Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

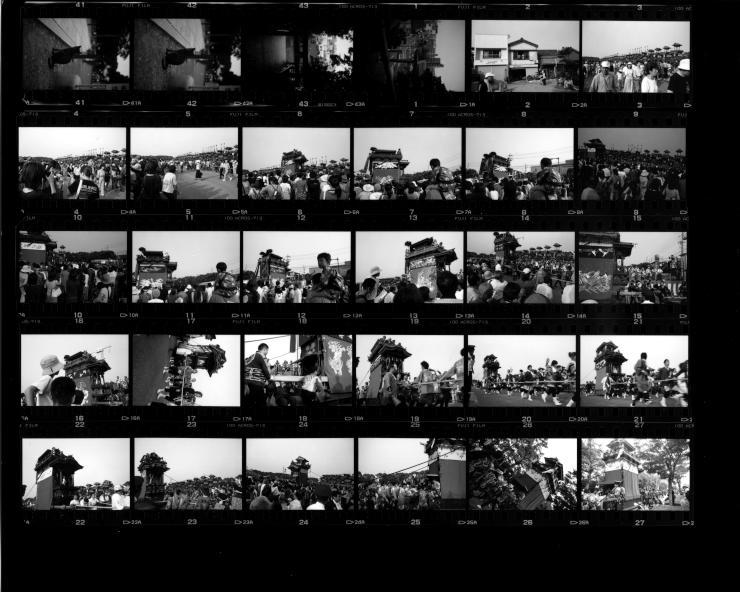

Contact print

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

A contact print is a photographic image produced from film; sometimes from a film negative, and sometimes from a film positive or paper negative.[1] In a darkroom an exposed and developed piece of film or photographic paper is placed emulsion side down, in contact with a piece of photographic paper, light is briefly shone through the negative or paper and then the paper is developed to reveal the final print.[2]

The defining characteristic of a contact print is that the resulting print is the same size as the original, rather than having been projected through an enlarger.

Basic tools

[edit]

Contact printing is a simple and inexpensive process. Its simplicity avails itself to those who may want to try darkroom processing without buying an enlarger. One or more negatives are placed on a sheet of photographic paper which is briefly exposed to a light source. The light may come from a low wattage frosted bulb hanging above an easel which holds them together, or contained in an exposure box with a plate of frosted glass on top. Accurate timing of the light comes with experience, but only a little experimenting leads to positive results. The negative and the photographic paper are placed on the glass plate of the exposure box. A hinged top-cover presses the negatives in close contact with the paper and keeps them in place. The paper is then developed and the result is called a contact print. After exposure, the paper is processed using chemicals in the darkroom to produce the final print. The paper must be placed in a developer bath, a stop bath, fixer, and finally the hypo-eliminator bath, in that order. Failure to adhere precisely to this process will result in a poor-quality final image with a variety of issues.[3]

Ansel Adams describes procedures for making contact prints using ordinary lighting in his book, The Print.

Proof sheets

[edit]Since this process produces neither enlargements nor reductions, the image on the print is exactly the same size as the image on the negative. Contact prints are used to produce proof sheets from entire rolls of 35 mm negative (from 135 film cassettes) and 120 (21⁄4 film rolls) in order to aid in the selection of images for further enlargement, and for cataloging and identification purposes. For 120 roll film (once a common negative size for popular cameras) and larger film, contact prints are often used to determine the final print size. In medium and large format photography, contact prints are prized for their extreme fidelity to the negative, with exquisite detail that can be seen with the use of a magnifying glass. A disadvantage to using contact prints in the fine-arts is the laboriousness of modifying exposure selectively, when the use of an enlarger can achieve the same purpose.

Because light does not pass any significant distance through the air or through lenses in going from the negative to the print, the contact process ideally preserves all the detail that is present in the negative. However, the exposure value (EV) range, the variation from darkest to lightest regions, is inherently greater in negatives than in prints.

Finished prints

[edit]When large format film is contact printed to create finished work, it is possible, but not easy, to use local controls to interpret the image on the negative. "Burning" and "dodging" (either increasing the amount of light that one area of the print receives, or decreasing the amount of light in order to achieve the ideal tonal range in a particular area) require painstaking work with photographic masks, or the use of a production contact printing machine (Arkay, Morse, Burke and James are manufacturers who make contact printing machines).

Some alternative processes or non-silver processes, such as van Dyke and cyanotype printing, must be contact printed. Medium or large format negatives are almost always used for these types of printing. Images from smaller formats may be transferred to a larger format negative for this purpose.

Production tools

[edit]Contact printing machines are more elaborate devices than the more familiar and widely available contact printing frames. They typically combine in a box the light source, intermediate glass stages, and a final glass stage for the negative and paper to be placed upon, as well as an elastic pressure plate to keep the negative and the paper in tight contact. Dodging can be accomplished by placing fine tissue paper on the intermediate glass stages between the light source and the negative/paper sandwich to modify the exposure locally. The benefit to such time intensive techniques is the ability to then make multiple prints with negligible variation, at full production speed.

Other uses for the technique

[edit]Contact printing was also once used in photolithography, and in printed circuit manufacturing.

Motion picture prints are often contact printed either from an original, or a duplicate negative.

The contact exposure process usually refers to a film negative used in conjunction with printing paper, but the process may be used with any transparent or translucent original image printed by contact onto a light sensitive material. Negatives or positives on film or even paper may for various purposes be used to make contact exposures onto different films and papers. Intermediary products such as internegatives, interpositives, enlarged negatives, and contrast controlling masks are often made using contact exposures.

Computer screens and other electronic display devices provide an alternative approach to contact printing. A permanent image (negative, positive film or transparency, or translucent original) is not used, instead the light sensitive material is exposed directly to the display device in a dark room for a controllable duration.[4] The resulting image generated by this mixed digital/analogue technique has been coined "laptopogram". While limited by the image display device resolution, which can be much inferior to film negatives, the widespread use of electronic displays provides great potential to this unorthodox contact printing method.

In contact sheet photography, the traditional contact sheet is used as a way to make pictures consisting of partial photos. The resulting image spans the whole sheet, divided into squares by the black borders of the film.[5]

Artistic and practical considerations

[edit]Photographers praise the beautiful intermediate gray or color gradation that results from making prints this way. Each print is necessarily the same size as the corresponding image on the negative. This makes contact prints from large-format negatives, especially 5×7 inch and larger, most usable for fine-art work. Smaller contact prints, from films and formats such as 135 film cassettes, 35 mm (24×36 mm images), and 120/220 roll film (6 cm), are useful for evaluation of exposure, composition, and subject.

It is cheaper and easier to avoid making conventional prints of all the exposures with an enlarger; the photographer prints only the best negatives. Selection is usually made using a loupe — a special magnifying glass with a transparent base — to examine the tiny prints, still aligned as they are on the negative strips. Negatives themselves can be examined with a loupe, but blacks and whites are the reverse of what is seen through the view finder (hence: a negative), which makes it more difficult to interpret the images. Contact sheets can easily be stored in files in the dark, along with the negatives.

Notable photographers

[edit]Edward Weston made most of his pictures using contact print technique.[6]

See also

[edit]- Analog photography

- Projector for a directory of projector types

- Paper negative

- Photogram

- Thumbnail a digital cognate of the contact print

References

[edit]- ^ "Contact Print - National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 2025-06-22.

- ^ "Making a Black & White Print – Contact Sheets". Ilford Photo. 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2025-06-22.

- ^ www.photogs.com

- ^ makeprojects.com

- ^ Barnes, Sara (20 April 2018). "Photographer Transforms Everyday Subjects Into Fractured Versions of Themselves". www.mymodernmet.com. My Modern Met. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Edward Weston's Iconic Portrait Photography Using The Graflex Camera". Weston Photography: Four Generations of Photographic Excellence. 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2023-06-26.

External links

[edit] Media related to Contact prints at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Contact prints at Wikimedia Commons