Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Core electron

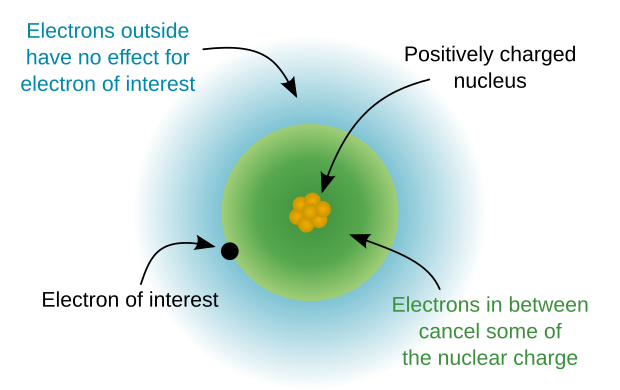

View on WikipediaCore electrons are the electrons in an atom that are not valence electrons and do not participate as directly in chemical bonding.[1] The nucleus and the core electrons of an atom form the atomic core. Core electrons are tightly bound to the nucleus. Therefore, unlike valence electrons, core electrons play a secondary role in chemical bonding and reactions by screening the positive charge of the atomic nucleus from the valence electrons.[2]

The number of valence electrons of an element can be determined by the periodic table group of the element (see valence electron):

- For main-group elements, the number of valence electrons ranges from 1 to 8 (ns and np orbitals).

- For transition metals, the number of valence electrons ranges from 3 to 12 (ns and (n−1)d orbitals).

- For lanthanides and actinides, the number of valence electrons ranges from 3 to 16 (ns, (n−2)f and (n−1)d orbitals).

All other non-valence electrons for an atom of that element are considered core electrons.

Orbital theory

[edit]A more complex explanation of the difference between core and valence electrons can be described with atomic orbital theory.[citation needed]

In atoms with a single electron the energy of an orbital is determined exclusively by the principal quantum number n. The n = 1 orbital has the lowest possible energy in the atom. For large n, the energy increases so much that the electron can easily escape from the atom. In single electron atoms, all energy levels with the same principle quantum number are degenerate, and have the same energy.[citation needed]

In atoms with more than one electron, the energy of an electron depends not only on the properties of the orbital it resides in, but also on its interactions with the other electrons in other orbitals. This requires consideration of the ℓ quantum number. Higher values of ℓ are associated with higher values of energy; for instance, the 2p state is higher than the 2s state. When ℓ = 2, the increase in energy of the orbital becomes large enough to push the energy of orbital above the energy of the s-orbital in the next higher shell; when ℓ = 3 the energy is pushed into the shell two steps higher. The filling of the 3d orbitals does not occur until the 4s orbitals have been filled.[citation needed]

The increase in energy for subshells of increasing angular momentum in larger atoms is due to electron–electron interaction effects, and it is specifically related to the ability of low angular momentum electrons to penetrate more effectively toward the nucleus, where they are subject to less screening from the charge of intervening electrons. Thus, in atoms of higher atomic number, the ℓ of electrons becomes more and more of a determining factor in their energy, and the principal quantum numbers n of electrons becomes less and less important in their energy placement. The energy sequence of the first 35 subshells (e.g., 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, etc.) is given in the following table [not shown?]. Each cell represents a subshell with n and ℓ given by its row and column indices, respectively. The number in the cell is the subshell's position in the sequence. See the periodic table below, organized by subshells. [citation needed]

Atomic core

[edit]The atomic core refers to the central part of the atom excluding the valence electrons.[3] The atomic core has a positive electric charge called the core charge and is the effective nuclear charge experienced by an outer shell electron. In other words, core charge is an expression of the attractive force experienced by the valence electrons to the core of an atom which takes into account the shielding effect of core electrons. Core charge can be calculated by taking the number of protons in the nucleus minus the number of core electrons, also called inner shell electrons, and is always a positive value in neutral atoms.

The mass of the core is almost equal to the mass of the atom. The atomic core can be considered spherically symmetric with sufficient accuracy. The core radius is at least three times smaller than the radius of the corresponding atom (if we calculate the radii by the same methods). For heavy atoms, the core radius grows slightly with increasing number of electrons. The radius of the core of the heaviest naturally occurring element - uranium - is comparable to the radius of a lithium atom, although the latter has only three electrons.

Chemical methods cannot separate the electrons of the core from the atom. When ionized by flame or ultraviolet radiation, atomic cores, as a rule, also remain intact.

Core charge is a convenient way of explaining trends in the periodic table.[4] Since the core charge increases as you move across a row of the periodic table, the outer-shell electrons are pulled more and more strongly towards the nucleus and the atomic radius decreases. This can be used to explain a number of periodic trends such as atomic radius, first ionization energy (IE), electronegativity, and oxidizing.

Core charge can also be calculated as 'atomic number' minus 'all electrons except those in the outer shell'. For example, chlorine (element 17), with electron configuration 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p5, has 17 protons and 10 inner shell electrons (2 in the first shell, and 8 in the second) so:

- Core charge = 17 − 10 = +7

A core charge is the net charge of a nucleus, considering the completed shells of electrons to act as a 'shield.' As a core charge increases, the valence electrons are more strongly attracted to the nucleus, and the atomic radius decreases across the period.

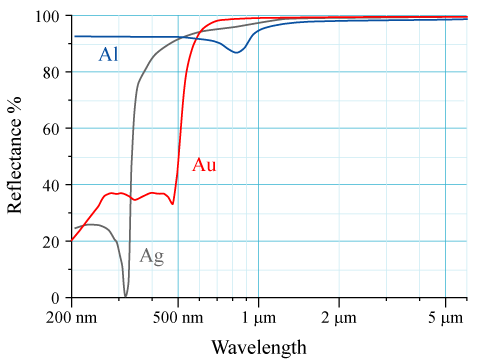

Relativistic effects

[edit]For elements with high atomic number Z, relativistic effects can be observed for core electrons. The velocities of core s electrons reach relativistic momentum which leads to contraction of 6s orbitals relative to 5d orbitals. Physical properties affected by these relativistic effects include lowered melting temperature of mercury and the observed golden colour of gold and caesium due to narrowing of energy gap.[5] Gold appears yellow because it absorbs blue light more than it absorbs other visible wavelengths of light and so reflects back yellow-toned light.

Electron transition

[edit]A core electron can be removed from its core-level upon absorption of electromagnetic radiation. This will either excite the electron to an empty valence shell or cause it to be emitted as a photoelectron due to the photoelectric effect. The resulting atom will have an empty space in the core electron shell, often referred to as a core-hole. It is in a metastable state and will decay within 10−15 s, releasing the excess energy via X-ray fluorescence (as a characteristic X-ray) or by the Auger effect.[6] Detection of the energy emitted by a valence electron falling into a lower-energy orbital provides useful information on the electronic and local lattice structures of a material. Although most of the time this energy is released in the form of a photon, the energy can also be transferred to another electron, which is ejected from the atom. This second ejected electron is called an Auger electron and this process of electronic transition with indirect radiation emission is known as the Auger effect.[7]

Every atom except hydrogen has core-level electrons with well-defined binding energies. It is therefore possible to select an element to probe by tuning the X-ray energy to the appropriate absorption edge. The spectra of the radiation emitted can be used to determine the elemental composition of a material.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rassolov, Vitaly A.; Pople, John A.; Redfern, Paul C.; Curtiss, Larry A. (2001-12-28). "The definition of core electrons". Chemical Physics Letters. 350 (5–6): 573–576. Bibcode:2001CPL...350..573R. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(01)01345-8.

- ^ Miessler, G. L. (1999). Inorganic Chemistry. Prentice Hall.

- ^ Harald Ibach, Hans Lüth. Solid-State Physics: An Introduction to Principles of Materials Science. Springer Science & Business Media, 2009. P.135

- ^ Spencer, James; Bodner, George M.; Rickard, Lyman H. (2012). Chemistry : structure and dynamics (5th ed.). Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-470-58711-9.

- ^ "Quantum Primer". www.chem1.com. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "auger effect". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00520

- ^ "The Auger Effect and Other Radiationless Transitions". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2015-12-11.