Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Exponential decay

View on Wikipedia

A quantity is subject to exponential decay if it decreases at a rate proportional to its current value. Symbolically, this process can be expressed by the following differential equation, where N is the quantity and λ (lambda) is a positive rate called the exponential decay constant, disintegration constant,[1] rate constant,[2] or transformation constant:[3]

The solution to this equation (see derivation below) is:

where N(t) is the quantity at time t, N0 = N(0) is the initial quantity, that is, the quantity at time t = 0.

Measuring rates of decay

[edit]Mean lifetime

[edit]If the decaying quantity, N(t), is the number of discrete elements in a certain set, it is possible to compute the average length of time that an element remains in the set. This is called the mean lifetime (or simply the lifetime), where the exponential time constant, , relates to the decay rate constant, λ, in the following way:

The mean lifetime can be looked at as a "scaling time", because the exponential decay equation can be written in terms of the mean lifetime, , instead of the decay constant, λ:

and that is the time at which the population of the assembly is reduced to 1⁄e ≈ 0.367879441 times its initial value. This is equivalent to ≈ 1.442695 half-lives.

For example, if the initial population of the assembly, N(0), is 1000, then the population at time , , is 368.

A very similar equation will be seen below, which arises when the base of the exponential is chosen to be 2, rather than e. In that case the scaling time is the "half-life".

Half-life

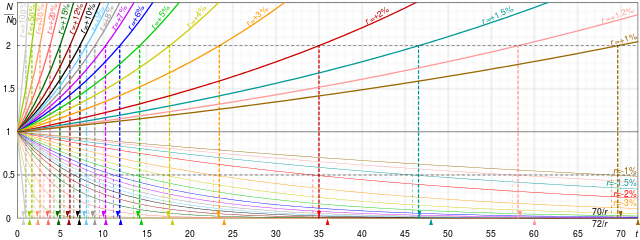

[edit]A more intuitive characteristic of exponential decay for many people is the time required for the decaying quantity to fall to one half of its initial value. (If N(t) is discrete, then this is the median life-time rather than the mean life-time.) This time is called the half-life, and often denoted by the symbol t1/2. The half-life can be written in terms of the decay constant, or the mean lifetime, as:

When this expression is inserted for in the exponential equation above, and ln 2 is absorbed into the base, this equation becomes:

Thus, the amount of material left is 2−1 = 1/2 raised to the (whole or fractional) number of half-lives that have passed. Thus, after 3 half-lives there will be 1/23 = 1/8 of the original material left.

Therefore, the mean lifetime is equal to the half-life divided by the natural log of 2, or:

For example, polonium-210 has a half-life of 138 days, and a mean lifetime of 200 days.

Solution of the differential equation

[edit]The equation that describes exponential decay is

or, by rearranging (applying the technique called separation of variables),

Integrating, we have

where C is the constant of integration, and hence

where the final substitution, N0 = eC, is obtained by evaluating the equation at t = 0, as N0 is defined as being the quantity at t = 0.

This is the form of the equation that is most commonly used to describe exponential decay. Any one of decay constant, mean lifetime, or half-life is sufficient to characterise the decay. The notation λ for the decay constant is a remnant of the usual notation for an eigenvalue. In this case, λ is the eigenvalue of the negative of the differential operator with N(t) as the corresponding eigenfunction.

Derivation of the mean lifetime

[edit]Given an assembly of elements, the number of which decreases ultimately to zero, the mean lifetime, , (also called simply the lifetime) is the expected value of the amount of time before an object is removed from the assembly. Specifically, if the individual lifetime of an element of the assembly is the time elapsed between some reference time and the removal of that element from the assembly, the mean lifetime is the arithmetic mean of the individual lifetimes.

Starting from the population formula

first let c be the normalizing factor to convert to a probability density function:

or, on rearranging,

Exponential decay is a scalar multiple of the exponential distribution (i.e. the individual lifetime of each object is exponentially distributed), which has a well-known expected value. We can compute it here using integration by parts.

Decay by two or more processes

[edit]A quantity may decay via two or more different processes simultaneously. In general, these processes (often called "decay modes", "decay channels", "decay routes" etc.) have different probabilities of occurring, and thus occur at different rates with different half-lives, in parallel. The total decay rate of the quantity N is given by the sum of the decay routes; thus, in the case of two processes:

The solution to this equation is given in the previous section, where the sum of is treated as a new total decay constant .

Partial mean life associated with individual processes is by definition the multiplicative inverse of corresponding partial decay constant: . A combined can be given in terms of s:

Since half-lives differ from mean life by a constant factor, the same equation holds in terms of the two corresponding half-lives:

where is the combined or total half-life for the process, and are so-named partial half-lives of corresponding processes. Terms "partial half-life" and "partial mean life" denote quantities derived from a decay constant as if the given decay mode were the only decay mode for the quantity. The term "partial half-life" is misleading, because it cannot be measured as a time interval for which a certain quantity is halved.

In terms of separate decay constants, the total half-life can be shown to be

For a decay by three simultaneous exponential processes the total half-life can be computed as above:

Decay series / coupled decay

[edit]In nuclear science and pharmacokinetics, the agent of interest might be situated in a decay chain, where the accumulation is governed by exponential decay of a source agent, while the agent of interest itself decays by means of an exponential process.

These systems are solved using the Bateman equation.

In the pharmacology setting, some ingested substances might be absorbed into the body by a process reasonably modeled as exponential decay, or might be deliberately formulated to have such a release profile.

Applications and examples

[edit]Exponential decay occurs in a wide variety of situations. Most of these fall into the domain of the natural sciences.

Many decay processes that are often treated as exponential, are really only exponential so long as the sample is large and the law of large numbers holds. For small samples, a more general analysis is necessary, accounting for a Poisson process.

Natural sciences

[edit]- Chemical reactions: The rates of certain types of chemical reactions depend on the concentration of one or another reactant. Reactions whose rate depends only on the concentration of one reactant (known as first-order reactions) consequently follow exponential decay. For instance, many enzyme-catalyzed reactions behave this way.

- Electrostatics: In a RC circuit, the electric charge (or, equivalently, the potential) contained in a capacitor (capacitance C) discharges through a constant external load (resistance R) with exponential decay and similarly charges with the mirror image of exponential decay (when the capacitor is charged from a constant voltage source though a constant resistance). The exponential time-constant for the process is so the half-life is The same equations can be applied to the dual of current in an inductor.

- Furthermore, the particular case of a capacitor or inductor changing through several parallel resistors makes an interesting example of multiple decay processes, with each resistor representing a separate process. In fact, the expression for the equivalent resistance of two resistors in parallel mirrors the equation for the half-life with two decay processes.

- Geophysics: Atmospheric pressure decreases approximately exponentially with increasing height above sea level, at a rate of about 12% per 1000m.[citation needed]

- Heat transfer: If an object at one temperature is exposed to a medium of another temperature, the temperature difference between the object and the medium follows exponential decay (in the limit of slow processes; equivalent to "good" heat conduction inside the object, so that its temperature remains relatively uniform through its volume). See also Newton's law of cooling.

- Luminescence: After excitation, the emission intensity – which is proportional to the number of excited atoms or molecules – of a luminescent material decays exponentially. Depending on the number of mechanisms involved, the decay can be mono- or multi-exponential.

- Pharmacology and toxicology: It is found that many administered substances are distributed and metabolized (see clearance) according to exponential decay patterns. The biological half-lives "alpha half-life" and "beta half-life" of a substance measure how quickly a substance is distributed and eliminated.

- Physical optics: The intensity of electromagnetic radiation such as light or X-rays or gamma rays in an absorbent medium, follows an exponential decrease with distance into the absorbing medium. This is known as the Beer-Lambert law.

- Radioactivity: In a sample of a radionuclide that undergoes radioactive decay to a different state, the number of atoms in the original state follows exponential decay as long as the remaining number of atoms is large. The decay product is termed a radiogenic nuclide.

- Thermoelectricity: The decline in resistance of a Negative Temperature Coefficient Thermistor as temperature is increased.

- Vibrations: Some vibrations may decay exponentially; this characteristic is often found in damped mechanical oscillators, and used in creating ADSR envelopes in synthesizers. An overdamped system will simply return to equilibrium via an exponential decay.

- Beer froth: Arnd Leike, of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, won an Ig Nobel Prize for demonstrating that beer froth obeys the law of exponential decay.[4]

Social sciences

[edit]- Finance: a retirement fund will decay exponentially being subject to discrete payout amounts, usually monthly, and an input subject to a continuous interest rate. A differential equation dA/dt = input − output can be written and solved to find the time to reach any amount A, remaining in the fund.

- In simple glottochronology, the (debatable) assumption of a constant decay rate in languages allows one to estimate the age of single languages. (To compute the time of split between two languages requires additional assumptions, independent of exponential decay).

Computer science

[edit]- The core routing protocol on the Internet, BGP, has to maintain a routing table in order to remember the paths a packet can be deviated to. When one of these paths repeatedly changes its state from available to not available (and vice versa), the BGP router controlling that path has to repeatedly add and remove the path record from its routing table (flaps the path), thus spending local resources such as CPU and RAM and, even more, broadcasting useless information to peer routers. To prevent this undesired behavior, an algorithm named route flapping damping assigns each route a weight that gets bigger each time the route changes its state and decays exponentially with time. When the weight reaches a certain limit, no more flapping is done, thus suppressing the route.

See also

[edit]- Exponential formula

- Exponential growth

- Radioactive decay for the mathematics of chains of exponential processes with differing constants

Notes

[edit]- ^ Serway, Moses & Moyer (1989, p. 384)

- ^ Simmons (1972, p. 15)

- ^ McGraw-Hill (2007)

- ^ Leike, A. (2002). "Demonstration of the exponential decay law using beer froth". European Journal of Physics. 23 (1): 21–26. Bibcode:2002EJPh...23...21L. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.5948. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/23/1/304. S2CID 250873501.

References

[edit]- McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 2007. ISBN 978-0-07-144143-8.

- Serway, Raymond A.; Moses, Clement J.; Moyer, Curt A. (1989), Modern Physics, Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 0-03-004844-3

- Simmons, George F. (1972), Differential Equations with Applications and Historical Notes, New York: McGraw-Hill, LCCN 75173716

External links

[edit]Exponential decay

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Exponential decay describes a process in which a quantity undergoes a continuous decrease over time at a rate that is directly proportional to its current value. This proportionality implies that the larger the quantity, the faster it diminishes in absolute terms, but the rate of decline slows as the quantity decreases, leading to a characteristic curve that approaches zero asymptotically.[8] The negative rate of change distinguishes decay from growth, with the constant of proportionality—known as the decay constant—determining the rapidity of the process. This fundamental behavior arises in various natural phenomena where interactions or losses occur independently for each unit of the quantity.[9] Historically, the exponential law was first rigorously applied in physics to radioactive decay by Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy around 1902, who observed that the rate of atomic disintegration in thorium compounds was proportional to the number of undecayed atoms present.[10] Earlier conceptual foundations appeared in studies of compound interest and population dynamics in the late 17th century, but physical formalization occurred with radioactivity.[11] Intuitive illustrations include the cooling of a hot object placed in a cooler surroundings, where the heat loss rate is proportional to the temperature difference, causing the object's temperature to approach the ambient level exponentially. Similarly, in a biological population with no births, if deaths occur at a rate proportional to the existing population, the size diminishes exponentially over time.[9]Basic Mathematical Model

The basic mathematical model for exponential decay is described by the equation where denotes the quantity of the decaying substance at time , is the initial quantity at , and is the decay constant.[2] This model assumes that the rate of decay is directly proportional to the current amount present, leading to a continuous decrease over time.[4] The form was originally developed in the study of radioactive processes by Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy, who observed that the amount of active material diminishes geometrically with time.[12] The decay constant quantifies the fractional rate at which the quantity decays per unit time, such that in a small time interval , the fraction lost is approximately .[4] Its units are inverse time, such as per second (s) or per year (yr), ensuring the exponent remains dimensionless as required for the exponential function.[1] Graphically, traces a smooth, decreasing curve starting at when and approaching the horizontal axis asymptotically as increases, with a concave-up shape due to the second derivative being positive.[1] The initial slope of the curve at is , reflecting the maximum rate of decay at the outset.[2] This model connects to the underlying proportional rate via the differential equation .[2]Time Scales and Measurements

Half-Life

In exponential decay, the half-life, denoted , is defined as the time required for the quantity of a decaying substance to reduce to half its initial value.[13][14] This characteristic time is related to the decay constant by the formula where is the natural logarithm of 2, approximately 0.693.[13][15] A key property of the half-life is its constancy for a given decay process, independent of the initial quantity ; after exactly half-lives, the remaining quantity is .[13][5] For example, if the decay constant per year, then years.[13] The half-life offers an intuitive measure for non-experts, as it directly conveys the time scale in familiar terms of halving, unlike the abstract decay constant .[1] The half-life relates to the mean lifetime (another time scale in exponential decay) by .[15]Mean Lifetime

The mean lifetime, denoted as , represents the expected time an individual decaying entity persists before undergoing decay in an exponential process, calculated as , where is the decay constant.[16] This statistical average arises from the inherent randomness of decay events, providing a measure of the typical persistence time for a single unit, such as a radioactive nucleus or unstable particle.[16] In probabilistic terms, particularly for radioactive decay, the survival probability—the fraction of entities remaining undecayed at time —is given by .[16] This exponential form reflects the memoryless property of the process, where the likelihood of decay remains constant regardless of elapsed time. The mean lifetime relates to the total expected events through the integral of this survival probability over all time: which evaluates directly to , confirming its role as the average persistence duration.[16] The mean lifetime exceeds the half-life , the time for half the population to decay, by a factor of approximately $1.443\tau \approx 1.443 , t_{1/2}\lambda = 0.05 , \mathrm{s}^{-1}\tau = 20$ seconds.[16]Advanced Formulations

Derivation from Differential Equations

The mathematical foundation of exponential decay is derived from the first-order ordinary differential equation that posits the instantaneous rate of change of a quantity is proportional to its current value, with the proportionality constant being negative to indicate decay. This model captures processes where the likelihood of decrease at any moment depends solely on the present amount, such as in certain physical or biological systems under idealized conditions. The governing equation is where represents the quantity at time , and is the constant decay rate, ensuring the rate of decrease is directly proportional to . This formulation assumes the decay process occurs continuously in time and that remains fixed, unaffected by external influences or time variations. To solve this separable differential equation, rearrange by dividing both sides by (assuming ): which separates the variables as Integrating both sides with respect to their respective variables gives yielding where is the constant of integration. Exponentiating both sides produces Defining the initial quantity (satisfying the initial condition at ), the general solution simplifies to This explicit form requires only basic calculus knowledge of integration and separation of variables for separable first-order differential equations.[2] Verification confirms the solution's validity: differentiating yields which matches the original differential equation exactly. The derivation further presupposes a Markovian (memoryless) process, where the system's future evolution depends only on the current state , without regard to prior history—a property inherent to the exponential form in continuous-time models.[15][17] This solution underpins derived quantities such as the half-life , the time required for to halve.[1]Multiple Decay Processes

In cases where a decaying species can undergo transformation through multiple independent pathways simultaneously, known as parallel decay processes, the overall dynamics remain governed by exponential decay, but with an effective total decay constant that is the sum of the individual partial decay constants for each channel.[18] Specifically, if the partial decay constants are , the total decay constant is . This summation arises under the assumption that the processes are independent, with no interference or correlation between the channels, allowing the probabilities to add linearly.[18] The probability that a decay event proceeds through a specific pathway is given by the branching ratio, defined as , which represents the fraction of decays occurring via that mode relative to all possible channels./01:_Introduction_to_Nuclear_Physics/1.03:_Radioactive_decay) These ratios are typically determined experimentally and sum to unity across all pathways. The number of undecayed parent nuclei still follows the exponential form , ensuring the overall depletion rate is faster than for any single channel alone.[18] However, the production rate of each daughter product from pathway is , leading to distinct exponential buildup curves for each product, scaled by their respective branching ratios. A prominent example occurs in radioactive isotopes capable of both alpha and beta decay, such as bismuth-212 (), which decays via beta emission to polonium-212 with a branching ratio of 64.06% and via alpha emission to thallium-208 with a branching ratio of 35.94%.[19] These measured fractions reflect the relative partial rates, with the total half-life of (approximately 60.55 minutes) determined by the summed , influencing applications in nuclear medicine and decay chain modeling.[19]Sequential Decay Chains

In sequential decay chains, also known as decay series, a radioactive parent nuclide decays into a daughter nuclide, which in turn decays into a subsequent nuclide, forming a linear sequence of transformations. This process is modeled by a system of coupled first-order differential equations that describe the time evolution of the number of atoms in each species. For a simple two-step chain where nuclide 1 decays to nuclide 2, which then decays further, the governing equations are: where and are the number of atoms of the parent and daughter, respectively, and are their respective decay constants, and initial conditions are with . These equations, known as the Bateman equations, were first derived to solve such radioactive transformation problems.[20] The analytical solution for the parent nuclide is straightforward, following the standard exponential decay form: For the daughter nuclide, assuming , the solution is: This expression shows that initially increases as atoms accumulate from the parent's decay, reaches a maximum, and then decreases as the daughter decays on its own timescale. The Bateman equations can be extended to longer chains by adding more coupled equations for subsequent nuclides.[20] A key concept in such chains is secular equilibrium, which arises when the parent's half-life is much longer than that of the daughter (). In this limit, after sufficient time, the production rate of the daughter equals its decay rate, leading to a constant ratio of their activities: . The parent's population decreases negligibly over the observation period, maintaining steady-state conditions for the daughter. An illustrative example is the uranium-238 decay series, which undergoes 14 successive alpha and beta decays through intermediate nuclides such as thorium-234, protactinium-234, and radium-226, ultimately terminating at the stable lead-206. This chain exemplifies how Bateman equations apply to multi-step processes, with secular equilibrium often holding between long-lived parents like uranium-238 (half-life 4.47 billion years) and shorter-lived daughters./21%3A_Nuclear_Chemistry/21.03%3A_Radioactive_Decay) For longer chains, direct analytical solutions become cumbersome, so matrix methods are employed to solve the system of differential equations. The decay chain is represented as , where is the vector of atom numbers and is the decay matrix with off-diagonal elements for production and diagonal . The solution is , computed via matrix exponentiation or eigenvalue decomposition for numerical efficiency. This algebraic approach simplifies handling arbitrary chain lengths and is extensible to cases with minor branching.Applications

Physical and Chemical Systems

In physical systems, exponential decay manifests prominently in radioactive decay, where unstable atomic nuclei spontaneously disintegrate, emitting particles or radiation at a rate governed by a decay constant λ that arises from nuclear instability.[21] The number of undecayed nuclei decreases exponentially as N(t) = N₀ e^{-λt}, with λ determined experimentally by observing decay rates over time using detectors such as Geiger counters.[22] A key application is carbon-14 dating, which relies on the beta decay of ^{14}C to ^{14}N with a half-life of 5730 years, allowing archaeologists to estimate the age of organic materials up to about 50,000 years old by measuring residual ^{14}C levels.[23] In chemical systems, exponential decay describes first-order reactions, where the rate depends solely on the concentration of a single reactant, as in unimolecular decompositions.[24] The concentration [A] evolves as A = [A]_0 e^{-kt}, with rate constant k reflecting molecular collision frequencies and activation energies. A classic example is the gas-phase decomposition of dinitrogen pentoxide, 2N₂O₅ → 4NO₂ + O₂, which follows first-order kinetics with k ≈ 6.82 × 10^{-3} s^{-1} at 70°C,[25] enabling predictions of reaction progress in atmospheric chemistry and industrial processes.[24] Exponential decay also governs the discharge of a capacitor in an RC circuit, where stored charge dissipates through a resistor, leading to a voltage drop V(t) = V₀ e^{-t/τ} with time constant τ = RC.[26] This behavior, observable in oscilloscope traces, underscores the role of exponential processes in electronics, such as timing circuits and signal filtering. Newton's law of cooling approximates exponential decay for the temperature T(t) of an object cooling in a surrounding medium at T_s, where dT/dt ∝ (T - T_s), yielding T(t) - T_s = (T₀ - T_s) e^{-kt} for small temperature differences that neglect nonlinear heat transfer effects.[27] This model applies to scenarios like cooling hot metals in metallurgy or environmental heat loss studies. In nuclear physics, quantum tunneling explains alpha decay as an exponential process, where an alpha particle escapes the Coulomb barrier of the nucleus despite insufficient classical energy, with decay probability following Gamow's 1928 theory that predicts observed half-lives through barrier penetration integrals.[28]Biological and Medical Contexts

In pharmacokinetics, the elimination of many drugs from the body follows first-order kinetics, where the rate of decay is proportional to the drug concentration, leading to an exponential decline over time. This process is characterized by the drug's half-life, which determines dosing intervals to maintain therapeutic levels; for example, aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) has a plasma half-life of approximately 15-20 minutes before rapid hydrolysis to salicylic acid.[29][30] Radioactive tracers exploit exponential decay for medical imaging and therapy, as their short half-lives allow targeted delivery with minimal long-term radiation exposure. Iodine-131, with a half-life of about 8 days, is commonly used in thyroid treatment and diagnostics, where it accumulates in thyroid tissue and decays via beta emission to destroy overactive cells or image function.[31] In positron emission tomography (PET) scans, fluorine-18-labeled tracers, such as fluorodeoxyglucose, have a half-life of 109.8 minutes, enabling real-time visualization of metabolic activity in tissues like tumors or the brain before significant decay occurs.[32][33] In epidemiology, exponential decay approximates the decline of infectious cases in untreated populations during the recovery phase of outbreaks, as modeled by the susceptible-infectious-recovered (SIR) framework. When the susceptible population is largely depleted, the rate of new infections drops, and the infected compartment decreases exponentially at a rate governed by the recovery parameter, reflecting natural immunity or resolution without intervention.[34] Enzyme kinetics often follows the Michaelis-Menten model, where substrate decay exhibits exponential behavior at low concentrations, approximating first-order kinetics. In this regime, the reaction velocity is linearly proportional to substrate concentration ([S] << K_m), such that the substrate depletes as S = [S]0 e^{-(V{\max}/K_m) t}, emphasizing the enzyme's high affinity and efficient turnover for scarce substrates in biological systems.[35][36]Economic and Social Models

In economics, exponential decay models asset depreciation to reflect the rapid loss of value in early years, contrasting with straight-line methods that assume uniform decline. The double-declining balance (DDB) method, an accelerated depreciation technique, applies twice the straight-line rate to the asset's declining book value annually, resulting in exponential decay of the asset's recorded value over time. For instance, under U.S. tax rules, machinery with a five-year useful life and $10,000 cost (ignoring salvage) depreciates at 40% of the current book value each year, yielding deductions of $4,000 in year 1, $2,400 in year 2, and so on, until switching to straight-line for remaining value. This approach aligns with economic reality for assets like equipment, where obsolescence accelerates value loss, and is prescribed in IRS guidelines for Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) property classes.[37] In social sciences, exponential decay underpins models of learning and forgetting, notably Hermann Ebbinghaus's 1885 experiments on memory retention using nonsense syllables. Ebbinghaus observed that retention drops sharply initially and then flattens, fitting an exponential curve where the proportion retained after time is given by , with representing the relative strength of the initial memory. This "forgetting curve" quantifies how, without reinforcement, up to 90% of new information may be lost within a week, influencing educational strategies like spaced repetition to counteract decay. Modern replications confirm the exponential nature, with half-life metrics varying by material strength but consistently showing rapid early decline.[38][39] Exponential decay also appears in market diffusion models for technology adoption, where growth follows an S-curve but post-peak sales decline exponentially toward saturation. Frank Bass's 1969 model describes cumulative adoption , where is the innovation coefficient (external influence) and the imitation coefficient (internal influence), implying the non-adopted market fraction decays at an effective rate influenced by . For consumer durables like color televisions, this captured peak adoption in the 1960s followed by decay as market penetration exceeded 90%, aiding forecasts for innovations like smartphones. Extensions apply to post-peak decay in technology lifecycles, where adoption rates halve roughly every fixed interval after inflection. In macroeconomic contexts, hyperinflation erodes purchasing power through exponential decay, as modeled by Philip Cagan in 1956. Cagan's framework posits money demand , where is real balances, expected inflation, leading to explosive price growth when seigniorage exceeds demand elasticity, halving currency value monthly in episodes like 1920s Germany. This results in real purchasing power decaying exponentially, with adaptive expectations amplifying the rate until stabilization. Empirical analysis of seven hyperinflations showed inflation accelerating geometrically until policy intervention, underscoring exponential dynamics in currency devaluation.[40] Social network analysis employs exponential decay to model user churn, capturing dropout rates that diminish over time as engagement builds loyalty. In platforms like Weibo, churn hazard follows , where induces exponential-like decay in probability for long-term users, with social ties reducing attrition by up to 30% via mixture effects. Studies on millions of users reveal initial high churn (e.g., 20% monthly for new accounts) decaying to steady-state rates below 5%, driven by network density; for example, core users with strong links exhibit half-lives exceeding 500 days. This informs retention strategies, prioritizing interventions for at-risk peripherals.[41]Computational and Engineering Uses

In computational contexts, exponential decay manifests in numerical stability challenges, particularly underflow in floating-point arithmetic, where repeated multiplications by factors less than 1 in algorithms simulating decay processes can produce values smaller than the smallest representable number, leading to abrupt transitions to zero and loss of precision. This issue is prominent when evaluating functions like for large , as the exponentiation may underflow the denormalized range in IEEE 754 standards.[42] In machine learning algorithms, exponential decay is employed in learning rate schedulers for gradient descent optimization, where the initial learning rate is multiplied by a decay factor at each epoch, yielding , to stabilize training by reducing step sizes over time and improving convergence in deep neural networks. PyTorch'sExponentialLR scheduler implements this directly, allowing practitioners to set (typically 0.9–0.99) for parameter groups in optimizers like Adam or SGD.

Signal processing leverages exponential decay in first-order low-pass filters, whose impulse response is for , where is the time constant determining the filter's cutoff frequency and the rate of signal smoothing to attenuate high-frequency noise. Digital implementations, such as the infinite impulse response (IIR) filter with , approximate this continuous behavior in discrete-time systems like audio processing or sensor data filtering.[43]

In reliability engineering, the exponential distribution models constant failure rates , where the hazard function implies survival probability , serving as a baseline for systems with memoryless failures, such as electronic components under random stress. This corresponds to the Weibull distribution with shape parameter , enabling mean time to failure (MTTF) calculations as for predicting system uptime in design and maintenance.[44]

Exponential decay also governs the envelope of damped oscillations in engineering systems, such as RLC circuits where the underdamped voltage response is with damping factor , or in mechanical vibrations where for mass-spring-damper setups, ensuring controlled energy dissipation to prevent resonance failures.[45]