange spring hard magnets with high coercivities have been developed.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Giorgio Bertotti (21 May 1998). Hysteresis in Magnetism: For Physicists, Materials Scientists, and Engineers. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-08-053437-4.

- ^ Tumanski, S. (2011). Handbook of magnetic measurements. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 9781439829523.

- ^ M. A. Akhter-D. J. Mapps-Y. Q. Ma Tan-Amanda Petford-Long-R. Doole; Mapps; Ma Tan; Petford-Long; Doole (1997). "Thickness and grain-size dependence of the coercivity in permalloy thin films". Journal of Applied Physics. 81 (8): 4122. Bibcode:1997JAP....81.4122A. doi:10.1063/1.365100.

- ^ Calvert, J. B. (6 December 2003) [13 December 2002]. "Iron". mysite.du.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-09-15. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- ^ a b c "Magnetic Properties of Solids". Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ "timeout". Cartech.ides.com. Retrieved 22 November 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Thompson, Silvanus Phillips (1896). Dynamo-electric machinery. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ M. S. Miller-F. E. Stageberg-Y. M. Chow-K. Rook-L. A. Heuer; Stageberg; Chow; Rook; Heuer (1994). "Influence of rf magnetron sputtering conditions on the magnetic, crystalline, and electrical properties of thin nickel films". Journal of Applied Physics. 75 (10): 5779. Bibcode:1994JAP....75.5779M. doi:10.1063/1.355560.

- ^ Zhenghong Qian; Geng Wang; Sivertsen, J.M.; Judy, J.H. (1997). "Ni Zn ferrite thin films prepared by Facing Target Sputtering". IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 33 (5): 3748–3750. Bibcode:1997ITM....33.3748Q. doi:10.1109/20.619559.

- ^ Orloff, Jon (2017-12-19). Handbook of Charged Particle Optics, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420045550. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Luo, Hongmei; Wang, Donghai; He, Jibao; Lu, Yunfeng (2005). "Magnetic Cobalt Nanowire Thin Films". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 109 (5): 1919–22. doi:10.1021/jp045554t. PMID 16851175.

- ^ "Cast ALNICO Permanent Magnets" (PDF). Arnold Magnetic Technologies. Retrieved 4 November 2023.

- ^ Yang, M.M.; Lambert, S.E.; Howard, J.K.; Hwang, C. (1991). "Laminated CoPt Cr/Cr films for low noise longitudinal recording". IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 27 (6): 5052–5054. Bibcode:1991ITM....27.5052Y. doi:10.1109/20.278737.

- ^ C. D. Fuerst-E. G. Brewer; Brewer (1993). "High-remanence rapidly solidified Nd-Fe-B: Die-upset magnets (invited)". Journal of Applied Physics. 73 (10): 5751. Bibcode:1993JAP....73.5751F. doi:10.1063/1.353563.

- ^ "WONDERMAGNET.COM - NdFeB Magnets, Magnet Wire, Books, Weird Science, Needful Things". Wondermagnet.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Chen & Nikles 2002

- ^ Bai, G.; Gao, R.W.; Sun, Y.; Han, G.B.; Wang, B. (January 2007). "Study of high-coercivity sintered NdFeB magnets". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 308 (1): 20–23. Bibcode:2007JMMM..308...20B. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.04.029.

- ^ Jiang, H.; Evans, J.; O’Shea, M.J.; Du, Jianhua (2001). "Hard magnetic properties of rapidly annealed NdFeB thin films on Nb and V buffer layers". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 224 (3): 233–240. Bibcode:2001JMMM..224..233J. doi:10.1016/S0304-8853(01)00017-8.

- ^ Nakamura, H.; Kurihara, K.; Tatsuki, T.; Sugimoto, S.; Okada, M.; Homma, M. (October 1992). "Phase Changes and Magnetic Properties of Sm 2 Fe 17 N x Alloys Heat-Treated in Hydrogen". IEEE Translation Journal on Magnetics in Japan. 7 (10): 798–804. doi:10.1109/TJMJ.1992.4565502.

- ^ Rani, R.; Hegde, H.; Navarathna, A.; Cadieu, F. J. (15 May 1993). "High coercivity Sm 2 Fe 17 N x and related phases in sputtered film samples". Journal of Applied Physics. 73 (10): 6023–6025. Bibcode:1993JAP....73.6023R. doi:10.1063/1.353457. INIST 4841321.

- ^ de Campos, M. F.; Landgraf, F. J. G.; Saito, N. H.; Romero, S. A.; Neiva, A. C.; Missell, F. P.; de Morais, E.; Gama, S.; Obrucheva, E. V.; Jalnin, B. V. (1998-07-01). "Chemical composition and coercivity of SmCo5 magnets". Journal of Applied Physics. 84 (1): 368–373. Bibcode:1998JAP....84..368D. doi:10.1063/1.368075. ISSN 0021-8979.

- ^ Gaunt 1986

- ^ Genish et al. 2004

- ^ Kneller & Hawig 1991

- Chen, Min; Nikles, David E. (2002). "Synthesis, self-assembly, and magnetic properties of FexCoyPt100-x-y nanoparticles". Nano Letters. 2 (3): 211–214. Bibcode:2002NanoL...2..211C. doi:10.1021/nl015649w.

- Gaunt, P. (1986). "Magnetic viscosity and thermal activation energy". Journal of Applied Physics. 59 (12): 4129–4132. Bibcode:1986JAP....59.4129G. doi:10.1063/1.336671.

- Genish, Isaschar; Kats, Yevgeny; Klein, Lior; Reiner, James W.; Beasley, M. R. (2004). "Local measurements of magnetization reversal in thin films of SrRuO3". Physica Status Solidi C. 1 (12): 3440–3442. Bibcode:2004PSSCR...1.3440G. doi:10.1002/pssc.200405476.

- Kneller, E. F.; Hawig, R. (1991). "The exchange-spring magnet: a new material principle for permanent magnets". IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 27 (4): 3588–3600. Bibcode:1991ITM....27.3588K. doi:10.1109/20.102931.

- Livingston, J. D. (1981). "A review of coercivity mechanisms". Journal of Applied Physics. 52 (3): 2541–2545. Bibcode:1981JAP....52.2544L. doi:10.1063/1.328996.

External links

[edit]- Magnetization reversal applet (coherent rotation)

- For a table of coercivities of various magnetic recording media, see "Degaussing Data Storage Tape Magnetic Media" (PDF), at fujifilmusa.com.

Coercivity

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Coercivity, denoted as , is the magnetic field strength required to reduce the magnetic flux density of a ferromagnetic material to zero after it has been saturated.[7] This parameter quantifies the material's resistance to demagnetization and is a fundamental characteristic in the study of magnetic hysteresis.[1] Coercivity is expressed in amperes per meter (A/m) in the SI unit system or oersteds (Oe) in the cgs system, with the approximate conversion Oe A/m.[8] A distinction exists between normal coercivity ( or ), applicable to multidomain materials and defined as the field that reduces the average magnetic flux density to zero, and intrinsic coercivity (), relevant for single-domain particles and defined as the field that reduces the intrinsic magnetization to zero.[9][10] Early measurements of magnetic hysteresis were conducted by James Alfred Ewing in the 1890s.[11]Related Concepts

Remanence, often denoted as or , represents the residual magnetization in a ferromagnetic material after the external magnetic field is removed following saturation. This property is intrinsically linked to coercivity, as both are extracted from the second quadrant of the hysteresis loop: remanence is the magnetization value at zero applied field (), while coercivity is the reverse field strength required to drive the magnetization to zero. In materials with high remanence relative to saturation, the hysteresis loop exhibits greater "squareness," indicating efficient retention of magnetic state, which complements high coercivity in permanent magnet applications.[12] Saturation magnetization, , denotes the maximum achievable magnetization when all magnetic moments in the material are fully aligned by a sufficiently strong applied field. Unlike coercivity, which measures the resistance to demagnetization from this saturated state, sets the upper limit on the material's magnetic strength and is a fundamental intrinsic property influenced by composition and temperature. The contrast is evident in the hysteresis loop, where coercivity defines the field needed to nullify magnetization starting from , highlighting how high-coercivity materials maintain alignment against opposing fields while approaching their saturation limit.[13] Magnetic susceptibility and permeability quantify a material's response to applied fields, with relating induction to field strength. Low-coercivity (soft) magnetic materials feature high and (often ), enabling rapid and efficient magnetization for applications like transformers, whereas high-coercivity (hard) materials exhibit low and (typically ), prioritizing stability over ease of magnetization. This distinction arises because elevated coercivity suppresses reversible domain wall motion and moment rotation, reducing overall susceptibility.[14] Beyond standard coercivity , remanent coercivity specifically denotes the reverse field applied to reduce the remanence to zero after initial saturation and field removal. It is determined from the demagnetization curve as the field strength at which the magnetization reaches zero when starting from the remanent state (H=0, M=M_r). This parameter is particularly relevant for evaluating demagnetization resistance in permanent magnets, often exceeding in hard materials due to irreversible processes.[15] Illustrative examples underscore these relations: soft magnets like commercial iron exhibit low coercivity ( kA/m, typically 0.2–0.7 kA/m) and high permeability, ideal for electromagnetic cores in transformers where minimal energy loss during cycling is essential. In contrast, hard magnets such as NdFeB alloys display high coercivity ( kA/m, e.g., up to 1115 kA/m in high-grade variants) and substantial remanence, enabling their use in compact permanent magnets for motors and generators.[16][15]Measurement

Experimental Techniques

The primary experimental technique for determining coercivity involves generating a hysteresis loop using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM), which measures the magnetization as a function of applied magnetic field . In this method, the sample is first saturated by applying a sufficiently strong magnetic field in one direction to align all magnetic moments, typically exceeding the saturation field . The field is then gradually reduced to zero, resulting in remanent magnetization , followed by the application of a reverse field until the magnetization crosses zero, at which point the applied field value corresponds to the coercivity . This process traces the full hysteresis loop, from which is extracted as the reverse field magnitude where in the second quadrant. VSM operates by vibrating the sample in a uniform magnetic field, inducing a voltage in pickup coils proportional to the sample's magnetic moment via Faraday's law of induction, enabling precise measurements over a wide range of fields up to 7 T and temperatures from cryogenic to elevated levels.[17] Alternative techniques include superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometry, particularly suited for low-field measurements and small samples where high sensitivity (down to emu) is required, such as in nanomaterials with coercivities below 1 kA/m. SQUIDs detect minute magnetic fluxes using superconducting loops, allowing hysteresis loops to be traced similarly to VSM but with superior resolution for weak signals at fields as low as 0.001 T. For industrial applications, hysteresisgraphs provide rapid, automated testing of bulk permanent magnets, applying pulsed or cyclic fields to generate loops and determine in seconds, often up to 2.5 T, without the need for sample vibration. These instruments are optimized for quality control, handling larger samples like magnet blocks.[18][19] Coercivity exhibits time and frequency dependence due to magnetic viscosity, a thermally activated process where domain walls or moments relax slowly, leading to higher values at faster measurement rates. In DC measurements, which use quasi-static field sweeps (e.g., 1-10 Oe/s), reflects equilibrium conditions, whereas AC measurements at frequencies of 1-1000 Hz or rapid sweeps introduce dynamic effects, increasing by 10-50% in soft materials like ferrites, as the system cannot fully relax. For instance, in NdFeB magnets, rises with sweep rate according to , where is the viscosity coefficient.[20] Sample preparation is crucial for accurate determination, beginning with demagnetization to eliminate prior remanence, typically via alternating field (AF) cycling in a tumbler or thermal treatment above the Curie temperature, followed by cooling in zero field. Samples are then mounted on a non-magnetic holder (e.g., quartz rod) aligned with the field axis, ensuring minimal shape anisotropy. Field calibration involves verifying the electromagnet or superconducting coil using a reference standard like a proton NMR probe or Hall sensor, achieving accuracy better than 0.1%. Powders may require epoxy encapsulation to prevent reorientation during vibration.[21]| Material | Typical Coercivity () | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Permalloy (Ni-Fe) | ~11 A/m | Soft magnetic alloy; bulk value for high-permeability grades.[22] |

| Alnico (cast) | 50-150 kA/m | Permanent magnet; varies by grade (e.g., Alnico 5). |

| SmCo (1:5 type) | 500-2000 kA/m | High-temperature permanent magnet; annealed ribbons.[23] |

| FePt nanoparticles | ~5 MA/m | L1₀-ordered, ~5-10 nm size; typical for chemically synthesized nanoparticles.[24] |

Hysteresis Loop Analysis

The hysteresis loop in ferromagnetic materials graphically represents the relationship between the applied magnetic field strength and the magnetization , illustrating the material's nonlinear and history-dependent response during magnetization reversal. The major hysteresis loop is obtained by cycling the field from positive saturation, where reaches its maximum value , through zero field to negative saturation, enclosing an area that quantifies energy dissipation. Key points on the loop include saturation magnetization at high fields, remanent magnetization (briefly referenced as the residual at ), and coercivity , marking the reverse field needed to reduce to zero. Minor loops, formed by incomplete field cycles, reveal dynamic effects such as loop widening under time-varying fields, providing insights into reversible and irreversible processes without reaching saturation.[26][27] Coercivity is extracted from the major loop as the value of where the demagnetization curve intersects the axis, directly measuring the field's resistance to domain reversal. This intrinsic coercivity applies specifically to the - curve and differs from the normal coercivity on the - loop, where demagnetizing fields influence the intersection; high-field extrapolations distinguish by extending the linear portion of the second quadrant to , avoiding artifacts from sample shape. For accurate determination, loops are measured under quasi-static conditions to minimize dynamic broadening.[26][28][29] The area of the hysteresis loop correlates with coercivity through its representation of energy dissipation per cycle, as higher typically widens the loop, increasing the enclosed area and thus hysteresis loss. The energy loss per unit volume for a closed loop in the - plane is given by the line integral , which quantifies the work done by the field against irreversible domain wall motion and pinning. To derive this, consider the magnetic energy density supplied by the external field during a small field change : the incremental work is , where is the permeability of free space (in SI units; often omitted in cgs for simplicity). Over a complete cycle, the term vanishes due to the closed path, leaving , or simply in normalized units. This area scales with in simple models, linking coercivity to practical losses in devices like transformers.[30][31][32] The temperature dependence of coercivity follows an empirical form , where is the Curie temperature and for many ferromagnets, reflecting the softening of anisotropy and exchange interactions with rising temperature. This relation, akin to Kneller's law for permanent magnets, predicts a near-linear drop near but accelerates toward , with deviations observed in nanostructured materials due to surface effects. Experimental loops at elevated temperatures show shrinking and loop areas, confirming the model's utility for thermal stability assessments.[33][34] At higher frequencies, hysteresis loops exhibit broadening, with an apparent increase in due to eddy current shielding and viscous domain wall motion, altering the loop shape from quasi-static ideals. As frequency rises, minor loops expand in width and area, dissipating more energy via dynamic losses, though the intrinsic remains tied to static properties. This effect is pronounced in conductive ferromagnets, where skin depth limits field penetration, leading to tilted loops at gigahertz ranges.[35][36] Software tools employing the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) equation simulate hysteresis loops for fitting experimental data, capturing precessional dynamics without full microscopic details. These micromagnetic codes, such as OOMMF or MuMax3, model extraction by solving for discretized spins, enabling parameter optimization like anisotropy constants from loop shapes.[37][38]Theoretical Foundations

Classical Mechanisms

Classical mechanisms of coercivity in ferromagnetic materials primarily arise from processes at the domain level, where the reversal of magnetization is governed by the motion of domain walls and the coherent rotation of magnetization within single domains. These foundational theories, developed in the mid-20th century, explain how microstructural features and applied fields influence the field required to reverse the magnetization direction. In soft magnetic materials, low coercivity stems from facile domain wall motion, while hard magnets exhibit high coercivity due to impediments to this motion or rotation. One key classical mechanism is the pinning of domain walls by defects such as inclusions, grain boundaries, or dislocations during magnetization reversal. Domain walls, transitional regions between magnetic domains, possess an energy associated with exchange and anisotropy contributions, and their width is typically on the order of tens of nanometers. The pinning field , representing the coercive field contribution from this mechanism, is given by the expression for the maximum field to unpin a wall from a defect: where is the permeability of free space and is the saturation magnetization. This formula derives from the balance between the Zeeman energy gained by wall motion and the increase in wall energy due to pinning sites, as originally conceptualized in early models of heterogeneous pinning. In materials with abundant defects, such as polycrystalline alloys, this pinning dominates, leading to higher coercivity as the density of pinning sites increases. In contrast, for single-domain particles where domain walls are absent, coercivity arises from the coherent rotation of the magnetization vector, as described by the Stoner-Wohlfarth model. This model assumes uniform rotation of the magnetization in a uniaxial anisotropic particle under an applied field at angle to the easy axis. The coercivity for field alignment along the easy axis () is , where is the anisotropy constant. For oblique fields, it exhibits angular dependence, such as near the easy axis, reflecting the astroid-shaped switching curve in the hysteresis loop. This mechanism is particularly relevant for fine particles or elongated shapes where single-domain states minimize magnetostatic energy, yielding remanence ratios up to 0.87 for aligned particles. Coercivity mechanisms differ markedly between soft and hard magnets: in soft materials, reversal initiates via easy nucleation of reverse domains at low fields due to weak pinning or low anisotropy, resulting in kA/m; in hard magnets, strong pinning at defects suppresses wall motion post-nucleation, sustaining high kA/m until the field overcomes the barriers. This nucleation-pinning duality resolves historical debates on reversal processes, with nucleation controlling initial reversal in soft phases and pinning dictating overall coercivity in composites or hard alloys. Microstructure profoundly influences these mechanisms, with grain size playing a central role akin to the Hall-Petch relation in mechanical properties. In polycrystalline magnets, smaller grains increase grain boundary density, enhancing pinning and thus coercivity via , as finer structures reduce domain sizes and elevate reversal barriers. Inclusions further amplify pinning by creating local energy variations, though excessive defects can promote nucleation sites, trading off coercivity in optimized alloys like NdFeB. Temperature effects introduce thermal activation over energy barriers in pinning and rotation processes, following the Arrhenius law for the relaxation rate or viscosity , where is Boltzmann's constant and is temperature. This leads to a softening of coercivity at elevated temperatures, as thermal energy aids wall depinning or rotational switching, with typically scaling with anisotropy volume . In permanent magnets, this activation explains the exponential decay of , limiting operational temperatures unless high materials are used.Micromagnetic and Advanced Models

Micromagnetic theory provides a continuum framework for modeling magnetization processes at the nanoscale, incorporating exchange interactions, magnetostatic fields, and anisotropy to predict coercivity in inhomogeneous systems. The dynamics of magnetization reversal are governed by the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) equation, which describes the precessional and damping motion of magnetic moments under an effective field: where is the magnetization vector, is the gyromagnetic ratio, is the effective field, is the Gilbert damping parameter, and is the saturation magnetization. This equation enables numerical simulations of domain wall motion and nucleation events that determine the coercive field in complex microstructures.[39][40] Finite element methods extend these simulations to three-dimensional geometries, discretizing the material into tetrahedral meshes to capture grain boundaries and defects in polycrystalline magnets. The Object Oriented MicroMagnetic Framework (OOMMF), developed by NIST, is a widely used finite-difference solver adapted for such 3D modeling, allowing computation of variations due to local exchange and demagnetization effects in polycrystalline structures like sintered NdFeB alloys. These simulations reveal how grain size distributions below 100 nm can enhance by reducing reversal nucleation sites.[41][42] In core-shell nanoparticles, exchange bias arises from interfacial coupling between ferromagnetic cores and antiferromagnetic shells, leading to shifted hysteresis loops and increased coercivity. Antiferromagnetic coupling pins the interface spins during reversal, enhancing by up to 50% compared to uncoupled particles, as the uncompensated spins in the shell resist domain expansion. This effect is prominent in systems like FePt@CoO, where Monte Carlo and micromagnetic models confirm the bias field scales with shell thickness and Néel temperature.[43][44] Magnetic viscosity introduces time dependence to coercivity through thermal activation over distributed pinning sites, modeled as , where is the athermal coercivity, is the viscosity coefficient, is observation time, and is a microscopic attempt time. This logarithmic decay reflects a spectrum of energy barriers from defects, causing gradual magnetization relaxation and reducing effective over seconds to hours in ferromagnets like NdFeB. Micromagnetic simulations incorporating stochastic LLG terms validate this by showing pinning site density correlates with values around 10-50 Oe per decade in time.[45][46] Anisotropy contributions significantly modulate , with magnetocrystalline anisotropy characterized by the constant dictating easy-axis alignment in cubic crystals like Fe, where for coherent rotation. Shape anisotropy from demagnetization fields favors elongation along the magnetization direction, increasing in nanorods by factors of 2-5 relative to spheres. Stress-induced anisotropy, via magnetoelastic coupling, further tunes ; tensile stress along the easy axis can enhance it by 2400% in uniaxial materials like CoFeB through perturbation of crystal fields. These effects combine in micromagnetic models to predict in textured alloys.[47] Validation of these models against experiments demonstrates their predictive power, particularly in nanostructured alloys where simulations post-2010 have shown enhancements of 20-50% in L1_0-FeNi through grain refinement to 10-20 nm, matching observed values in chemically synthesized composites. In SmCo 1:7 magnets, finite element simulations correlate cellular microstructures with kOe, aligning with measured hysteresis in hot-deformed samples and highlighting the role of boundary phases in pinning.[48][49]Applications and Significance

Material Classification

Magnetic materials are classified based on their coercivity (H_c), which determines their suitability for specific applications by balancing ease of magnetization, energy losses, and resistance to demagnetization.[15] This classification often considers the ratio of H_c to saturation magnetization (M_s), as a low H_c/M_s favors soft materials for efficient flux conduction, while a high ratio enables hard materials to maintain strong fields.[50] The categories—soft, semi-hard, and hard—link theoretical reversal mechanisms, such as domain wall motion in soft materials versus coherent rotation in hard ones, to practical design trade-offs like permeability versus stability.[51] Soft magnetic materials exhibit very low coercivity, typically H_c < 1,000 A/m, enabling easy magnetization and demagnetization with minimal hysteresis losses, ideal for transformer cores and inductors.[15] For example, silicon-iron (Si-Fe) alloys, such as grain-oriented electrical steel, achieve H_c values of around 4–20 A/m, offering high permeability (up to 30,000) but requiring careful design to balance electrical resistivity and core losses.[15] These materials prioritize low H_c to maximize efficiency in alternating current devices, though high permeability can introduce trade-offs like increased magnetostriction. Semi-hard magnetic materials have intermediate coercivity, ranging from 1,000 to 50,000 A/m, providing a balance for applications requiring moderate retention of magnetization without excessive losses.[51] Ferrites, such as barium or strontium variants used in magnetic recording media, exemplify this class with H_c around 20,000–200,000 A/m, allowing data writing via moderate fields while retaining signals against thermal fluctuations.[52] Design implications include optimizing particle size and orientation to control reversal via domain wall pinning, enhancing stability in storage technologies.[53] Hard magnetic materials, or permanent magnets, possess high coercivity exceeding 100 kA/m, resisting demagnetization under operational fields and enabling compact, high-energy designs.[54] Neodymium-iron-boron (Nd₂Fe₁₄B) represents a benchmark with intrinsic coercivity H_{ci} ≈ 955 kA/m, achieving a maximum energy product (BH)_max up to 400 kJ/m³ through strong uniaxial anisotropy that promotes coherent reversal.[15] In design, this class emphasizes the (BH)_max figure of merit to maximize torque or force in motors and generators, with H_c ensuring reliability against demagnetizing influences like temperature or stray fields.[55] The classification has evolved significantly, originating with Alnico alloys in the 1940s (H_c ≈ 50–150 kA/m) that relied on shape anisotropy for moderate performance, transitioning to rare-earth magnets in the 1980s like Nd₂Fe₁₄B, which boosted H_c via enhanced magnetocrystalline anisotropy for superior energy density.[56] Alloying with rare-earth elements, such as neodymium, increases the anisotropy constant (K₁ > 4 MJ/m³ in Nd₂Fe₁₄B), elevating H_c by strengthening exchange interactions and hindering domain nucleation.[57] Recent 2020s developments include exchange-spring composites, such as Ni-Cu-Zn ferrite-hard phase systems, achieving H_c ≈ 200 kA/m by coupling soft and hard phases for improved coercivity without rare-earth dependency. As of 2024, grain boundary diffusion techniques have further enhanced H_c temperature stability in NdFeB magnets for high-temperature applications like electric vehicles.[58][59]| Class | H_c Range (A/m) | Representative Examples | Key Design Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soft | < 1000 | Si-Fe (20 A/m), Ni-Fe permalloy (0.4 A/m) | Low-loss cores; high permeability trade-off |

| Semi-hard | 1000–50,000 | Ferrites for recording (20,000–200,000 A/m), Vicalloy (20,000 A/m) | Intermediate stability for data retention |

| Hard | > 100,000 | Nd₂Fe₁₄B (955,000 A/m), exchange-spring Fe-Ni-Cu composites (200,000 A/m) | Permanent magnets; high (BH)_max for compact devices |